For the Poor and Disenfranchised, Higher Hurdles to Transplants

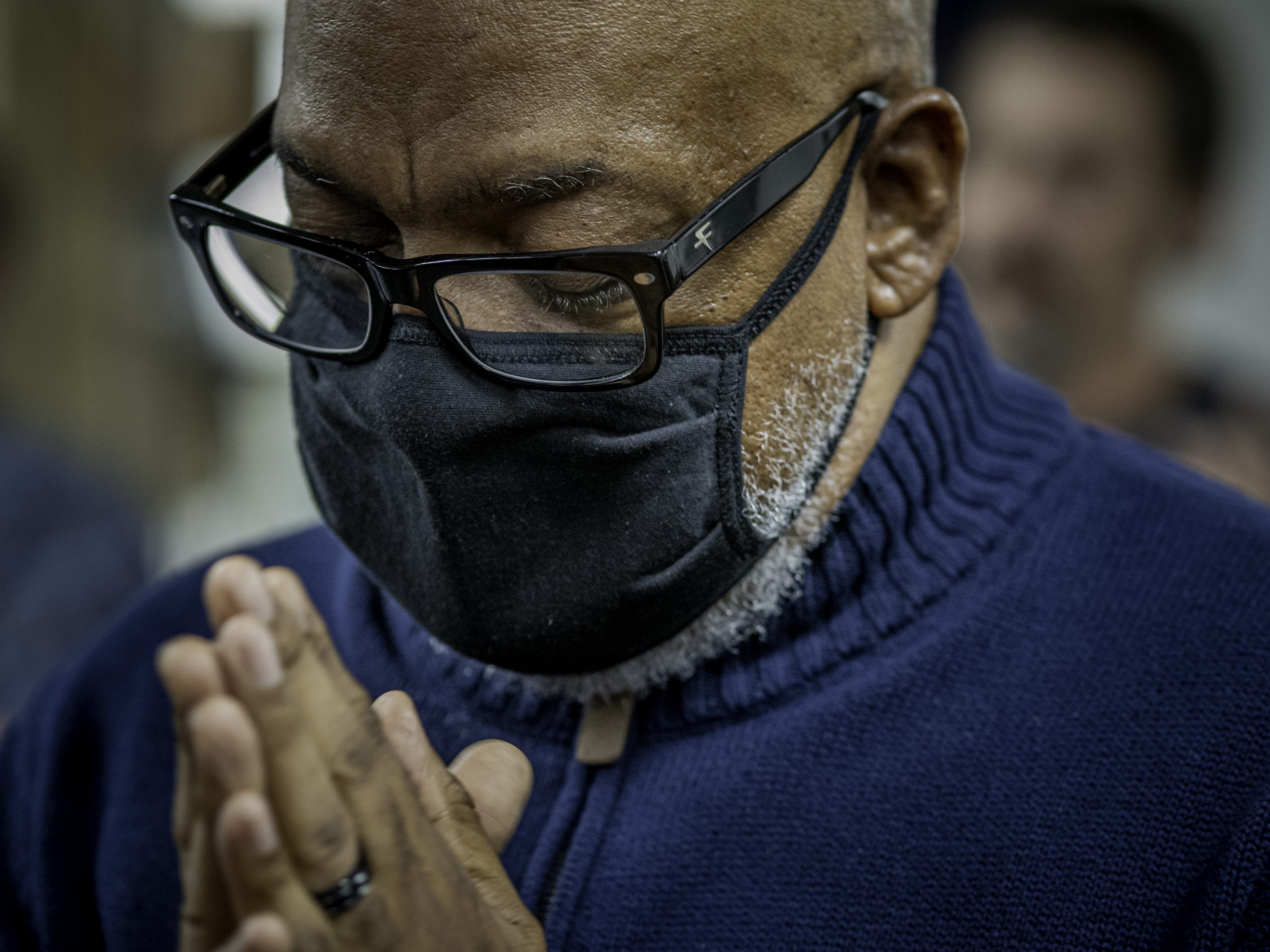

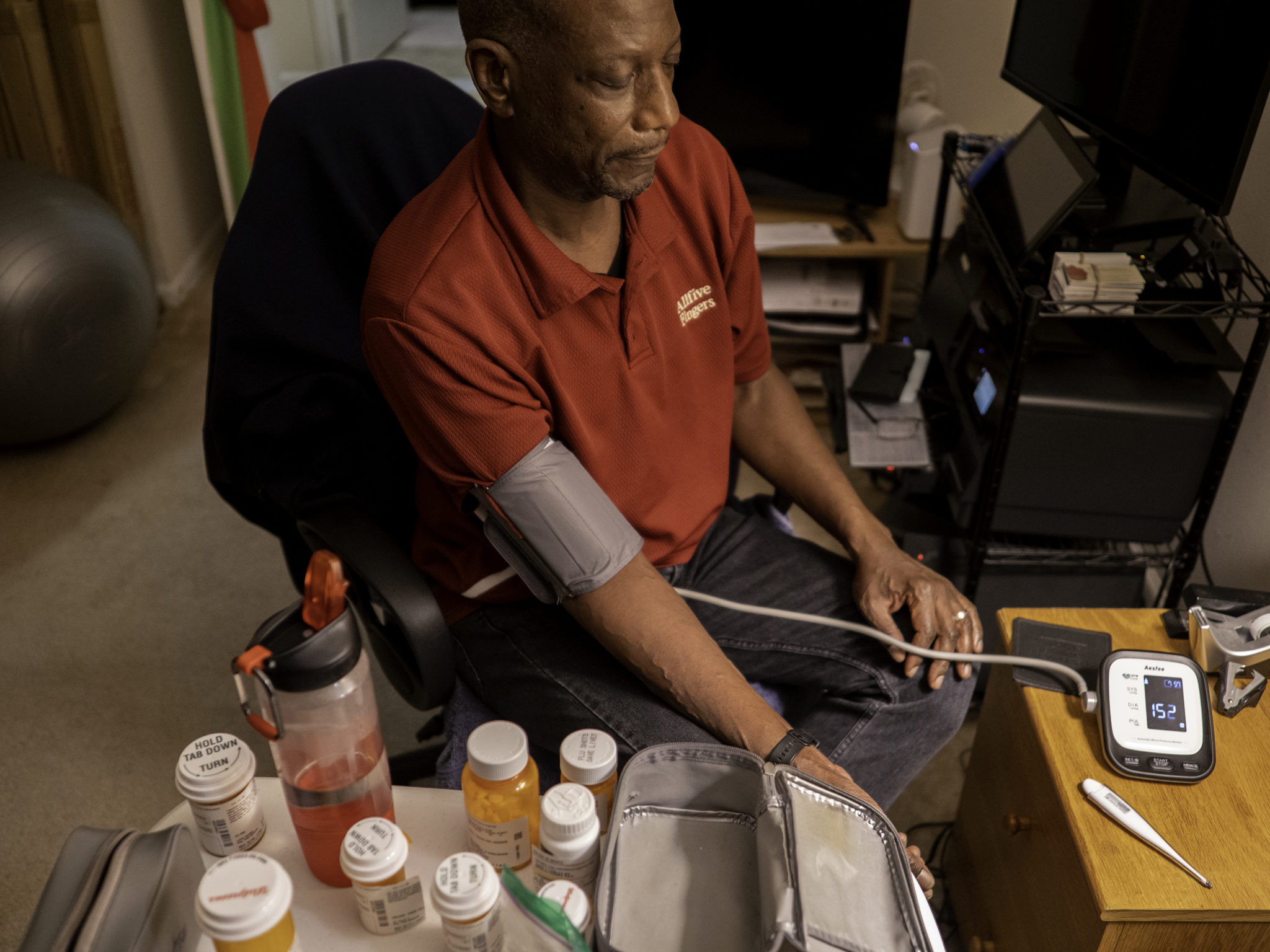

David White was first evaluated for a kidney transplant in 2011, but it would be four years before he got the call that his turn had come. In between undergoing various forms of dialysis to do the job his kidneys couldn’t and attending medical appointments to ensure he was healthy enough to survive the four-to-six-hour surgery, White busied himself with reading, exercise, and even trying to learn a new language to keep his mind off the fact that his kidneys were failing.

During his initial evaluations, the then 49-year-old consulted with social workers and completed a test to measure his heart function. Although White’s high blood pressure and kidney failure had taken a toll on his health, he says he sailed through the physical health checks with ease.

PROFIT & LOSS: THE COMPLETE SERIES

Intro | The Market | The Conflicts | The Disparities | The Waiting | The Alternatives

Even meeting with the financial planners at George Washington University Hospital seemed to go off without a hitch. Before the hospital would put White on the transplant list, they needed, among other things, to make sure that he would be able to afford the pricey anti-rejection medication that he would need for the rest of his life. And while it was true that it had always been a challenge for White and his wife to make ends meet — even before he went on disability following his kidney failure — the suburban D.C. couple had done the math and they were sure they could find a way to cover the transplant and associated medication.

Then, at a 2015 evaluation, his transplant team told him that he would also need to have some long overdue dental work completed before the hospital would add him to the kidney transplant list. The immunosuppressants used to ensure a successful transplant would leave him vulnerable to infections, and hidden pockets of bacteria in the mouth were a leading cause of problems. If White didn’t get the work done, the microbes in his mouth could proliferate and possibly kill him. But it was one hurdle too many, and White says he just couldn’t afford the procedure, which he estimates was between $1,500 and $2,000.

“I didn’t really have the financial means at the time,” he said.

The journey to that roadblock was a long one. White didn’t know his kidneys had failed until 2009, when weight loss and what he thought were cold symptoms eventually prompted his wife to insist he go to the emergency room. He was quickly transferred to the intensive care unit and would not leave the hospital for three weeks. He stopped producing urine several days after his arrival, and he wouldn’t urinate again for six years. During that stay in the hospital, he also began dialysis, and doctors told him he would have to continue to dialyze for the rest of his life — or until he got a transplant.

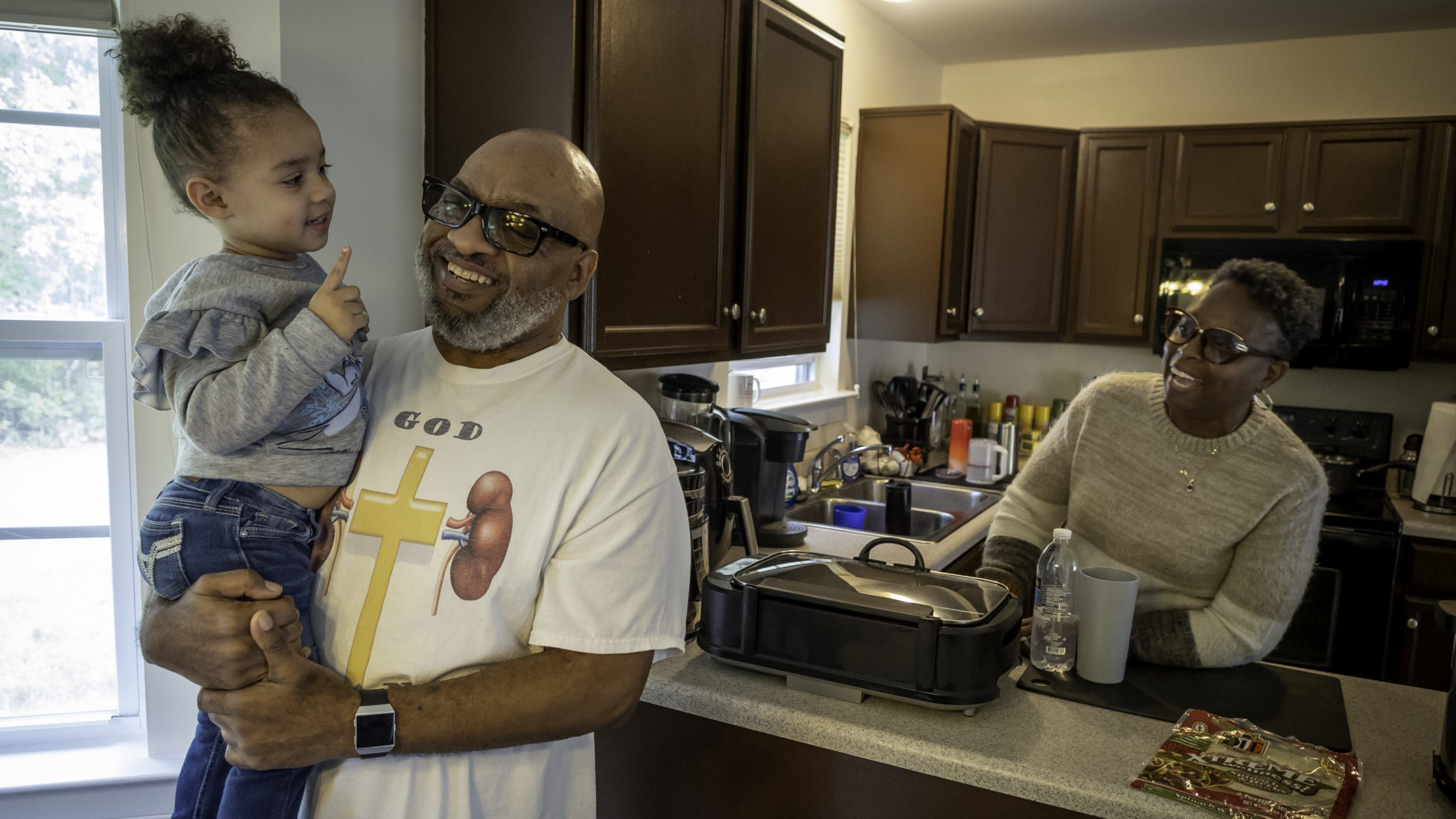

Making ends meet was hard even before David White’s kidneys failed, but he and his wife felt certain they could cover the costs of a transplant. Then he needed dental work.

After nearly six years on dialysis and finally getting so close to a new kidney, he was being stymied by a dental procedure. He didn’t have good credit at the time and even though he knew that some people with kidney disease had made ends meet with fundraisers and other forays for community support, it wasn’t something he was comfortable doing. And even if his own family wanted to help, White says, he wasn’t sure they’d be able to.

Organ transplants remain some of the most expensive medical procedures in the U.S. The international actuarial and consulting firm Milliman estimates that the average billable cost for a kidney transplant in 2020 is $442,500. If White didn’t have a so-called Medigap health insurance plan — a private insurance product meant to cover costs that other insurance plans don’t — he could have been on the hook for a substantial part of the cost. But even with top-notch insurance, transplant recipients may still have to cover what can be thousands of dollars in associated costs, including transportation, food, lodging, and lost wages. Then there’s the ongoing expense of anti-rejection medication, which Medicare only covers 80 percent of for the first three years post-transplant.

“If you didn’t have the money, you didn’t get on the waiting list,” said Clive Callender, a transplant surgeon who founded the Howard University Hospital Transplant Center in 1973.

The high price tag is one reason that low-income kidney failure patients, who are disproportionately Black or Hispanic, face a tougher path to transplants. Although organizations like the American Kidney Fund can help low-income families defray some of the costs of kidney disease and transplant care, and a 2014 policy change has reduced a longstanding bias in the allocation of deceased-donor kidneys to patients already on a waiting list, Black and Hispanic patients remain less likely to be referred for transplant in the first place, and they will have been on dialysis for far longer when they arrive on a waiting list. While they are four times more likely to experience kidney failure than White Americans, Black patients like White will also spend an average of 2.5 months longer waiting for a transplant, and their bodies are significantly more likely to reject their new kidney in the five years following transplant, according to a 2016 study in Kidney International, the journal of the International Society of Nephrology.

Indeed, racial and economic disparities permeate every aspect of kidney disease, from diagnosis to transplant outcomes. Poor and working class Americans, along with those from racial and ethnic minorities, are more likely to have diabetes and hypertension — the country’s two leading causes of kidney failure. They are less likely to see a nephrologist before starting dialysis, and they progress more quickly from kidney disease to renal failure.

The disparities also spill over into living-donor kidneys, whereby donors provide one of their two healthy kidneys to help an ailing family or community member. While national data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) shows that Black Americans are more likely to be deceased donors on a per capita basis than White Americans, barriers of cost, education, and higher rates of other medical issues in would-be living donors mean that Black kidney disease patients are far less likely to find such a compatible donor than their White counterparts — and a January 2018 analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that this gap is growing, too. According to the study, rates of living donor transplants among Black patients two years after getting on the waiting list dropped from 3.4 percent in 1995 to 2.9 percent in 2014. For White patients, they rose from 7 percent to 11.4 percent during this time.

Even some of the fundamental science that has traditionally informed modern diagnosis of kidney failure, some experts now say, is built on earlier, low-quality studies that made flawed assumptions about Black physiology. This means that even when under the care of competent doctors, a White patient may have higher odds of having an as-yet undiagnosed kidney problem discovered, and that they’ll be referred for treatment earlier in the course of their disease.

All of this means that, for minority patients like White, the kidney disease gauntlet — from diagnosis to dialysis, and from donation to transplant — is often filled with roadblocks that other patients, by dint of a higher income or, as many critics note, lighter skin, are less likely to face.

“Institutionalized racism is the elephant in the room that has not been addressed,” said Callender.

It is “an obstacle to everything that we do,” he added, “and we pay the price.”

The disparities in kidney failure start long before the pair of fist-sized organs have started to decline. In the U.S., the two conditions that contribute to more kidney disease than anything else are diabetes and hypertension. Both conditions can damage the tiny, delicate blood vessels in the kidney’s nearly 12 miles of glomeruli that filter waste from the blood. Over time, kidneys become less and less able to do their job. If the damage gets bad enough, the kidneys stop working completely.

Black Americans are 40 percent more likely to have hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, compared to White Americans, and are 60 percent more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes, according to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Those who identify as Hispanic or Latino are also 1.7 times as likely to have a diabetes diagnosis. Already, this places those with Black and Brown bodies at higher risk of developing kidney problems. Although scientists have found similar or even lower rates of early-stage kidney disease in Black patients compared to White patients, several studies have shown that Black Americans are more likely to progress to kidney failure, and that they do so more quickly than their White counterparts.

According to data from the 2018 U.S. Renal Data System annual report, the latest year for which detailed information is available, the prevalence of kidney failure was 3.7 times higher in Black Americans compared to White Americans.

Meera Harhay, a transplant nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia, says that many of her patients report they only learned of their kidney disease when they arrived at the emergency room and were told they urgently needed dialysis to survive. Up until a person is in overt kidney failure, the symptoms are often silent, according to information from the National Kidney Foundation. It’s why only 31.1 percent of those with kidney failure received 12 months of nephrologist treatment before they started dialysis, according to a data analysis published in JAMA Network Open in August. Both Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive this care compared to White patients.

“It’s really kind of a question of the haves and have nots,” Harhay said. “These disparities that exist in health and in society are kind of amplified in our disease course because so much hinges on early diagnosis and treatment, so you really kind of see when it goes right and when it goes wrong, and it’s starkly different.”

To Laura Plantinga, an epidemiologist at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, the racial disparities among patients waiting for transplant are obvious at many Atlanta-area dialysis clinics. “You walk in there and it’s very clear,” she said. “You rarely see White people, honestly.”

For professionals like herself, it’s not always easy to understand the sheer number of barriers they face. “We live in a different world from a lot of these patients,” Plantinga said.

The first steps towards a kidney transplant begin long before someone is wheeled into the operating room. For Patrick Gee, a former corrections officer, those steps began in flip-flops on his way into his nephrologist’s office. Unlike many whose kidneys fail, Gee wasn’t diagnosed in the emergency room. Instead, an appointment with his endocrinologist for diabetes management in April 2013 first alerted him that his kidneys were operating at about 35 percent of their normal function. The doctor referred Gee to a nephrologist, who recommended monitoring his kidney function and cutting out certain foods like dairy, nuts, and chocolate. “But eventually,” Gee recalled the nephrologist telling him, “you’re gonna be on dialysis.”

By November, Gee’s weight had ballooned to 378 pounds. When he walked into his nephrologist’s office with his wife Tina, the only clothes Gee could wear were his sandals, white socks, a pair of black sweatpants, and a white t-shirt.

“I didn’t have no shoes to wear, didn’t even have a coat big enough to fit me. It had gotten so bad that I couldn’t even lay down in my bed and sleep at night. I would have to sit up in a chair and sleep,” Gee said.

At the appointment, Gee’s wife asked the nephrologist about dialysis and the couple opted for an at-home treatment called peritoneal dialysis, which uses the lining of the abdomen and a cleaning fluid called dialysate to filter blood inside the body. Gee started dialysis in December 2013. There was no discussion of a transplant at that time; Gee didn’t get on the waiting list until February 2016.

Many patients are in such shock from having to start dialysis that they can’t begin to think about transplant, Plantinga says, but it’s up to the physicians to continue to bring up the topic. A preemptive transplant — done before a patient begins dialysis — can improve patient survival and their quality of life.

Because the government — via Medicare — pays for so much of kidney failure treatment, Mara McAdams-DeMarco, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says there’s a vested interest in figuring out which treatments work best for which patients, especially when many of them have other chronic diseases, too. “I see nephrology patients as really being the underdogs,” she said. “You don’t see the level of NIH support or public knowledge or public awareness relative to the burden of kidney disease in the United States.”

Indeed, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network recommends transplant referrals take place before stage 5 of chronic kidney disease (when the kidneys are severely compromised but have not yet failed, and so a person is not yet on dialysis) rather than when they begin dialysis. But a preemptive transplant requires that patients see a specialist before their kidneys have completely failed, which doesn’t happen for the 23 to 38 percent of patients who “crash” onto dialysis, with little to no prior care from a nephrologist. Those in this group, such as White, are overwhelmingly low-income minorities who are un- or under-insured. As a result, the 2.5 percent of end-stage renal disease patients treated with a preemptive transplant were significantly less likely to be Black or Hispanic, according to a study in the journal Transplantation.

Johns Hopkins epidemiologist Dr. Mara McAdams-DeMarco, photographed on a recent video call. McAdams-DeMarco says the government has an incentive to improve kidney failure treatments because Medicare often foots the bill.

According to Lilia Cervantes, an internal medicine hospitalist at Denver Health, in addition to potential language barriers, many low-income Hispanic patients are too pre-occupied with what they perceive as more pressing priorities — paying bills, making rent — that make it difficult for them to properly navigate themselves toward kidney transplant — even with the best of care. “Those are the things that you wake up thinking about and you go to bed thinking about,” Cervantes said. “And so they may not be able to sort of even consider anything outside of just having food on the table.” For many undocumented patients, the challenges can be even more insurmountable. Without access to health insurance, Cervantes said, these patients likely can’t “pay for the medications and surgery, [or] the follow-up appointments that are necessary for anyone to receive a kidney transplant.”

Harhay says that Black patients like Gee and White face an additional challenge in being diagnosed with kidney failure. The kidneys’ job is to filter waste from the blood through the blood vessels that make up the glomeruli. A person’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR) can’t easily be measured directly, but a blood test that measures creatinine — a compound which is produced by muscles during everyday activity and filtered by the kidneys — is often used as a proxy. In 1999, a team of experts from across the country sought to improve GFR estimates. The researchers used a group of 1,628 patients with chronic kidney disease who were part of a study called the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, which provided detailed measurements of renal function in these individuals. The mathematical formula that resulted calculates an estimated GFR (eGFR) based on a variety of factors, including age and sex. It also uses a so-called “race co-efficient,” which adjusts eGFR for Black patients based on the assumption that they have more muscle mass. While researchers developed a refined equation in 2009, race remained a factor.

In a presentation during the American Society of Nephrology’s (ASN) Kidney Week in October 2020, University of Pennsylvania nephrologist Nwamaka Eneanya said that the race co-efficient is the legacy of three small, flawed studies that were published between the 1970s and 1990s. The scientists who developed the eGFR failed to question these findings, as have researchers who refined this formula and the physicians who continue to use it, she says.

The downstream effects of such a miscalculation, Harhay suggests, aren’t academic, either. A Black patient and a White patient could have the exact same serum creatinine levels, but because of the race co-efficient, she says, the Black patient would be seen as having higher kidney function. That could mean the White patient is eligible to be listed for a transplant, while the Black patient is not.

An October 2020 study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine quantified this impact. When Salman Ahmed, a nephrologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and colleagues removed the race multiplier from their eGFR calculations for 2,225 African American patients who had chronic kidney disease in one health care system, they found that one-third would be re-assigned to a more severe stage of disease. Indeed, the adjusted eGFR values would be enough to bump as many as 3.1 percent of African American patients higher up on the donor waiting list.

While some medical systems have already done away with the race co-efficient, and while the ASN and the National Kidney Foundation have formed a joint task force to review it — with a final report planned for spring 2021 — for now it remains widely used.

The inclusion of race in the formula, critics say, is one of the many reasons that Black people with kidney disease experience delays in care. Indeed, according to an analysis of data from 1990 to 2009, Black patients waited an average of 2.5 months longer than White patients for a kidney transplant. And while that gap has narrowed in more recent years, experts suggest that studies like this don’t even capture the full picture, because until 2014, time on the waitlist was measured based on when a person had formally been deemed eligible for transplant, not when their kidneys had failed. And other analyses have routinely shown that minorities wait far longer on dialysis before being referred for transplant in he first place.

In December 2014, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network formally changed the kidney allocation system rules to begin marking time on the waiting list not by the date a person qualified for transplant but by the date they began dialysis. A primary goal of the new rule was to reduce racial disparities in kidney transplantation, and while multiple studies have found the change did just that, a 2019 paper in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases suggested that the new rules may have created other problems.

In any event, getting on the transplant list at all still requires patients to mount numerous hurdles, as patients like White have discovered.

Looking back at his first six months on dialysis in 2009, White had to admit that he didn’t look like an ideal kidney transplant candidate. He struggled to find transportation to and from the dialysis center, and he often skipped appointments. White also found it hard to adjust to the strict dietary and fluid restrictions prescribed to him by the dietitian at the dialysis center. Then there were the handfuls of medications he had to take each day. White found it tough to afford them and to stay on top of filling his prescriptions.

“I was like the rebel in my dialysis clinic,” White said of his behavior. But beneath the surface layers of rebellion and indifference lay an intense internal struggle. White’s diagnosis of kidney failure had turned his life upside down. Although he had retired prior to his diagnosis, he was looking for work again when his kidneys failed. The physical health challenges that dialysis patients like White face often lead to mental health issues in addition to financial ones. As a result, the first few months of dialysis treatment tend to focus on stabilizing patients and helping them adjust to their new reality, whether it’s traveling to a dialysis center three times each week or dialyzing at home. In all these challenges, discussions about transplant or any type of long-term treatment often get lost, says Plantinga. “Maybe that conversation about transplant occurs, but it occurs a couple months later,” she said.

Whether or not patients bring up the topic of transplant when they start dialysis, Harhay says that dialysis providers have regulatory requirements to educate them about the potential benefits of kidney transplantation. Patients who are interested in transplant must then be evaluated at a transplant center, where numerous factors are considered in assessing their candidacy, including a patient’s overall health, how well they can follow their treatment plan for kidney disease and co-occurring conditions like diabetes and hypertension, their ability to take medications as prescribed and show up for dialysis, and their insurance coverage for everything from the transplant itself to anti-rejection medications. If a patient has a consistent record of missed dialysis treatments or chooses not to take their medications, Harhay says, transplant physicians are likely to worry about their ability to take care of their transplanted organ, because post-transplant, missing medications can lead to organ rejection.

Transplant nephrologist Dr. Meera Harhay says adequate support for patients is critical. “You can imagine why these challenges would be that much more overwhelming if a patient’s support system or financial resources were limited,” she wrote.

There are “subjective pieces that are really hard to measure. They make decisions about who’s a good candidate, which tends to happen behind closed doors,” Plantinga said.

In Harhay’s experience, patients with fewer financial resources certainly have larger hurdles to overcome when trying to achieve optimal health care, she says. “To ‘comply’ with dialysis treatment means attending all treatments (usually at least three, four-hour treatments per week), restricting fluid intake, avoiding certain foods, and taking a lot of medications,” Harhay explained in a follow-up email. Similarly, to “comply” with transplant means being able to attend regular clinic appointments and take medications, some of which have bothersome side effects or require high out-of-pocket costs, even with insurance coverage.

“You can imagine why these challenges would be that much more overwhelming if a patient’s support system or financial resources were limited,” Harhay wrote, adding that when her patients are provided with adequate support, they do well.

A report from the Transit Cooperative Research Program shows that lack of reliable transportation to and from dialysis clinics is a major problem for patients. Researchers from Fresenius Medical Care, one of the country’s two leading dialysis providers, found that patients who missed dialysis appointments were more likely to be non-White, according to a 2014 study in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. Adherence to diet and medication regimes also vary by race, and studies suggest that non-White kidney failure patients have greater difficulties in these areas. Research also shows that low rates of health literacy disproportionately affect those in lower socioeconomic brackets and non-Whites, which a Clinical Nephrology paper showed can impact crucial measurements of kidney disease management.

While Harhay says she doesn’t know the role implicit bias plays in assessing transplant candidates, a 2018 study by Plantinga and others showed little awareness among nurse managers and other providers about racial and ethnic disparities in transplant waitlisting, especially those in the U.S. South and among White employees. A 2015 focus group study by McAdams-DeMarco found that Black patients reported concerns about medication, fear of organ rejection, and a lack of information about transplantation. A separate study that same year, led by Melissa Wachterman at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, found that misconceptions about the risk of transplantation and concerns about the quality of donor kidneys appeared to temper many Black dialysis patients’ enthusiasm for transplant.

What White heard were the horror stories from his fellow patients, about transplants that had failed, and people who had died. It didn’t sound any better than being on dialysis, which gave him little motivation to change. White says he struggled to come to grips with his kidney failure diagnosis for about six months, and it wasn’t until the clinicians at the dialysis clinic and his wife sat him down in April 2010 for a chat that he was able to grasp what his kidney failure diagnosis meant. The social worker provided him with the information necessary to apply for disability and get hooked up with public transit assistance and the local food pantry. From then on, White went to dialysis three times a week, took his medication religiously, and made an effort to stay within limits of sodium, potassium, phosphorous, and water in his diet.

“I learned the more effort that I put into creating a better life for myself, the more it actually comes true,” White said.

As White’s mental and physical health improved, he began to chafe at the restrictions dialysis placed on his life. Having switched to nighttime dialysis, he found it difficult to sleep and thought “there’s gotta be a better way.” In 2011, two years after his kidneys had failed, White asked his social worker about getting a transplant. But when he called the first transplant clinic on his list (White declined to say which one), the very first thing the receptionist said was that they wouldn’t see him unless he could prove that he could pay for the transplant. While White acknowledges all clinics want to make sure patients can afford the procedure and follow-up care, he was put off by the tone of the response he got. A 2018 analysis of more than 3,200 dialysis patients in Chicago published in Clinical Transplantation revealed that Black end-stage renal disease patients were one-third less likely to be placed on the transplant waitlist than White patients. In a 2015 study, scientists from the University of Illinois at Chicago found that White men have twice the chances of completing an evaluation for a kidney transplant than Black men.

Because he lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C. White could find three other hospitals with transplant programs, something not available to those living in more rural areas. Since White doesn’t have a car, he relied on public transit not only to get to and from dialysis but also to attend the countless medical appointments needed to qualify for a transplant. It’s a dizzying process that even well-resourced, health literate people can struggle with, says Amy Waterman, a transplant educator at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The key is where is it breaking down for someone who would love to get a kidney transplant but never knows about it, is scared of it, didn’t make it through all the evaluation process, didn’t have a car to get to the transplant center to get evaluated, got ruled out for something that they could have changed, but never changed it,” Waterman said.

Simply referring a patient to transplant may not be enough to ensure that someone gets the medical care that they need. Other barriers exist, too. Spanish speakers may find other problems with transplant referrals, such as receptionists who don’t speak the language or no translators available at appointments, says Cervantes.

Once they begin the transplant process, patients must not only qualify medically for a transplant, they must also qualify financially. Callender calls this the “green screen.” The purpose of the screening is simple, he says. To prevent their bodies from rejecting their new organs, transplant recipients have to take daily immunosuppressant medications. They also need to cover the cost of associated appointments and expenses that insurance doesn’t. With demand for organs far outstripping the supply (in the U.S., nearly 92,000 people are currently waiting for a kidney), transplant clinics don’t want to give an organ to someone at high risk of losing it because they can’t afford medication.

After overcoming so many obstacles, White knew he had to find a way to get the dental work he needed prior to his transplant done. Keeping him on dialysis would cost Medicare an estimated $90,000 each year for the rest of his life, but if White couldn’t afford to pay $1,500 to $2,000 to have his teeth fixed, a transplant would be out of the question. On a Friday evening in 2014, White saw a segment on the news about a Catholic charity providing free care in nearby Columbia, Maryland. He paid nearly $400 to rent a car and drove to Columbia the next day.

To Callender, the ability to break down these barriers is much of what drew him to medicine more than a half century ago. Born in New York City in 1936, Callender became interested in medicine as a child, when he heard a sermon about caring for bodies as well as souls. Hospitalized for 18 months as a teenager for tuberculosis treatment, Callender spent his time reading the Merck Manual — a medical textbook — from cover to cover. After graduating from medical school, Callender pursued surgery. Following a residency at Howard University, he then moved to Nigeria to fulfill his dream of becoming a medical missionary. While there, however, he lost 40 pounds and decided to return to the United States. He ultimately completed a transplant surgery fellowship at the University of Minnesota before returning to Howard University, where he’s been ever since.

Callender had lived and breathed health disparities over his multi-decade career, but one of the issues that stuck with him was how few Black individuals signed up to be kidney donors.

In a pilot study funded by a $500 grant from Howard University Hospital, he and colleagues conducted interviews with 40 Black men and women and found that many participants lacked awareness of the need for organs by Black patients. Many of those interviewed also had religious concerns about donating, even after death. By providing education and answering questions, Callender found he could get most people to sign up by the end of the interview process.

Drawing on the information gathered during this initial study, in 1982, Howard University Hospital and the National Kidney Foundation created the District of Columbia Organ Donor Project (DCODP). In just seven years, the DCODP had increased the signing of donor cards by the city’s Black residents from 25 per month to more than 750.

With funding from the Dow Chemical Company, Callender took his program on the road, speaking about the need for Black organ donors in cities across the country. Callender’s efforts had helped transform the racial and ethnic landscape of kidney donation. Between 1990 and 2008, the proportion of deceased donor organs that came from minorities increased from about 18 percent to 33 percent, and the number of organs donated by African Americans nearly quadrupled. By 2010, according to a study by Callender, organ donation rates by Black Americans exceeded that of White Americans, where they have remained. In 2020, data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network through the month of October showed that nearly 16 percent of deceased organ donors were African American, whereas they comprise only 13.4 percent of the population.

“What we’ve seen is something that is also miraculous in that ethnic group that people said would not donate has actually become the number one donor ethnic group in the United States of America,” Callender said.

Despite such changes in organ donation, Black patients on dialysis are still far less likely than White patients to receive a living donor kidney. Some of that is due to the nature of the social networks from which people try to find donors. Given the country’s stark racial divides, Americans tend to have more friends from a similar racial and ethnic background. Black patients, then, tend to reach out to fellow Black family and friends. The higher burden of kidney disease in that population, Waterman says, along with co-occurring conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, makes it harder for acquaintances to qualify to become living donors. Then add on other burdens, such as difficulty taking time off work, paying lost wages, and concerns about medical and life insurance, and it’s not surprising that the disparity exists, she concludes.

A lower number of minority living kidney donors also creates its own disincentive as people thinking about donating don’t see kidney donation as an activity done by people who look like them. It’s why Waterman developed a campaign to share stories of people from all walks of life who have acted as living kidney donors. Potential donors need to be able to put themselves in the shoes not just of those who need a transplant, but of those who are willing to help.

“It just needs to be normal. You can donate blood, right? You can donate a kidney,” Waterman said.

In June 2015, after nearly six years on dialysis, White got the call he was waiting for. The George Washington University transplant center had a kidney for him. It took 10 days for his kidney to start functioning after the transplant. He didn’t realize he had regained the ability to produce urine until it began leaking out of his catheter.

“It was impossible to measure but it was impossible not to smell, and that was a pretty good smell, all things considered,” he said. “I hadn’t made urine in almost six years, so I didn’t mind the smell one bit.”

Meanwhile, when Gee finally received a deceased donor kidney in April 2017, he was so grateful for his gift that he has since devoted his life to advocating for the Black kidney disease community. Besides educating the public on end-stage renal disease, he also speaks to hospitals and governments about policy and the realities of life with kidney disease. Gee’s new goal is to live long enough to see his youngest grandchild (currently just over 1 year old) graduate from high school.

“My worst day with a transplant,” he said, “is better than my best day on dialysis.”

This series was supported in part by the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.

Carrie Arnold is an award-winning freelance science journalist based in Virginia. In addition to Undark, her work has appeared with Scientific American, STAT, National Geographic, Wired, and The New York Times, among other publications.

Larry C. Price is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning documentary photographer and multimedia journalist based in Dayton, Ohio. He previously produced award-winning photography and video footage for Undark’s Breathtaking series on air pollution, which won a George Polk Award for Environmental Reporting in 2018.

PROFIT & LOSS: THE COMPLETE SERIES