For the past few months, almost every headline beginning “coronavirus testing” has made my heart sink.

Rather than following the lead of nations like South Korea, which recognized long ago that widespread testing is the cornerstone of an effective pandemic response, Western governments were initially slow to commit to scaling up testing capacity. As poor testing numbers hit the headlines, some, like the U.K., tried to massage those numbers to give the illusion that they were making greater progress than they were. In the U.S., President Donald J. Trump took an even more extreme tack, proposing that the country “slow testing down” in order to suppress reported case numbers.

None of it worked. By playing politics with coronavirus testing numbers and subsequently getting caught, governments undermined public faith in their data. But they also distracted us all from what has, in many respects, been a tremendously successful scientific effort to develop, scale up, and deploy coronavirus tests around the world. While the political story of coronavirus testing is anything but uplifting, the scientific story offers a lot more hope.

Let’s start at the beginning. The first cluster of unexplained and alarming pneumonia cases, later revealed to be Covid-19, was reported to the World Health Organization on December 31, 2019. On January 10, 2020, Chinese scientists shared with the world the first draft genetic sequence for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. Within a week, scientists at the German Center for Infection Research in Berlin had used that sequencing data to develop the first test — a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test — capable of detecting specific genetic sequences unique to the novel coronavirus.

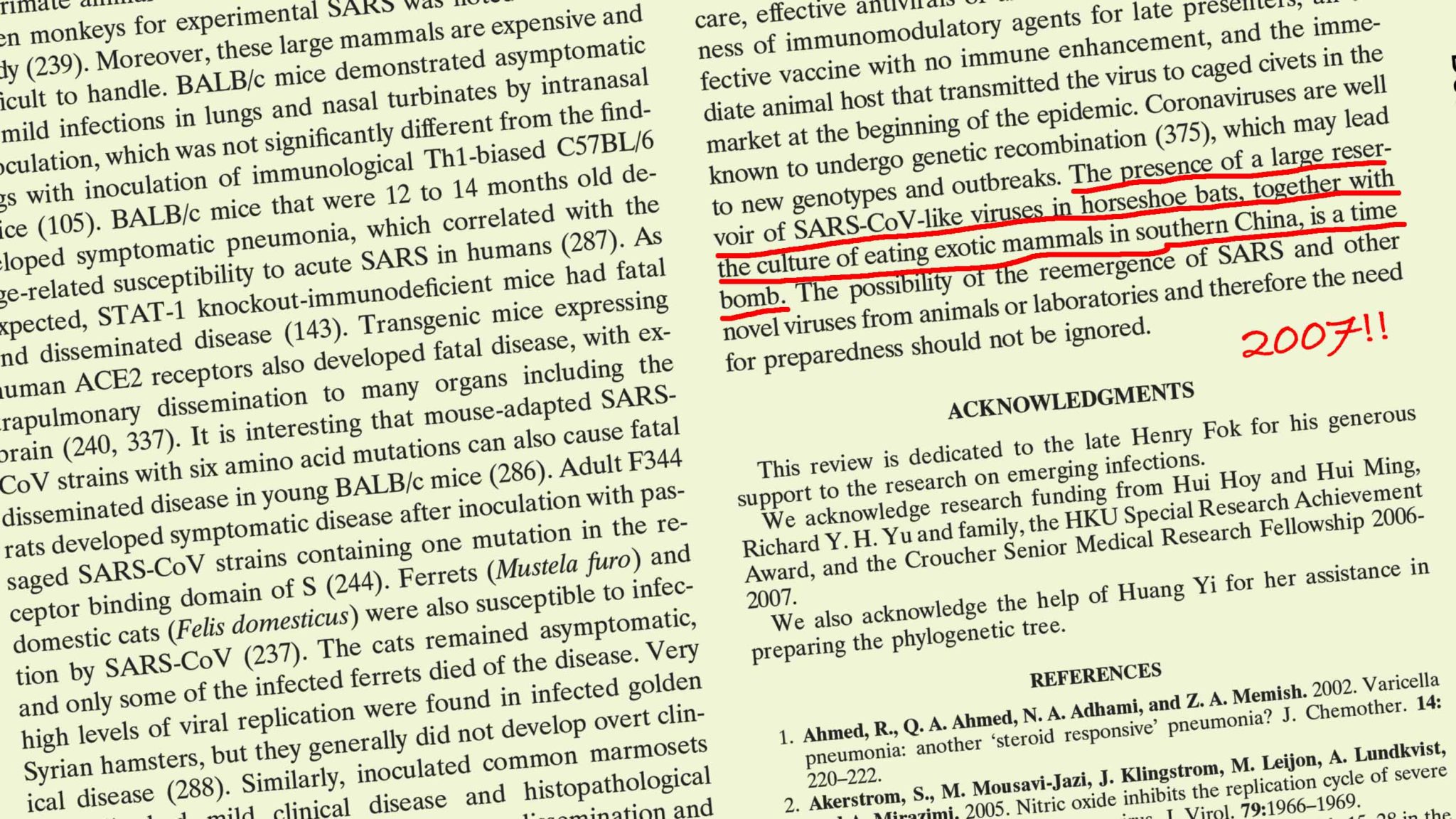

And so, less than a month after the first case was reported, the first lab-based tests for SARS-CoV-2 were ready for use. Such a rapid timeline would have been almost incomprehensible just 10 years ago. By contrast, it took almost six months to develop the first PCR test for the virus behind the SARS outbreak, SARS-CoV-1, that burned through China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore in 2002 and 2003, nearly becoming a global pandemic of its own.

Once the technology was available to test for the virus, focus shifted to getting those tests into play. Having learned from their past experiences, East Asian nations led the way. By the end of January, genetic sequencing goliath BGI Group had already distributed 50,000 coronavirus testing kits across China. By the end of February, South Korea had processed more than 85,000 tests.

Meanwhile, Western nations were struggling to scale up their testing capacity. Industry, however, was quick to respond. Scientific and pharmaceutical giants like Thermo Fisher, QIAGEN, and Roche moved to ramp up manufacturing, and by the end of March, millions of new testing kits were making their way off production lines and into circulation.

But testing kits are useless without the staff and equipment to process them. In places like the U.K. and the U.S., that processing was initially done mostly in hospitals and public health labs. But as March turned to April and demand for tests grew, governments needed to find other ways of boosting their testing capacity.

The U.K. government took a quintessentially British approach, calling on its network of universities and research laboratories to support the national effort. Researchers and students answered the call for volunteers in droves, setting aside their own research projects and Ph.D. theses to focus on testing Covid-19 samples. They used the equipment they had available in their labs, innovating as best they could to maximize efficiency. Sir Paul Nurse, chief executive of the Francis Crick Institute in London, likened it to the pandemic equivalent of the Little Ships of Dunkirk, referring to the fleet of hundreds of private boats amassed to rescue Allied soldiers in northern France during World War II. Then, on April 22, the U.K. finished setting up the Lighthouse labs network, a partnership of high-capacity diagnostic labs capable of processing tens of thousands of samples every day.

With testing capacity increased, the challenge became finding ways to get tests to the people who need them. With most of its population stuck at home in lockdown, the U.K. embraced a new approach: home delivery kits. In late April, Amazon announced it would begin using its vast network of warehouses, trucks, and drivers to deliver Covid-19 tests to homes all across the U.K., allowing people to remain isolated at home if they thought they had the virus. Royal Mail, the U.K.’s postal service provider, also began helping to deliver and swiftly return tests for processing. These two partnerships enabled the U.K. to turbocharge its testing program, almost doubling the number of tests performed each day from around 30,000 to almost than 70,000 in the space of less than a week.

The combination of more testing and enhanced public health measures dramatically drove down the percentage of tests that return a positive result, or the test positivity rate. In mid-April, that rate was over 15 percent in the U.S. and the U.K. By early July, it had fallen below 9 percent in the U.S., according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the U.K. and other parts of Europe, official websites indicated positivity rates below 5 percent, one of the WHO’s indicators that a Covid-19 outbreak is coming under control. Although the journey is far from over, with labs in the U.K. struggling to manage recent surges in testing demand — and the efficiency and testing validity of the Lighthouse labs network, along with at-home kits, being called into question — progress has certainly been made from the slow start back in March.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

Now scientists have turned their attention to creating faster, cheaper, simpler, and more portable tests. We’re already seeing promising innovations on that front, from Columbia University’s simple coronavirus “spit test” to a smartphone-driven test from the Universities of Brunel, Lancaster, and Surrey in the U.K. Both tests can turn around a result in just 30 minutes, and don’t need to be sent out to a lab. Meanwhile, researchers in China and Israel are taking the first steps toward a Covid-19 breathalyzer test, which could give an on-the-spot result in under a minute.

Such rapid, affordable, and portable testing for SARS-CoV-2 — even if not as accurate as traditional lab tests — could open up a world of opportunities to quarantine more effectively, and quickly become the most powerful tool we have to slow the spread of Covid-19 and get back to “business as normal.” In the face of rising case numbers across Europe and the U.S. — and recent antibody studies from London and New York indicating that the goal of herd immunity remains far off — these new tests offer a much-needed ray of hope.

To be sure, the rollout of coronavirus testing has been far from a fairy tale story. Global leaders failed to learn from the lessons of the past, were inexcusably slow in prioritizing the scale-up of testing capacity, and chose squabbling and finger-pointing over close international collaboration. Sadly, in both Russia and the U.S. we’re already starting to see the same political machinations play out in the hunt for a vaccine.

But take heart: If the story of coronavirus testing has shown us anything, it’s what the global science community — academia, industry, and public bodies alike — can accomplish when they come together and dedicate themselves to a common goal. Let’s hope that our political leaders give our scientists the space and the funding they need to carry on, and that they’ll listen to them a little earlier next time.

Aran Shaunak is a freelance journalist and science communicator with an academic background in human biology, pathology, and the spread of infectious diseases.