To Preserve Jobs for Humans, Some Propose a Robot Tax

Slowly but surely, human workers will be pushed into the shallow end of the job pool, according to Daniel Susskind, a fellow in economics at Balliol College, Oxford University. In his book “A World Without Work,” released earlier this year, Susskind argued that advanced artificial intelligence programs and robotics will eventually match or outperform human workers across industries.

“As machines become more and more capable, human beings will find themselves retreating to an ever-shrinking set of tasks and activities that these systems and machines cannot do,” he told Undark.

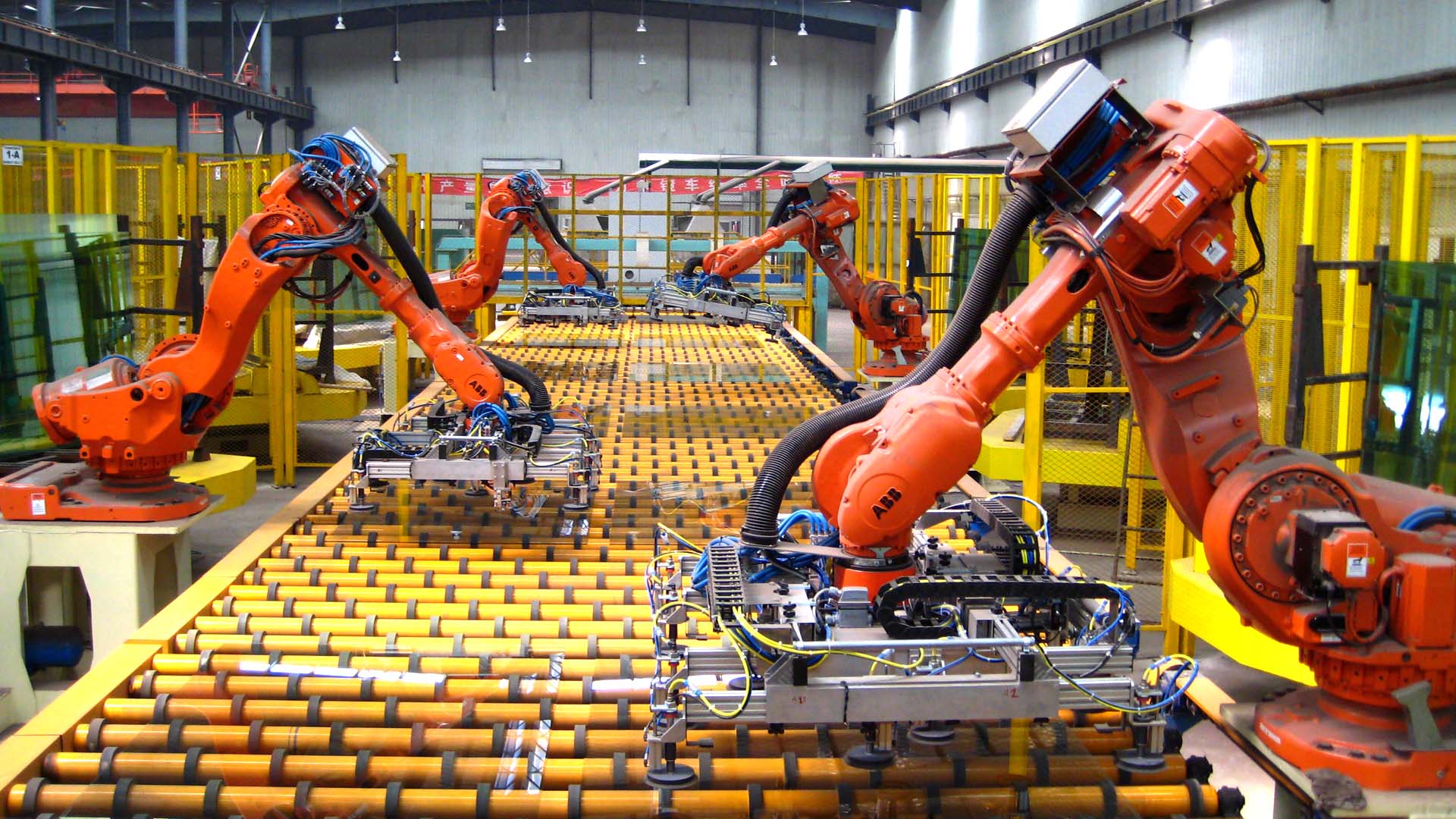

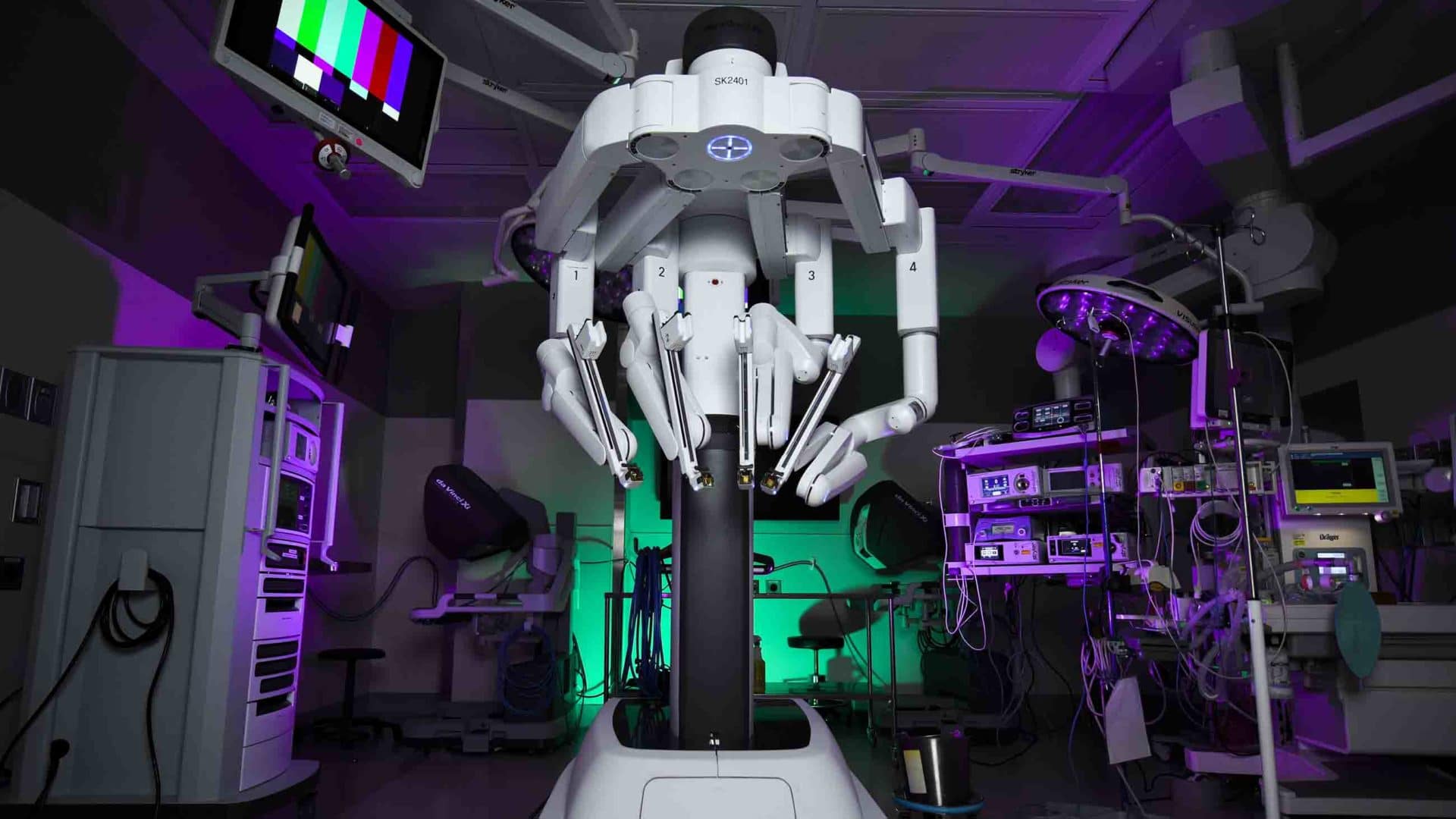

Machines have already found steady work in the manufacturing and automotive industries. More recently, they’ve made headway in law, medicine, and even art. And as the machines gain more skills that were previously thought to be unlikely or even impossible, it might not be a surprise that automation anxiety remains strong.

In the last few years, some academics, politicians, and business leaders have been advocating for a robot tax — a sum companies pay whenever they replace workers with robots and computer programs. The funds would go to social services or to retrain workers displaced by automation. But critics argue that automation isn’t something to fear: It ultimately creates new kinds of jobs, or at least will never reach the point of replacing every human worker. What’s more, some experts say that the threat of a future pandemic like Covid-19 is another reason to encourage automation, as machines and programs are immune to disease and could eventually help mitigate the harm to the economy and infrastructure

So far, no country has introduced a robot tax. In 2017, the European Commission voted to regulate robots, but shut down the notion of taxing them. In Canada, former Green Party leader Elizabeth May advocated for the creation of such a tax during the country’s 2019 election. But some companies are experimenting with a kind of self-imposed robot tax. For instance, in 2019, Amazon announced it would spend $700 million to retrain 100,000 workers in the United States as it continues to automate warehouse tasks.

Among the more well-known supporters of the robot tax are Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates, who both argue it would protect workers from future unemployment.

“Right now, the human worker who does, say, $50,000 worth of work in a factory — that income is taxed and you get income tax, social security tax, all those things,” Gates said in a 2017 interview with Quartz. “If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think that we’d tax the robot at a similar level.”

Economists regularly debate the extent to which machine workers can affect human jobs. In a 2013 paper, Oxford University economist Carl Frey and machine learning researcher Michael Osborne used expert opinions and a type of artificial intelligence called machine learning to rank 702 jobs in the U.S. The ranking ranged from the most likely to be automated — which the duo identified as telemarketers — to the least likely to be automated — identified as recreational therapists. The paper concluded that 47 percent of the jobs it surveyed were at a high risk of automation, including some surprising positions, from restaurant hosts to models to pest control workers.

The paper, an early effort to augur the future of human work, is often debated. Critics say the number of jobs that Frey and Osborne claimed are at risk was too high. One problem, they say: The figure ignored realities in the world of work, including the differences between jobs of the same name and the range of tasks within a job.

But other research points to a similar trend. In a 2019 paper, Stanford University economics Ph.D. candidate Michael Webb employed a subset of machine learning called natural language processing — used to analyze data sets in human languages — to find overlap between technology industry patents and job descriptions gathered from the U.S. Department of Labor. The paper posited that machines will eventually be able to take on a surprising variety of white-collar tasks, like interpreting medical imagery or researching legal documents.

“These are indeed the kinds of occupations that haven’t seen this kind of automation before,” Webb said.

And in science labs, machines are learning to work in other startling fields. In 2017, a team of researchers at Rutgers University released Artificial Intelligence Creative Adversarial Network (AICAN), a program that can create visual art, either autonomously or in concert with a human. The computer program’s vivid, dream-like paintings have appeared in galleries and festivals in the U.S. and Europe. One appears as a prop in the HBO series “Silicon Valley.”

Even computer coders may not be immune: In 2017, scientists from the University of Cambridge and Microsoft Research released Deepcoder, a program that can learn to write code by piecing together elements from other programs.

In the future, the bulk of computer programming could be performed by machines, said David Womble, a mathematician and director of artificial intelligence programs at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee.

Researchers at ORNL are already looking at how machine learning may apply to manufacturing and energy production, among other fields. Such demands require complex computer code and powerful computers. To keep up, programming may have to increasingly rely on automation, Womble said.

“Maybe we have to get to a point where we don’t even have a concept of code,” he added, when people lose the skill almost entirely.

If these developments, and others in the future, turn the job pool into a job puddle, a robot tax could be used as a stop-gap measure to retrain people into the remaining jobs, which may also end up automated, until policymakers develop new systems to provide for humans, said Xavier Oberson, professor of international tax law at the University of Geneva. A guaranteed livable income — a social support where a government gives every citizen enough money to pay for basic needs like food, electricity, and housing — is one example.

While automation could eliminate onerous tasks and increase productivity overall, it could also eliminate vast swathes of jobs, leaving social security nets around the world to fray as tax dollars from labor decrease, Oberson said.

“I’m not so pessimistic,” he added, “but at least we should consider that this risk exists.”

Not everyone agrees that a future without human workers will happen. Ahmed Elgammal, the Rutgers professor heading AICAN, said the program is more of a creative partner for human artists to use, rather than a replacement for artists. Similarly, Womble noted that humans may still be involved in creating computer programs, even if that only means directing which programs need to be made.

Webb suspects that companies will redesign jobs to free up human employees for what they excel at — like interpersonal relations — while pushing precise, repetitive, and dangerous tasks onto machines. Future technology will be used to augment workers, he said, not replace them. For example, mining was a dangerous career for many people, but now there is a move to let machines handle many of the worst parts while humans work in the office.

In a 2017 paper, Terry Gregory, an economist at the IZA – Institute of Labor Economics in Germany, found that, in contrast to Frey and Osborne, only 9 percent of jobs had a high risk of automation. In response to the controversial 2013 paper, Gregory suggested that machines can rarely replace all of a human worker’s skills. A 2017 study from the American management consulting firm McKinsey & Company also reported that only 5 percent of careers consist entirely of tasks that can be automated.

It’s also rare for the same job to always describe the same type of work, Gregory said: “So, two secretaries working at two different jobs — they may have the same occupation, but they do very different tasks.”

Other experts argue that automation has historically created more jobs than it destroys, and that this trend will likely continue. A 2018 report from the World Economic Forum on the future of work suggested that while machines will remove 75 million jobs by 2022, another “133 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labor between humans, machines, and algorithms.”

In a 2016 paper, Gregory examined this phenomenon in Europe between 1999 and 2010. He found that, in the wake of automation, productivity increases and prices decrease, stimulating demand for more labor, rather than less. Also, the profits from automation are spent in the local economy, creating more jobs that way. And that’s not to mention the jobs that are created to build, maintain, and operate the new machines and programs.

But this growth could come with a period of displacement, when workers’ skills don’t line up with the needs of the job market or people simply don’t live where the jobs are. This period can be hard on workers, particularly in countries with weaker social supports and fewer workers’ rights, said Dan Breznitz, Munk Chair of Innovation Studies at the University Toronto, as well as co-chair and fellow of the CIFAR Program on Innovation, Equity, and the Future of Prosperity.

Periods of displacement also often include a rollback on workers’ rights. For example, as rapid, innovation-based growth — including but not limited to automation — rolled out in Israel starting in 1970, the gap between the rich and poor widened. According to 2019 research out of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, though automation has increased productivity, it has also “weakened workers’ bargaining power in wage negotiations and led to stagnant wage growth.”

The lag between old jobs vanishing and new jobs appearing may also be, or at least feel, quite long. In “The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation,” released last year, Frey looked at the period of displacement in England during the first Industrial Revolution. He found that for the seven decades following the revolution, wage and quality of life declined for people with lower socio-economic status — even though the country’s overall productivity increased.

“I think it’s important to remember when economists speak about the short term, they’re not very precise about what that is and whether it’s 70 days or 70 years,” he said. “It kind of makes a difference.”

The history of automation from Dickensian London to Silicon Valley has been “bumpy,” Frey added. But it remains to be seen if the next round of technological innovation will look anything like the past. Gregory believes that there is value in looking at automation’s history of creating jobs, though he does note there is a question about job quality. However, he noted, that any research trying to posit the future of automation would be speculation and, right now, modern automation still isn’t understood well enough and there is no convincing economic rationale to warrant a tax, he said.

Frey and Breznitz agree that automation creates jobs, but that economic inequality is still rampant throughout many places. According to the United Nations’ World Social Report 2020, 71 percent of the world’s population live in countries that struggle with the issue. In 2018, U.S. billionaires had a lower tax rate than the working class, The Washington Post reported. Meanwhile, corporate tax rates around the world have decreased.

Instead of a robot tax, which could hit technology that creates new jobs, Breznitz and Frey recommend raising taxes on huge corporations. Taxing the mega-rich, in some cases, could also be used to foster equality. A robot tax, Breznitz said, “looks to me like blaming the messenger, instead of treating the real problem.”

During pandemics like Covid-19, taxing robots could also stifle productivity in heavily automated industries, Frey told Undark by email. While human workers are sick or quarantined, automated transportation, warehouses, and retail services can keep providing for people because these types of viruses don’t affect machines, so inhibiting them could further harm the economy and slow some of the services and goods they provide.

But other economists, including Oberson, think establishing a robot tax is pressing now. To work, such a tax will require international agreement — no country would want to be the only one to give up the competitive advantage of automation — and figuring out the best way to implement it could take a long time. Figuring out how to implement a measure only when or if it is needed would leave unemployed workers in a lurch, Oberson said.

Though some researchers argue that automation can provide for people during outbreaks like Covid-19, businesses using more machines — and fewer humans who can get sick — could be sheltered from the disease and make more money, Oberson said. If they faced a robot tax, it could help to fund healthcare and other supports on which Covid-19 is currently placing immense strain.

Even though there is little consensus, Susskind is optimistic. Imagine the world’s economy as a pie, he said. For much of human history, the pie was simply not large enough for everyone to get a reasonable slice. Now, with technological progress, the pie is large enough. “We have come incredibly close to solving the traditional economic problem which has haunted us for centuries,” he said. “How do we make that pie large enough in the first place?”

In the long run, Susskind believes the issue isn’t automation taking jobs. It’s about how the pie is divided. With the future of automation, jobs as they exist today won’t be able to divvy the pie up fairly, he said. The idea behind a robot tax seems useful, but it has some issues, he said. It needs a clearer definition of what a robot is — computers are already present and performing tasks in most peoples’ jobs to some degree, so should they also be taxed? And any automation-related tax would also need to be made in such a way that it avoids curbing the benefits of automation.

“The basic principle underlying it — that we need to find a way of taxing the owners of this increasingly valuable capital — has to be right,” he said.