Robot-assisted surgery is big business. Increasingly, surgeons are going into operating rooms equipped not just with their two hands but with robotic arms outfitted with miniature cameras, forceps, suturing tools, and other surgical instruments. Surgery can now be performed from across the room by someone seated at a computer console. Last year Intuitive Surgical, the leading manufacturer of surgical robot systems, shipped more than 900 units of its most popular model, the da Vinci, each priced at roughly $1.5 million. In 2018, the global market share for surgical robotics was $5.4 billion, and it’s predicted to leap above $24 billion by 2025.

And for good reason. Acting alone, surgeons can operate only on what their eyes can see, and basically the only way to see inside a patient is to cut them open. With surgical robots, tiny cameras and tools can be inserted through a small incision, a “keyhole,” to perform fiddly procedures with exquisite precision. The minimally invasive approach is meant to promote faster patient recovery times and reduce postoperative complications. It may also lessen the physical toll on the physician: Long hours in the operating room are less demanding when the surgeon works from a seated position.

With the mechanization and miniaturization of surgery, however, comes a side effect that has the capacity to add a completely new dimension to health care. Massive amounts of data detailing every snip, clamp, and stitch that takes place in the operating room could be made available for collection and analysis. Before robotic surgery “you had a surgeon who was operating, and nobody else knew what was going on in there,” explains Khurshid Guru, one of the earliest masters of surgical robotics. But what if everybody — medical trainees, hospital administrators, insurance companies, even the robots’ manufacturers — could follow along?

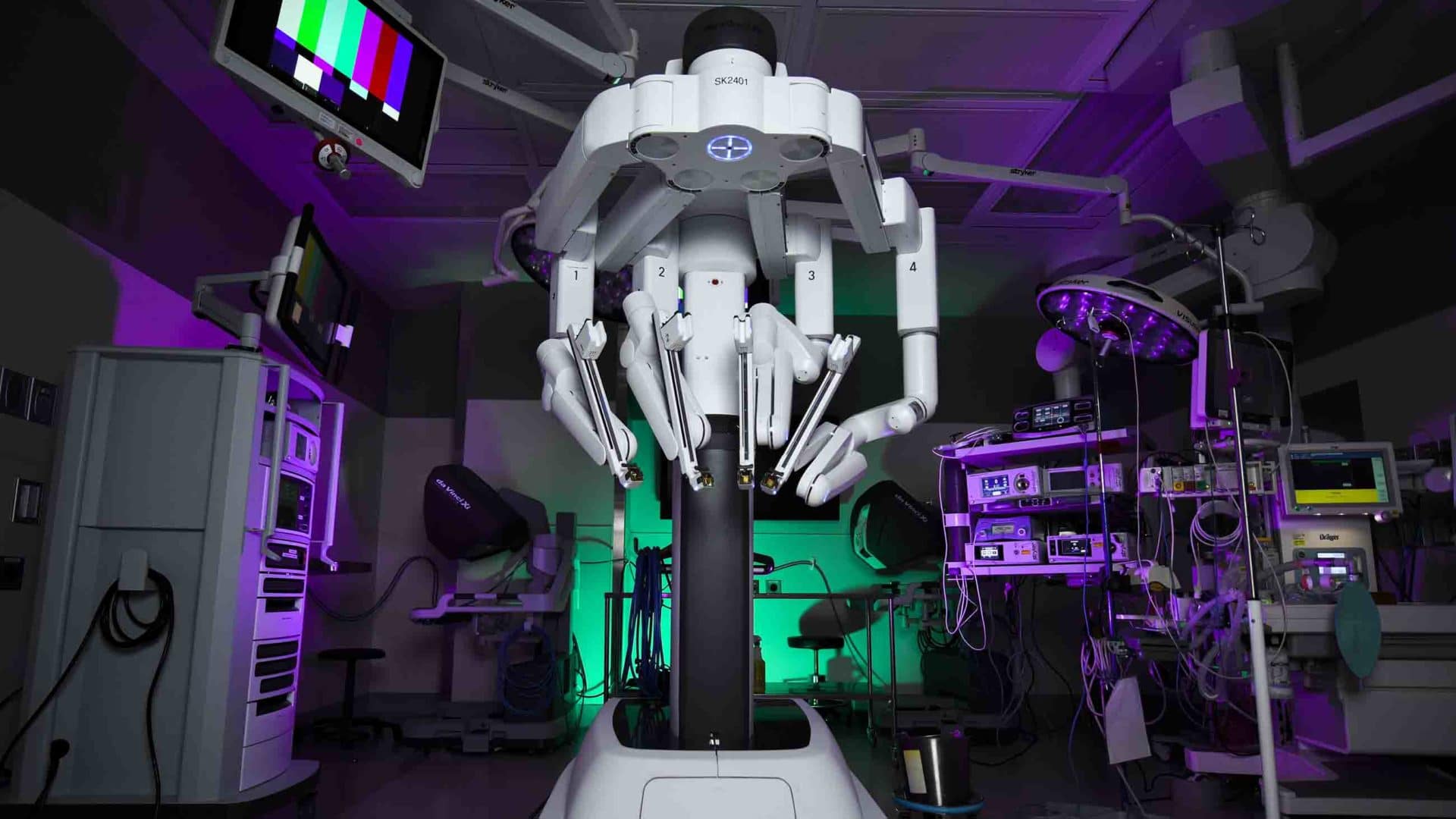

The da Vinci, the most popular surgical robot in use today, resembles an oversized, four-armed tarantula. In 2018, more than 1 million procedures were performed worldwide with the da Vinci, up from 136,000 in 2008. Roughly three in four of those procedures were performed in the U.S.

As with other surgical robots, video and movements from the da Vinci can be recorded. On its face, that data could become a valuable training tool, with apprentices receiving detailed feedback about their performance in the operating room. In an article published in 2017, researchers were able to analyze a robot’s movements during a suture or other discrete task to tell whether it was controlled by a “novice” or “experienced” robot surgeon. Guru, who leads the robotic surgery group at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, has even monitored the surgeons’ brain activity, assessing the focus and stress levels of novices and experts.

But how much data is too much? The American health care system is already subject to seemingly unending measurement. The National Quality Measures Clearinghouse, a database maintained by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, lists more than 2,500 metrics that can be used by insurers, government agencies, and other groups to assess the performance of health care providers. An American College of Physicians committee recently studied a subset of those measures and concluded that only 37 percent of them were valid and meaningful indicators of physician performance. Robot surgery data could end up adding more noise than clarity.

It could also add considerable emotional stress to an already-stressful profession. A report this year from the Massachusetts Medical Society, Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, and Harvard University cited survey results suggesting that 78 percent of U.S. physicians experience burnout, a crisis the authors attributed to “a ‘collision of norms’ between a historical investment in physician professional autonomy and a new era of measurement and accountability targeting quality, errors, inequities, and soaring costs.”

The act of collecting and analyzing data about a surgeon’s every move could put the surgeon under intense, protracted scrutiny. The numbers and rankings that a student earns during their surgical training could plausibly follow them throughout their career. What if administrators decide that a young medical student’s cognitive activity makes them unsuitable for a surgical career? What if they review a doctor’s careful performance and deem it — by algorithmic virtue — to be “inefficient”?

Almost certainly, the data will be used to try to improve surgical outcomes. To date, studies on surgical robot performance have been focused on small groups of trainees, but researchers want to expand their scale. One could imagine that, over several years, the surgical skills of an entire urology department could be assessed, with specific hand movements tracked against patient outcomes.

The temptation will be to use that data to hone in on the “perfect surgery.” But who would decide which metrics to prioritize? An under-staffed hospital might push its doctors toward faster surgery times at the expense of patient recovery times. Insurance companies, poised to start using the data to decide individual hospital reimbursement rates, will likely have their own priorities.

Guru thinks certification organizations like the American Board of Surgeons should hold responsibility for regulating robotic surgery data, and for prioritizing performance outcomes. The first universal priority should be causing “no harm to the patients,” he says, followed by improving patient outcomes.

Jim Torresen, professor and head of the Robotics and Intelligent Systems research group at the University of Oslo, sees the issue through a slightly different lens. “People have described the latest developments in artificial intelligence as ‘a tsunami of progress,’” he says, “but I think the same could not be said of robotic surgery, where the progress is in small incremental steps.”

Torresen expressed concern about the effects of overregulation. Researchers in the U.S. and Europe using data from robot-assisted surgeries already have to follow strict patient privacy protocols. Torresen thinks this is slowing down the speed of robot-surgery research and limiting collaborations. He believes most patients would be amenable to sharing more of their data, if they felt it would help themselves and others.

Robotic surgery is the future. Electronic data collection is the future. To be sure, some data generated by robot-assisted surgeries will benefit patient and physician alike. Patients have a right to hold medical institutions to account and to know whether they risk greater surgical complications at a particular hospital — or with a particular doctor — before they go under the knife. Recording every detail of a surgical procedure may also offer surgeons protection against patient litigation.

When it comes to data, however, more isn’t always better. Added information doesn’t always confer added wisdom. We now have to decide: Just because we can measure something, does it mean that we should?

Claire Jarvis is a scientific and technical writer covering the interface of chemistry, biology and medicine. Her writing has appeared in Chemistry World and The Open Notebook. She can be found on Twitter (@StAndrewslynx).

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I still await the first article showing superiority of using the robot over not using it for any operation

It is not very comfortable to think that technological tyranny may eventually control and subdue every human activity. Once the slide starts there is no going back.

It’s stressful for cops to wear bellycams. They too are responsible for public safety and are subject to high levels of burnout. The building trades affect people’s safety as well, and members can get nervous when an inspector or customer is watching them work. (I have worked in and written for and about the electrical industry for many years.) Still, in my opinion hey have the right to watch, so long as they don’t get in the way. In this model, who’s exempt? I’d say the purely verbal, intellectual operator: the remote-meeting attendee, the work-from-home contractor. This is simply because their product is all that needs to be judged.

yes, we need also the shirgical robot here in all congo kinshasa.

contact+243994238406