Experts Race to Set Rules For Deciding Who Lives and Who Dies

With the fast-spreading SARS-CoV-2 virus overwhelming hospitals and leaving crucial life-saving equipment in short supply, doctors and other health care providers in Italy, Spain, and possibly elsewhere, have had to make grim, battlefield decisions over who gets a ventilator or an intensive-care bed, and who does not. Or, put more fundamentally: who lives, and who dies. It’s a bleak scenario that other nations, including the U.S., may soon face. Even as tents, soccer fields, and unused buildings are being converted to makeshift hospitals to accommodate the surge of Covid-19 patients, current modeling suggests that in many U.S. cities, health care resources could soon be exhausted as the number of critically ill patients swells.

In some areas, shortages are already apparent, and should they find themselves facing similar moments of triage, where a decision must be made as to who gets a life-saving piece of equipment and who does not, American health care providers — and their counterparts around the globe — currently have an imperfect collection of ethical guidelines, most of them never really tested in the real-world, to inform them.

|

Got questions or thoughts to share on Covid-19? |

“These discussions have never gotten beyond the abstract before,” said professor emerita of emergency medicine and bioethicist Jean Abbott of the University of Colorado. “We had some warning with SARS and concerns with H1N1, but it never hit the fan anywhere near the extent it is now.”

Of course, clinicians, ethicists and others have been preparing for these types of scenarios for years, including in the aftermath of the SARS threat in 2003. Guidance on how resources could be fairly rationed during an influenza or other pandemic were also already in place when the Covid-19 pandemic first surfaced in China in December. But as hospitals across the globe scramble to assemble triage teams, ethicists are now working to improve this existing guidance so that it’s better tailored for the unprecedented nature of Covid-19.

Existing recommendations, for example, often rely on metrics such as the amount of time a patient might need a ventilator, or their “SOFA” score, which assesses the likelihood of sequential organ failure. Unlike other illnesses where patients only need a ventilator for a few days and worsen over time, however, Covid-19 patients — especially those who are younger — require ventilators for weeks, exacerbating the shortages and accelerating a potential point of reckoning: If two patients are dying and only one ventilator is available, who should get it?

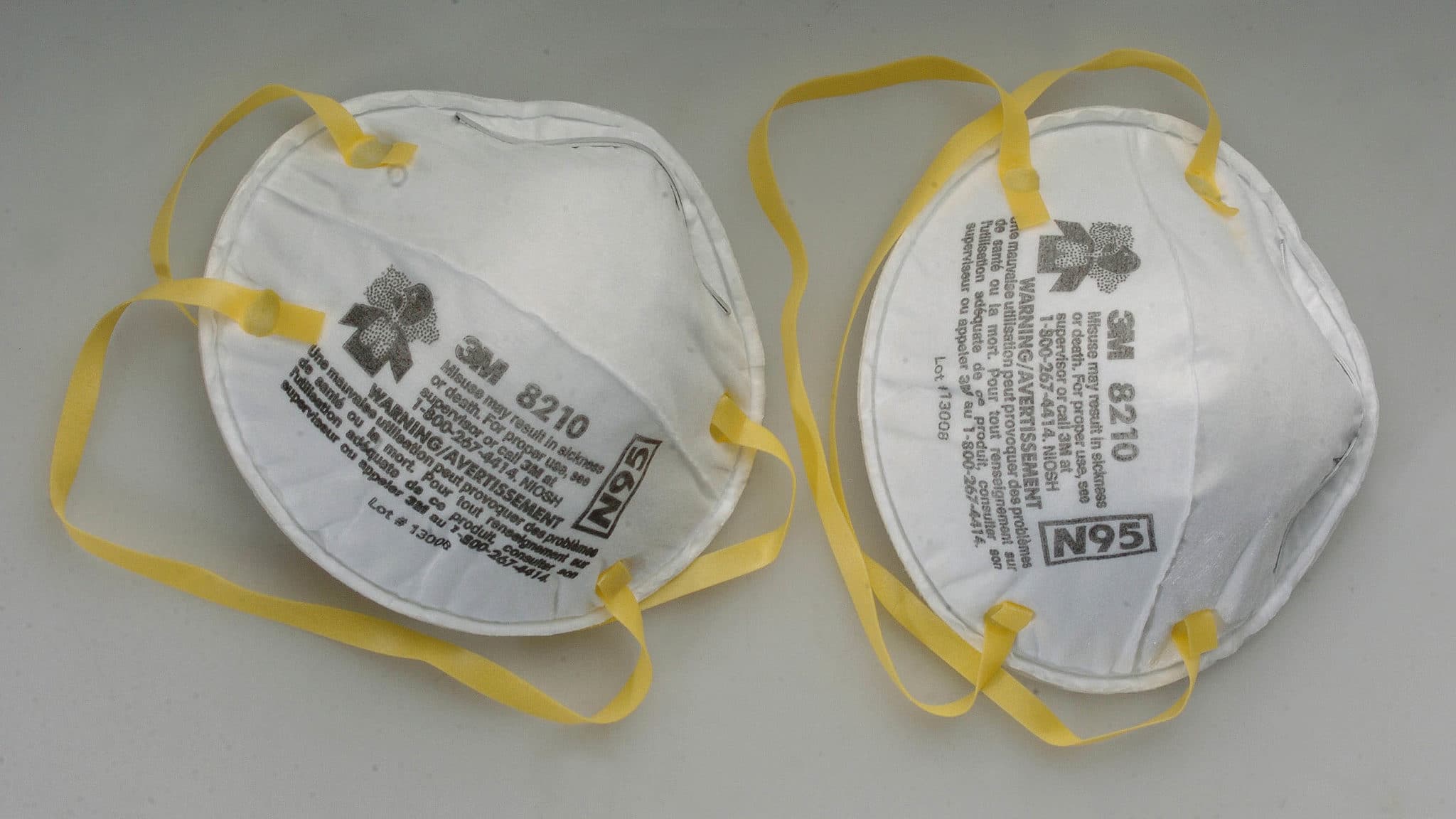

Concerns about discrimination in such cases — or even random, ad hoc decision-making — are now high, as U.S. hospitals are already running into shortages of personal protective equipment and ventilators, and some adaptive measures are already in play. Non-Covid-19 patients who would otherwise need ventilators because of worsening chronic lung disease, for example, may now be intubated instead — an option that’s not recommended for Covid-19 patients. The state of Washington has already allowed some concessions on personal protective equipment for health care workers, permitting the re-use and conservation of masks and other protection.

For now, clinicians and triage teams in the U.S. have not been driven to make the most difficult choices, and if measures such as quarantines, mass testing, and contact tracing are put into place, it may never come to that. “This is an unusual circumstance where there’s a huge threat to public health, but these measures could save thousands of lives if implemented,” said Douglas White, a professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “We want to do whatever we can to essentially be on the Titanic and not hit the iceberg.”

But as the Covid-19 pandemic worsens, that iceberg may well prove unavoidable, and far more consequential decisions may need to be made. That has experts in bioethics now racing to provide clear, ethical, and equitable guidance should health care teams have to make a life-and-death call regarding the allocation of care and equipment.

Broadly speaking, existing guidance documents, such as this one from Tennessee, cover standards for care for two distinct scenarios: a contingency, and a crisis. The guidance is region-specific: State departments of health gather data from regional hospitals on the resources, so that ventilators or patients can be transferred between facilities during times of contingency. This avoids individual hospitals in a region running into crisis-mode quickly. For instance, when a northern Colorado hospital’s intensive-care unit filled up last week, patients could be quickly transferred to another facility, according to Abbott. The U.S. is already well into contingency-mode, “where we don’t degrade the quality of care, but we do get inventive,” Abbott said.

This is where soccer fields are turned into tents, elective procedures are avoided, and retired doctors or nurses are asked to return to work. But more extreme measures are already pushing some American health care facilities toward the line between contingency and crisis. These include measures now being used in some hospitals that share ventilators between critically ill patients. “Ventilator splitting is a bit on the edge between contingency and crisis,” Abbott said. “Maybe we should call it extreme contingency, if you will.”

Crisis standards of care would extend far beyond this. As patients flood hospitals and intensive-care resources dwindle, health care workers could step into a grey area where they must choose between caring for the patient before them, and considering the greater good of society as a whole. Such decisions about who receives care — and who doesn’t qualify — are not supposed to be made by clinicians on the intensive-care unit floor, experts note, but by a triage team that typically includes a doctor, an ethicist, and a chaplain or other staff member. Unlike doctors in wards, the triage team is ideally blinded to a patient’s ethnicity, gender, or financial means. That distinction is crucial to avoid biases and long-term trauma, because “no one comes off a triage team without damage to themselves,” Abbott said.

It’s easy to see why. “An individual’s best interests may not be the same as the greatest possible good for the greatest number of people,” says Mark Tonelli, a critical care physician and ethicist at the University of Washington. Tonelli has helped draft guidance on coping with disasters for decades, and he’s quick to clarify that crisis standards of care don’t equal no standards — or even random ones. “It means we really focus on providing the greatest good for the greatest number. That’s a switch from the medical ethos of trying to do our best for the one patient in front of us.”

Instead of allocating resources to every patient in need, crisis care standards suggest prioritizing those most likely to benefit from an intensive-care unit bed or equipment such as ventilators. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services had developed a Pandemic Influenza Plan in 2005, subsequently updated most recently in 2017, which attempted to model resource stressors for moderate and severe outbreaks — though this did not account for health care systems being completely overwhelmed. And the World Health Organization maintains a database of documents that contemplate various ethical questions related to pandemics.

As cases began to skyrocket in Italy, the Italian College of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) issued recommendations that have been described as a “soft utilitarian” approach to rationing resources. German physician associations have also recently agreed on a suite of ethical guidelines for crisis decision making. Uwe Janssens, president of the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (DIVI), said such decisions must be medically justified and fair, according to German broadcaster Deutsche Welle.

Other recommendations for crisis health care rationing used around the world have specifically excluded certain groups of people when resources are scarce, such as those with advanced liver disease or heart disease. And even now, advocates for patients with disabilities say that the guidance provided in some states, such as Washington and Alabama, are unfair to people with severe mental retardation or those in a persistent vegetative state.

Documents circulated online from some hospitals have been criticized for discriminating against patients facing emergencies unrelated to Covid-19. For instance, guidance from Washington suggests that when resources are scarce, patients may be recommended to palliative or out-patient care — rather than receiving intensive care support — depending on their “baseline functional status.” The instructions read: “Consider loss of reserves in energy, physical ability, cognition, and general health.”

(On Saturday, the Office of Civil Rights within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a notice to health care providers that discrimination “on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, age, sex, and exercise of conscience and religion” is prohibited by federal law — “including in the provision of health care services during Covid-19.”)

Tonelli, who helped develop Washington’s decision-making plan, says the guidance there is based purely on a patient’s odds of improvement if they receive a ventilator or other resource. Those odds are determined by their prognosis — not intellectual capacity, ethnicity, or other factors. “We don’t consider anything that’s not of direct prognostic value,” Tonelli says. “For instance, if someone is blind or paraplegic or has intellectual disability, none of that enters into the calculation.” (Tonelli made clear that he is not speaking as a representative of the University of Washington Medical Center, which has now been named in federal complaint by disability groups challenging the state’s guidelines.)

Elsewhere, Douglas White of the University of Pittsburgh and his colleagues have developed a rating system that assigns patients priority scores based on who is most likely to benefit. The goal is to help triage teams decide how to allocate resources based on broad ethical principles. For instance, if the framework scores three patients as equally likely to benefit from a ventilator, but one of the patients is much younger than the rest, age may be the tiebreaker. “That’s not because the younger person has any more intrinsic worth or social value, but because they’re the worst-off in the sense that they’ve had the least opportunity to live through life,” White said.

Another tiebreaker involves critical workers, who should receive greater priority for ventilators or other interventions — not only to honor their contributions, but to further public health response. “We should prioritize people who are critical to saving other lives — not just doctors and nurses, but also the hospital workers who clean rooms between patients,” White added.

Other researchers recommend additional metrics to ensure fair and equitable access to healthcare even during a crisis. For example, treating patients on a first-come, first-serve basis could bias care to those who live closer to hospitals, or those who were more diligent about self-quarantine — and thus waited longer at home before seeking needed care.

A March 23 article in The New England Journal of Medicine, co-authored by 10 researchers, epidemiologists, bioethicists and other experts, lays six guiding recommendations for rationing during the Covid-19 pandemic specifically: “Maximize benefits; prioritize health workers; do not allocate on a first-come, first-served basis; be responsive to evidence; recognize research participation; and apply the same principles to all Covid-19 and non–Covid-19 patients.”

Maximizing the benefits of any decision — that is, doing whatever will potentially save the most lives — is the most important, the authors write. Because of this, they note starkly: “We believe that removing a patient from a ventilator or an ICU bed to provide it to others in need is also justifiable, and that patients should be made aware of this possibility at admission.”

In videos widely circulated on social media last week, doctors and other health care providers in Spain lamented the yawning shortages of ventilators there, and the harrowing decisions they’ve had to face as a result. In one heartrending video, a doctor is moved to tears as he shares a report from a colleague in Madrid, where there are too few doctors and nurses to match the patient population, too few beds, and too few ventilators, forcing a decision to favor life-saving interventions for those under 65. The elderly, unable to have visitors, are sedated and allowed to die. “We can’t let them die in this unworthy manner,” the doctor says.

So far, the U.S. has avoided this fate, and efforts are underway to shore-up dwindling medical supplies. These include announcements made by U.S. President Donald J. Trump last week — after intense criticism of the administration’s missteps and foot-dragging in response to the growing crisis — that the government would purchase thousands of ventilators produced by a growing number of companies to help address the nation’s looming shortfalls. This comes about a week after nearly 1,400 bioethicists wrote an open letter to the White House imploring it to use federal powers to ramp-up production of medical devices and an equipment that will be essential to fighting the pandemic.

Still, it remained unclear whether this and other moves would be enough to prevent the possibility that American medical teams, too, will soon face the hardest possible decisions over who lives, and who dies, when not everyone can be treated. And while recommendations such as randomizing patient names to decide who gets a ventilator may seem excessive, ethical dilemmas that once seemed confined to war zones and history may soon unfold in cities and towns across the U.S.

Whatever the vagaries of each policy, experts say, there will be no easy answers. Health law researcher Govind Persad of the University of Denver compares such scenarios to a classic ethics dilemma: When faced with two sinking islands and the opportunity to only save one, would you fly a rescue plane to the island with a population of one person, or the island with five residents? “Most people, ethicists or otherwise,” Persad said, “would agree that it makes more sense to save five people instead of one.”

That would be cold comfort, of course, to the sole residents of many islands, and to the families who would like to see them saved, too. But in triage, Persad suggested, hard choices are unavoidable. “It’s easy to pick on a guidance and say look, this guidance could lead to that tragic choice,” he said. “But it’s important to consider what the alternative might be, and the cost of that alternative.

“It’s not the guideline that’s forcing a traumatic choice,” he added. “It’s the fact that we don’t have enough ventilators.”

Jyoti Madhusoodanan is a science journalist based in Portland, Oregon. She covers life sciences, health, and STEM careers for Nature, Science, Scientific American, Discover, Chemical & Engineering News, and other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

DOuglas White (University of Pittsburgh) suggests priority for saving younger people :”they’re the worst-off in the sense that they’ve had the least opportunity to live through life,” is blatant Ageism!