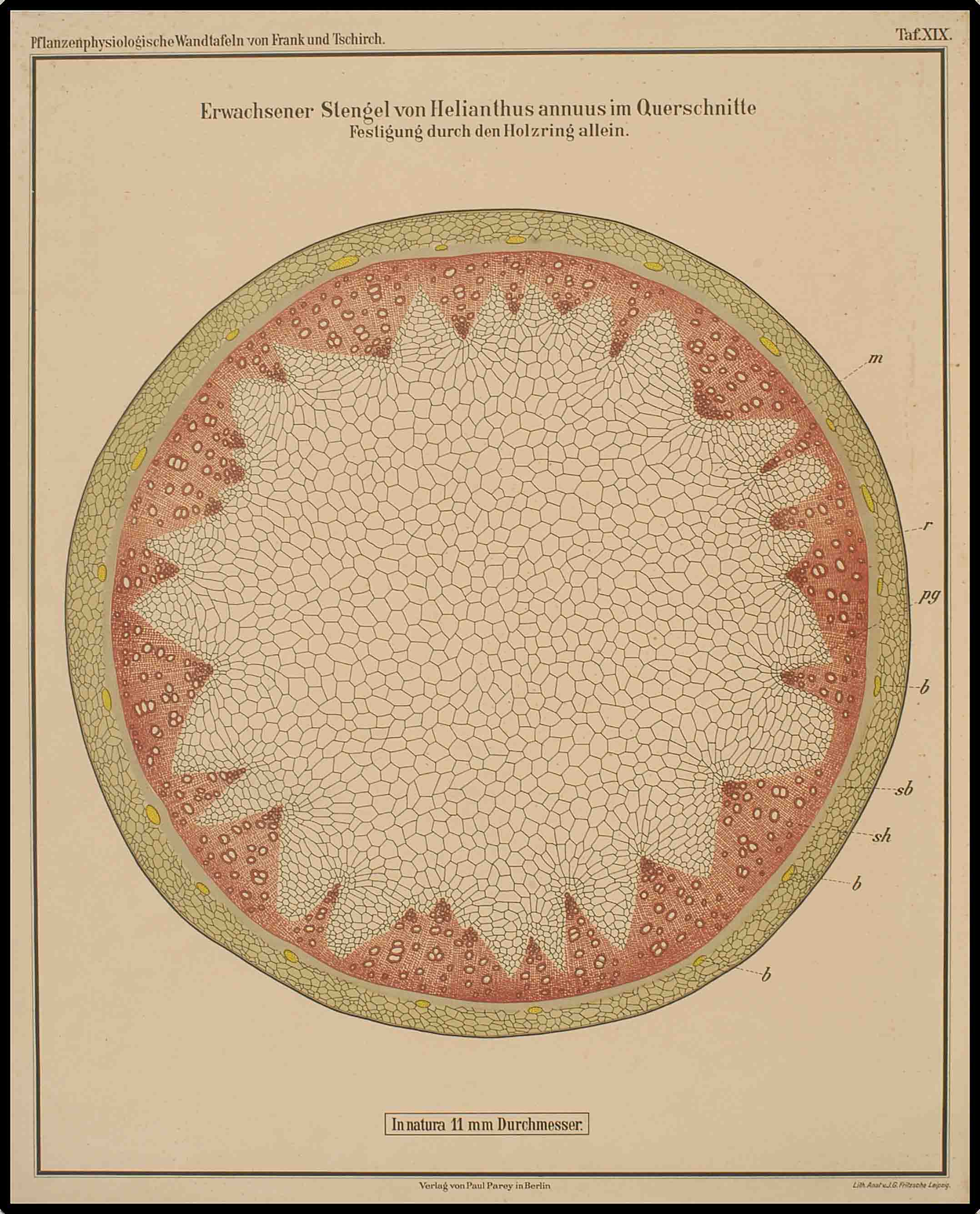

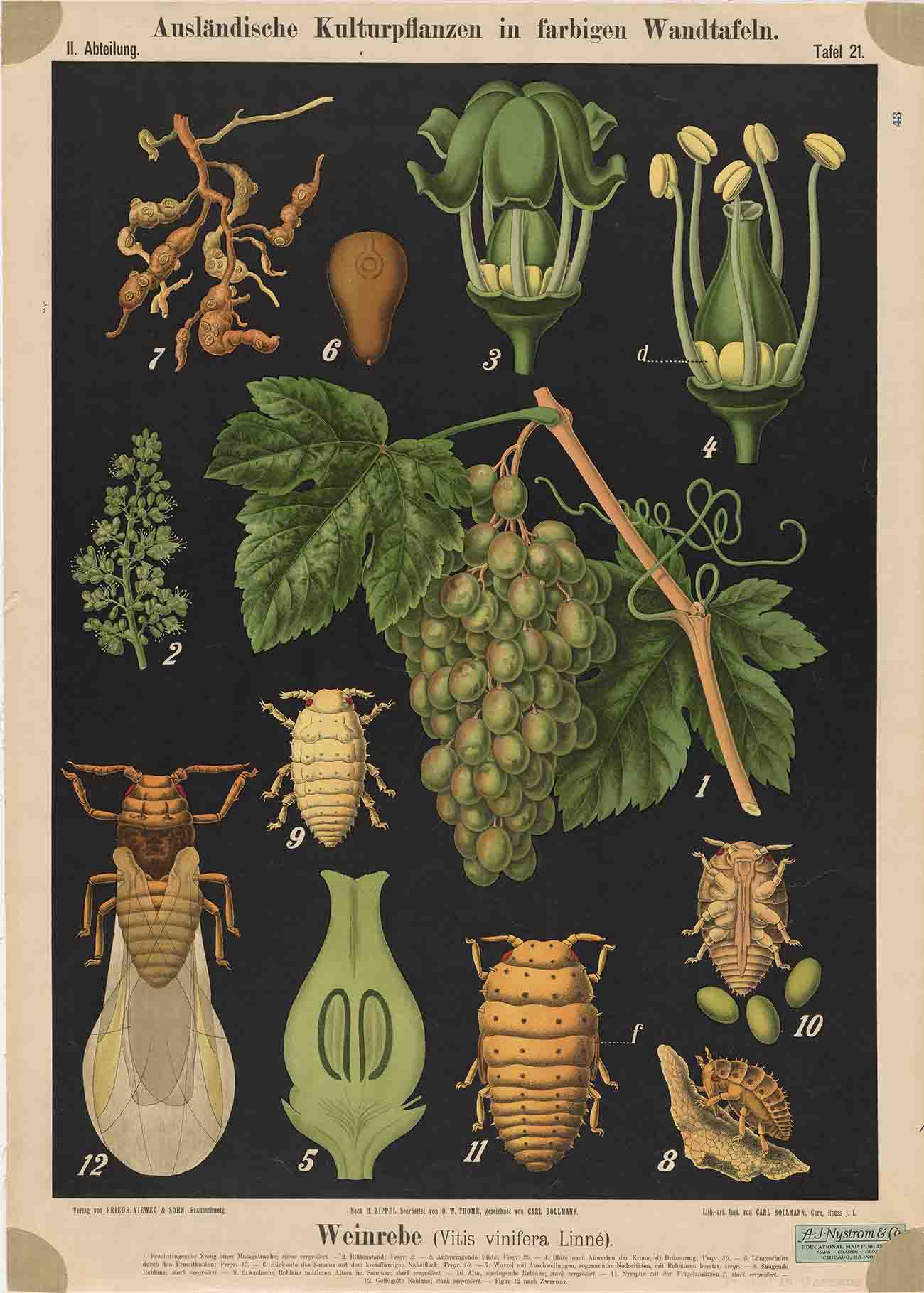

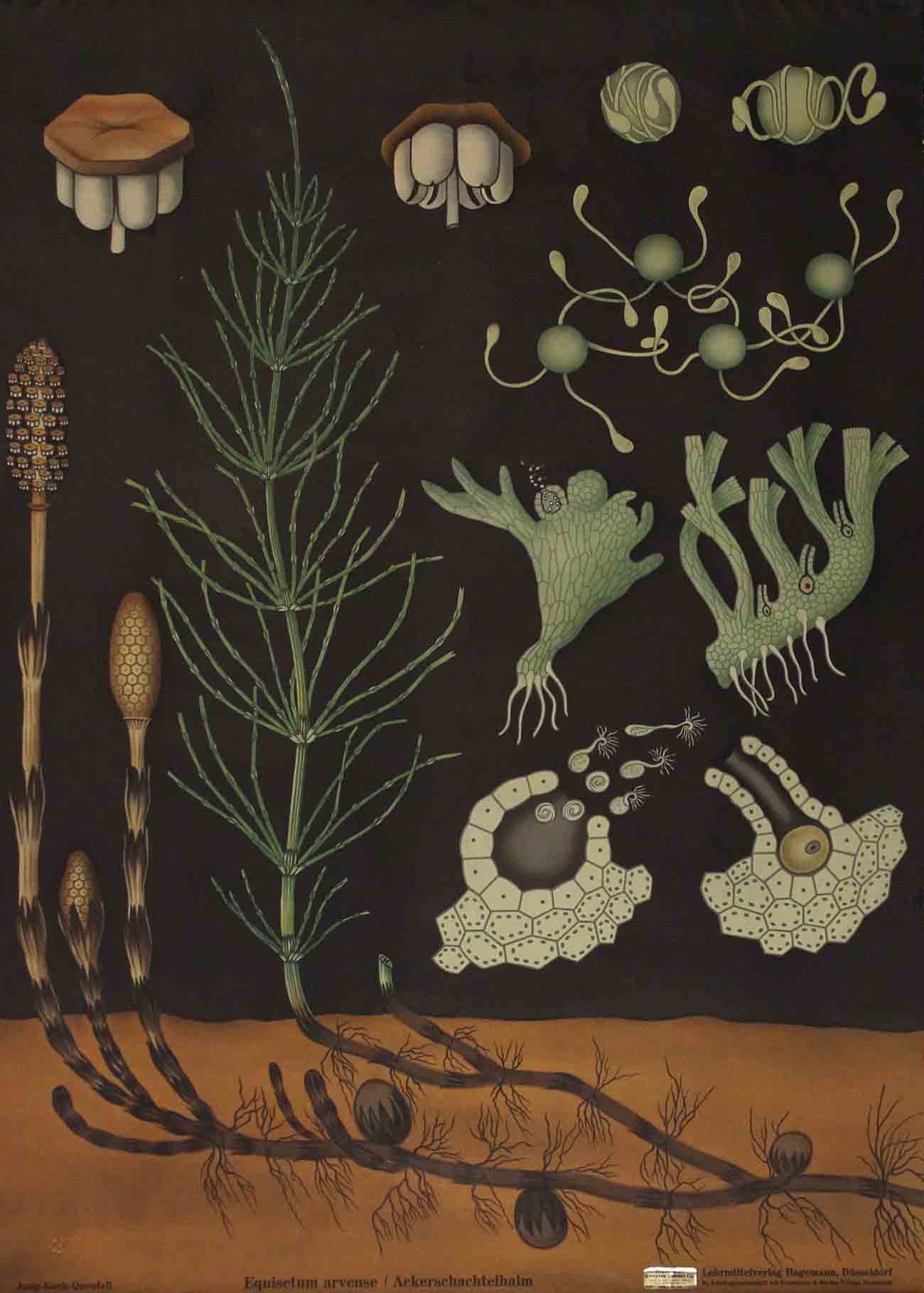

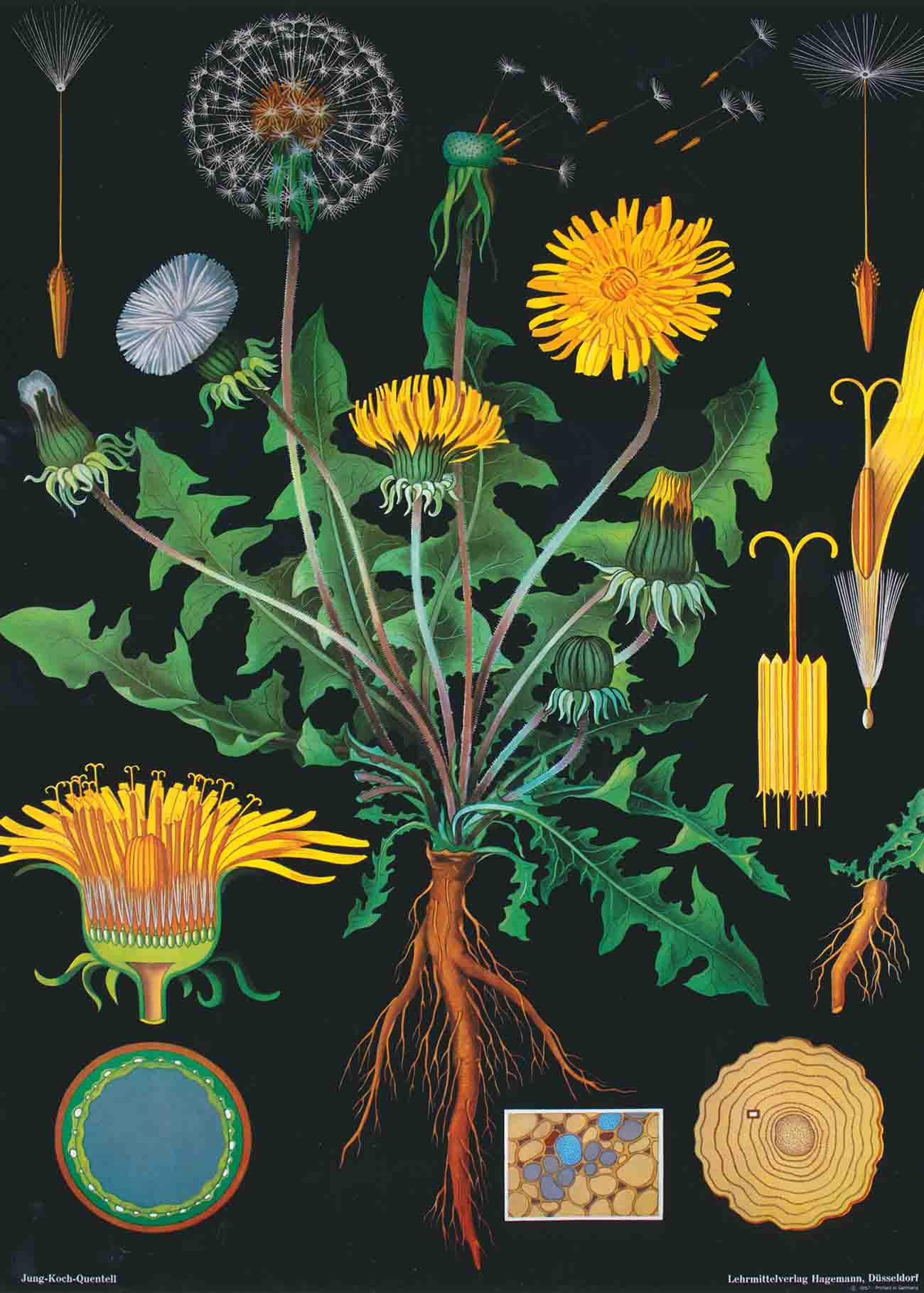

Meticulous and beautiful, the charts in this book belong to a lost age — a time not only before digital photography but before modern photography of almost any kind. Most come from Europe in the late 19th century, a golden age of scientific discovery in which scientists were exploring the globe and there was a clamor for knowledge of the natural world.

These illustrations are from Anna Laurent’s book “Botanical Art in Golden Age of Scientific Discovery” (University of Chicago Press).

Pedagogical curiosity was hardly limited to elite universities and the salons of the privileged. Education was now considered a right afforded to all. And there was no shortage of botanic illustrators with scientific expertise; in the absence of photography, botanists were compelled to seek alternative visual media for depicting plant anatomy and reproduction.

In assembling “Botanical Art From the Golden Age of Scientific Discovery,” I was especially interested in the social context of each chart and in the variety of ways in which illustrators and authors depicted the same species and plant families, depending on their pedagogical intent, or botanic perspective.

Many of Europe’s charts were destroyed after World War II, or merely decayed for lack of preservation; after all, they were produced as teaching tools, not fine art. Those that persist are collected in archives, universities, museums, herbariums, and libraries throughout the world. Many remain in dusty cabinets. I found a collection of several hundred in the Berlin herbarium, rolled and tied with brittle twine, undisturbed for over 50 years. I found another at a university in Prague, where they were still in circulation and used in classroom lessons. (I have not found them in use anywhere else; largely, they have been replaced by digital media.)

Even when archived and indexed, the collections lack contextual information about the authors, illustrators, publishers, and original curricula. Many of my conclusions were drawn from detailed comparisons of their content, and inferences about their intended context. An 1868 poster of economic grasses for a Czech audience, for example, prominently features an insect in the center of the chart; upon discovering that the beetle is a persistent pressure on rye grass, I concluded that one of the chart’s primary purposes was to familiarize students with the insect for identification in the field, suggesting the chart would have been presented in an agricultural context.

In many cases, the charts were authored (and sometimes illustrated) by botanists themselves. Rather than publish an academic paper announcing the results of a 10-year experiment, scientists instead published a series of wall charts and companion textbook. Lithography assisted the propagation and distribution of wall charts; in many cases, however, a student would be enlisted to illustrate a single chart for a professor’s coursework. Either way, a series would reflect the content of a course, or the author’s interest. The director of a botanic garden in Cologne, Germany, for example, was concerned about his country’s putative ignorance of poisonous plants, so he commissioned a series titled “Poisonous Plants of Germany.”

In France, a couple named Rossignol designed very simple charts for their rural elementary school children. Despite their deliberate educational purpose, the wall charts demonstrate artistic liberties and decisions by their illustrators. Flourishes, textures, shading, symmetry, negative space, color, and line are all elements that distinguish one chart from another of the same species. Among Victorian-era botanic illustrators, science and art were inextricably bound.

Anna Laurent is a writer, producer, and photographer who has collaborated with botanic gardens, including Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum and the University of California, Berkeley. She has been a contributing editor of Garden Design and a columnist for Print magazine.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Not a single link to buy the book? Come on!

All you have to do is click on the pic of the book.

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/press/contact.html

Order it directly from the press. And check out their other titles – they’re just as wonderful!