Amid Fear and Men With Guns, Polio Finds Safe Refuge

In a crowded square in the ancient Nigerian city of Kano, outside the palace of one of the Emir’s princelings, a menagerie of community leaders gathered this spring to combat an age-old foe. Mullahs, musicians, dignitaries, doctors, and traditional leaders, the last swathed in robes and turbans, are all enlisted in an elaborate public-service extravaganza — one orchestrated to both distribute and increase awareness of polio vaccine.

Young women draped in blue hijabs and armed with iceboxes full of life-saving, sugar-pink elixir, vanish into labyrinthine alleys and crumbling, crowded houses, as the citizenry watch the show from behind police barricades. They are men in the pale cotton tunics and finely-worked fula caps of the Hausa majority, women with bright veils tucked around their faces and babies in their arms, and scores of bug-eyed kids. Is the virus lurking among them?

By last summer, it had been almost three years since the last polio case in Kano state, and for a moment it seemed it might go down in history as the last in all of Nigeria. It wasn’t to be.

Visual: Undark

It might well be. Poliovirus is so cunning, so contagious, so devastating, that a single case of Poliomyelitis, the paralysis-inducing disease it causes, sends up the flares as a public health emergency, which quickly ignites international concern. The disease occurs in only about one in every 200 cases of infection, so for every sick child — and infants and children are the most vulnerable — odds are there that hundreds more unwittingly carrying and spreading the pathogen.

It hides out and multiplies in the human gut, and is excreted into the world through human waste. It can survive in the landscape for a few weeks, and in densely populated areas with little or no sanitation, as is the case in many neighborhoods of Kano, it is carried about by flies and foot traffic. It can seep into the water supply, and it can be spread by coughing or kissing or sharing food or shaking hands. Peak season comes with the annual rains that send it coursing through the city.

Most tellingly, it is in the badlands of Boko Haram, the Islamist extremists of northern Nigeria, along with stretches of the Pakistan and Afghanistan border controlled by the Taliban, where the planet’s last nurseries of wild poliovirus are found: no-go zones where terrorists actively stop vaccine from reaching babies and children.

By last summer, it had been almost three years since the last polio case in Kano state, and for a moment it seemed it might go down in history as the last in all of Nigeria, and that the African region would finally be certified as polio free. Then in July of 2016, a two-year-old girl in northeastern Nigeria became paralyzed, and by August she was confirmed as the first of four polio cases in Borno, a war-torn state east of Kano. Genetic analysis indicated the outbreak had been festering undetected for at least five years, possibly spurred on by the horrific militancy of Boko Haram, which has scattered 1.9 million refugees across the country.

All of the most recent victims were children who had been huddling with their families in crowded, unsanitary camps where they had fled to escape the violent jihadists.

Kano, the capital city of a state bearing the same name, is one of the most populous regions in Africa’s most populous nation. Every day, buses and cars travel the 365-mile route from Maiduguri — ground zero of the Nigerian polio outbreak and the flashpoint of Boko Haram’s ambitions to establish a caliphate — and unload into Kano’s city center. Teams of vaccinators work shifts at the bus stations to meet them and deliver doses to all children under five before they vanish into the homes of relatives or displaced persons camps. It’s a determined effort, but they only have to miss one carrier for it all to come undone — and this is the reason for the spectacle now playing out in this Kano square: It marks the launch of the latest mass campaign to deliver vials of oral vaccine throughout the city, to fortify it against a marauding pathogen poised to ride back into town aboard a ramshackle bus.

Polio has disabled and killed people throughout human history, though until the Industrial Revolution it was largely held in check by the immunity infants acquired from their mothers. The advent of modern sanitation proved advantageous to the poliovirus, in large part because children encountered it later, when their defenses had faded. By the mid-20th century, epidemics of polio terrorized industrialized nations. Stricken children lost the use of their limbs and sometimes their lungs.

At its height in the United States in 1952, around 21,000 cases of paralytic polio were recorded, and many patients were confined to iron lungs to survive. New vaccines were deployed in a blanket campaign beginning in 1955. In two decades, the threat vanished in the wealthy world, only to be found festering and crippling children across the developing world in the 1960s and 70s — and at much higher rates than the West had ever known.

In 1988, inspired by success in wiping out smallpox almost a decade earlier, an audacious international public-private partnership known as the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched with a mission to eradicate polio in just 12 years. Today, 17 years past that deadline, the unrelenting effort has seen the wild poliovirus hunted almost to extinction. The last stand plays out in isolated, incendiary pockets of the planet, where the virus capitalizes on an admixture of politics, faith, and militant conflict.

The ceremony underway in Kano this sweltering morning provides insight into the intricately crafted playbook of the counteroffensive. Center stage in the square, rising from plush armchairs to deliver long speeches, are the state’s deputy governor, Hafiz Abubakar, and the state commissioner for health, Dr. Kabiru Getso. They’re here to show government solidarity with the vaccine campaign. Around them, crammed tight under a makeshift awning — feeble shelter as the temperature nudges past 110-degrees Fahrenheit — are representatives from the World Health Organization (WHO); the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); assorted health apparatchiks paid by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the influential global health philanthropy established by the Microsoft co-founder and his wife; and Rotary International, the global charitable organization, which first began rattling the tin cup for polio across its well-heeled network in the late 1970s. Together with the CDC, they make up the full choir of the GPEI push.

Outranking them all for local clout, though, is the emissary of the Emir of Kano, who swans in and out of the scene shepherded by fawning courtiers and security men in sharp western suits. The support of such traditional leaders, who wield enormous influence across the mainly Muslim north, is imperative to the polio campaign’s success.

A few of the young women who are the foot soldiers of the campaign can be glimpsed in the crowd, but most have already disappeared into the surrounding communities. Their blue veils are printed with the slogan “Lafiyar al’ummarmu hakkin kowa da kowa ne” or “The health of the child is the responsibility of all,” and they are among an estimated 138,000 volunteers who will spend the next four days going house to house, shanty to shanty, and hut to hut, across Nigeria and four other countries in the polio danger zone around Lake Chad. It’s the latest in a calendar of orchestrated pushes to eliminate polio from Africa and the world, and it comes on the heels of another epic vaccination campaign across 13 countries, including Nigeria, just a month earlier.

Meanwhile the only women seated on the official dais are this reporter and another from London. Abubakar welcomes us with a gag along the lines that only mad dogs and journalists would come to the scorching north in April — we’ve been roped into the show. When a half-dozen newborns are presented so the deputy governor can squirt drops of vaccine into their mouths for the cameras, I’m ushered into the local media scrum to take photographs, and to be photographed.

This pageant is not mere grandstanding. Polio vaccinators are hunted, abducted, and killed by extremists in Pakistan and Afghanistan. They have also been targeted in northern Nigeria, including around Kano. As tens of thousands of volunteer vaccinators venture out again today — armed only with clipboards, ice buckets of vaccine, and local knowledge — this square crisply manifests the myriad affiliations that must be painstakingly assembled to support a polio campaign, to mitigate against mistrust around the vaccine, and to keep all of its players safe as they travel the last hard yard.

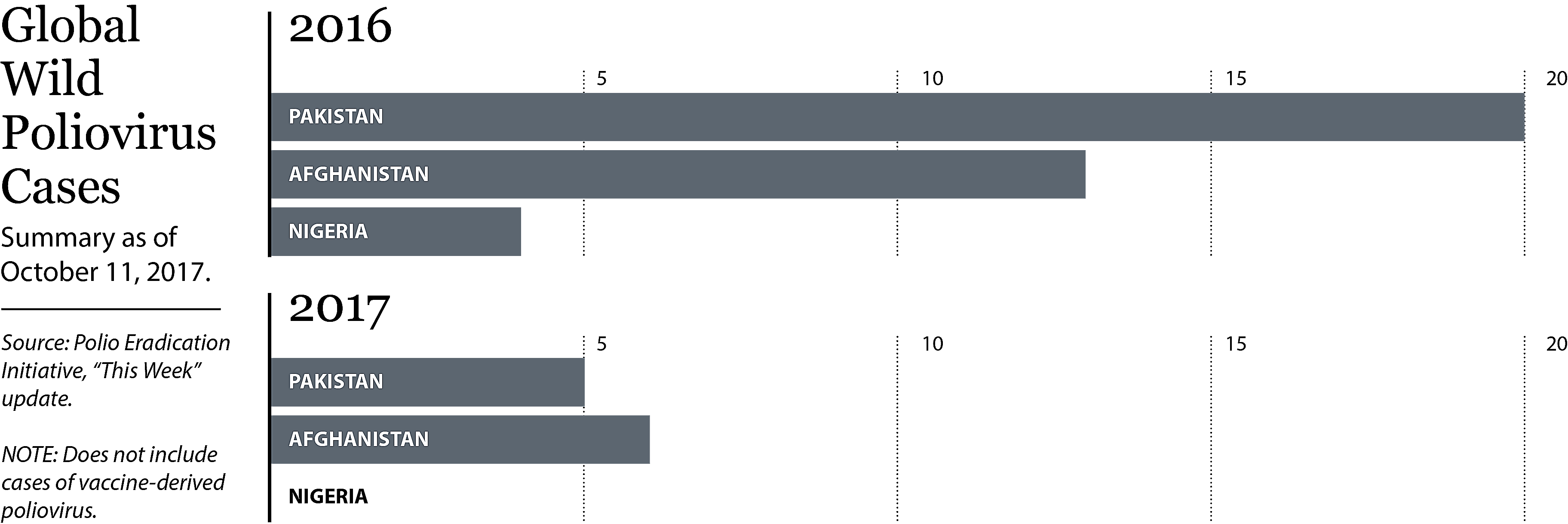

It is hard, indeed. In 1988, there were 350,000 polio cases globally. Some $15 billion later, by 2016, there were just 37. In 2017, there have so far been just 11 alerts of “wild” polio cases worldwide – six in Afghanistan; five in Pakistan; none here in Nigeria, the last of the trifecta of nations where the disease is endemic.

It is the lowest tally ever, stoking cautious hope among the legions of international anti-polio crusaders that 2017 will see the last recorded case of wild poliovirus disease, and that in 2020 the disease will be declared officially eradicated. Tempering that is an outbreak of 47 cases of vaccine-derived polio in Syria, where war has shattered once strong vaccination regimes, allowing weakened live virus excreted by vaccinated children to escape into the unprotected population. Vaccine-derived polio is regarded as a lesser threat than wild virus, but it nonetheless poses a wicked challenge to international health teams, sucking up resources, personnel, and momentum for the last, hard push of the campaign.

Today, it’s costing more than $1 billion a year to hang onto the ground won on polio and, inch by inch, to overcome religious resistance, cultural mistrust, and a backlash within vulnerable communities where the disease has faded from memory and more immediate crises — other diseases, lack of food, political strife — can seem a higher priority than polio vaccine. If the war on polio is to be won, it must run the gamut of all these — as well as the terrorizing resistance of violent men with guns.

The formalities finally over, we are released to our little bus and the care of a half-dozen police guards assigned to go everywhere our media posse goes, tracking the polio campaign as it fans out through the country’s fractious far north over the next few days. Our route will skirt around the powder keg of Borno, which is deemed too dangerous for us to enter.

Sweeping polio out of such dark corners, and from any prospect of wider spread, will require heroic effort and billions more dollars, but the stakes are unmistakably high: WHO has warned that failure to quash the disease in these remote strongholds could, within only a decade, cascade into 200,000 children being paralyzed globally every year.

The officers riding shotgun in the open tray of the police escort vehicle don’t appear to raise a sweat in the blazing sun. Nonetheless they clasp their AK-type rifles with gloves to stop them sliding out of their grip. Sirens cut a route through heavy traffic, chaotic crowds, and herds of goats. We pull up at Kauyen Alu Health Clinic where we’re welcomed by Abbas Ibrahim Musa, whose story we have come to hear.

On the morning of February 8, 2013, at the tail end of a national vaccination drive just like the one we’ve just seen kick off, Musa — a public health officer — was at work here helping volunteers pack their iceboxes with vials for “mop up” day. The women would go back to households where they knew, from their own neighborhood reconnaissance, that they had missed a child. Or to try once more to talk around hardline “non-compliants” — families, or more precisely fathers, refusing vaccine for their children.

The logistics on which global polio eradication relies are expansive and intricate. They require locating children and newborns in crowded slums and remote villages across some of the most impoverished parts of the planet, places where a birth certificate and a street address are unknown luxuries. This miracle must be carried out at least four times for every child, as required for oral vaccine to be effective. The whole enterprise is repeated every few months to capture the next crop of babies.

This strategy has achieved the impossible across the globe — most astonishingly in India, population 1.3 billion and counting, which was declared polio-free in March 2014. But in India, vaccine teams and surveillance monitors didn’t have to navigate war zones, or confront aggressive resistance and accusations that they were the pawns of a Western plot.

The agenda of the gunmen who came to the health center that February morning four years ago is open to speculation, but the consequences for the polio campaign are beyond doubt. Our questions for Musa about that day are initially tentative, mindful of stirring up trauma, but his responses are matter-of-fact, inured by his reality. “I heard a gunshot, and I raised my head up to look, and I saw somebody there holding a gun. Then he fired the gun again … I said ‘Let’s fall to the floor,’ so we all fell to the floor.”

A group of gunmen had overtaken the vaccine team that day, and one was targeting Musa and his colleagues at the health center. “He was saying ‘shoot them … shoot them,” Musa recalled.

At first, he wondered if the national drug law enforcement agency had come, because “we are having a problem with hoodlums coming to smoke Indian hemp within the perimeters of the hospital … until I heard them shout ‘Allahu Akbar,’ and I thought OK, this might be a terrorist.” He waves toward a sparse cubicle where he and his fellow vaccinators huddled. The health center is such in name only — grimy yellow walls, rough furniture, no equipment or medicines to speak of.

Before leaving, the gunmen splashed fuel about the facility and ignited it. “When I tried to sit up, I found that people were lying with me, and I was soaked in blood,” Musa says. Three were shot and wounded that day, and three were shot and killed, he recalls. The dead, he says, were two men and one woman who had just completed her nursing studies. Witnesses said the gunmen came and left on mopeds or motorbikes.

That same morning, a short distance away, gunmen on mopeds attacked another health clinic, where six to eight women vaccinators and at least one man were killed. Media reports are inconsistent about the final death toll — at least one died of injuries in the hospital — and about the sequence of events.

What’s clear is that nobody was charged with the killings, and no culprits were identified — although the wide assumption is that they were linked to the home-grown Nigerian radical insurgency Boko Haram, most infamous abroad for the kidnap of 276 schoolgirls from the north-eastern town of Chibok three years ago. The group has menaced, bombed, shot, and murdered thousands of citizens in Kano and throughout the north since 2009, and another eight vaccinators have been gunned down in Borno state since the 2013 attack, according to a senior Nigerian polio campaign official.

For his part, Musa isn’t convinced that the polio program was the explicit target — he wonders if it was just opportunistic, destabilizing violence. But whatever the objective, the attack shattered progress on vaccinations, and he couldn’t persuade vaccinators to venture back to work for eight months. Some never came back. “Even the first round we conducted, there was this fear among the team members,” he tells me. One woman did her rounds hiding her vaccine carrier inside her hijab, “because she didn’t want to be seen carrying the box,” Musa says.

Today, he has again spent the morning dispatching unprotected young women with vaccine door to door. Do his teams feel safe — are they safe? “Yes, they feel safe,” he answers for them. “We always tell them at the training that they are working to save humanity. And if polio is eradicated, their names will be written in gold as people who helped eradicate polio in Nigeria.”

Every month, former New York Times science editor David Corcoran talks shop with some of the finest science journalists working today. Check out the series here, or find it through iTunes, Google Play, Soundcloud, or any of your favorite podcast apps.

For all his skepticism about the group’s motives, Musa does say that if not for Boko Haram, polio would already be history in Nigeria. Instead it looms as a live threat. He’s part of the firewall authorities and polio officials have constructed to try to stop the poliovirus that has bubbled up in Borno from slipping into Kano. His patch includes one of the city’s biggest bus stations — or motor parks, as the locals call them. He deploys shifts of health workers to try to meet every bus and car, to dose every child and infant before they vanish into the city.

We go with Musa to check in on his team at the bus station. It’s a chaotic market place and transport hub where hard-worn mini-buses and overloaded family cars ferry passengers to and from centers around the country. Motor parks around Kano are favored targets of insurgents, including using suicide bombers. Our police escorts are twitchy, insisting we don’t linger long.

Today there are not the numbers pouring in from Borno as there were at the height of the fighting a couple of years ago. Indeed, we meet one young woman who, with her children, is looking to catch a ride back to the northeast to visit the parents she hasn’t seen for two years due to the insurgency. Her father will meet her, she says, and has told her it is safe now. No buses arrive during our short visit, but Musa says they still come most days.

We go to talk to some of the Borno diaspora at a crowded displaced person’s camp a short drive away. They’ve made the journey looking for what the violence denies them at home: health care, including routine immunizations outlawed by the jihadists’ war against western influence, and freedom to move, buy food, attend school, and go about their daily business without fear. The camp leader, Malam Sani Baga, tells us he arrived two and a half years ago after Boko Haram killed seven of his children. His community survives hand-to-mouth in Kano, begging and selling their labor when they can, waiting until it is safe to go home. Some of the children go to school, some miss out.

Musa does the math on the risks. “Once one child is carrying polio virus, he can transmit to 200 children,” he tells me. “What if 10 children that are coming are carrying polio virus? They are going to share that with how many children? 2,000 children. So that is our fear, that is why, right now, there is a team at the motor park.”

Outside the city, the parched landscape opens to the horizon. Bony cattle with long bows of horns loiter under lonely trees with their human minders. Their manure is piled into neat mounds on the earth, waiting to be sown in with the crops when the rains come. The village of Ungogo feels a long way from the commotion of Kano. The air is clean and the streets are wide and almost entirely empty of vehicles, but they are jam packed with corps of vaccinators and crowds of children.

The polio campaign here is a raucous, earthy counterpoint to the courtly city ceremony. Wandering minstrels pound rhythms on their drums for “Papa Lolo,” his face painted bright blue, jiving and sweating and waggling a luxuriant tail from his super-sized clown bottom. He’s bait, raining candy and sachets of milk powder on joyful, ragged kids materializing from everywhere.

The volunteer vaccinators are local women, most with no skills beyond their community connections and commitment to the campaign. They are paid a small stipend — 10,000 Naira, or roughly $30 per month. The pink drops they administer are the same serum Albert Sabin cooked up in the 1950s from weakened strains of poliovirus. Because it is taken directly into the gut, where poliovirus breeds, it is highly effective. It’s easy to administer and cheap — less than 20 cents a dose.

But there is a catch. This live virus can mutate back into a virulent form and cause vaccine-derived poliovirus, as opposed to naturally occurring or “wild” poliovirus. Last year, there were five cases of vaccine-derived disease recorded — three in Laos, and one each in Nigeria and Pakistan. But this year the number has blown out to 56 — the 47 cases in Syria, and nine in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

It’s the first time polio cases derived from the vaccine have outnumbered those caused by polio itself. Coping with the fallout of this adds to the complexity, and the cost, of the polio endgame. The WHO plans to phase out the oral vaccine, ideally by 2020, and replace it with the injected, inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), first created by Jonas Salk and already routinely used across the developed world. But this shift faces several hurdles in a context like Nigeria. The injected vaccine is more expensive to buy and deliver — the corps of ordinary village vaccinators we see working here will have to be replaced by medically trained teams. Then there is the question of supply — there isn’t enough IPV on the market to vaccinate every child on the planet. And while IPV is highly effective and fully immunized children are protected from polio paralysis, because the injected vaccine does not immunize in the gut, a child who becomes infected with poliovirus could carry the disease for months and continue to spread it through their stool.

For now, until polio is wiped out, live oral vaccine continues to be the workhorse of the global eradication effort. So we follow the blue hijabs as they infiltrate walls of pale earth, surprising women going about their chores inside. They are grilled with a set of questions to determine how many children under five live in the domicile, if they have any visitors, if there are any sick children — particularly any that are having trouble moving their hands or legs? Finally, they are asked for permission to vaccinate any eligible children.

A couple of drops are squeezed into the mouth, and the child’s finger is painted with dark ink. In countries where oral vaccine is used, routine immunization requires one dose of IPV and three doses of oral vaccine. But in Nigeria, this covers only about 30 percent of children. Here and in other polio-endemic and high-risk countries, house-to-house campaigns like the one we are observing occur several times a year to pick up any children who might have missed out. Some kids might get dosed a dozen times before their fifth birthday. As she leaves, the team leader scrawls her report on the outside wall with chalk. Every house bears the fading graffiti of previous polio vaccination visits.

The campaign procession also includes polio survivors on crutches or propelling themselves over the sand using their hands. They display withered limbs and recount their hardships to any parent who hesitates to allow the vaccine. If that doesn’t do the trick, there’s a SWAT team of imams and village leaders — all men — who will be summoned to intervene and talk to hesitant fathers. Mothers rarely need persuading, but they are beholden to the ruling of the household head.

“Before, there were many non-compliants related to religion,” says UNICEF’s Binta Abdulsalam, a dynamic, articulate vaccine evangelist in a rich red hijab. “I’m working for the community, for child survival.” She is the overseer of the campaign in this area, and says vaccine refusal on religious grounds has been drastically reduced. “Anybody who says he will not take this immunization related to religion, we go and sit down with him and discuss and show him it has no harm, and they accept it.”

That compliance was hard won, and this region, not so long ago, was the wellspring of rumors that ran the global eradication program wildly off course.

In 2003, an influential Kano physician, Dr. Ibrahim Datti Ahmed, claimed he had evidence that polio vaccine was laced with “anti-fertility substances,” inflaming local suspicions that the campaign was a western ploy to curb Muslim population growth. Fears were first fanned by sensational accusations — then in the courts — that sick children from Kano’s slums had died or been injured during an unlicensed trial by Pfizer of a drug to combat meningitis.

That case was ultimately settled in 2009 by the pharmaceutical giant for $75 million, with Pfizer stating that it was the disease, not the drugs, that was to blame for the casualties. But the damage was done. Polio programs were shuttered across five states in impoverished northern Nigeria — all Muslim majorities governed by Sharia law. The boycott lasted longest in Kano, where it endured until independent testing assured local leaders of the vaccine’s safety, and the governor — who had previously declared it “the lesser of two evils” to sacrifice even 10 children to polio than to render girls infertile — was persuaded to revive the campaign by having his daughter publicly vaccinated.

By then, though, the virus had been given time to gain ground. The year before the boycott, there had been just 202 cases of polio across the country. In Kano state alone in 2004, before the ban was lifted in September, 491 children were paralyzed. The virus was spread across the country by legions of unwitting carriers, spiking at 1,143 cases nationally in 2006. Genetic analysis tracked Nigerian strains jumping borders into a dozen previously polio-free countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The outbreak reached 20 countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia and caused 80 percent of the world’s cases of polio paralysis at that time. The cost to regain control: Roughly half a billion dollars, according to a 2009 analysis by the Global Health and Foreign Policy Initiative.

Conspiracy theories about vaccine programs reignited in 2011 after reports emerged, and the CIA eventually admitted, that it had staged a Hepatitis B vaccination program to try to collect DNA and pinpoint Osama Bin Laden’s family hideout in Pakistan. Dozens of polio workers have since been targeted and slain by the Taliban in that country. At the time, shattered public health experts said they feared the fallout would be devastating, with one leading U.S. expert saying it could postpone polio eradication by 20 years, and lead to 100,000 more cases. Recent analysis shows polio rates increasing in Pakistan after 2013, and link this to the CIA operation.

In Kano, the years of effort to reinforce support for vaccinations, and the systems to deliver them, appear to have held. If not for Borno and Boko Haram, Nigeria would now have been free of polio for three years. It’s an astonishing achievement given that in 2012, the country accounted for more than half of all polio cases worldwide.

The importance, and fragility, of all that work comes into focus with an introduction to Ismail, a teenage boy who scoots around Ungogo in a low tricycle, his wasted legs tucked under him. He loiters on the fringe of the polio parade, watching the resources being thrown into making sure no more children become like him. He blames his parents, he says, for not giving him the vaccine as a child. But his age indicates he is very likely a casualty of the vaccine boycott in the early 2000s, or of its lingering aftermath. Perhaps they had no choice.

Back in the Kano city center, we go to watch a fast and furious game of para-soccer. The players’ muscular, super-fit torsos are strapped to skateboards, their shriveled legs knotted under them. They skim fearlessly across an asphalt playing surface, some propelling themselves with bare hands, some with flip-flops threaded through their fingers for flimsy protection. The most able-bodies are the goalies, wobbling on spindly, fragile legs.

Kano has just won the national para-soccer league championship. The state’s history of vaccine resistance means it corners the market on fit young men (and women, though they don’t get to play) debilitated by polio. “The fact that 70 percent of all para-soccer players at this competition are from Kano has helped the growth of the game in our state,” the jubilant coach told local media after his team won the national titles for the second year. “We are the home of para-soccer.”

On the sidelines, a huddle of crippled younger boys watch their heroes play from their low cycle chairs — more casualties of the boycott. Kano is likely doomed to retain its para-soccer advantage for some years to come.

During a field visit to Kandahar, Afghanistan, a few years back, communicable diseases specialist Dr. Mike Toole met the provincial governor to discuss getting vaccine into Taliban controlled areas. “He got out his mobile phone and called the local Taliban commander, who spoke English, and handed the phone to me,” Toole recalls. “I asked him about his attitude to polio [immunization]. He said ‘I’m all for it — I don’t want my kids dying.’” The Afghanistan Taliban has put out statements supporting the polio campaign and giving vaccination workers safe access through Taliban areas, though these don’t apply in all insurgent areas.

Toole, an Australian, is a disaster zone veteran and served on the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) set up in 2010 to oversee the global polio eradication program until earlier this year, when the board was reconstituted in anticipation of polio being eradicated and a shift in footing to a post-polio world.

He recounts the Kandahar story when we meet in Melbourne. He’s trying to illustrate a fraught distinction between mad and bad, or bad and badder. “I don’t want to say the Afghan Taliban is nice. They’re not nice,” he says. But some in their ranks have experience of institutions, of governance, and respect fatwas (formal rulings on Islamic law,) supporting polio vaccines written by Muslim clerics. “These others — the Pakistan Taliban, Boko Haram, Al-Shabaab in Somalia,” he says as he shakes his head. “Just crazy.”

Since the polio program began nearly three decades ago, at least four “end-game” deadlines have come and gone. Crucibles of disease continue to incubate in just three geographically tight enclaves where militant extremists prevent vaccine reaching children. If the pathogen is carried out of these reservoirs into vulnerable landscapes, they have a proven capacity to ignite wildfires. “It’s all about conflict,” says Toole. A 2016 study tracking outbreaks of wild poliovirus showed it capitalizing on war and instability, including its reemergence in previously polio-free countries like Syria.

There are populations in secure, even wealthy nations where anti-vaccination sentiment, fatigue, or complacency — especially in higher-socio-economic demographics — has eroded immunization levels to the point they are vulnerable to an escapee bug.

In 2013, there was a “silent” poliovirus outbreak in Israel — “it was only detected in sewage — no cases,” Toole says, noting that cities throughout the world routinely trawl their collective waste for poliovirus. Laboratory analysis indicated this bug had come out of Pakistan. It didn’t gain purchase in Israel, likely because immunization rates there are so high. But there’s a lot of traffic between Israel and Melbourne’s Jewish community, and vaccine coverage in that community’s epicenter is only around 85 to 90 percent, which had Toole concerned. “I was worried that a kid, an unvaccinated kid, could go to Israel, and be exposed to a kid who had the virus but wasn’t paralyzed.”

Toole briefed health authorities in the Australian state of Victoria on the prospect. “It didn’t happen,” he says. But it could have.

Maintaining scrupulous surveillance — not just for active disease, but sampling and testing water supply and sewage, wading into lakes and rivers of shit with buckets looking for poliovirus, is critical. The IMB on which Toole served has advocated for the reinstatement of a publicly prominent “Red List” of 32 nations vulnerable to polio outbreaks due to low immunity, weak surveillance, or low infrastructure. The recent cluster in northeast Nigeria, which genetic analysis revealed had been circulating undetected since at least 2011, provides a sobering reminder of the potential of an outbreak to fester under the radar. “Every time I get an email from these countries,” Toole says, “my heart drops.”

Is he hopeful that eradication will be achieved? Toole answers carefully. It is, he says “harder and harder” to maintain optimism. The IMB of which he was part published its last report in August 2016, just as the latest Nigerian cases emerged. The board’s focus was on the formidable challenge of cleaning out reservoirs of infection in Pakistan and Afghanistan. “The hour is getting late,” the board warned.

“It’s huge, it’s like a war,” says Toole. “It just has to be organized right down to the local level and tailored for each community.”

He pointed to Borno state, where more than 100 of the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram remain in captivity. “What capacity do they have to continually get in there and continually vaccinate those kids?” Toole asks. “That’s what dents your optimism.”

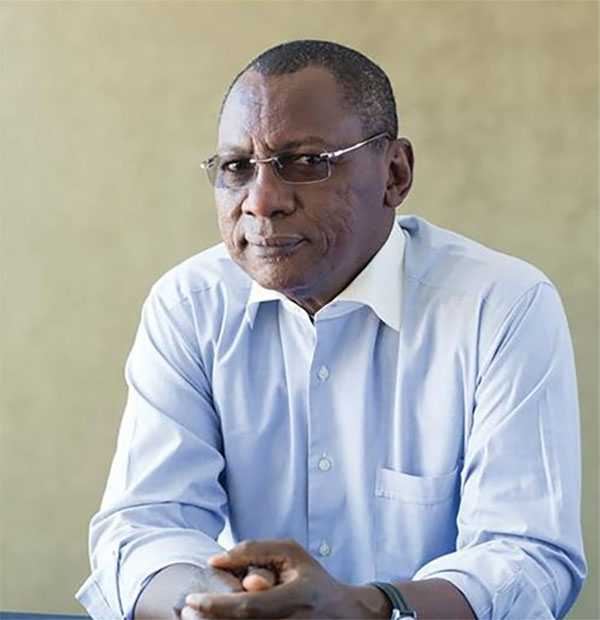

Dr. Abdulrahman Tunji Funsho, an eloquent retired cardiologist and Rotarian, is one of the leaders of Nigeria’s anti-polio push. We meet in the nerve center of the operation he chairs, the Rotary’s Nigeria Polioplus Committee, in Lagos, under an honor board of old, mostly white men, venerated for their services to Rotary and to the polio cause.

He introduces the portraits one by one — “and that’s the actual doyen who started the whole idea of championing the cause of polio, Bill Sergeant. He’s late now,” Funsho says. Rotarians have raised more than $1 billion out of $15.2 billion contributed to GPEI programs over the last 30 years. They are the second biggest private donors after the American billionaire philanthropists Bill and Melinda Gates, who have put in $3.1 billion over that time.

There’s something incongruous about the notion that a global network of civic-minded business and professional people, conducting jocular three-course lunches in suburban eateries, are bankrolling the operation Funsho describes. Who knew accountants could be so subversive?

But to those on the ground, the origin of the money is far less important than the fact that it is there, and Funsho speaks to a slideshow of maps showing the flashpoints of disease and insecurity, tracking the advance and retreat of Boko Haram through the northeast. “In the days where Boko Haram were controlling certain territories, WHO was literally smuggling vaccines,” he tells me, “using collaborators at the risk of their lives who would take vaccines and go and immunize children surreptitiously under the very nose of Boko Haram.”

Dr. Abdulrahman Tunji Funsho, a retired cardiologist and Rotarian, is one of the leaders of Nigeria’s anti-polio push. “In the days where Boko Haram were controlling certain territories,” he said, “WHO was literally smuggling vaccines.”

Visual: Rotary International

The red-painted no-go zones have contracted in the past year as the army’s campaign against Boko Haram has gained ground, and vaccinators have reached into newly liberated areas. “The army was able to push them literally just to these two local government areas,” Funsho says, gesturing to the screen. The success of government forces came with a mass exodus of newly liberated people coming to the center of the capital of Borno state, Maiduguri, where poliovirus transmission risk is measurably higher. The slide shows four red pins clustered in the top right corner of Nigeria. “It is in this kind of situation that those four cases were picked up, inside IDP camps,” Funsho says.

Just how many people are still trapped inside the Boko Haram-controlled red zones is anyone’s guess, he says. Local militias carrying vaccine are escorted into the most unsafe hotspots by soldiers, and military medical units do opportunistic immunization hits where they can. Troops scope out opportunities to launch hit and run vaccination sorties. “If we get a call from security saying ‘this area is secure for two days if you want to come in and immunize,’” Funsho says, “we work in concert with them.”

He and other campaign leaders say that their best option would be to negotiate with the insurgents — in other words, to emulate what Mike Toole helped to organize in Afghanistan: negotiate ceasefires with local warlords or other leaders, however temporary, to allow immunizers access. They say that this ambition has always been out of reach because Boko Haram doesn’t have an identifiable leadership with whom to negotiate.

Recent events signal that maybe that is changing. In early May (shortly after our interview), news broke that 82 of the kidnapped Chibok schoolgirls had been released after lengthy negotiations between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram via the international Red Cross and the Swiss government. I contacted UNICEF officials to ask if that has cracked open any prospects of negotiating a polio ceasefire. “The program seeks to take advantage of any opportunity to reach unprotected children in inaccessible areas with polio vaccine,” was the careful response from Rod Curtis, a UNICEF spokesman.

In the absence of some breakthrough in negotiations with the militants, intelligence-gathering is critical: “We have a system of informants — taxi drivers, bus drivers, patent medicine sellers, traditional birth attendants, those likely to come in contact with families and children below the age of five,” Funsho explains. “They are trained to recognize any case of paralysis.”

Surveillance officers pick up the trail, looking not just for polio, but for measles, meningitis, other communicable diseases. They collect stool samples from suspect polio cases which are analyzed in one of two laboratories in Nigeria. If positive, the samples are sent on to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratories in Atlanta for confirmation, typing, and genetic clues as to whether the viral strains are local or imported, new or old.

The networks nurtured by the polio campaign proved their lifesaving worth in another context in 2014, when Nigeria confronted and efficiently swatted out what could have been a catastrophic Ebola wildfire. “The world really was on the brink of an abyss,” Dr. Thomas Frieden, the outgoing director of the CDC, told a gathering in Washington D.C. last December. “There was the possibility that Ebola would get out of control in Lagos, Nigeria. It had already been spreading for more than a week. The initial response of the Nigerian authorities was not effective, and then Nigeria had the wisdom to put the polio eradication infrastructure in place to manage the response. And they very rapidly controlled it.”

Resources and personnel borrowed from the polio campaign helped map every Ebola case and track every potential contact, conducting 18,500 visits with individuals to check for symptoms, and snuffing out the outbreak. This success anticipates one of the key selling points for continuing investment in polio — that it will yield networks and expertise with the capacity to deliver incalculable health and economic dividends long after polio is history. Frieden told his Washington audience that the cost of a pandemic is around $6 trillion, while the annual cost per person of protection against disease threats is around 65 cents. A 2010 study argued that eradication would generate $40 billion to $50 billion in net benefits by 2035. “Global health security is smart spending,” Frieden said.

Nonetheless, there’s anxiety about whether the money and wherewithal required to make polio eradication a reality will continue to be forthcoming from exhausted donors and ambivalent governments. Australia has walked back its commitment in recent years, and the Gates Foundation has warned that 30 percent cuts to U.S. foreign aid proposed by the administration of President Donald J. Trump could allow polio to make a comeback. (A bipartisan task force of former State, USAID, and congressional staffers is reportedly pushing back against the cuts.)

“If Trump pulls the plug on polio, [the campaign] will probably die,” Mike Toole says. The U.S. government has been one of the most generous supporters, providing more than $2.9 billion over the past three decades. In August, the U.K. Government stepped up with a pledge of about $130 million.

Dr. Funsho discusses the re-emergence of wild poliovirus in Nigeria last year — just when it looked like the country might be polio free.

In June, Funsho was among more than 30,000 Rotarians who gathered in Atlanta for an international convention designed to plot strategy and replenish the war chest for what they hope, again, will be the endgame. Bill Gates delivered the keynote speech, joining other gathered donors in pledging more than $1 billion to continue the battle against polio. Gates pledged a two-to-one match on Rotary International’s goal of raising $50 million a year for the next three years — a deal that would deliver $450 million. “Polio is the thing I spend the most time on,” Gates told the gathered crowd. “Every day I look at my email to see if we have a new case. I’m very inspired to be part of this. I’m also very humbled.”

For all of the pledging, though, the sum result is that there is still an estimated $300 million shortfall in the funds required to achieve eradication by 2020, and insidious challenges foment even within the ranks of true believers. “There is fatigue at every level,” says Funsho. “There is fatigue at the level of donors, there is fatigue at the level of Rotarians, and there is fatigue at the level of the government.”

Indeed, experts warn that after 30 years of effort, complacency is on par with insecurity as the most powerful threats to the ambition of eradication. Maintaining momentum for an almost vanished disease is a tough ask, especially given the caseloads of other diseases rampant inside the same communities where the endgame with polio is being fought — tuberculosis, including antibiotic resistant varieties, as well as malaria and HIV/Aids. For the 2016-2017 financial year, polio accounted for about $895 million of WHO spending. By comparison, all the other communicable diseases combined — TB, HIV, malaria and various tropical diseases — cost $765 million.

I ask Funsho if he’s ever concerned that after all this, after three decades of effort, eradication of the virus will prove an unachievable goal, or that all of his efforts, and those of the armies of immunizers toiling in the virus’ last strongholds, could all be undone by the villainy of outlaws in three remote corners of the planet. But Funsho regards these notions as unthinkable.

“My optimism is not born out of just an emotional attachment to polio eradication. It is also born out of technical analysis by WHO and the Gates Foundation,” he tells me.

“We’ve done it in Sudan, which is a conflict area,” Funsho continues. “We’ve done it in Central African Republic, which is continuously a conflict area. So we have the technical expertise to overcome the challenges of reaching children in conflict areas. We’re quite confident. It is just a matter of time till we do it.”

On the last day of the campaign, we’re in the city of Katsina, just under the border with Niger and in the next state over from Kano. We shadow another vaccination team through winding alleys between close houses, watchful police guards striding in a phalanx around us. We pick a careful route through knots of curious onlookers and across open drains carrying rubbish and human waste.

We follow team supervisor Rhoda Samson, coolly regal in swathes of raucous orange and red cotton, as she powers through cloying heat and shadowy doorways. She’s a force of nature, a vaccine guerilla fighter, sweet-talking mothers and cuddling babies and hard-selling vaccine. She beats a purposeful path to a hard-core “non-compliant” household, as the graffiti of thwarted visits on the wall outside attests. Her vaccinators have been turned back here many times. Inside the stifling room are a half-dozen women and a newborn baby boy. The mother hastily pulls on her veil as vaccinators and journalists — one of them a man — pour through her door. “Bamaso,” says the mother, Amina Ali. “We don’t want,” Samson translates.

She doesn’t want her children immunized because her husband doesn’t want it. “She says when the husband refused, and has not offended God, she also has refused. She says that the vaccination of polio is not food. So the husband says since the government can’t provide food, he will not accept immunizing.”

One of the burdens of success of the polio program is that it has retreated so far behind the other urgent concerns preoccupying impoverished parents that they become resentful of the effort being ploughed into what seems the least of their problems. Some enterprising communities seize on the polio priority to barter vaccinating their children against other urgent needs, like a water pump, or a road, or a school, even outside mediation in local political disputes.

Her husband, Ali Zaki, suddenly materializes at the doorway. He’s not happy to find his home besieged. For a moment, things threaten to get ugly. But Samson jiggles his baby and talks rapidly at him in Hausa, gently chastising, smiling, and cajoling. The father glimpses an opportunity to shake us down for a contribution toward the naming ceremony for his baby — a small price to pay on the road to polio’s oblivion. He responds gruffly and Samson squeals, as do the other women in the room, and they dance about with delight. “He says they believe in God, God is the one who does medicine for everyone,” Samson explains. “Since we have come, we should vaccinate the child … God will not allow any evil to befall his children.”

The scene draws a crowd and our police are anxious to get us out. We linger just long enough to see the vaccine squeezed into the unnamed infant’s mouth, and we’re flanked at a fast clip back to the waiting bus, frog-marched across a reality ripe for occupation by invisible foes — human and viral.

In the months to come, the blue hijabs will have to return at least three more times, run this hostile front line unescorted and unarmed, to ensure the unnamed baby boy gets his requisite doses. Every success a step toward so-called “herd immunity” — the magic moment when the proportion of vaccinated population confers protection on the whole. As Rotary’s Dr. Funsho explained: “That is where the end game is going to be. If you are able to ensure that 90, 95 percent of the children are immunized, then the polio virus will not find anywhere to settle and multiply. That is the ultimate hope, doing that.”

Hundreds of miles away and a week earlier, as the journey began in the heaving commercial center of Lagos, I had asked Dr. Abidoye Sunday, coordinator of World Health Organization activities in Lagos state, about the scale of the security challenge. He had just walked us through the gamut of the technical challenges — from dispatching teams with buckets and rubber boots to collect sewage samples from filthy rivers, to maintaining cold-chain integrity for samples and vaccines, to organizing, mobilizing and coordinating the tens of thousands of individuals who make up the polio battalions, to tracking and monitoring individual cases across this vast nation. He has, along the way, recounted the extraordinary story of how these networks saved Nigeria, and possibly the world, from Ebola.

Imagine a pyramid, he says. At the top of it are the commanders, and with every layer the fighters get closer and closer to the community. At the base, you have vast networks of community coordinators, informants, volunteers. They work to conquer insecurity through peace.

“They put their life on the line by going into the lion’s den,” Sunday told me. “I think we are doing our best to ensure that even where you think there is security challenge, thank God for what has happened now. People are laying [down] their lives.

“That,” he added, “is what I want to tell you.”

Logistical assistance for this story was provided in part by Results.org, a nonprofit global health advocacy organization. On-the-ground security was arranged in cooperation with UNICEF.

Jo Chandler is an award-winning freelance journalist, author, editor, and educator based in Melbourne, Australia. She was previously a long-time reporter for The Age newspaper in Melbourne, and was a regular contributor to The Sydney Morning Herald and Good Weekend magazine. She has reported from across sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, rural and remote Australia, Antarctica, and Afghanistan.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Great article

Well captured and educative,it’s need to be translated into the local language if possible, it’s really exciting.

Kudos to Jo Chandler for painting a nearly perfect (though rosy) picture of what is really happening on the ground.

I worked on the front lines of polio eradication in Africa for decades. This is a superb account, by far the best I have seen, of that global effort.