Science and Chinese Somatization

Just after lunchtime, on a blistering summer day in Washington D.C., cultural psychologist Yulia Chentsova-Dutton is showing me the stars. They’re on her computer screen at Georgetown University, and labelled disturbingly: insomnia, anhedonia, headache, social withdrawal, chronic pain, and more. Each star represents a somatic or emotional sensation linked to depression.

Chentsova-Dutton’s father was an astronomer. She’s found a way to use what he studied, the night sky, to understand her own research: how culture can influence the way we feel and express emotion. If you look up, there are thousands of stars, she says. You can’t possibly take them all in. So, each culture has invented schemas to remember them by, constellations. She pushes a button, and several of the depression stars are connected by a thin yellow line.

“This is depression according the DSM,” she says, referring to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. “This,” she says, pushing another button, “is a Chinese model of depression.”

The constellation changes, morphing into a different shape. New stars pop up, most having to do with the body: dizziness, fatigue, loss of energy. Chentsova-Dutton and her colleagues have been comparing these two constellations — of Chinese and Western emotion — for years, trying to explain a long-standing assumption about Chinese culture.

Since the 1980s, cultural psychologists had been finding that, in a variety of empirically demonstrable ways, Chinese people tend to express their feelings, particularly psychological distress, through their bodies — a process known as somatization. I had first encountered this concept while researching a story about my own family connection to the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the curious idea that psychological trauma might be able to pass from one generation to the next — a scientifically tenuous notion, but one that has generated increasing study among psychologists and, more recently, geneticists.

“It has become this one finding from culture and mental health research that has filtered its way down to conventional practice,” Chentsova-Dutton’s collaborator, Andrew Ryder — a cultural psychologist at Concordia University in Canada — told me. “There’s the way people express depression, which is to have a depressed mood. And then there’s what Chinese people do, which is different.”

After I had first learned about Chinese somatization, I began peering through the older literature, but couldn’t find an explanation I felt satisfied with. Ryder said a similar dissatisfaction launched his and Chentsova-Dutton’s research in this area. “You had people writing about how the Chinese are less sophisticated people,” Ryder said. “In the past, people said that the Chinese don’t express emotions the right way. They do it in a kind of immature way.”

Even after rejecting that explanation, Ryder didn’t find another that was more convincing. Some researchers said that it wasn’t the people who were psychologically immature, but the language. They claimed there was no vocabulary for talking about emotions. “Looking back now on these papers, it’s almost unintentionally hilarious,” Ryder said. “What language did they put at the top? It’s English. And the person writing it is at Oxford or University of London, a very English guy.”

And yet, some recent work has continued to show that the Chinese exhibit comparatively more somatic symptoms than other cultures. In 2000, Shirley Yen and her colleagues from Duke University found more somatic symptoms among Chinese students seeking counseling. In 2001, Gordon Parker, at The University of New South Wales, compared depressed Malaysian Chinese with depressed Euro-Australians. He found that the Chinese reported physical complaints more often on their questionnaires, while the Euro-Australians group more frequently reported states of mind and mood. In a follow-up study in Australian primary care settings, they found that the more Chinese-Australians became acclimated to Australian society, the more they reported psychological rather than somatic symptoms.

In 2004, a study spearheaded by the Depression Clinical and Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital found that 76 percent of depressed Chinese Americans interviewed in a primary care setting described mostly physical symptoms. “The results suggest that many Chinese Americans do not consider depressed mood a symptom to report to their physicians,” the authors wrote, “and many are unfamiliar with depression as a treatable psychiatric disorder.”

Other work has yielded more complicated results. A follow-up by Yen found that a Chinese student sample reported less somatic symptoms compared with Chinese American and Euro-American student samples, leading the researchers to conclude it was the role as a patient, and not intrinsic “Chinese-ness,” that led to an emphasis on the body. In 2004, another study from Parker revealed that if Chinese patients were carefully questioned about psychological symptoms, they would offer them — perhaps the Chinese simply didn’t do it on their own.

In 2008, Ryder led his own study, comparing clinical outpatients from Hunan Medical University in China to ones from the Center for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto. He found that both sets of patients had a mixture of psychological and somatic complaints, but the Canadians did significantly report more psychological ones. In follow-up work using the same data from his 2008 research, Ryder found that while the Chinese reported somatic symptoms of depression, it was the Euro-Canadians who emphasized bodily symptoms when it came to anxiety.

For all the cross-cutting results, however, Ryder and other researchers remain convinced that the human experience of depression — and really, of all mental states — is culturally shaped, at least in part, and that the Chinese do tend to more often emphasize physical, rather than emotional or mental states.

“The big debate is becoming, why is this happening?” Ryder said. “I think there are two sides, and I don’t think this has been fully resolved yet. One picture of it is almost a strategic answer, which is that Chinese people are choosing to talk about the somatic symptoms, and choosing not to talk about the psychological symptoms. The other approach is to say, maybe the Chinese are emphasizing somatic symptoms because in fact the somatic experience really is more salient to those people. They’re reporting more sleep problems because they’re having more sleep problems. They’re reporting more pain because they’re experiencing more pain. I think it’s a more interesting possibility. It’s also a lot more controversial.”

My mother was born in China in 1961 and lived there until moving in 1980 to the United States, where she met my father — an American of mixed Caucasian heritage. I tend to think of myself as racially and culturally ambiguous, but as I gazed at Chentsova-Dutton’s constellation of Chinese depression, I couldn’t help but wonder: Is this that how I feel my own emotions, too?

Do I “feel” like a Chinese person?

In 1980, the Minister of Health of China told Arthur Kleinman, a visiting psychiatrist and anthropologist, that there was no mental illness in China. “I knew this was a crock of nonsense,” Kleinman said. “But it was astonishing hearing it anyway.”

As odd as it was, there was some data to back up his claim. The Global Burden of Disease project had reported a 2.3 percent depression rate in China, compared to 10.3 percent in the U.S. Another survey found the lifetime depression rate was only 1.5 percent in Taiwan.

If the Chinese were somehow being spared from depression, they were not from another disorder, called neurasthenia. In the 1980s and 1990s when those mental health surveys were conducted, somewhere between 80 and 90 percent of Chinese psychiatric outpatients were being diagnosed with it. In the outpatient clinic of the Hunan Medical College that Kleinman traveled to, neurasthenia was the most common diagnosis given to neurotic patients. Kleinman, who taught and worked at Harvard and the University of Washington, had never seen the diagnosis given in his clinics.

The American neurologist George Miller Beard first popularized the term “neurasthenia” in the late 19th century.

Visual via Wikimedia.

Visual: Wikimedia

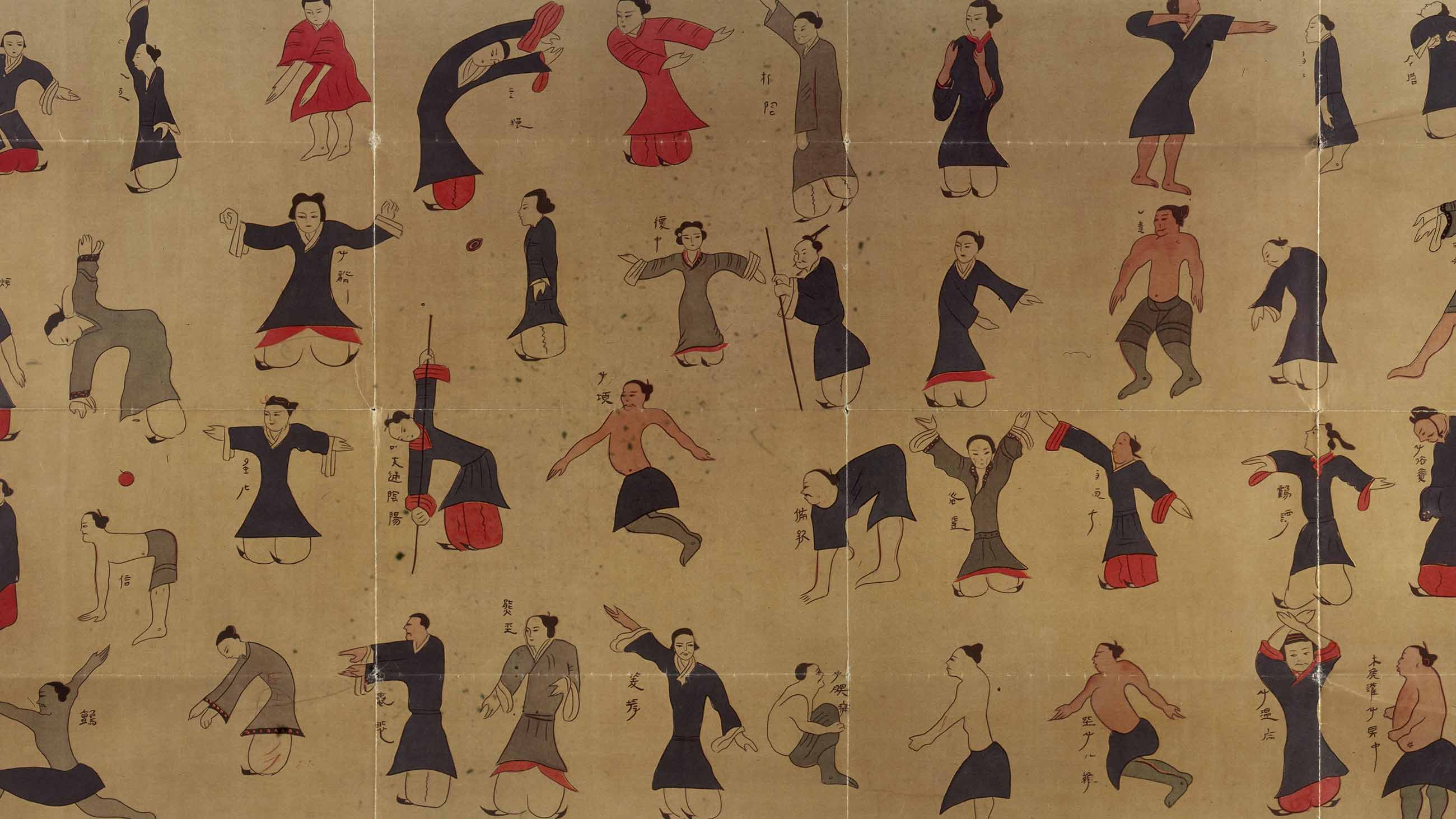

Neurasthenia, first described in 1869 by George Miller Beard, encompasses over 70 symptoms, including weakness, fatigue, memory loss, dizziness, headache, insomnia, and chronic pain. But by the 1940s in the U.S., practitioners were questioning its validity. It eventually fell to the wayside with other too-vague syndromes, like hysteria, which represented a cluster of symptoms rather than a specific pathology. But as neurasthenia was fading away in the U.S., psychoanalysts elsewhere were embracing the term “somatization” — from the Greek “soma,” or body. They thought of it as a primitive defense mechanism, a way that an anxiety or fear buried in the subconscious could break through to the conscious world. And they were increasingly associating it with the Chinese.

Kleinman, working in Hunan, felt there was something more complex going on. In a now classic study in cross-cultural psychiatry, he examined 100 patients from the outpatient clinic at the medical college. Through lengthy interviews and diagnostic testing, he determined that 87 percent of them were actually suffering from depression, and could be treated with antidepressants — even though they had come to the clinic complaining of bodily symptoms and didn’t report depressed moods.

China was a recovering nation, fresh out of the terror of the Cultural Revolution. Kleinman believed that the Chinese didn’t feel safe enough to express their emotions, which could be interpreted as criticism of the government. Instead, they intentionally complained of headaches or pains, a cry for help that was free of political interpretation. His findings sent ripples across Chinese psychiatric communities.

It was a study authored by an American at a time when China was adjusting to a drastic change from Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping, wrote Sing Lee, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Hong Kong. But it also implied something else: that the Chinese were not reading their feelings accurately. The study, Lee continued, insinuated that they had flagrantly missed patients with major depression.

I didn’t know what neurasthenia or Chinese somatization was when I had my first dizzy spell in 2012. After almost failing out of undergraduate school because of anxiety, I put my life on hold to travel and work on farms in Europe. One day, a strange feeling washed over me, like the inside of my head was spinning. I returned to New York, and the dizziness worsened. When I started to feel numbness and tingling in my fingertips and toes, I saw a neurologist who ordered an MRI.

My doctor pulled out my brain scans and declared them, “perfectly normal.” Then, he kindly looked me over and handed me a prescription for SSRIs, the common medication for depression.

This immediately became a joke among my friends: that I had gone to see a brain doctor and he gave me antidepressants instead. I laughed too, but I was puzzled. I never filled the prescription, but continued to get automated messages from CVS, telling me that my SSRIs were ready to be picked up; a robot voice telling me that what I was feeling wasn’t real.

I repeatedly cast back to these experiences while talking to Chentsova-Dutton and Ryder, who said they wanted to rewrite the various outdated theories claiming that the Chinese were too “immature” to feel their true emotions. But they also said they didn’t want to ignore something that their work and the work of others has continued to show: The way the Chinese process and attend to their emotions might actually be different. Part of rewriting the past, in other words, meant learning that different doesn’t mean bad.

“Your cultural context just tells you what is important to pay attention to,” Chentsova-Dutton said. “Usually when you develop depression, you are hit with so many changes in your mind. You’re thinking differently, you’re feeling differently. You’re essentially looking for some sort of explanation in your cultural environment, and if you happen to be in China and people around you talk about neurasthenia, they will tell you what is important to pay attention to.”

Just like she learned the Orion constellation from her father, a Chinese kid could have used the same stars to see a different shape: the White Tiger of the West. In her current experiments in collaboration with Ryder, Chentsova-Dutton is bringing Chinese and American students into her lab and putting their emotional constellations to the test. In their most recent study, which is still under review, the team showed Chinese and European-American young women a sad animated, wordless film. While watching the film, the women had their physiological activity measured, their facial expressions recorded, and they filled out self-reports.

Chentsova-Dutton found that the Chinese women reported more bodily sensations. They said their heartbeat and breathing changed, they noticed goosebumps, and body temperature shifts. Both groups reported that they felt sadness, but the Chinese women also reported some positive feelings. While the movie was sad, they appreciated the beauty of the illustrations, for example.

Chentsova-Dutton said it reminded her of an ancient Chinese fable, from the Taoist tradition, about a farmer and his horse. One day the horse runs away, and the farmer’s neighbor says, “I’m sorry about your horse, that’s bad that he ran away.” The farmer replies, “Who knows what’s good or bad?” The next day the horse returns with a dozen feral horses, and the neighbor says, “What good fortune!” The farmer says, “Who knows what’s good or bad?” And on, and on. The moral is that with each fortune comes a little misery, and vice versa. Nothing is purely good, or purely bad; the classic yin yang model. Chentsova-Dutton’s participants, watching the sad film, were exhibiting this lesson, or what she calls a cultural script. Though thousands of years old, it was influencing the way they experienced their emotions and, also, their bodies.

When Chentsova-Dutton looked at the actual bodily changes in her study subjects, there were no differences in heart rate, perspiration on the skin, or how they were breathing. So, were those sensations “real?” Was my dizziness “real?” Chentsova-Dutton says it depends on what you think is real. There wasn’t something “real” happening in the body, she says. But she doesn’t think her subjects were faking it, or feeling it strategically. She thinks they were genuinely feeling sensations that were coming instead from their brains, which is very real.

It may be that the constellations they’ve been taught include more stars on the body. In America, we’re taught to monitor and pay attention to our emotions. They are our brightest stars, the points that tell the story of “us.” In other countries, those stars don’t shine as bright. The outward contexts matter more, other people, your family, and your body.

What’s also real is the takeaway message: Just because the Chinese were feeling physical sensations did not mean their emotional experiences were dampened or being replaced by the bodily sensations. In fact, Chentsova-Dutton thinks their findings turn the previous Euro-centric theories on their head. If anything, the Chinese were showing a more complex response than the Americans.

“When you directly ask these Chinese women, they know they’re feeling sad,” Chentsova-Dutton said. “But they’re also having a far more nuanced reaction and in the same amount of time that is provided to everyone else.”

If a Taoist fable could change the types and variety of emotions people felt, could such cultural scripts also be changing our brains? In an emerging field called cultural neuroscience, that answer appears to be yes. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a cultural neuroscientist at USC, is currently completing a five-year NSF grant to figure out how culture and our environments shape our brains, and our perceptions of ourselves.

When I found Immordino-Yang’s work, I was drawn to it for a selfish reason: Immordino-Yang was married to a Chinese-American man, and her kids were bi-cultural, like me. One of her studies included a bi-cultural group, and I was eager to ask her: how did I know how I felt? Do I feel like a Chinese person or an American?

In that research she looked at three groups: American USC students, English-speaking second-generation East-Asian USC students, and Chinese students at Beijing Normal University. When she looked at how their neural activity corresponded to their emotional experiences — what they were feeling in the moment — she found “very systematic cultural differences,” in their anterior insulas, the part of the brain that maps visceral states and makes us aware of our feelings. Her findings showed that activity in different parts of the insula was associated with feeling strength depending on what culture a participant was from. And, for the bi-culturals, or second-generation Chinese, in the study, Immordino-Yang found that their brain results fell somewhere in between the full Chinese and full Americans.

When Immordino-Yang and I connect on Skype to talk it over, she tells me that she firmly believes, and her work continues to show, that our biological legacy is intertwined with our cultural one. The ways our brains are wired and develop is shaped by the culture in which we are raised. The answer of “how I feel,” could only be answered by my specific past.

Jeanne Tsai, a cultural psychologist at Stanford University, who has been studying emotion and culture in East Asians for over 25 years, has looked for where that contextual information comes from. She’s examined children’s story books in both the U.S. and Taiwan, the types of smiles that leaders show in their official photos, and images in people’s social media. Among other things, she’s found that European Americans show much more animated smiles.

From her work, she says that American and European culture value excited and high arousal states, compared to Eastern cultures that value calm and stoic ones. This can be seen in brain activation too: Chinese people will find looking at excited faces less rewarding compared to European Americans. These variations are likely to extend to depression, Tsai thinks, because it’s another example of a narrow definition of what an emotion is supposed to look like. In other cultures, it might simply not be true.

“Many cultures don’t even have a general concept of emotion,” Tsai told me. “That might be characterized as ‘Oh, they’re not emotional.’ But it doesn’t mean that they don’t have specific emotional experiences. I think Western culture, or psychiatry [and] psychology, privileges people’s ability to articulate their states in terms of mental states and psychological states. But it might not be that describing your emotions in terms of your physical states is any less of a way of doing it.”

Visual: White House photo/Wikimedia

In the end, there was something physically wrong with me. I was eventually diagnosed with a dysautonomia called Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), which means that my body doesn’t do a great job of regulating my blood pressure when I move around. That moment of dizziness you get when you stand up too fast? That’s what I was feeling all the time.

My cure was table salt, 1 gram each day, to raise my blood pressure. It worked, my dizziness went away. But something else went away around the same time: my back-breaking anxiety, and my depression resulting from that anxiety. It wasn’t solved by the salt, but from regularly going to therapy, graduating college, renewing my passion in writing, and finding a partner.

Recently, I stopped taking my salt pill. First I skipped a day, terrified the dizziness would come back. Then I skipped two days, then three. I’ve been completely off them for five weeks and haven’t had any attacks. My cardiologist said this might happen, that I might grow out of it. But even now, I question the diagnosis. What was real — my anxiety, my depression, or POTS?

I’m still stuck in the idea that one must be more “real” that the other. Body or mind — my American culture shining through. But what of the Chinese side? I didn’t feel like I had a choice to feel dizziness instead of a more psychological expression of anxiety. In reality, I know I experienced both. At the same time, whether I have POTS or not, I did spend two years in doctor’s offices seeking help for physical symptoms before it even dawned on me to see a therapist. It’s clear which culture’s help-seeking method I prioritized.

Almost two decades after Kleinman’s seminal study in China, I went to Harvard to see him. If the American emotional life is bleeding its way into China, Kleinman’s office offers refuge. In it, I found an American man submerged in the Chinese. All the books and paintings were of China, its culture and its people. Kleinman himself drops into Chinese effortlessly, with an accent my mother would raise her eyebrows at, and say, “impressive.”

Kleinman still believes that the political turmoil and trauma of his original study influenced the behavior he encountered, and what symptoms people felt safe expressing. But he doesn’t think what he saw in 1980 should be pathologized, or even considered unusual. He now thinks it should be seen as precious.

“In the past and even in the present, many psychologists and psychiatrists saw this as a limitation or even a pathology,” he said. “I completely disagree now. I believe it’s a virtue of Chinese society. We live in a world that’s overly psychologized, and that reflects the hyper-individualism of the West, which has now extended completely to young people in China.”

Kleinman says this with a hint of sorrow. “It’s not in my view, a somatic experience of depression that is different. It’s the psychological experience of depression,” he said. “I think that the world we live in has changed, and with it, the perceptions of feelings and the actual feelings themselves have changed. If your mom treated you in a traditional Chinese manner, for example, she expressed her love, not by telling you, ‘I love you,’ which is an American thing, but by expressing it in the food she gave you, and the things she did for you.”

I had been so focused on depression, and other dark feelings that somatization could be covering, that I was jolted by Kleinman mentioning love.

In a rush of sentiment, I think back to my three-year-old self, taking a nap beside my Chinese grandmother. She would gently scratch my arms until I fell asleep, attending completely and only to my body. Laying in the afternoon warmth, my arms stretched out toward her, like a plant reaching for the sun. My grandmother also made clothes for me (and my body). When I saw her in China last year, I complimented a shirt she was wearing — blue with white flowers. She immediately took it off and insisted that I take it home with me; literally taking the shirt off her back for me.

My mother’s garden was also filled with this type of wordless love. Once the summer months took hold, her guava bush yielded dozens of egg-like fruits. The more oblong and light green guavas — more sour — we would eat first. The holy grail were the guavas that were perfectly round, the kind of perfect circle you’re not supposed to find in nature. They were a deep green, and we knew that the flesh of those guavas would contain the sweetest burst of flavor. After cutting it in half, and reveling in its perfection, she would often let me eat the whole thing.

I’m thinking back to Chentsova-Dutton’s constellation, and the points that make up the story of Chinese depression and distress. The headaches, dizziness, the insomnia — all stars that burn too brightly. I can feel their gaseous fiery nature. They’re painful.

But I have another constellation, too — the one of Chinese love. It’s less about the words “I love you” than it is about round guavas and arm tickles; homemade clothing and my mother eating the stringy center of the mango so I could have the pieces that melt like butter; my grandfather hand-squeezing my orange juice, and my grandmother giving me slippers to wear so my feet don’t get cold.

These symptoms of love involve the body too, but these stars don’t hurt. Like the sun, they have incredible warmth.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this piece stated that the word “soma” is Latin for “body.” The word is Greek.

Shayla Love is a Brooklyn-based science writer. She has a Master’s degree from Columbia University in science, environment, and medicine journalism. Her writing has appeared in STAT, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post, the Kenyon Review, the Atlantic, Harper’s Magazine, Gothamist and BKLYNR.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Just want to say that I definitely learned more while reading this! I am a therapist and trying to continue to be better for all of my clients, including Chinese and Chinese-American clients. Also loved the visual stories of moments with your grandmother <3

Yes, the Chinese have built their emotions into an objective existence. The Chinese do not agree with the individualism of the West. It is only based on a specific natural existence. The Chinese tend to outsmart the spirit from a specific body, so we can also detach from the emotions. That’s why we don’t use “emotional” vocabulary to express, because they are just abstract things as words, we don’t think that “self” can be replaced by these things.

Interesting cultural observations, reflecting ideas of the individual in society in the two cultures. But, I think it overgeneralizes: within cultures in individuals there is surely a great deal of variation? And the loving examples the author gave are not unlike those expressed by American mothers; its not only verbal affirmation; in fact that is not so common as a variety of physical expressions of love, I think.

I have to wonder if, rather than focusing on an Asian inclination to describe physical sensations rather than emotional ones, we should not also consider the affects of unhealthy cultural and religion-based influence in European-Americans which drive us to disconnect from the body in favor of intellectualizing experiences instead.

Thank you for a very insightful piece Shayla.

I found it funny the way you wrote about devouring entire guavas in front of your mother. Surely you could have shared them with her to make sure she didn’t go without?

The act of the mother letting the child eat the entire guava is a very typical Chinese example of showing love. The act of the child eating the entire guava is not only receiving that love but returning the love. In Chinese culture, giving by the elder is to the children is how love is demonstrated. The child must accept and in this case eat the entire guava to show their acceptance of the parents love. There is a Chinese concept not mentioned in this article called “Face” and it’s about maintaining “Face” against all odds. In the case of the guava, the parent wants the child to eat it, because they are showing their love. If the child tries to share it, it is like a partial rejection of the physical fruit offering which is somehow translated into a partial rejection of their offer of love, because that’s how they are communicating their love in the first instance. When that type of “rejection” occurs it’s known as “losing face” when you visit China and are offered something, you must always accept, otherwise it’s considered that you are rejecting their friendship/love/business etc. For example a business deal with a traditional Chinese businessman could fall flat if you reject his offers of a cigarette and alcohol because he feels a sense of “lose of face” or another way to put it , he feels you don’t value him equally in return, and as such is a sense of rejection, so to “save face” he may retreat from the business deal with some general unrelated explanation. Leaving you wondering what went wrong. Chinese culture is highly influenced by the concept of “Face” and it ties into how Chinese people attend to others. Often you can see this in Chinese New year with the exchange of Red Packets known in Chinese as Hóngbāo which are envelopes of cash, and the giving of these. Pride is taken in being able to give the most in a family or friends circle. It’s not about showing off how much your received but rather how much you gave. Often Chinese will give you something unexpectedly as a friend or foreigner to show their appreciation and they will insist they you do not need to pay or return the favor. If you insist it then becomes a form of rejection of their giving. So the eating of the entire guava by the child is the acceptance of the motherly love and showing that they love their mother in return. For the mother to watch the child devour the entire guava is pure joy for the mother. On another level of you think about it, it’s like a mother providing life and nourishment to their child, who is the most important to them. To go without as the mother, and watch is a wholesome and selfless act of giving and they are deriving joy from that act.

From time to time, we found interesting different ways of emotional expression in people. This article helps us to summarise it. Despite our backgrounds, we should live with a combination of mentality and physique. It is important to maintain the body-mind equilibrium.

Excellent article! And especially appreciated that the studies you referenced were easily accessible and accurately hyperlinked – a small but important hallmark of good science writing :)

POTS is a real disorder that can easily cause anxiety. Don’t fall into a trap of thinking that EVERYTHING Is somatasisation (correct spelling in my country btw grammar nazis).

Insightful article. Having experienced both POTS and the implications of the benefit of love, plus Chinese culture I would say this. The article is highly observant in nature. Love increases circulation and in fact, can raise our blood pressure as we may know! When you have POTS, this is from my knowledge due to a lack of response in the integrity of the walls of blood vessels…ie an actual collagen deficiency.

Salt, of course, raises the blood pressure but does not change the state of the strength of the vessels to “pump’ fluid back and forth so to speak. When a person with POTS stands up, from my experience anxiety increases. My own observation is that there is an adrenaline response a few seconds preceding a feeling of faintness. This adrenaline as we all know is for the fight and flight purpose, (not for simply standing up in the shower in the morning)!

POTS is a seriously real condition. It is often associated with those who are very physically flexible in nature for the same reason. None of this is rocket science. It is fascinating that Western medicine is highly aware of the lack of venous integrity but do not recommend a method to increase collagen. Such lack of integrity can also lead to aneurysm.. again lack of integrity of the vessel wall. So those with this condition have to seek a high state of philosophical interest. to keep the circulation ‘up’. Cannot indulge in many things due to this very real physical situation. Personally, I find long-term high dose vitamin C and zinc to have significantly reversed some of this. But has to be taken daily. If you look at cell mitochondria, use Co Q10.. this can be of similar experience to a focused meditation on love. Sitting martial art mind practice can do the same. Heaven help you if you are surrounded by nonlove in your environment. As this resultant improvement in energy cannot be sustained. Again the structure of the walls of the blood vessels is key and organic. People with POTS are often the most daily hard at it people and ironically tremendously strong, even if they do not look so.

Love will increase our circulation. It has occurred to me at times that the body is very clever. If there is such a lack of integrity in the vessels walls and hyper-flexibility if you like. Can you imagine what would happen if the pressure was raised too high, before, the strength of the walls of the vessels were improved? Aneurysm! Clever body. Nothing to do with the mind per se. However. I would like to see those with high blood pressure, without arterial disease, perhaps also sent to seek philosophically and mind assistance. Not just given pills for an easy fix. There is a distinct judgement in the negative to those when pharmacy has not yet produced a drug to assist the issue seek assistance. Sometimes things are hidden in plain sight. POTS being one of them. This article makes one thing clear though. We are perhaps all in control of our own destiny.

Very nice article–understanding and subtle. Very enlightening. Were I still teaching, it would be mandatory reading.

Very interesting article that is very close to my heart. I was born to a Chinese father and a Caucasian mother at a time when that was a very rare occurance. I was raised in Hawaii among my Chinese father’s large extended family so that is the culture I identify with the most. Your article is an insightful discussion of the cultural differences that I observed growing up and sheds some light on my own behaviors!

thank you for such an insightful and uplifting discussion….resonating with many of my observations and clinical experiences