Women, Politics, and the Cultural Biases of Being ‘Presidential’

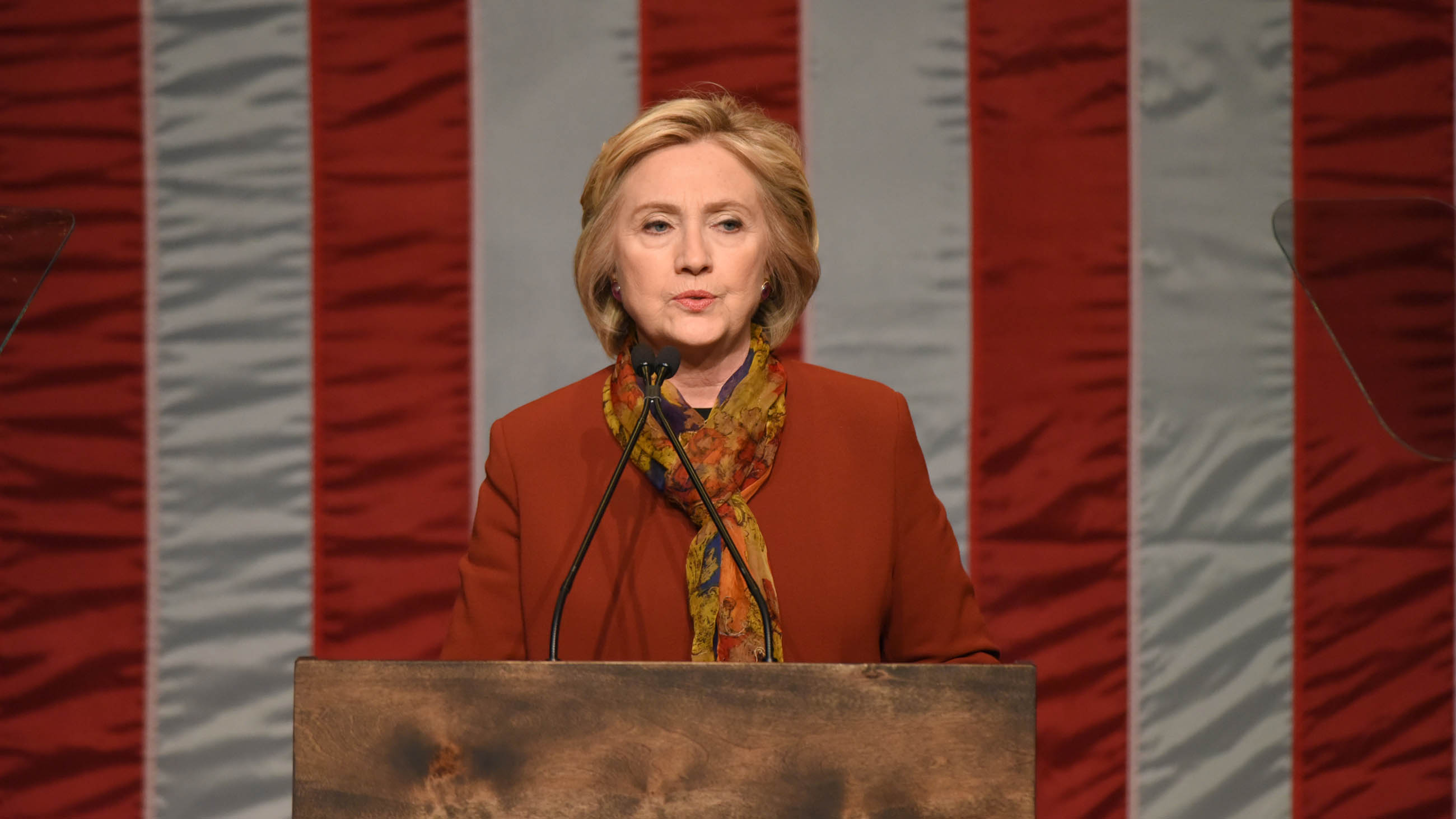

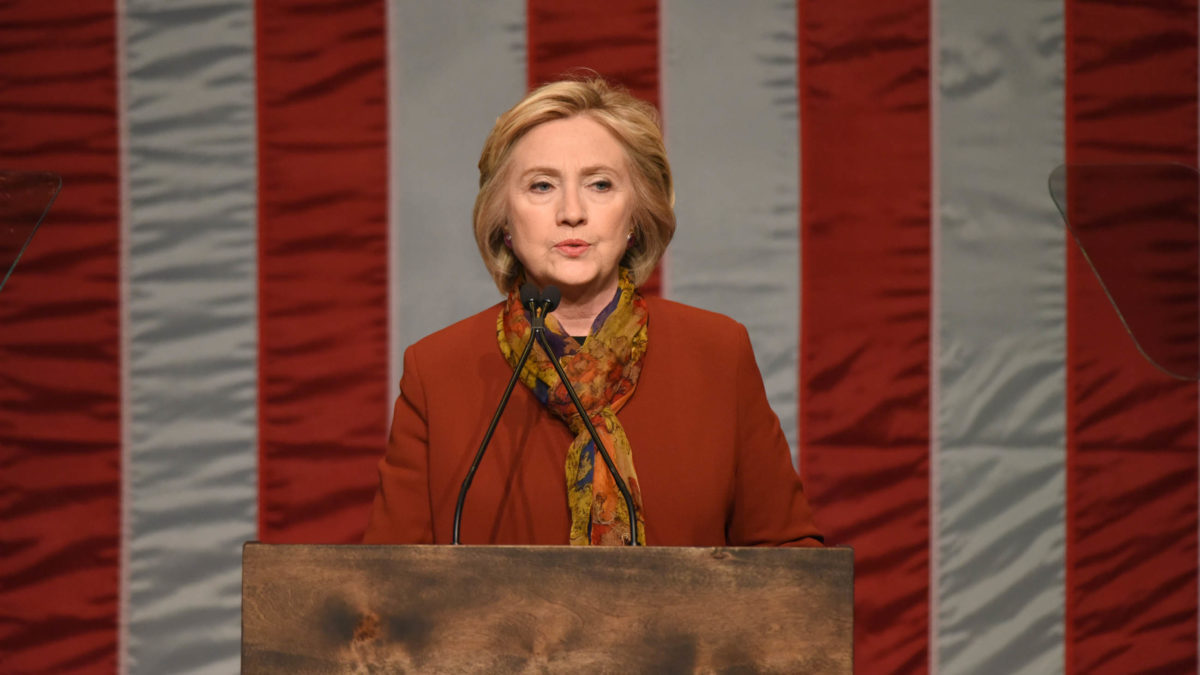

During this week’s presidential debate, Republican hopeful Donald Trump revisited previous attacks on the appearance and fitness of his Democratic rival, former Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton. “She doesn’t have the look,” Trump declared. “She doesn’t have the stamina.”

Later, responding to a lengthy and somewhat disjointed discourse by Trump on the issue of nuclear weapons and U.S. foreign policy, Clinton said: “Words matter.”

If Hillary Clinton succeeds in her bid for the presidency, she will have overcome a lot of cultural baggage among American voters.

Visual: iStock.com

They very much do, research suggests — and so, too, do a host of other factors in the delicate dance that unfolds between presidential candidates and the voters who will determine their fates. For decades, psychologists, sociologists, and political scientists have studied a battery of indicators to assess how the public perceives a candidate’s suitability for the presidency, and how they ascribe traits like empathy, competence, integrity, and the ever-elusive likability to those contenders they ultimately consider “presidential.”

The variables run the gamut, from tone of voice and gestures like pointing or frowning, to overall carriage and posture — and even factors well outside the control of a candidate, like the relationship between facial shape, perceived height, and assessments of leadership ability.

With Hillary Clinton now closer to winning the Oval Office than any woman has ever come, a clear undercurrent of gender bias is now, as it has been in the past, a key part of the perceptual mix — though some researchers see her as uniquely poised to upend some of the most entrenched thinking. “Clinton’s candidacy will definitely affect women’s candidacies in the future,” said Monika McDermott, a professor of political science at Fordham University. “Clinton is very self-possessed, assured, and strong. These are all of the things the voters expect from a president,” McDermott said. “In other words, Clinton is not your stereotypical woman [and] she has been in the public eye long enough to overcome that stereotype. Any future female candidate will need to have the same stereotypical defiance to be a viable presidential candidate.”

Just how far that influence will ultimately reach remains an open question, of course — particularly with the outcome of the election still very much up in the air. And as evidenced by questions surrounding Clinton’s voice, or her ability to be a grandmother as president, and even her fashion sense (“Would you ever ask a man that question?” was her response to one query about her clothes), women — who make up just 20 percent of Congress — still face special hurdles when aspiring to national office in the United States.

“Women are already at a disadvantage as public leaders because many traits expected of political leaders are identified as masculine traits, like being commanding, being decisive, being rational, being strong,” said Valerie Sperling, a professor of political science at Clark University who studies the deep-seated ties between masculinity and political legitimacy. “When women are being commanding, decisive, rational, or strong, they come off as not being feminine enough.”

That leaves women with a very fine line to walk, Sperling said, and it can often mean navigating a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t minefield of public expectations. “You’re wrong basically no matter what you do,” Sperling said. “If you wear the v-neck there’s too much cleavage. If it’s a crew neck it’s too matronly.”

The double standard holds not just for appearance, but tone of voice and other character traits the public uses to deem a candidate “presidential.” Where a shouting Bernie Sanders might be perceived as having strong leadership ability, Sperling suggested, Hillary Clinton’s tone might be described as shrill. “There’s a lot of sexism around that,” she said. “People say ‘she sounds like my mother-in-law’ or ‘she sounds like my first wife.’ But nobody says ‘he sounds like my first husband.’”

For her part, Sperling thinks Clinton’s temperament during this week’s debate was “very poised, confident and pretty unshakeable.” Had she become angry, though, the public would have perceived that as emotional and uncontrolled, Sperling said. Men, on the other hand, are permitted to become angry, especially on the political stage. “Being blustery or angry like Donald Trump — that’s something that’s associated with masculinity,” she said.

Erik Bucy, a professor of communication at Texas Tech University who studies presidential debates and politicians’ nonverbal communication, suggested that Clinton appeared well prepared for Trump’s outbursts of anger and defiance. “Hillary can retaliate with a smile repertoire,” he said. “Some are genuine smiles, but she’ll also have controlled contempt smiles — really kind of a smirk or smile of disapproval — and then she’ll have a composed amusement smile. She used them all [this week] to try and signal to the audience that this is how you respond to his bluster.”

Michael Woodworth, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia, offered a similar observation to Quartz. “[I]f anything, the smiling may have been exaggerated as an attempt to goad Trump into becoming aggressive or flustered,” Woodworth was quoted as saying, “or to make him and his statements appear comical at best.”

That sort of strategy might be more than an effective debating tactic: It might also be helping to dismantle, albeit slowly, the perceptual biases that have kept so many American women out of high office —something that other nations have long ago overcome. Of course, the looming election might prove otherwise. “It’s too early to tell with any finality,” said Barbara Kellerman, a lecturer in public leadership at Harvard’s Kennedy School who recently wrote about the debates. “You can point to any number of women leaders, but the truth is they are very, very few and far between.

“We don’t really have much of a sense of how a woman should look when they’re in power,” she added.

What’s certain is that voters are likely to be at least as attuned — if not more so — to their perceptions of a candidate’s character and comportment with notions of leadership, as they are to their policy prescriptions. “Part of what goes into the decision calculus is the visceral reaction people get from the candidate, not necessarily a policy,” said Vincent Hutchings, a professor of political science at the University of Michigan studying the 2016 election as part of the American National Election Studies (ANES), a project that has been collecting data on voter preferences since 1948.

“The model American voter is much more concerned about [impression] than the GDP,” Hutchings said. “It’s pretty much been like that since we started doing these surveys.”

This post has been updated to add comment from Fordham political scientist Monika McDermott.