Science vs. Stigma: The Continued Criminalization of HIV

Kerry Thomas was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, in 1988. He was 24 years old at the time, living in Boise, Idaho, and figuring out what he wanted to do with his life. Chasing memories of childhood years in Southeast Asia with his Air Force father, he’d decided to enlist. A military physician discovered the illness during Thomas’ medical exam. He was called back for a discussion and left the office rejected by the Air Force and with the understanding that he had less than two years to live.

A year later, Thomas — now struggling with drug and alcohol abuse — had sex with his roommate, Amy Davis. Some weeks later, due to either suspicion about Thomas’ claim that he had leukemia (her story), or anger because Thomas wanted her to leave the apartment (his story), Davis rummaged through his belongings and found the military document with his HIV test results. In April of 1990, she went to the police and detailed how Thomas had attempted to expose her to HIV — a new crime established under a law approved by the Idaho state legislature just two years earlier.

Hear more from this story’s author, Jessica Wapner — along with segments on sexual harassment in science, and research into near death experiences — in our latest Undark Podcast.

The ensuing investigation turned up eleven additional victims. Although the exact details vary somewhat, all the reports note that Thomas ejaculated inside the women without using a condom and without disclosing his disease status. The charges, spanning from April 19 to May 5, 1990, included statutory rape, because one of the women he’d slept with was under age 18. In a deal struck with attorneys, Thomas pleaded guilty to that charge, and the HIV-related charges were dropped.

He was sentenced to up to 15 years in prison, but was released after 19 months.

In 1996, Thomas — now married — was arrested again for having sex without disclosing his HIV status. The victim was Camille Garver, who, according to legal documents, described herself as a preoperative transsexual. After meeting at a club in downtown Boise, the two spent the night at Garver’s apartment and engaged in anal and oral sex. This time, Thomas refused to plead guilty and the case went to trial. The jury believed the victim and Thomas was sentenced to 15 years.

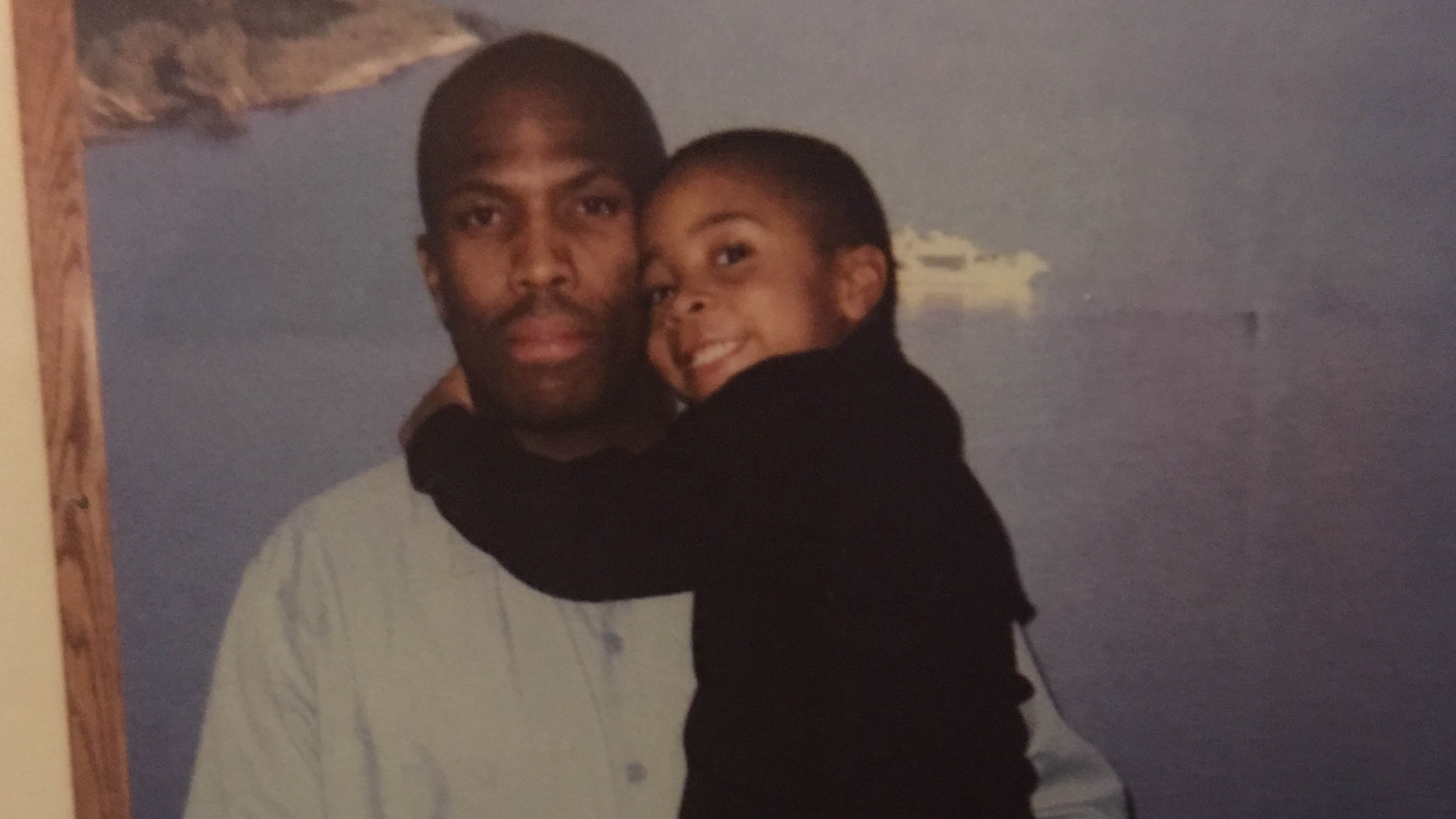

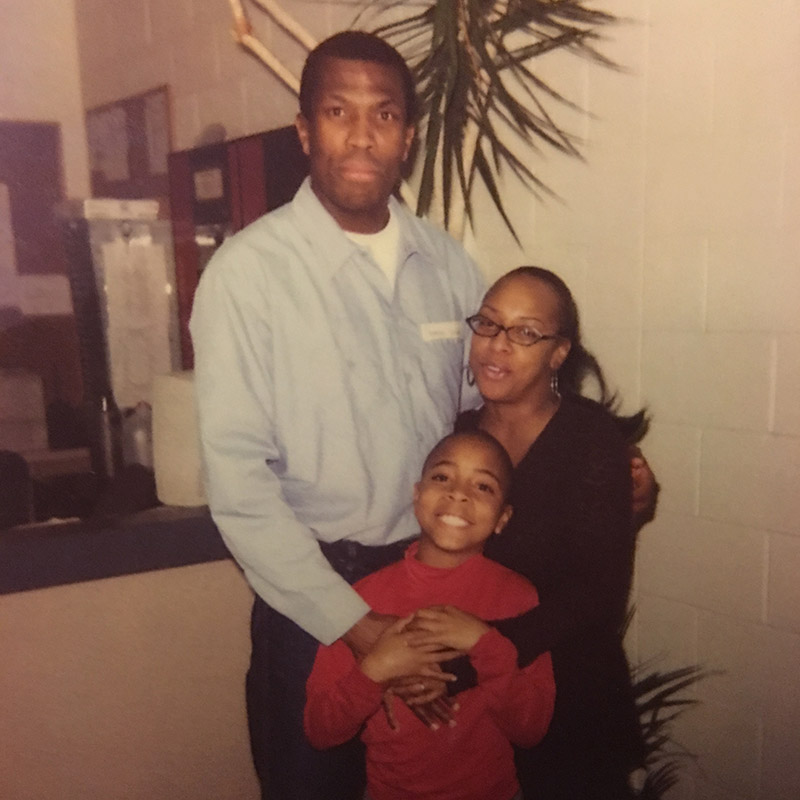

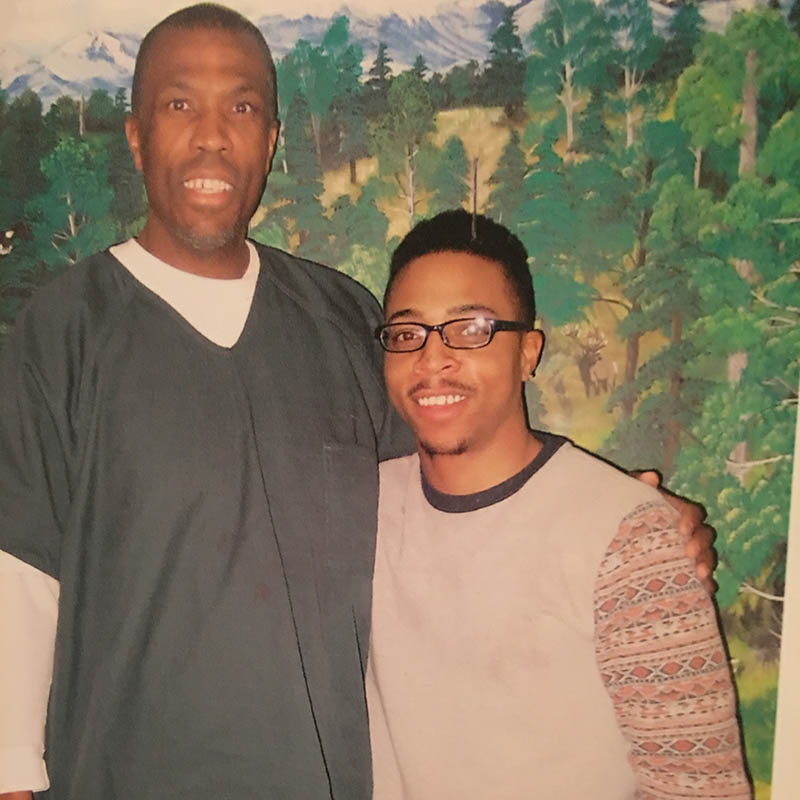

The trial took a toll on his wife, Felicia Wells, and the couple’s two-year-old son, Nygil. “They ended up putting my address in the newspaper,” said Wells, who knew of Thomas’ HIV status when they married. She separated from Thomas and moved to Portland with Nygil, whose earliest memories of his father take place in the prison’s visitation room. He still has some photographs from those visits. “We both look lost,” said Nygil, now 22. “Just real sad.”

Thomas was paroled in 2003. Five years later, he began dating Diana Anderson, a former co-worker at the real estate firm in Boise where he worked as an administrator. In the early weeks of their relationship, Anderson invited Thomas and a couple of friends to a yoga class. One of the friends thought he recognized Thomas, and soon remembered who he was: the sexual predator who spreads HIV.

On December 31, 2008, Anderson went to the police. Thomas, who had been in Portland visiting his son, was arrested at the Boise airport upon his return for violating his parole. A few weeks later, he was charged with attempting to transfer HIV.

This time, on the advice of his lawyer, Thomas pleaded guilty to two counts of HIV nondisclosure. The prosecutor, Jean Fisher, requested the maximum 15 years for each of the two counts. The judge agreed. “You have shown that you cannot be trusted in this community to not create other victims,” he told Thomas. He sentenced Thomas to a total of 30 years, with parole considered only after at least 20 years were served.

Nygil was in the courtroom that day. “I get why he took the plea, otherwise he might have been there his whole life,” he told me. “But he got his whole life anyway.”

Now 52 years old, Thomas will be in prison at least until the year 2029 and possibly until 2039.

Today, Thomas admits to only three instances of having sexual contact without disclosing his HIV status, all within the two years following his initial diagnosis in 1988. He also accepts the statutory rape charge. But he disputes all of the other HIV-related charges and accusations leveled against him over the decades, and after several phone interviews with Thomas, a seven-hour visit with him in prison, and having read piles of related court documents, news stories and police reports, I still can’t pin down the truth.

One fact, though, remains undeniable: Kerry Thomas has never infected a single person with HIV. Whatever one thinks of this man — whatever judgments we attach to the way he’s lived his life and the decisions he’s made along the way — that fact matters. It may be the only one that does.

At least 30 states currently have statutes on the books that specifically forbid people infected with HIV from potentially exposing others to the virus. Several more states prosecute under broader communicable disease laws — and all of these laws persist despite what is now decades of scientific knowledge putting the virulence of HIV well below a menagerie of other common pathogens. Hepatitis B, for example, is another sexually transmitted virus with potentially life-threatening consequences, and while some states do include hepatitis B in their non-disclosure statutes, failure to admit an infection to a sexual partner is rarely, if ever, prosecuted.

Similarly, a person who knowingly boards a subway while sick with the flu can very easily infect — even inadvertently kill — an elderly person with a weakened immune system, all with a single cough. But a sniffling commuter would never be arrested, let alone charged with a felony.

In contrast, those convicted of HIV-related offenses can, like Thomas, face decades of life behind bars. Some states require people convicted for HIV-related crimes to register as sex offenders — a punishment sometimes worse than prison time.

An exact count of arrests and convictions under these laws is impossible to make because the data aren’t available and many defendants plead guilty to lesser charges. Some states, such as New York, prosecute HIV nondisclosure with regular felony laws. The Center for HIV Law & Policy, a legal aid service, counted 226 arrests or prosecutions between 2008 and 2015. A 2010 report on HIV criminalization by the Global Network of People Living With HIV estimated the total number of prosecutions at more than 400 and total number of convictions at more than 300. According to the United Nations, many of these rulings carried sentences of 25 years or longer. A recent ProPublica investigation found more than 500 convictions between 2003 and 2013.

Whatever the real number, AIDS activists — and most researchers familiar with the disease — say it is too high, and they insist that the laws are an affront not just to human rights, but to science itself. Some signs of reform have begun to emerge, but the stigma of HIV — born out of a lingering mix of early-epidemic hysteria and banal racism, classism, and homophobia — is a high hurdle.

“Any law that criminalizes behavior based on the medical condition of HIV,” wrote Eve Hill, Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, in a statement provided for this story, “should reflect the modern science of actual risk of transmission.”

To date, most laws do not.

Kerry Thomas appears in a video produced by the Sero Project, which seeks to end criminalization of HIV.

Even in the absence of condoms and medication — and despite a well-cultivated cultural perception to the contrary — HIV has never been that easy to transmit. Receptive anal intercourse with an HIV-positive partner carries a 1.38 percent chance of transmitting the virus. In other words, on average, it takes 72 such exposures to get infected. For an uninfected woman having vaginal sex with an infected but asymptomatic man, the risk is 0.08 percent, or 1 in 1,250 exposures. An uninfected man having sex with an infected woman runs a 1 in 2,500 chance of contracting HIV. Oral sex poses a very low risk to an HIV-negative giver or receiver.

In this light, even by the most conservative measure, the risk of HIV transmission is far lower than popularly understood. And when protection and modern medications are deployed, that risk is as close to zero as possible without actually being zero.

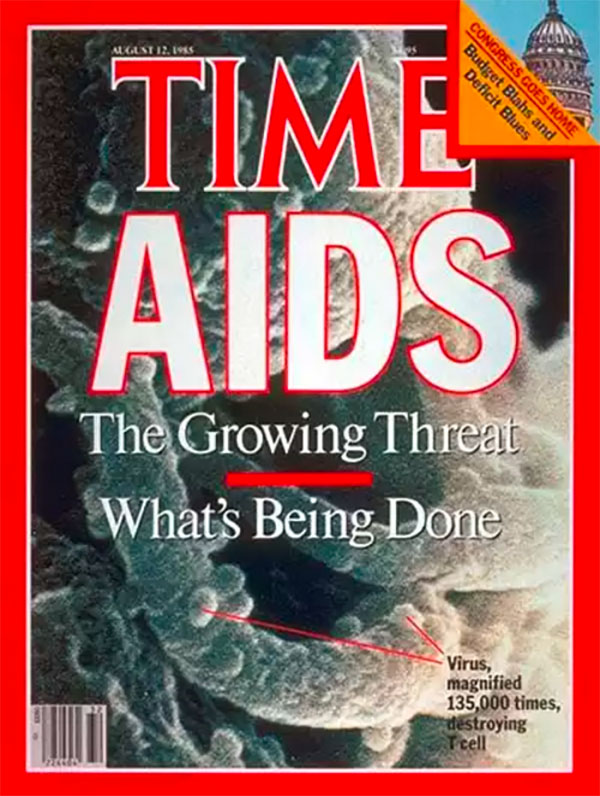

Of course, such sober assessments of the risks associated with HIV transmission were hard to come by 30 years ago, when AIDS had all the hallmarks of a looming epidemic, albeit one that was largely confined to a few sub-populations — promiscuous gay men, intravenous drug users — with a high prevalence of the infection. Casual contact — shaking hands or the use of public toilets — were feared as potential routes of transmission, and the lag time between infection and the appearance of symptoms meant that people who did not know they were positive continued spreading the disease. Preventive measures were not uniformly embraced, and the disease was untreatable.

Jay Dobkin, an infectious disease specialist who directs the AIDS Program at Columbia University Medical Center, recalls a succession of stump-the-expert cases presented at multi-hospital infectious disease rounds, as growing numbers of men showed up with “a bizarre pneumonia.”

“Beginning in the fall of 1980, every week somebody had a case,” said Dobkin.

Out of nowhere, previously healthy, young, gay men — mainly in New York and California — were contracting unheard of problems for their demographic. They often presented with Pneumocystis carinii, an infection usually confined to people with a previously diagnosed immunity-suppressing condition. Sometimes they showed signs of thrush, a fungus that grows in the mouth as white spots, and Kaposi’s sarcoma, cancerous skin lesions caused by viral infection.

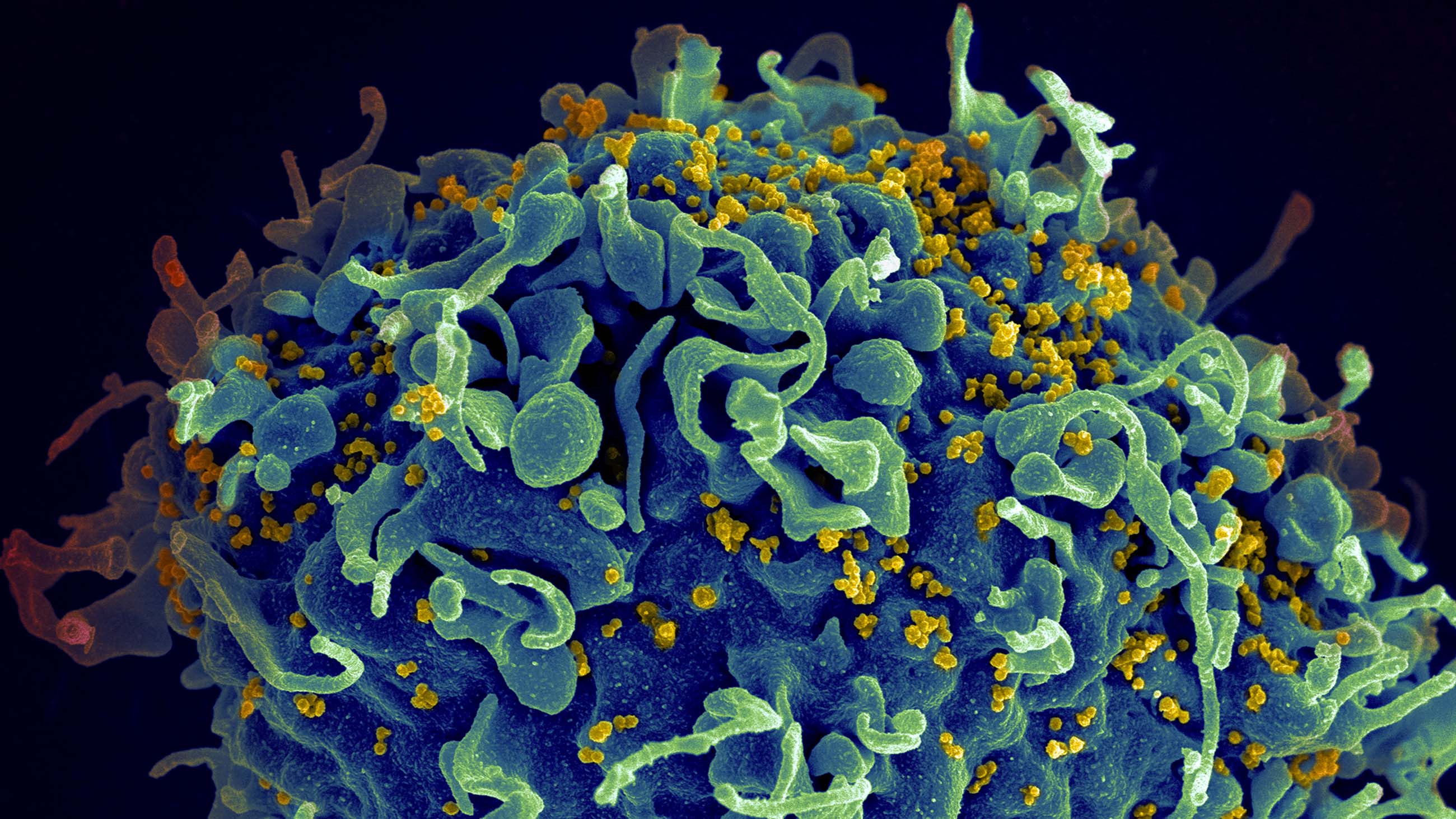

By 1982, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had named the underlying condition: acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS. Evidence that the disease was sexually transmitted abounded, though cases among infants, injection drug users, and recipients of blood transfusions were also documented. In 1983, Luc Montagnier, a scientist at the Pasteur Institute, found the virus in the blood of people diagnosed with AIDS. A year later, Robert Gallo, of the National Cancer Institute, provided evidence confirming that the HIV virus caused AIDS. A diagnostic test for HIV, which detects antibodies to the virus, became available in 1985, and Montagnier and Gallo opened the door to what is now a vast understanding about why HIV was so insidious.

In this video, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute explains the mechanism of HIV infection.

The pathogen’s genome is comprised of RNA rather than DNA — the same as measles and polio, and even the virus that causes the common cold. Most RNA viruses work by releasing their RNA into the cytoplasm of a cell, where new virus is continually manufactured until the cell essentially explodes. This leads to the infection of more cells that, in turn, also succumb to the virus.

Typically, the body mounts an immune response to this sort of uncontrolled virus proliferation — sometimes with the assistance of a vaccine or medication — and the infection is eventually eliminated. RNA viruses aren’t necessarily harmless, but they can be overcome.

But HIV is a special kind of RNA virus known as a retrovirus. Measuring about one-tenth of a micron (that’s one-tenth of a millionth of a meter) across, HIV consists of two RNA strands inside a protein coat, within an envelope membrane. It targets the body’s T helper cells — white blood cells that regulate immune responses — with ruthless efficiency. A glycoprotein on HIV’s membrane first seeks out and attaches to CD4, a corresponding glycoprotein on the surface of a T helper cell; the virus then latches onto another protein, called CCR5, which acts as doorway into the cell.

Once the virus is inside the cell’s cytoplasm, the real havoc begins: An enzyme called reverse transcriptase is used to generate complementary DNA that is then ushered into the cell’s nucleus, where our genetic code is stored. This complementary DNA is stitched directly into the genome of the host, meaning it becomes part of the very fabric of the infected person.

“It’s as though it were designed to do bad things,” said Sarah Schlesinger, an associate professor of clinical investigation at Rockefeller University, of the HIV virus.

Destructive as the virus is, the body has myriad defenses, and exposure is by no means a guarantee of infection. While the mucosal surfaces of the body, for example — wet areas like the inside of the vagina and anus — have fewer layers of protection than the skin, the virus still must make its way through tightly knit matrices of epithelial cells in order to penetrate the body and spread.

The human immune system also recognizes HIV as a foreign invader, and its cellular defenses are capable of killing virally infected cells. But the virus can go latent in our cells, and it can mutate to escape the immune defenses. Over the years that follow infection, T helper cells become depleted, leaving the body vulnerable to all sorts of opportunistic pathogens and infections. This is the immune-deficient condition known as AIDS.

And yet, for all of this, medical advancements have been comparatively swift. By 1993, AIDS was the leading cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44. But the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, or HAART, in 1995, ended the certain fatality of infection. By interfering with processes required for viral replication, HAART reduces the amount of pathogen circulating in the body — the viral load, in medical terms — to undetectable levels. This means the virus is unlikely to be found in semen or vaginal fluid.

“If you can’t detect it in the blood,” said Schlesinger, “it’s not going to be anywhere else either.”

The practical implications of this innovation are hard to overstate. Although people infected with HIV are not yet living the same lifespan as their uninfected equivalents, they are coming remarkably close. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and a leading researcher of HIV, notes that in the early 1980s, fifty percent of people who became infected would be dead within 18 months. Today, a 25-year-old infected with the HIV virus and subsequently put on triple combination therapy can expect to live, on average, another 50 years — “just a few years short of the normal life expectancy,” said Fauci.

The medication is available as a single daily pill and causes few and usually mild side effects.

Proper treatment is estimated to reduce the HIV transmission risk by 96 percent. Adding a condom brings that reduction to 99.2 percent. In other words, if someone infected with HIV wears a condom and takes the right medication, the odds of transmitting the disease during sex are extremely low.

The global view of HIV is also improving, albeit at a slower rate.

From the start of the epidemic, prevalence and death rates in the developing world, particularly in Africa, far outpaced those in the U.S. By the end of 1997, nearly 10 million adults and children had died of the disease in sub-Saharan Africa. And whereas the U.S. death toll began declining after the advent of HAART, no such parallel was seen in that region because the medications were unaffordable and the drug makers refused to allow generic versions of antiretroviral drugs to be sold there.

Today, the developing world carries most of the global HIV burden. Of the estimated 36.7 million people living with HIV worldwide, more than half are in eastern and southern Africa, with another 18 percent in western and central Africa. For a variety of troubling reasons, women in sub-Saharan nations are particularly hard hit, representing more than half of new HIV cases. A quarter of all new infections in adults are in women between the ages of 15 and 24. In the United States, women of any age account for just 19 percent of new HIV diagnoses.

Still, the hard-won availability of dollar-a-day treatment in 2001 and other prevention and treatment efforts have slowed the rates of HIV infections and AIDS deaths in the developing world. Since 2010, the number of eastern and central Africans living with HIV who are taking medication has more than doubled, and AIDS-related deaths declined by 36 percent in the region.

Seventeen million people living with HIV are now taking antiretroviral drugs, according to a UNAIDS report released in May. Such access has resulted in a 43 percent decline in AIDS-related deaths worldwide since 2003.

Treatment, of course, is not curative. No matter how low the viral load gets, HAART can never eliminate the infection because some of the virus exists in a latent form. That is, anyone infected with HIV carries with them some virus that, while not actively replicating, remains dormant inside the T cells. HAART can’t target particles that aren’t replicating, and some T helper cells are long lived. To make matters worse, these latently infected cells may be cloned, so even their death does not end the disease.

Latent HIV is one reason why the infection risk is not zero. Another reason is the “blip.” Someone with years of viral suppression can occasionally have a sudden increase in viral load. Skipping medication for a day can lead to such a blip, as can the presence of another infection, like a cold, or a flu shot. Blips disappear and don’t cause long-term damage, but they can be unpredictable.

Undiagnosed disease also poses an obvious infection risk. Soon after the virus colonizes a new host, it replicates in skyrocketing amounts. The first weeks following an infection are the most dangerous in terms of transmission because the viral load is exceptionally high, and however advanced the antiretroviral regimen, unprotected sex with someone who is HIV positive does carry some risk.

“The standard recommendation that I still give to all my patients is use barrier protection,” said Dobkin.

Fauci also cautions that the threat of HIV infection from any given sexual encounter depends on several factors, such as the presence of another sexually transmitted disease, like genital ulcers. Having multiple sex partners matters, too. “Sometimes it’s one in a thousand sexual acts,” Fauci said. “Sometimes it’s one in a hundred.

“Sometimes,” he added, “you’re unlucky.”

This is precisely why discussing and disclosing any potentially transmissible illnesses with intimate partners is encouraged by public health officials. And yet, while laws and public health measures have been enacted around some other communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis, no other disease has been as aggressively criminalized as HIV — even though the virus today is a manageable disease that, when treatment and prevention are used, is exceedingly difficult to transmit.

Kerry Thomas has been in the legal system for half his life, and as of now, he will be incarcerated until he is at least 65 years old. He was locked up when his mother died, and he remained behind bars when he became a grandfather in September 2015.

On the day I visited him in prison in May of last year — and over several phone calls — Thomas was friendly and warm, but also reserved. He mixed earnest reflections with wistful humor as he recounted his version of the circumstances surrounding his various arrests, and his feelings on HIV criminalization laws in general. “The way that these statutes are prosecuted is, in a sense, saying that people who have HIV can’t live a normal life,” he said.

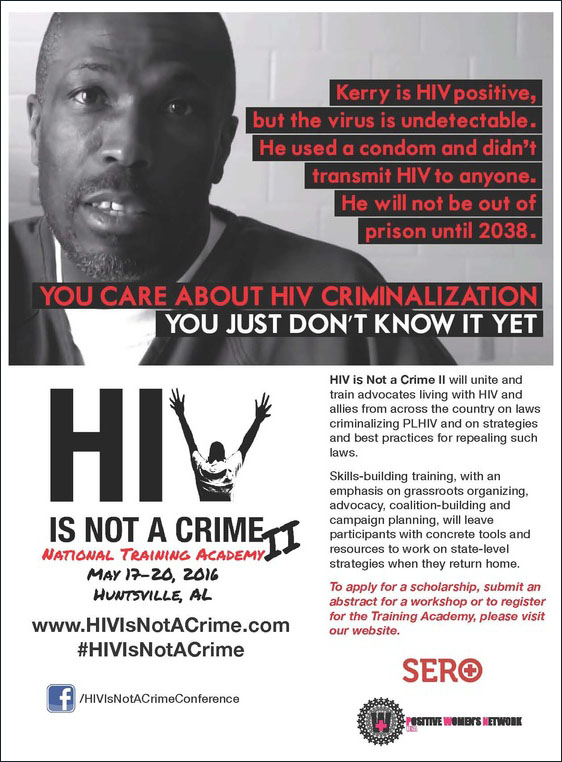

Kerry Thomas has become a touchstone for the HIV de-criminalization movement in the U.S. and abroad.

Visual: hivisnotacrime.com

Thomas now serves on the board of the Sero Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates against HIV criminalization laws, and he has delivered telephone addresses from his confinement in Idaho to conferences in the U.S. and abroad. He says he is in good health and that he sees a physician just once a year.

As Thomas likes to say, the only side effect he’s ever experienced from his disease is the legal system.

“The stigma surrounding [HIV] has been my biggest burden,” he said.

That stigma, along with the criminalization of HIV transmission that it engendered, rose directly out of the earliest days of the AIDS epidemic, which were drenched in hysteria. Even though casual contact was ruled out as a threat by 1983, little could be done to quell the fear of catching AIDS from everyday encounters. When parents panicked and forced the closing of a New York City public school after a single second-grader — in another, undisclosed school — was diagnosed with the disease, a 1985 headline in TIME magazine referred to AIDS patients as “The New Untouchables.”

That same year, a Los Angeles Times poll found that of 2,308 people surveyed, more than half favored quarantining anyone who tested positive for HIV. About 15 percent of respondents thought infected people should be tattooed to warn future sex partners or needle sharers.

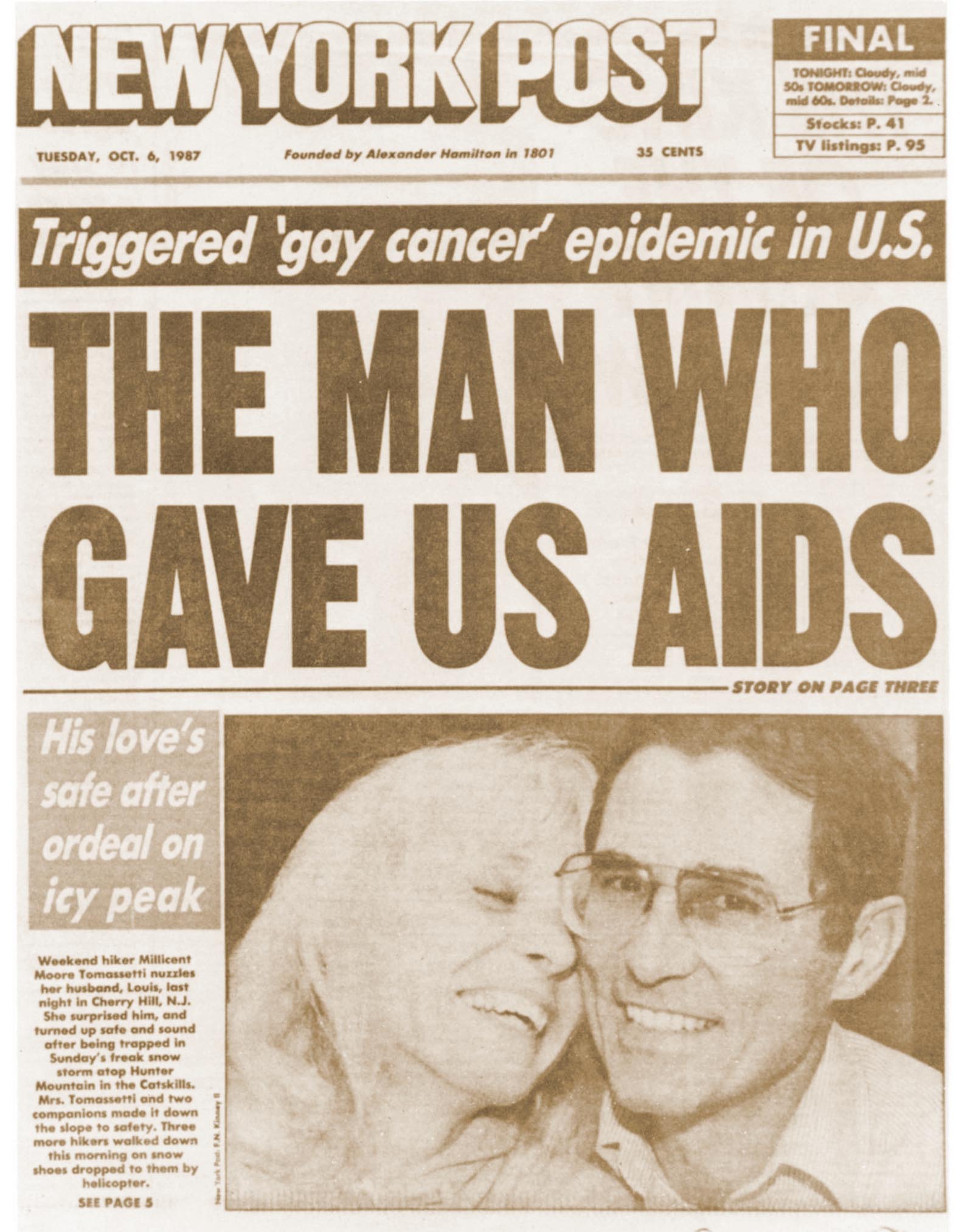

Although the concept of the “AIDS predator” was already looming in the American imagination, the introduction of Gaetan Dugas gave credence and shape to that fear. Dugas was an HIV-positive flight attendant from Quebec who’d had sex with 40 of the first 248 AIDS patients in the United States. The CDC had identified Dugas during its early contact-tracing, which led the agency to conclude the disease was sexually transmitted. But it was the journalist Randy Shilts’ book “And the Band Played On,” which chronicled the early years of the epidemic, that brought Dugas to national attention.

On the verge of the book’s 1987 release, Shilts’ editor, Michael Denneny, decided to pitch the book to The New York Post by spinning the story around Dugas — a handsome, lustful, gay foreigner infecting America with his virus. “Since I believed AIDS was a huge problem and was going to get even bigger,” said Denneny, who was part of the early-1980s gay community in New York City, “I was desperate to find a way to make the media pay attention to the book.”

The tactic worked. “The Appalling Saga of Patient Zero,” a TIME magazine headline declared. The New York Post described Dugas as “The Man Who Gave Us AIDS.” Dugas was the focus of a “60 Minutes” segment titled simply: “Patient Zero.”

Dugas was not patient zero, and the CDC did not label him that way. Rather, as the agency worked to trace the route of the virus, he was dubbed “Patient O,” indicating he’d come from “Outside” of California. As reported by Richard McKay, who researches the history of medicine at the University of Cambridge, Dugas was promiscuous after his diagnosis, but he eventually listened to friends persuading him to change his ways. None of that made headlines, but the caricature of Dugas as a reckless, hedonistic spreader of a disease — one that made the heterosexual suburbs of middle America shudder — had already begun fueling the advent of HIV criminalization.

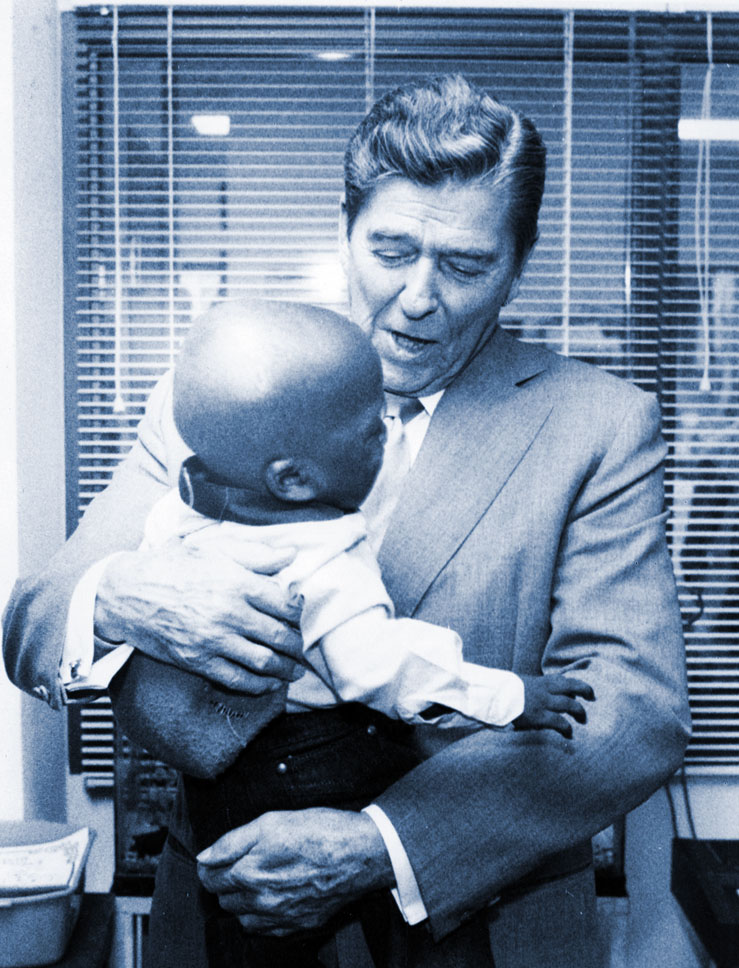

Even outside of the homosexual population, though, AIDS was still largely concentrated in the United States among the other three other H’s: hemophiliacs, Haitians, and heroin users. Those demographics notwithstanding, the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, empaneled by President Reagan a year earlier, recommended that states adopt “a criminal statute — directed to those HIV-infected individuals who know of their status and engage in behaviors which they know are, according to scientific research, likely to result in transmission of HIV — clearly setting forth those specific behaviors subject to criminal sanctions.”

Then president Ronald Reagan holds a child infected with HIV in 1987.

Visual: National Institutes of Health

When the American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative lobby group, published an article calling for HIV criminalization laws in 1989, three years after the first laws were passed, Dugas was cited as evidence for the need. ALEC also circulated its model bill, known as the HIV Assault Act, to state representatives. Several states then converted the ALEC model into legislation.

Despite well-established scientific knowledge about how the virus is actually spread, fears escalated about infection through non-sexual routes — saliva, sweat, tears, urine, bowel movements, kissing and mosquito bites.

So rampant was the panic that Surgeon General C. Everett Koop mailed a letter to every home in America clarifying the routes of contagion. In 1991, Philadelphia police rioted at a rally by the AIDS activist group ACT UP, because they feared the fake ashes carried in a homemade coffin were contaminated with the virus. As a young public defender in that city, Lawrence Krasner recalls courtroom guards throwing away pens used by male prostitutes to sign documents, and sometimes even the folding chairs they’d sat in.

“This terror was there,” said Krasner, “and everybody was in love with locking everybody up.”

By 1990, twenty states had enacted HIV criminalization laws. That year, a federal law known as the Ryan White CARE Act made funding available to help people living with HIV. The bill included a clause requiring states to demonstrate legal means to prosecute cases of intentional HIV transmission in order to obtain the money (this clause was repealed in 2000). Some states declared their existing felony laws sufficient, but others swiftly passed HIV-specific legislation.

The laws read similarly to Idaho’s statute 39-608:

Any person who exposes another in any manner with the intent to infect or, knowing that he or she is or has been afflicted with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), AIDS related complexes (ARC), or other manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, transfers or attempts to transfer any of his or her body fluid, body tissue or organs to another person is guilty of a felony and shall be punished by imprisonment in the state prison for a period not to exceed fifteen (15) years, by fine not in excess of five thousand dollars ($5,000), or by both such imprisonment and fine.

Concern about intentional exposures was legitimate among the hardest hit populations in the early 1980s, primarily homosexual men in California and New York. Denneny remembers ex-boyfriends calling him up, shaken by a new lover’s disclosure of his infection the morning after sex. “It was not mass delusion and hysteria,” said Denneny. “There were people who were doing this.”

To be sure, incidents of at least neglectful, and possibly criminal, HIV exposure and transmission are easy to find. In the late 1980s, a Florida dentist allegedly transmitted HIV to several patients, though no one knew how. In 1998, Nushawn Williams was sentenced to 12 years in New York for allegedly infecting 13 women with HIV, one of whom was 13 years old and two of whom gave birth to HIV-positive babies. In 2004, Anthony Whitfield, of Washington, was sentenced to 178 years in prison for allegedly exposing 17 women to the virus, five of who tested positive.

But cases clearly warranting criminal punishment are rare — and even these individuals, some argue, would be best served by social services, not imprisonment. As with Kerry Thomas, most prosecutions revolve around conflicting stories, behavior that actually posed little risk, and no HIV transmission. Concrete evidence in such cases is uncommon, because disclosure usually takes place as part of an unrecorded conversation.

Of course, passage of HIV criminalization laws began in earnest in 1986, with most hitting the books before effective treatment became available a decade later. But 10 such laws have been passed since the year 2000. Alaska passed its first HIV nondisclosure law in 2006. Nebraska’s came in 2011. A few states have amended their laws in recent years, but most remain on the books as they were enacted.

Federally, the only law criminalizing HIV pertains to the donation of potentially infectious bodily materials, such as blood, tissue, and semen, but according to the Center for HIV Law & Policy, no one has ever been convicted under this law. There are a few federal criminal cases where sentences were increased because the defendant had HIV. Members of the U.S. Armed Forces have received military prison sentences for HIV nondisclosure prosecuted through aggravated assault laws, sometimes even when no sexual penetration occurred. The National Defense Authorization Act for 2014 called for a review of U.S. military policies surrounding HIV nondisclosure.

Just four states — California, Minnesota, North Carolina and North Dakota — explicitly allow condom use as a defense, even though such protection indicates a lack of criminal intent, and condoms are the single best way (besides abstinence) to prevent transmission. In five other states — Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania — condom use is an implied defense. After significant advocacy efforts in Iowa, the governor there repealed the HIV-specific statute in 2014, enacting a more general infectious-disease law that allows “practical means to prevent transmission”— medication and condoms — as a defense.

Where the laws remain tough, maximum sentences can range from up to 10 years to more than 20 years. In several states, HIV nondisclosure is punishable with a longer sentence than that for vehicular manslaughter. And none of the laws currently on the books in the United States require actual transmission of HIV for a charge or conviction to be made.

Back in 1989, no one was likely surprised when a Texas court sentenced Curtis Weeks to life in prison for attempted murder because he spit on a prison guard — a decision that was later upheld. But this is not ancient history. The Center for HIV Law & Policy and the Positive Justice Project have documented hundreds of arrests for HIV transmission offenses over the last eight years — many of them for acts as simple as spitting, even though no case of HIV transmission via saliva has ever been documented anywhere in the world.

The punitiveness is not confined to the United States.

According to HIV Justice Network, an international advocacy organization, 72 countries have criminal laws pertaining to HIV specifically, or that include HIV among other infectious diseases. A 2012 report by the multinational Global Commission on HIV and the Law found that at least 600 people in 24 countries had been convicted under these laws. Whether or not the disease was transmitted is often immaterial, and condom use is only sometimes considered as mitigating evidence. “They push people away from treatment and from behavior interventions,” said Edwin Cameron, a judge with the Constitutional Court of South Africa, of HIV criminalization laws in Africa. “They are monstrous laws.”

One province in Australia has a law criminalizing HIV nondisclosure, as do least nine European countries, 11 in Central and South America, and thirteen across Asia and the Pacific. The Global Commission on HIV and the Law found that these pieces of legislation disproportionately affected immigrant populations.

In January of this year, 30 HIV-positive gay men who were diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection in 2015 came under investigation for violating a Czech Republic law that forbids sex without a condom by anyone living with HIV.

“Science has always been very loosely coupled to the passage of laws, especially criminal laws,” said Zita Lazzarini, a lawyer and public health researcher who has studied HIV laws for decades. “I doubt a single legislature called for a public health analysis on the impact of trying to punish individuals for knowing exposure before they cast the laws.”

Indeed, concern about the archaic nature of these laws is twofold. The first involves the defendants. Individuals who posed no real threat are losing years of their lives to excessive prison sentences, and when viewed against current science and medicine, continued use of these laws is akin to forced lobotomies, or giving pregnant women thalidomide. We now know better — or at least we should.

The second is a public health matter. Ending the HIV epidemic is well within reach. “If there was the global political, economic and sociological will to do it, you could dramatically turn around the epidemic,” said Fauci.

And yet, HIV criminalization laws may be an obstruction. Lazzarini and her colleagues, for example, pointed out in a 2013 commentary in the American Journal of Public Health that incarcerating people with HIV is unlikely to reduce the incidence because the vast majority of people living with the disease are not imprisoned and the disease can be transmitted inside prisons. The research is also inconclusive on whether these sorts of laws actually promote disclosure. Some studies have found that they do, and others have found they don’t.

But by definition, the laws have no demonstrable effect on thwarting transmission from someone who doesn’t know their status — and here is where the laws might prove most counterproductive. The best way to avoid being arrested for HIV nondisclosure, after all, is to be legitimately ignorant about your own viral status.

“There’s this catch phrase, ‘Get tested, get arrested’ that people on the street seem to know,” said Pat Steadman, a Democratic state senator from Colorado who has spearheaded efforts to reform punitive HIV laws there. In addition, some people may fear retribution from partners — a particular concern among women, who are at greater risk of partner abuse than men. Parents may lose custody of children upon an HIV conviction and have few job prospects after release. All of this would make not getting tested seem a safer, and perhaps even more rational, choice for many people.

About 13 percent of the 1.2 million people living with HIV in the United States are unaware of their infection, according to the CDC. Fauci said the undiagnosed are responsible for about 30 percent of new HIV cases.

With these and other factors in mind, several federal authorities have begun calling for modernization of HIV laws, including the U.S. Department of Justice, the CDC, and the Presidential Advisory Council on AIDS. Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential nominee, even delivered a videotaped address to the second annual “HIV Is Not Crime” conference, which was held in Alabama in May. “As president, I’ll work to reform outdated and stigmatizing federal HIV criminalization laws, and call on the states to do the same,” Clinton said. “And I will aggressively enforce our current civil rights laws to fight HIV-related discrimination, stigma, and injustice.”

In a videotaped message, Hillary Clinton vows to reform HIV criminalization laws.

Last year, U.S. Representative Barbara Lee, a California Democrat, introduced the H.R.1586, also known as the Repeal HIV Discrimination Act. Similar bills have failed to make it through Congress in recent years, and no further action has yet been taken on Lee’s bill.

California amended its own HIV law many years ago to require proven intent, bringing it in line with standard felony laws. Illinois has also improved its law. Two weeks after Iowa revised its own HIV criminalization law, the state’s supreme court vacated the conviction and sentencing of 42-year-old Nick Rhoades, who had been arrested for having a one-night stand during which he used a condom and had an entirely undetectable viral load. Rhoades, who was serving a reduced sentence of probation, had his charge dismissed and was removed from the sexual offender registry.

Earlier this year, Colorado passed a bill — sponsored by Steadman — that repealed and reformed some HIV criminalization statutes in that state.

But Kerry Thomas’ fate, like that of many others, appears fixed.

In 2013, the Idaho Medical Association passed a resolution seeking an update of the Idaho statute. Knowing that any legislator considering such a change would consult with state prosecutors, the medical association met with the Idaho Prosecuting Attorneys Association as a first step. If the attorneys objected, then legislators were unlikely to take up the cause.

The IMA talked with several representative prosecutors, including Jean Fisher, the prosecutor on Thomas’ 1996 and 2009 cases. Susie Pouliot, CEO of the Idaho Medical Association, recalled Fisher acknowledging that some aspects of the current law were outdated, but the agreement ended there. Fisher was “very resistant” to an update, said Pouliot. In light of the response by the prosecutors, the medical association decided not to pursue its reform initiative for the time being.

Several weeks before I learned about this meeting, I had asked Fisher whether she saw a need for any change in the law. “That is definitely a legislative decision and that’s got to be done by people within public health and in the public health arena,” she responded. “I’m here to uphold the law. I don’t make it.”

She did not mention the IMA meeting, which took place a year or so before we spoke, and she stood by her decision to request the maximum punishment for Thomas. “I think Kerry Thomas’ sentence is very just,” she said.

“I can only breathe the current breath,” Thomas tells himself. “I can’t do 30 years, but I can do this day.” (Photo courtesy Nygil Thomas)

Not everyone agrees, and advocacy efforts on his behalf — or aimed more generally at upending what are viewed as unfairly punishing HIV disclosure laws everywhere — are escalating. Nonprofit groups were directly influential in Iowa and Colorado, and some 300 people gathered for the Alabama conference where Hillary Clinton delivered her address this spring. In one particularly moving moment at that event, Apollo Gonzalez-Chiles, 33, took to the conference stage and spoke with relief about going for a run on the local campus without fear. He shared that he had been arrested in Oklahoma City in 2015 for sneezing on someone, and that afterward, his local community — including the gay community he’d been part of — had stigmatized him.

“I appreciate you for not looking at me like I’m dirty,” he told the audience, “because I have HIV.”

The diversity of the crowd pointed to the broad swath of people affected by these laws: gay white men, gay black men, HIV-positive women of a range of ethnicities, transgender men and women, parents of people arrested for nondisclosure, heterosexual men and women compelled by the cause, Christians, Jews and Muslims.

A photograph of Kerry Thomas was printed on the back of the conference program, and from prison, he spoke to the packed auditorium about how support from the outside assuaged his loneliness on the inside. He also drew attention to the many others incarcerated by the same laws. “Across the country there are men and women who are fearful,” he said. At the suggestion of Colorado-based advocate Barb Cardell, everyone then stood up. They held their programs with Thomas’ photo facing toward a camera, so that he could see the scene later. In unison, they shouted: “We stand with you, Kerry.”

Activism against HIV criminalization laws is also forming on the world stage. In July, several organizations convened a meeting, called “Beyond Blame,” in Durban, South Africa, just before the 2016 International AIDS Conference there. Steadman attended the event, and spoke about his experience changing the Colorado law, and Thomas again spoke from prison. Various attendees took note that Denmark had suspended its national HIV criminalization law in 2011 while it reviews the policy against current science. It is so far the only country to have done so.

During my visit with him in prison, Kerry told me that although he is continuing to explore his appeal options, he has found ways to mentally cope with his sentence — though to an outsider, they sound only like platitudes that underscore the skewed severity of his punishment. “I can only breathe the current breath,” he says he tells himself. “I can’t do 30 years, but I can do this day.”

And there is that one stubborn fact.

“I didn’t transmit the virus,” he said. “To me, that’s not criminal.”

Jessica Wapner is a freelance writer covering the intersection of health, disease and social justice. Her articles have been published in Scientific American, Slate, Aeon, TheAtlantic.com, AARP, New York, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere. Her first book, “The Philadelphia Chromosome,” was published in 2013.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I learned but the story ,failure to disclosure to partner leads to alot of problems

I am the Amy Davis in this story. Some of the details are half-truths & much of the information, surrounding Kerry Steven Thomas’ original charge, is inaccurate. I know. I was there.

This a terribly flawed article that highly exaggerates the risk of HIV transmission. This journalist did not do her research. There is no significance of viral blips or latent reservoir to risk. Fauci just made his WAD statement of negligible risk. Lazy journalism is tiresome..

looks like the National Institutes of Health and other USG sources will be updating their public positions to better respect the Prevention benefits of *proper* HIV treatment:

https://www.nastad.org/blog/nastad-joins-global-hiv-experts-people-living-hiv-effective-treatment-cannot-transmit-hiv

Failure to disclose to a partner is irresponsible

and immoral.Infecting another is criminal.

Failure to disclose and failure to seek a diagnosis are best immoral to your partner and if infection results is criminal.

It’s unfortunate that an article about the science-ignorant abuses that flow from HIV criminalization should itself distort the underlying science.

This piece powerfully underestimates the Prevention benefits of successful HIV treatment, and worse, it underestimates the risk from untreated HIV+ partners…using totally ad hoc guessing.

The per-act risk of receptive anal intercourse will vary quite drastically based on several factors: the viral load of the HIV+ penetrator, the rigor and duration and lubrication/ overall kinematics of the act. The CDC’S infamous chart of “risk per act” is long debunked…perhaps the author would elaborate a cogent defense of them?

Even more insidiously, the article embraces the intentionally confused objectives of the HPTN 052 study…in an indefensible manner.

HPTN 052 ostensibly sought to investigate the benefits of early treatment…however, it has instead been widely reported as a study of the Prevention benefits of Treatment. Worse still, that reporting has badly confused the issue.

Even in THIS article, the author cites 052 thusly: “Proper treatment is estimated to reduce the HIV transmission risk by 96 percent.”

Wrong. The goal of “proper” HIV treatment worldwide is sustained viral suppression…to achieve consistently undetectable viral load. When THAT state is achieved, the risk of transmission is shown BOTH in HPTN 052, and subsequently in PARTNER, to be several decimal places beyond 99.9%.

HPTN 052 reached the “96%” figure via the inclusion of a serdiscordant couple in whom the HIV+ partner had only recently begun treatment, and had not at all yet reached the universally acknowledged goal of “proper HIV treatment”, aka sustained undetectable viral load.

I hope the author can either properly defend her article or make appropriate edits. She may even wish to revisit the issue of “blips”, which I believe are overstated here…per PARTNER.

There is no epidemiological benefit to downplaying the protective benefits of “proper” HIV treatment, regardless of anyone’s personal fears of loosening sexual mores that may result.

Good work. keep it up.