The Legacy of Undark: Why Science Journalism Matters

Some years ago, on a family visit to Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, my two sons and I signed up for a guided, several-hour ramble downward into the cave. My husband, who is claustrophobic, waited above ground. He refused to even go down the steps toward the shadowy arch of the main entrance.

I love caves though — the sudden reveal of the subterranean world beneath our feet, the hidden labyrinths with their strange water-carved architecture and coppery, mineral-tinted walls. And Mammoth Cave, with more than 400 miles of its underground passages mapped, is like stepping into an endless cabinet of curiosities: caverns spangled with the glitter of quartz or petal-like formations of gypsum, limestone rooms whispering with the rustle of bat wings, the scatter of artifacts left by earlier human visitors years—or even centuries—ago.

Those artifacts tell us that people first started exploring the cave more than 4,000 years ago. The American Indians who then lived in this wooded country lit torches — some of which still remain — to guide them during the hunt for prized minerals in the passages. They left behind not only the burnt cane torches, but occasionally woven shoes and small shells that they’d carried with them. Occasionally, they left their dead here among the cool, quiet rock formations.

It wasn’t until much later, after European settlers moved into Kentucky, that the idea of owning and developing a cave took hold. In the 1800s, the Mammoth Cave system belonged to a series of private owners who offered paid tours to visitors. One of them, a physician named John Croghan, built both an aboveground hotel for visitors and, in the 1840s, an underground asylum for victims of tuberculosis, believing that the soft cave air would benefit them.

Croghan would be proved fatally wrong on that point. A number of his patients died alarmingly quickly, and he eventually died of tuberculosis as well. But the ghost-town buildings of his TB hospital remain in the cave — a reminder of our own imperfect history.

Mammoth Cave was officially established as a national park in 1941 and park rangers today will guide you on a variety of long and short explorations. Our tour walked by the abandoned hospital, filed up steep paths, and then, on a series of carefully hewn staircases, went down, down, down. At the deepest point of our journey, the ranger called us to a halt. He wanted us, he said, to experience true darkness, something rarely available in the light-sprinkled world above. “Stand close,” he said, and then he shut off the guide lamps. Blackness dropped like velvet, so dense and pure that I could not see even a hint of my son hugged up next to me.

Except …

Someone near me gave a faint hiss of impatience. The numbers on my watch, a modern replica of a 1920s design, had begun to glow. Just the faintest circle of blue-green light now disturbed the dark. I slapped my palm over the watch dial. Untroubled darkness returned until the guide gradually brought up the cave lights and we began our return trek toward the daylight above.

But along with my recollections of tiny cave crickets and huge rock formations, I would remember that moment, the eerie mechanical gleam of my watch in the blackness around us. Not light, exactly. Not the untouched night found in the depths of a cave. Just a flicker caught between both: A moment in the undark.

The faint glow of that moment would come back to me some years later when I was researching the story of two pioneering New York scientists, working together in the early 20th century to find a way to detect poisons — and catch killers. The story would eventually become a book called The Poisoner’s Handbook and a PBS documentary by the same title.

Time after time, when people contacted me to talk about the book or the film, they would tell me that the story that haunted them most was not one of grisly murder, but of occupational health. It was the tale of dozens of young factory workers of the 1920s — nearly all women — whose job it was to apply luminous paint to wristwatch dials so that they would glow in the dark, not unlike mine did in Mammoth Cave. The paint they used was made luminous by the radioactive element radium, and it turned out to be a silent poison.

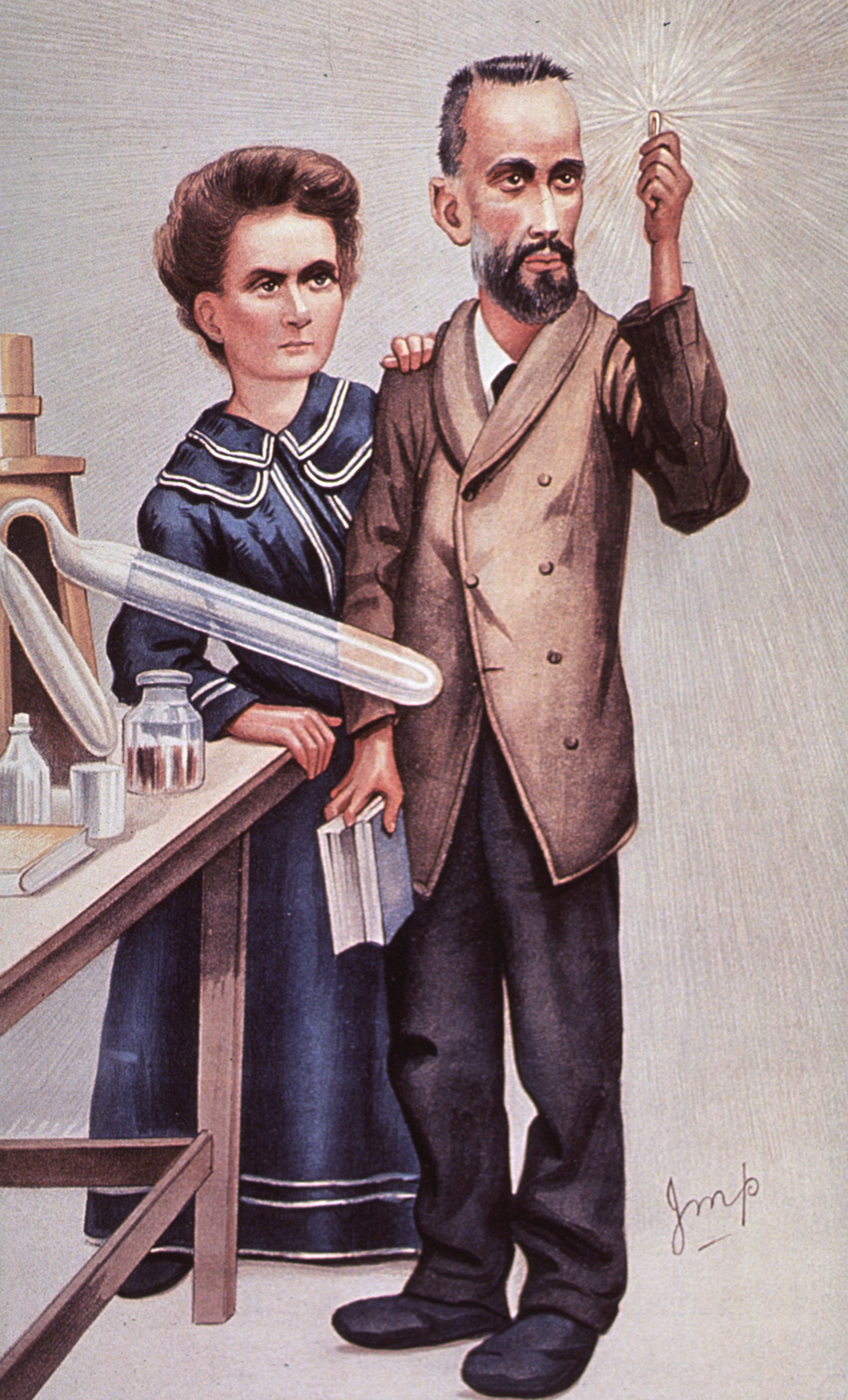

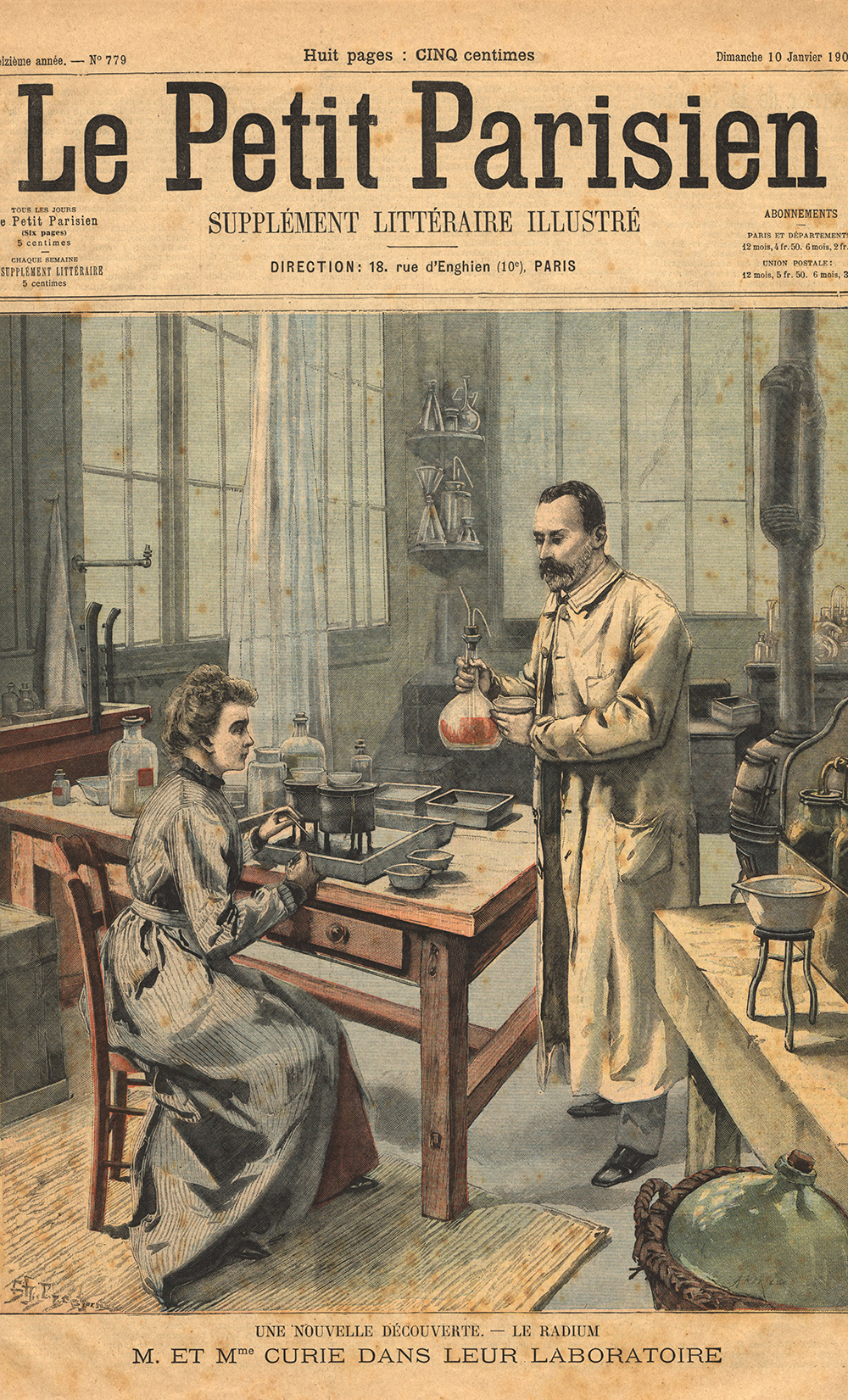

Radioactive elements are ancient but our knowledge of them is far from old. We discovered them in the late 19th century in France, first through Henri Becquerel’s work with uranium, and then through the discovery — by Pierre and Marie Curie — of both radium and polonium.

Marie Curie proudly named the latter after her native Poland. But it was the former that she came to cherish as “my beautiful radium.” It showed early promise in treating tumors, and it seemed to possess a kind of star-like energy — a light that people wanted to use and absorb. Marie Curie carried vials of it, glowing faintly behind the glass, to show off at lectures. To describe its energy, she invented a new word: radioactivity.

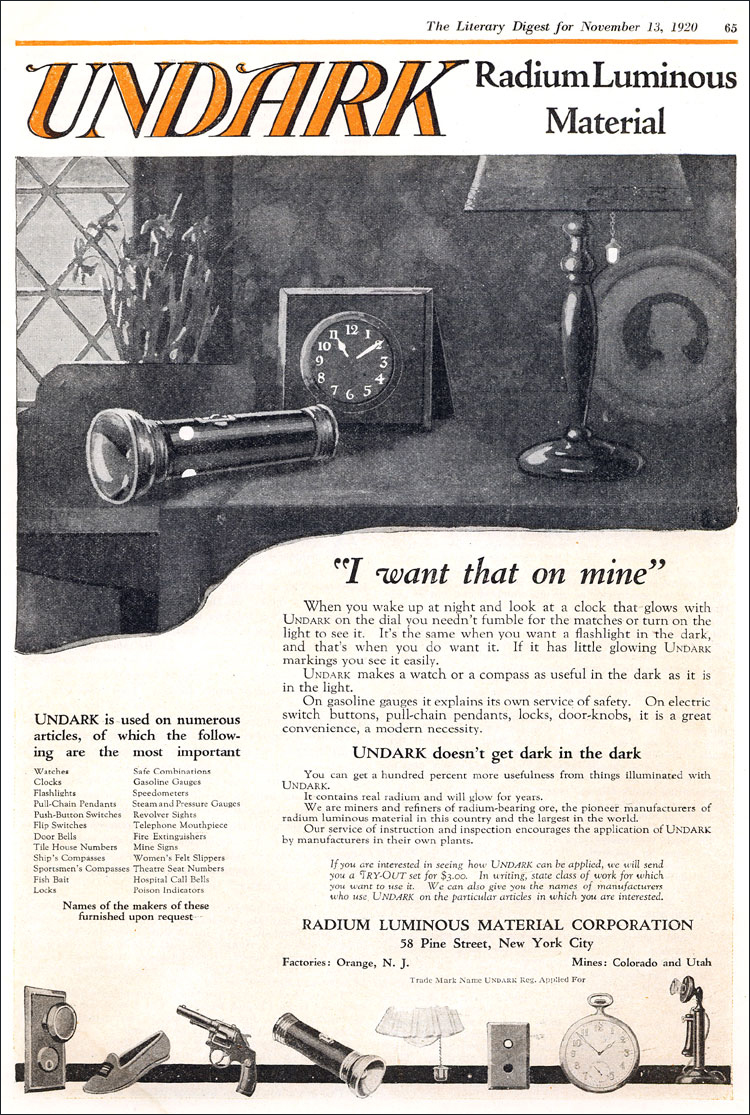

In the way of any discovery, radioactivity beckoned with the dazzle of the new. By the 1920s, consumers could purchase bottles of energy-enhancing radium water, as well as radium-infused candy, soap, condoms and facial creams guaranteed to rejuvenate the skin. Beautifying radium-laced facial powders could be had in a variety of tints: white, natural, tan and African. Newspaper advertisements proudly promised that the application of radium was the next best thing to drinking actual sunlight — an idea enhanced by one of radium’s natural abilities: It could make any number of objects, from clock dials and watch faces to instrument panels, glow in the dark.

Luminous paint was developed commercially during World War I as a product of desperate necessity. Soldiers, crouched in trenches or huddled behind makeshift barriers in the sheltering dark, needed to read dials to safely operate their instruments. Using a flashlight, they risked spotlighting their position. Years earlier, in 1902, electrical engineer William J. Hammer came up with the idea of mixing radium and zinc into paint. The radium excited the zinc atoms, and the result was the faintest blue-green light. Hammer failed to patent the idea, but it was met with enthusiasm during the war —providing enough light to read an instrument, but not enough to betray a position. After the war ended, demand shifted toward stylish watches and elegant clocks for consumers.

“The Power of Radium at Your Disposal” enthused one 1920s newspaper ad, one of a series encouraging Americans to enjoy radioactive materials in their home life. Companies like the New Jersey-based U.S. Radium Corporation hurried to hire workers — mostly young immigrant women — to meet demand, paying them to paint the tiny, lacy numbers on watches and clocks. The women were taught to use their lips to return their paintbrush bristles to a fine tip after each stroke. No one worried about the risks — this was the stuff of cosmetics and health drinks, after all. And the dial painters — or as they would later be called in newspaper stories, the Radium Girls — decorated themselves with the paint, giving themselves glow-in-the-dark smiles and hair that twinkled in the dusk as they walked home from work.

Then they started to fall sick. Their leg bones broke under them as they walked. Their jaws shattered. They developed wasting anemias and other exhausting illnesses. And then they began to die.

Baffled, the New Jersey medical examiner began running tests, and he discovered that those still alive were exhaling radon gas. He published a paper in 1925 titled, “Some Unrecognized Dangers in the Use and Handling of Radioactive Substances.” He also exhumed the body of a dial painter who had died and sent it to New York to be tested. The analysts there reported that five years after her death, the worker’s bones were emitting startling levels of radiation. The research would power a lawsuit against the manufacturer, which explored in horrifying detail the risks of handling (and swallowing) a radioactive element. In 1928, five of the dial painters won a settlement from the U.S. Radium Corporation.

One of them told her lawyer that she expected her share to buy a lot of roses for her funeral.

Remarkably, it would take yet more years, more deaths, and a second scandal involving the lethal nature of radium-based health drinks, before the federal government instituted real safety standards for the handling of radioactive materials.

In the meantime, the radium industry continued to urge consumers to enjoy the benefits of that cool blue-green glow in the night. They marketed it as a very advanced kind of glow — a man-made tool for keeping twilight at bay. Newspaper and magazine advertisements peddled the idea that in a modern, technology-powered world, humans no longer had to rely on primitive torches to find their way through life’s darkened caves. Now, thanks to the modern science of the early 20th century, everyone could enjoy the privileges of “life in the undark.”

When we first started talking about launching a new science magazine under the auspices of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT, we knew what we wanted it to be: A publication that would illuminate the intersection of science and society — that fascinating and wonderfully complicated terrain where research and ethics and public policy collide.

We wanted, I would tell people, to create a magazine that looked at science in both light and shadow.

With that idea in mind, the magazine’s editor, Tom Zeller Jr., and I sat down one day with a list of light-infused research terms. Photon, the elementary particle of light, was on our list, as were Lumen and Candela — international units for measuring luminous flux and intensity. We considered Waves and Wavelengths and even Spark. None of them seemed right. We stared at each other.

“You know,” I said, “there was this word that I came across when I was researching the story of the Radium Girls …”

We never looked any further.

Even today, against the backdrop of a widespread lead poisoning scandal in Flint, or the issues surfaced last month by researchers questioning the federal government’s approval of the drug flibanserin, the story of Undark and the Radium Girls speaks directly to the need for science journalism that keeps the public interest at the core of its mission.

Science — and the technology and innovations that emanate from it — have worked wonders: Millions of people now live longer, safer, more prosperous lives as a result of human curiosity and empirical discipline. But standing in awe of that process is not enough, and on our “About Us” page, we make our mission for Undark plain: “We appropriate the name as a signal to readers that our magazine will explore science not just as a ‘gee-whiz’ phenomenon, but as a frequently wondrous, sometimes contentious, and occasionally troubling byproduct of human culture.”

We aim to make those tensions, which often arise amid the push-and-pull of competing political and economic interests, the target of our long-form investigative and narrative endeavors, which we’re calling Case Studies. By tapping into our deep and talented network of freelance science journalists, we hope to underwrite and publish several such enterprise packages each year. More than half a dozen projects are already in the works.

In between those efforts, we’ll seek to leaven things with a variety of what we call Variables — a mix of thoughtful reviews and essays, penetrating columns and op-eds, and short reported features.

Also in this mix: a new version of The Tracker, a long-running blog that, between 2006 and late summer 2014, critiqued and analyzed science journalism under the auspices of KSJ@MIT. We heard from many in the science writing community that the feature was sorely missed, so you will now find that watchdog function repackaged as a monthly column, authored by long-time media critic and former Tracker blog anchor, Paul Raeburn.

We are also delighted to have Maggie Koerth-Baker launching our “Convictions” column, which will explore the way science manifests — or doesn’t — in the world of criminal justice. And we have already lifted the curtain on an innovative book author series called “What I Left Out,” in which leading science writers offer up a narrative or anecdote that, for whatever reason, didn’t make it into their final manuscripts. The series debuted last month with New Yorker contributing writer Maria Konnikova sharing a story missing from her best-selling book, The Confidence Game. Future installments will include selections from writers like Steve Silberman, Vincent DeVita and Elizabeth DeVita-Raeburn, Sean Carroll, Michael Sims, Emily Willingham and Tara Haelle.

We’ll have multimedia journalism, too — short video documentaries, data visualizations and photo essays, under the rubric of Figures. And we’ll cover the waterfront in a more brisk, discussion-oriented way through our daily blog, called Cross Sections, which is co-anchored by the talented team of Aleszu Bajak, based in Somerville, Massachusetts and Alexis Sobel Fitts in New York. The blog will also include contributions from our Associate Editor, Jane Roberts, as well as a talented team of freelance contributors, including current students from MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing. You might even hear from me or Tom on the blog from time to time.

Finally, for those of you who just can’t find the time to read and see all of the elements we plan to have on offer each month, we’ll deliver highlights — as well as some original reporting — in our monthly Undark podcast, hosted by former New York Times Science editor, David Corcoran and available on iTunes or via your favorite podcasting app. Listen for penetrating interviews with our writers and columnists, as well as commissioned short features from the field.

In sum, we think it is an essential moment to explore science in just this way — holding aloft a steady light as it shapes and transforms, for good or ill, the world around us. Of course, we’re not unique in setting our sights on science, and we join a host of publications, new and old, that we have long admired. But at a time when some of the world’s most pressing issues are rooted in questions of science— from climate change to genetic engineering — we believe there is no such thing as too much journalism.

Perhaps, in the end, we see the colors of our logo — the bright gold of the “UN” leaning hard and eagerly into the graying “DARK” — as more than mere decoration. It’s a reminder that journalism, like science itself, seeks to illuminate the world around us, and where necessary, to cast light into dark shadows so that our lives might be better for it.

It’s in that spirit that we invite you to join us as we learn — together — what it means to live our lives in the bright glimmer of the undark.

Deborah Blum is a Pulitzer-prizewinning science journalist, the Publisher of Undark Magazine, and the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT.