The next total eclipse of the sun, which will trace a slender track across the United States on August 21, is stirring broad excitement among astronomers and the lay public. A similar commotion gripped the nation long ago, when a total eclipse cut a path from Montana Territory to Texas on July 29, 1878, at the dawn of America’s scientific age. The event offered astronomers three minutes of midday darkness in which to study the sun and inner solar system, and it lured a throng of top scientists to the West — to meet the moon’s shadow where it crossed the frontier.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, David Baron shares a story that was left out of his new book, “American Eclipse: A Nation’s Epic Race to Catch the Shadow of the Moon and Win the Glory of the World” (Liveright Publishing).

Samuel Pierpont Langley, director of Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Observatory, climbed Colorado’s Pikes Peak to examine the sun’s outer atmosphere — the solar corona — through the thin mountain air. At lower elevation, in Wyoming, Thomas Edison readied his latest invention — an infrared detector called the tasimeter — to look for heat in the solar glow around the blackened moon. The University of Pennsylvania physicist George F. Barker, armed with a spectroscope, joined Edison beside the transcontinental railroad; elsewhere along the Rocky Mountains, scientists from Princeton, Yale, Johns Hopkins, and the U.S. Naval Observatory aimed their gaze and equipment skyward.

Another team arrived with more than scientific goals in mind. The Vassar College eclipse party, an all-female expedition from that pioneering women’s institution, came to Denver in an era when science was a male bastion. And not just science: Even higher education was deemed risky for the “fairer sex.” In 1873, the prominent Boston physician Edward H. Clarke had warned in an incendiary book titled “Sex in Education” that the recent push for female colleges and coeducation could undermine women’s health by taxing their brains and causing their reproductive organs to atrophy — leading to “a dropping out of maternal instincts, and an appearance of Amazonian coarseness and force.”

Vassar’s professor of astronomy, Maria Mitchell, considered such claims preposterous. As America’s most prominent female scientist — she had gained renown for discovering a comet, which earned her a gold medal from the king of Denmark — Mitchell toiled as a staunch advocate for women’s higher education, and with the eclipse looming she saw a political opportunity. While groups of men — encouraged and assisted by the U.S. government — assembled expeditions to the frontier, Mitchell independently organized her own eclipse party. She invited a crew of Vassar graduates to join her, not only to conduct astronomical studies, but also to serve as role models. These women would demonstrate to the American public that science and higher education were not anathema to health or femininity.

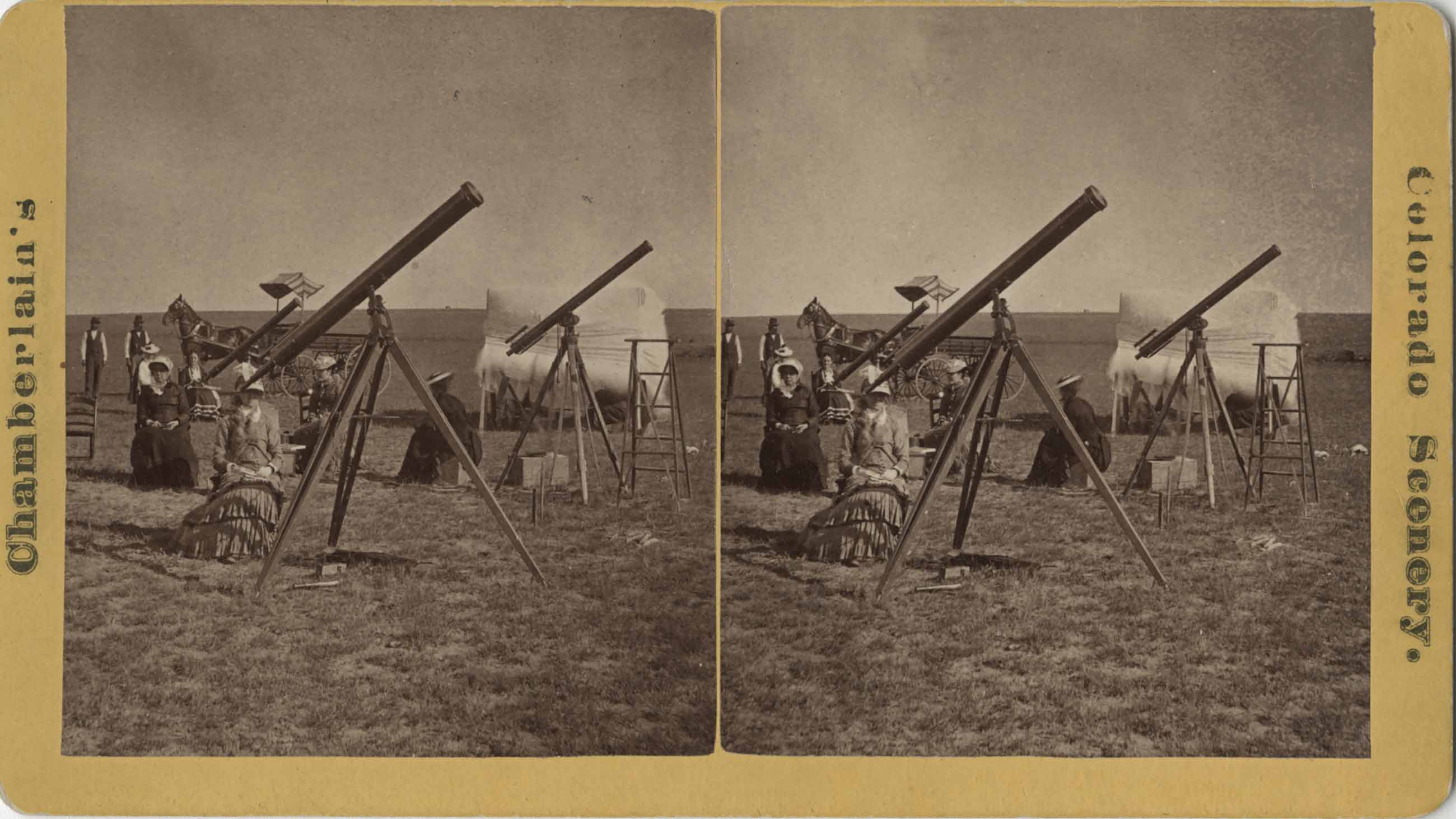

On eclipse day, the Vassar scientists chose for their observation post a hill on the edge Denver. They set out wooden chairs, erected a small tent for shade, and mounted three telescopes on tall tripods. The public watched with fascination. The astronomers in pleated dresses provided “an attraction to the gaping, yet respectfully distant, multitude of masculines, almost as absorbing as the eclipse,” a reporter wrote. “prof. mitchell herself, as with iron-gray curls fluttering under a broad-brimmed Leghorn, she swept the heavens with a four-inch telescope, or directed with native majesty and grace the operations of her assistant nymphs, was a figure, and perfectly commanding.”

The Vassar astronomers also proved inspirational to members of their own sex. “[W]omen of low and high degree throughout the territory turned during that day their thoughts toward the hill…” wrote another correspondent, “for from the mound where the group stood there radiated a light, that sent its rays hopefully into more than one woman’s heart — a heart with longings for study, culture, improvement, that the simple fact of her being a girl had unjustly deprived her of because old prejudices had hedged her path and defined her duties.”

The eclipse expedition achieved its aim, but Mitchell — soon to celebrate her 60th birthday — was feeling her age and was frustrated that she had not accomplished more in her life. “One thing is very clear to my mind — that is, that the world is not yet awake to the needs of women in Education — but whether such as I can awaken it is very doubtful,” she wrote to a friend. And when it came to the needs of women in science, the gap between the real and the ideal remained even wider, as Mitchell was reminded the following summer.

In August 1879, the American Association for the Advancement of Science held its annual meeting in Saratoga Springs, New York, a resort famous for its spas, gambling, and high society. In contrast to the previous year’s conference in St. Louis, which suffered from meager attendance due to a yellow fever scare, the AAAS now attracted a healthy number of attendees. “All agree that it is one of the fullest and largest meetings ever held by the Association,” a journalist wrote from Saratoga. “Among [the participants] are Edison, Maria Mitchell . . . and many others.”

It was not unusual for Mitchell to attend meetings of the AAAS, which unlike the more elitist National Academy of Sciences included female members; in fact, she had been its first, admitted in 1850. Now, at the 1879 conference, a large number of women attended as members or guests. “Their presence, and tasteful appearance, and dress, prove two things,” wrote a newspaper correspondent, “that scientists are not altogether indifferent to female charms and charmers, and that in the feminine mind the working out of abstract lines of thought does not preclude such subjects as Parisian styles and Saratoga requirements.”

Mitchell was not adorned in Paris fashions: She wore her usual Quaker attire, a plain black dress with a white shawl, in sharp contrast to the ostentatious surroundings. One evening, the Local Reception Committee gave a party at the elegant United States Hotel, its gas-lit interior featuring Brussels carpeting, gilt-edged mirrors, and Otis elevators. Mitchell was seen among the scientific illuminati “promenading and whirling over the ball-room floor, while a capital band demonstrated the advancement in the science of music.” On another occasion, she was caught in deep conversation with a prominent Russian astronomer whom she had met on a trip to Europe in 1873. Mitchell appeared to enjoy herself, but she remained frustrated by the meeting’s obvious sexual divide.

George Barker now served as the association’s president, and at the opening ceremony, on Wednesday morning, when he flattered the crowd with this comment about scientists — “Such men are heroes” — it was men who surrounded him on the dais. On Friday evening, at the time allotted for a lecture by one of the association’s vice presidents, the orator was, of course, a man: Samuel Langley, who remarked on the previous year’s eclipse, “In light of our latest knowledge, what, then, is the corona? We do not know.” The next evening’s main event featured three men — Alexander Graham Bell, Barker, and Edison — and a demonstration of Edison’s new loudspeaker telephone, which so amplified his assistant’s singing down the wire that the entire hall could hear the rendition of “John Brown’s Body.” Throughout the meeting, although a considerable number of women sat in the audience, almost none appeared on stage. Of the 136 papers presented, just three were by women.

Mitchell came close to mounting a protest. “I wanted to nominate some woman on some of the [committees] of the Association,” she wrote in her diary, “but my friends assured me that I should do more harm than good.”

In truth, she had undoubtedly done more good than harm in her promotion of women’s rights over the years. Her and her compatriots’ efforts to encourage women’s higher education were paying off; an astonishing one third of students in American post-secondary schools were now female, despite Dr. Clarke’s scaremongering about education’s effect on reproductive health. But Mitchell chafed over how much remained unaccomplished, and one obstacle to women’s advancement in science remained obvious: the male-dominated scientific community itself. She could inspire young women to study astronomy and could teach them the subject, but when they graduated from college, who would hire them? Few careers were open to female scientists. Other than becoming public schoolteachers, they had almost no way to use their training professionally.

Mitchell was thinking a lot these days about her legacy and mortality. On the train to Saratoga, she had spied a Harvard professor she knew. He was reading a popular book on philosophy. It was called “Is Life Worth Living?” Mitchell turned to him and asked, “Is it?”

Mitchell, who died in 1889 at age 70, would not live to witness the full flowering of her effects on American science. Several of her students would, in their own time, rise to prominence in astronomy, and her example would remain an inspiration. One of America’s top astrophysicists in the late 20th century, Vera Rubin, attended Vassar in the 1940s and was asked in 1989 what had motivated her to pursue astronomy despite the societal bias against women in science. “I knew about Maria Mitchell, probably from some children’s book,” she replied. “I knew that she had taught at Vassar. So . . . it never occurred to me that I couldn’t be an astronomer.”

David Baron is a science journalist, author, and broadcaster who has spent most of his 30-year career in public radio. An avid umbraphile, he has witnessed five total solar eclipses across the globe. His previous book, “The Beast in the Garden,” received the Colorado Book Award.