In India, Breast Cancer Screening Goes High-Tech

Like most cancer patients, 65-year-old Lynn Godfrey remembers the exact moment her life fractured irreparably into “before” and “after.” It was a January afternoon 10 years ago, and she had been taking a shower in her home in Pune, in western India. January is a relatively cool, dry month in the city, and Godfrey was enjoying the warm water when she suddenly felt a lump on her right breast.

Worried, she consulted her family doctor, who immediately booked her in for an ultrasound and tissue biopsy. When the results came back three days later with a “malignant, stage two breast cancer” diagnosis, Godfrey was in shock. “I didn’t know anything about cancer,” she recalls. “I had absolutely no clue.” No one had ever told her that growing older put her at greater risk of getting the disease, or that having regular mammogram screenings could help detect it early.

Godfrey’s plight is emblematic of the estimated 150,000 women who are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in India. “Awareness is the main issue,” says Mandeep Kaur, a breast cancer surgeon at Manipal Hospital in New Delhi. Many experts, including Kaur, blame late diagnosis, stemming in part from poor disease awareness, for the alarmingly high breast cancer mortality rate in the country. Godfrey, whose cancer is now in remission, is one of the lucky ones — one in every two Indian women with breast cancer do not survive. Only 66 percent live past five years of being diagnosed, compared to rates of around 90 percent in the U.S., Australia, and other Western countries.

To tackle the problem of late diagnosis, a number of companies have developed new screening devices in recent years. They employ different technologies, ranging from artificial intelligence and machine learning to thermal imaging and immunoassays, but all strive towards the same aim: to make screening more accessible and affordable to women living throughout India. Whether these companies — Niramai, MammoAlert, iBreastExam, just to name a few — can actually lower breast cancer mortality rates remains to be seen, but for now they seem to be making headway with early detection.

“The kind of patients we’re meeting are mostly stage three and four breast cancers,” says Kaur. “I’ve seen women with breast cancers who have badly infected wounds, fungating masses.”

It’s a trend that spans the country, regardless of economic or educational strata. “Surprisingly, both in urban and rural areas, you find people coming in at the later stages,” says Ravi Mehrotra, director of India’s National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research.

And the later cancer is diagnosed, the less likely it is to be successfully treated. In one study, researchers estimated that 10-year survival rates for women in the northern Indian city of Lucknow fell from 75 percent for stage 1 breast cancer patients to 5 percent for stage 4 patients. Early detection offers a solution, but the reality of implementing widespread screening in a country with 1.35 billion people is challenging, to say the least.

Sixty-six percent of India’s population lives in rural areas, where poor transportation links and a lack of electricity are common problems. Doctors are also in short supply, with roughly one radiologist per 100,000 people (the ratio in the U.S. is 10 times higher). Which is why all the new screening devices being developed are battery operated, easily portable, and simple enough to use with minimal training.

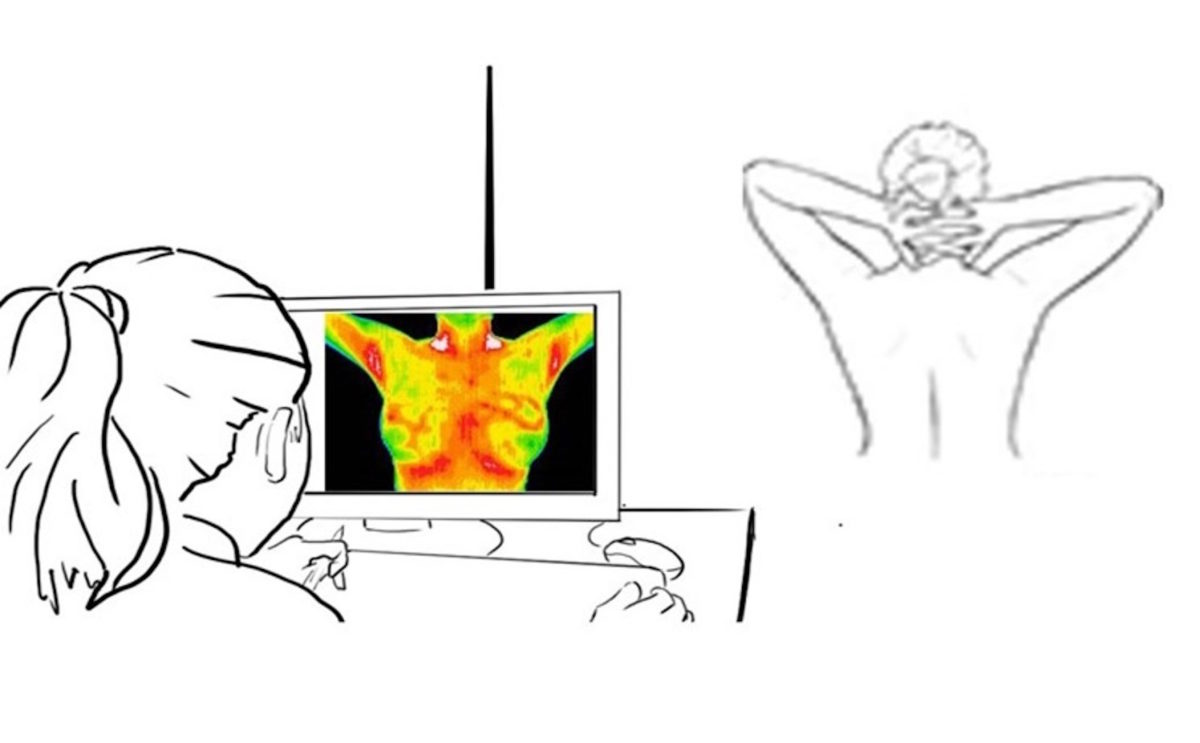

To enhance privacy, Niramai’s screening tool works by capturing thermal images of a woman’s breast using a tripod-mounted camera.

Crucially, they’re also less invasive than mammograms, the traditional tool for diagnosing breast cancer. Not only can mammograms be painful, but they also require women to undress. “Typically, women are very shy. They do not like exposing themselves,” says Nidhi Mathur, co-founder of the company Niramai, which means “being free from illness” in Sanskrit.

To enhance privacy, Niramai’s screening tool works by capturing thermal images of a woman’s breast using a tripod-mounted camera roughly the size of a water bottle. The woman sits alone in a room on a stool before the thermal camera and waits 15 minutes for her body to reach “equilibrium state.” The camera then takes pictures. All of this occurs without anyone seeing the woman’s bare breasts.

The images, each approximately 80,000 pixels, are used to create a heat map of her chest. The company’s software then uses algorithms based on artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze it for abnormal temperature distribution patterns. “Typically, when there is a tumor, there’s higher metabolism, higher blood flow,” explains Geetha Manjunath, the company’s other co-founder. This increases the temperature in the tumor region, resulting in a special pattern that can be detected with the screening tools.

A test with Niramai currently costs about $20, which Manjunath expects to “fall further as volumes pick up.” By comparison, a mammogram in India typically costs between $20 and $50. The technology is currently employed in 11 hospitals and diagnostic centers across five cities: Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore), where the company is based, as well as Pune, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Dehradun.

For clinical screening, the effectiveness of a given device is typically determined by two measures: sensitivity and specificity. “Sensitivity” refers to a test’s ability to correctly identify those with a disease. “Specificity” refers to a test’s ability to correctly identify those without a disease. So far, the company has reported results from two clinical studies, with the most recent showing that Niramai’s rates of sensitivity and specificity are both above 90 percent, significantly better than mammography on both measures. In addition, Niramai was found to be 18 percent more sensitive than its human counterpart at analyzing thermal images for potential malignancy.

Unfortunately, a screening tool like Niramai wasn’t an option for Godfrey 10 years ago. She continues to have yearly check-ups but says she gets “so scared” when she has to do a mammogram because she lost part of her right breast following a lumpectomy. Although she has yet to try Niramai, Godfrey thinks it sounds “very good [because] it’s non-invasive and you’re not getting any pain.”

Others are less convinced. “There aren’t a lot of data to support the use of thermal diagnostics as being better than standard screening today,” says Gilberto Lopes, who studies how cancer control can be improved in low- and middle-income countries at the University of Miami. So far, the two Niramai studies conducted have involved some 300 Indian patients in total, although the company says more trials are currently underway.

Another screening tool being developed is MammoAlert, which will be launched in Gujarat State early next year. “It’s a little lab in a box…a portable system which comes to you,” says Sanjeev Saxena, the founder and CEO of POC Medical Systems, the California-based company that developed the test.

MammoAlert works by performing an immunoassay on a blood sample — just a finger prick is needed, similar to what diabetics do to test their sugar levels. The sample is analyzed for four protein markers known to be associated with breast cancer. “Then we add an algorithm on top of that, which has been trained using deep machine learning and AI, to analyze what is the probability that somebody has breast cancer,” says Saxena. The results are available in less than 30 minutes and are relayed via a smartphone app to the test operator, physician, and patient.

MammoAlert is a test that “can be done in whatever rural community, slums, et cetera, at a very low cost and early,” says Saxena. It has a specificity and sensitivity of more than 85 percent compared with rates closer to 70 percent for mammography in a country like India, he adds, and costs less than $5 per test. While the specific location of the tumor still has to be confirmed via mammography or other methods, the technology has the potential to speed detection of breast cancer in millions of women around the world.

While this sounds promising, more data is needed to confirm that MammoAlert actually benefits patients. Saxena says MammoAlert has been tested in eight clinical trials involving more than 1,000 samples, but the findings are still in publication and therefore not yet publicly available. “MammoAlert is at even earlier stages of development” compared with Niramai, says Lopes. “This is a blood-based diagnostics, and these tests are in the very early stage of studies.”

There’s a third screening tool, however, that has been tested in a wider swath of the population. Since 2015, the FDA-cleared iBreastExam has been used with more than 150,000 women throughout India, as well as in six other countries: Botswana, Indonesia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, and Oman.

iBreastExam is a handheld, wireless device slightly larger than a supermarket barcode scanner. When placed upon a patient’s breast, the scanner’s 16 sensors measure tissue stiffness. Hard lesions — indicative of a tumor — are flagged in real time on an accompanying smartphone app with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 84 and 94 percent, respectively.

The effectiveness of iBreastExam at detecting lesions was demonstrated in a large-scale study involving more than 900 women in Bengaluru. Mandeep Kaur, the breast cancer surgeon, also used the device during a year-long trial at the New Delhi hospital where she was practicing in 2015. The device made a huge difference because “screening is not a very acceptable idea,” she says. Even if a woman initially agrees to it, she may lose interest by the time her appointment arrives four to five months later.

“This tool gave us the opportunity to screen women there and then,” says Kaur. “It gave me that calling point where I can pick up this disease that has manifested already.”

And that’s precisely the aim founder Mihir Shah had in mind when he developed iBreastExam. “I’d like all women to have easy and affordable access to early detection,” says Shah, whose device offers screening for less than $4 per test.

“I think it’s the choices we’re giving women,” says clinical psychologist Rebecca D’Souza of the new screening tools that are emerging. D’Souza works at the Nag Foundation, a cancer charity based in Pune. “We have to be open to newer technologies, especially in countries like India where we’re looking at lower cost.”

“Breast cancer is one of the easiest cancers to solve,” says Niramai’s Mathur. “People don’t have to die from breast cancer.”

Sandy Ong is a freelance science journalist based in Singapore. She covers stories about science, technology, health, and the environment in Asia and beyond.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

In India, even men will feel shy and shameful, going for such a procedure like in memo graph. Understanding that these kind of things are never told or taught by anyone in family, makes it stigmatic and some times a feel of alienation creeps into ones mind. Most of the people (both men and women) in a country like India don’t even realise, what actually they are suffering from, diagnosing it and getting it cured correctly are like long way to go. Not everyone is willing to devote that much of time and most of the times money also. While going through this article I found it very relevant and interesting. Though the alternative diagnosis mentioned are not much clear and easy to grasp for common people. it must mention about How many hospitals or clinics have these kind of facility and what is the minimum price for diagnosis. Anyway thumbs up for making an effort.

Nice article, please tail that in which hospital this is available