For Health and Habitat: Rescuing the Great Lakes

Restoration of the Great Lakes began unofficially in 1969, after the notoriously polluted Cuyahoga River caught fire in Cleveland, near where it empties into Lake Erie. Nearly two decades later, in 1987, the U.S. and Canada signed an agreement creating the Great Lakes Areas of Concern program, which identified 43 Great Lakes watersheds that were most in need of environmental restoration. It also created a process whereby an area can be delisted once its environmental quality has improved.

The Environmental Protection Agency tracks the status of various Areas of Concern. Click the map to zoom or visit the AOC website to learn more.

In 2010, the Obama administration launched the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), which, among other things, provides funds for the Areas of Concern program so that all of the areas left in the U.S. can eventually be delisted. Last year, President Trump called for massive cuts to the GLRI, but Congress fully funded it at $300 million, in a bipartisan effort.

This bipartisan support stems from the economic benefits of environmental restoration. A study by a team of economists released last fall found that every dollar invested in the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative brings more than $3 in additional economic benefits across the region. “It is no longer the economy versus the environment,” said Jill Jedlicka, executive director of Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper, a Western New York nonprofit focused on protecting and restoring the Niagara River watershed. “You cannot have a healthy economy without a healthy environment.”

The Areas of Concern program is a large-scale environmental project carried out largely by local communities — which may account for its longevity and effectiveness. State and local officials, as well as environmental organizations and community groups, work to restore native vegetation, clean up rivers and streams, and enjoy nature in the process. There is still much work to be done, they say, but water quality in the Great Lakes region has improved significantly since the Cuyahoga River fire shocked the region into action.

These photographs were supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society.

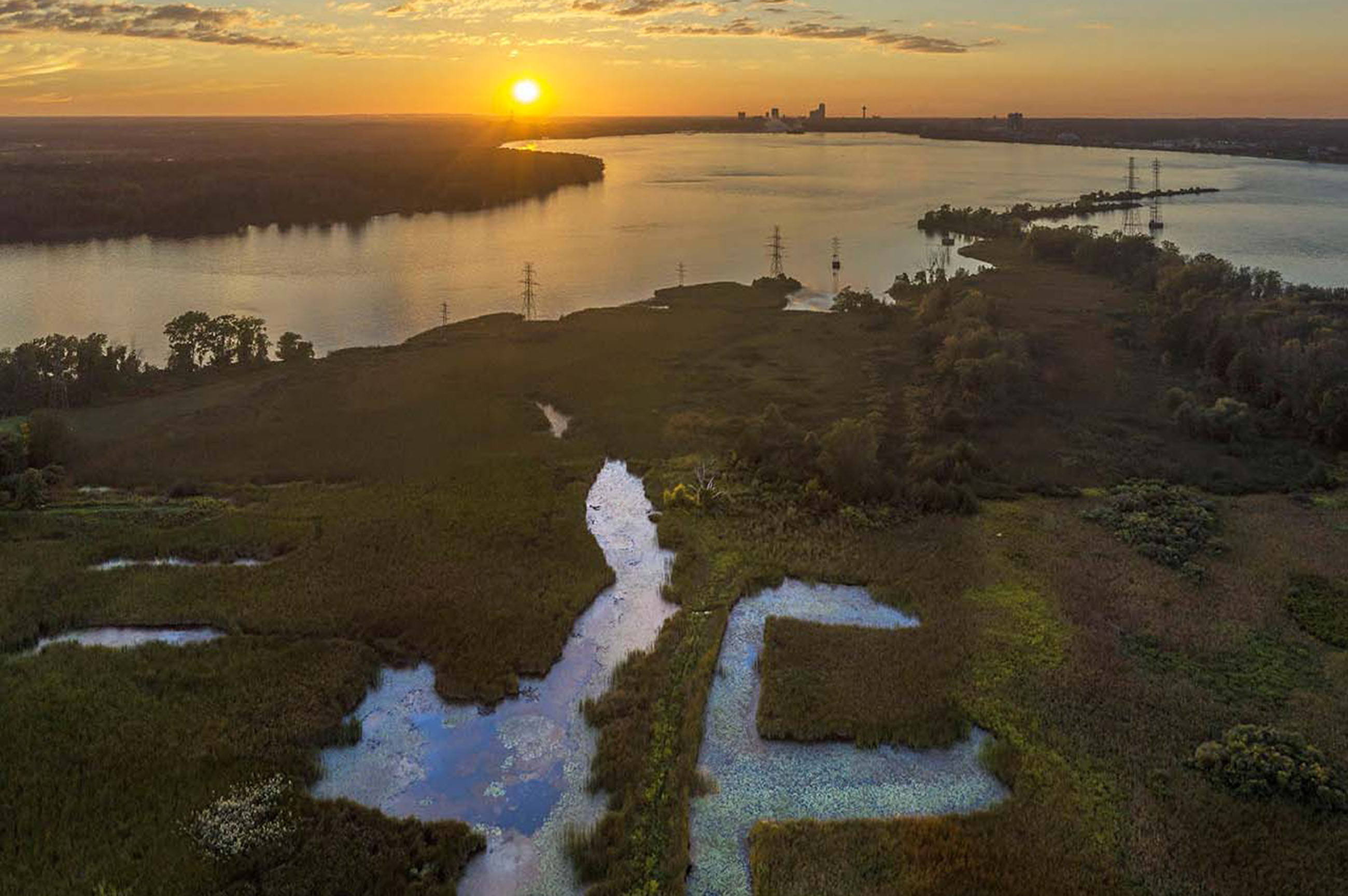

Recovering the Wetlands

There are more than half a million acres of coastal wetlands in the Great Lakes Basin, with roughly 70 percent located in the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. This is less than half of the region’s historical wetlands expanse.

Nurturing Native Species

Close to 200 invasive and non-native species have threatened the historic ecosystem of the Great Lakes region. According to a 2018 progress report, some 135,000 aquatic and terrestrial acres have been brought under control, but far more work remains.

Balancing Power Needs

While the immense water resources of the region have been a boon for power-production infrastructure, dams and electricity generating facilities have taken their toll on the Great Lakes, robbing marshlands of nourishing flows, impacting fish stocks, and occupying shoreline ripe for recreation. Bit by bit, balance is being restored.

Remediating Pollution

Poisoned soil, polluted water, and other fallout from decades of inadequately regulated industrial activity had left vast swaths of the Great Lakes basin a veritable wasteland. But 30 years after the Areas of Concern program launched, signs of recovery are easy to spot — even along the northern Ohio river that became the poster child for Great Lakes blight a half-century ago.

National Geographic photographer Peter Essick is a specialist in environmental themes documenting human impacts of development on the natural landscape. He has photographed stories on climate change, freshwater, high-tech trash, nuclear waste, drought, and ecosystem restoration, and his images have been featured in Time magazine’s “Great Images of the 20th Century” and in “100 Best Photographs of National Geographic.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Excellent, important and vital work! Let’s all help keep up the momentum for positive change.

Appreciate these individual stories being bundled to demonstrate the power of positive momentum. Great to see some specific ones from our corner of the world in northwest Ohio. I am currently leading the preservation and restoration of more than 500-acres of coastal marsh on the Western Basin of Lake Erie. Stories like this are essential to spreading the word to the general public on the importance of wetland and coastal habitats.

Can read more about Standing Rush’s project on Sandusky Bay (Lake Erie) at http://www.standingrush.org.

Peter Essick tells a nice story with a great visual narrative about efforts to remediate compromised environments.