In Costa Rica, a Debate Over Power Lines and Wildlife Electrocutions

In Costa Rica, monkeys travel across unprotected power lines as naturally as they would the vines and branches of the rainforest — and often they have no other choice. As property developments expand and habitat becomes segmented, primates in search of their feeding and resting trees are frequently left to depend on the wires as a bridge to cross roads or cleared land, or to move between isolated forest patches.

Monkeys travel across unprotected power lines as naturally as they would the vines and branches of the rainforest in Costa Rica — at great risk.

Visual: Refuge for Wildlife

It can be a deadly decision. As monkeys thread their way between wires en route, their bodies can form a connection between two parallel wires, completing the circuit and causing a sizzling electrocution. They face additional risk from high voltage transformers attached to the wires. The result can be harrowing: Dead howlers, hanging from an overhead wire, or orphaned infants with electrical burns on their hands, feet, and tails, sometimes with fingers singed entirely off, still clinging to a mother’s corpse.

No one knows how many monkeys and other arboreal wildlife are killed by such electrical infrastructure — though some estimates from the National University of Costa Rica and a 2014 study suggest the numbers run in the thousands per year, with mammals having the greatest risk. And experts say the problem is especially notable in Costa Rica where the vast majority of distribution lines run overhead and where many have been left uninsulated for cost reasons. “Look at where [the monkeys’] home is,” says Vicki Coan, who founded the SIBU Sanctuary in Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula. “Their home is not on the ground. Their home is in the canopy.”

In response to the problem — and to the continued efforts of wildlife activists seeking to force change — Costa Rica’s Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) met last month to sign a “Guide for the Prevention and Mitigation of Electrocution of Wildlife in Power Lines.” The document is described as “the first national effort to work together in proposing alternatives to prevent electrocution” — and the ministry laid out the problem in comprehensive terms: “In Costa Rica, hundreds of animals die each year from electrocution on power lines, many of them suffering serious injuries that limit their activities, significantly impacting populations and ecosystems.” The electrocutions, the statement added, also cause problems for people, including power failures, high costs for repairing damaged equipment, and economic losses related to such events.

The official gesture was welcomed by activists — though it is in no way clear that the government shares their sense of urgency. The proposed electrocution protection guide has just officially been released to the public, and some attendees at the meeting, while heralding progress, said that most of the discussion there involved explaining the roles of the agencies and utilities involved in drafting the document. They also expressed concern that while guidelines recognize the electrocution problem and make recommendations for improved protection of live electrical wires and transformers, they do not require it, nor do they provide any means for enforcement.

“I do not think that there will be significant changes in wildlife electrocution incidents,” said Rafael Ángel Quesada Rodríguez, a former engineer for the Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad, or ICE, which owns roughly half of the nation’s power lines. Quesada, who retired from the company in 2012, has since been an outspoken crusader for better protecting the country’s power lines. The problem, Quesada noted, is that power companies are still not obliged to carry out any sort of prevention and mitigation actions.

The threat of power lines to wildlife is not unique to Costa Rica, of course. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for example, estimates that anywhere from 900,000 to 14 million migratory birds are electrocuted annually on electric distribution lines in the United States alone.

But animal activists like Coan warn that power lines and other electrical equipment in Costa Rica pose a unique threat, arguing that they are now a major killer of not just howlers, but other animals ranging from squirrels to sloths. More poignantly, the problem persists despite Costa Rica’s reputation as a uniquely eco-friendly country. The country’s tourism board routinely touts Costa Rica’s renowned biodiversity, for example, noting that while the nation encompasses just 0.03 percent of the planet’s surface, it is ranked among the “20 richest countries” in terms of species density. Last month, the country gained further attention for a plan to ban fossil fuels entirely.

But that reputation for environmental stewardship, critics say, has been less obvious when it comes to ending wildlife electrocutions. And while wildlife is generally protected by the 1995 Organic Law of the Environment, this law doesn’t explicitly require insulating wires — an easy way to protect wildlife, activists say. At the moment — and despite the proclamation signed last month — there are no laws in Costa Rica requiring utilities to insulate power lines and transformers.

Disagreement over the value of some wildlife — including howlers — is part of the problem. Many people in Costa Rica, one activist noted, regard monkeys as annoying “tree rats” rather than animals worth saving. And the issue has become a source of confrontation between officials and outspoken advocates like SIBU’s Coan, as well as Brenda Bombard, who founded what later became the non-profit Refuge for Wildlife in 1999. Both SIBU and Refuge for Wildlife work to rescue, rehabilitate, and release animals into their natural habitat — at least those who can be saved.

In recent years, Coan and Bombard launched a community-wide effort known as Stop the Shocks to raise awareness and funds for the cause. Laura Wilkinson, the program and media manager for Refuge for Wildlife, says awareness is also driven by experience. “Everyone that witnesses an electrocution and hears an infant howler cry for its mother is upset by the experience and always changes their thoughts on the importance of wildlife protection,” says Wilkinson, who now manages the Stop the Shocks program.

Still, some experts believe that the activists are giving the subject too much priority compared to other issues facing wildlife in Costa Rica. “Electrocution is not and will not be the cause of extinction of any species as relatively few individuals die from it,” said Ken Glander, an anthropologist at Duke University who studied howler monkeys in Costa Rica for decades. He identified cars as a greater threat to monkeys based on his observations. Animals are often forced to cross busy roads after their normal forested corridors are stripped away. Glander believes that reducing clear-cutting — or leaving corridors of trees in place as conduits for wildlife movement — is a far more pressing need.

Coan acknowledges that deforestation is a critical problem, too. But, she says, from her experience in Nicoya, electrocution is likely the biggest killer of howler monkeys. And from the perspective of her nearby animal refuge overlooking Playa Guiones, Bombard agrees. In her area, she says, fast-paced development is driving rapid extension of power lines and driving up electrocutions. They are “the number one killer”, she says, followed by dogs, cars, and the pet trade, and there have been times where she’s been called to power-line related rescues almost daily.

Quesada, the former utility engineer, recommends two key regulatory changes: a requirement that power companies insulate power lines and place protective shielding around transformers and an authorization that they be allowed to recoup some of these costs with rate adjustments. Neither action is currently spelled out in the rules for utilities. And activists worry that without them, power companies will be unwilling to shoulder added costs. ICE’s socioenvironmental coordinator of distribution and commercialization of electricity, Víctor Castro Rivas, says that the cost of installing a fully protected line is more than 23 percent higher than one with unprotected cables, while retrofitting is even costlier.

Activists have been trying to persuade the National Environmental Technical Secretariat (SETENA) to require the protective measures for new lines for some years without any results. But, Quesada says, the Public Services Regulatory Authority (ARESEP), which sets rates, has agreed to at least review the question of allowing utilities to add an environmental surcharge.

In an email message, Carsoth Farrier Soto, an electrical engineer with ARESEP, emphasized that his agency does not set policy. But he said the agency works with power companies seeking new solutions to the electrocution problem. Insulated and underground wiring are far more expensive, he noted, but there are cases when they are the best solution and ARESEP will work with utilities in such situations.

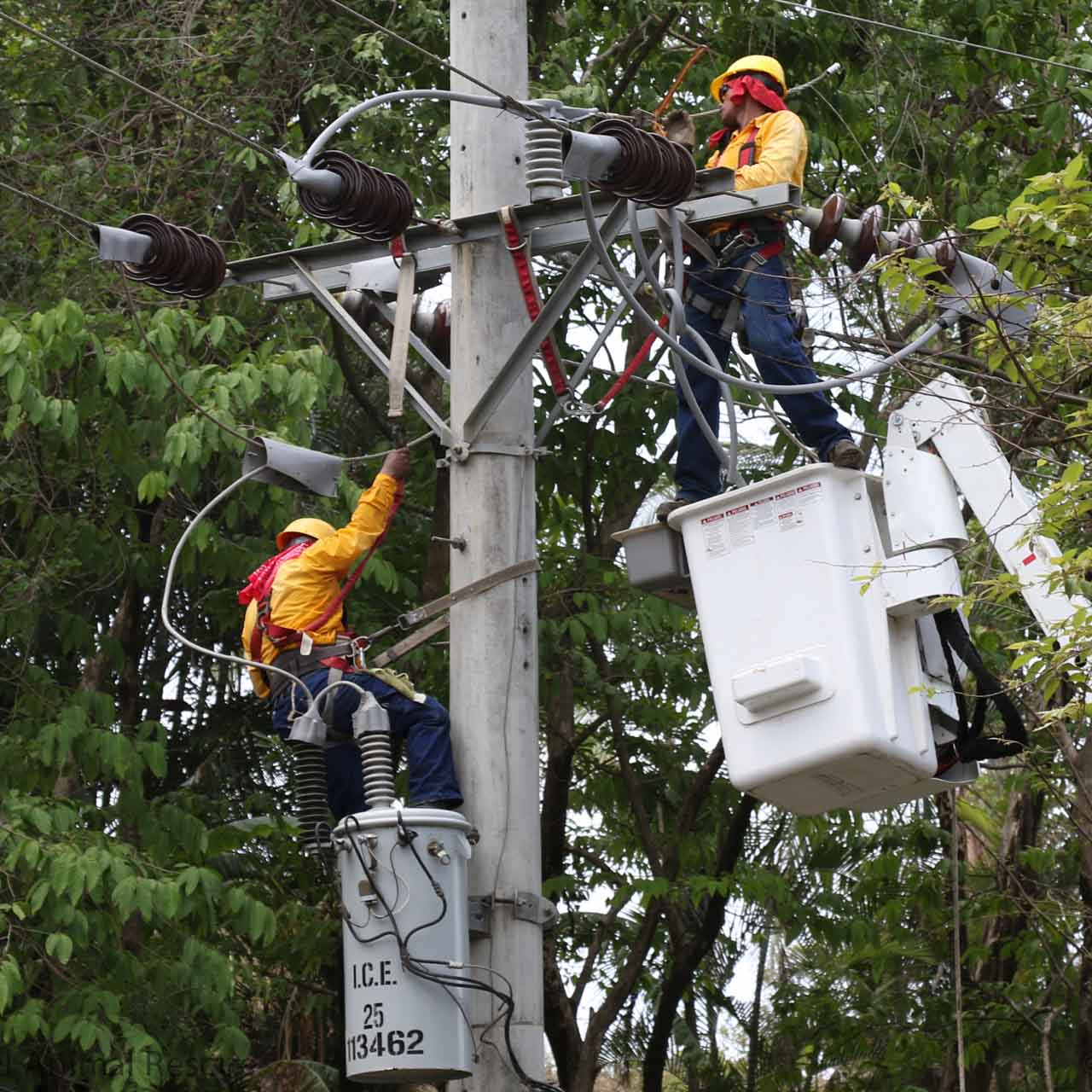

Power companies such as ICE have made some efforts to mitigate problems. For instance, in a 2015 report, the company announced that it had spent some $460,000 installing protective devices across the country to prevent animals from coming into contact with power lines. Rivas says ICE has now insulated more than 280 miles of electric distribution lines in Costa Rica and is making efforts to implement environmental mitigation measures in those places where it is deemed necessary for wildlife.

ICE has also contributed to a series of programs to build new bridges and other crossings for wildlife to use, an effort supported by both Brenda Bombard, director of the Refuge for Wildlife, with their Wildlife Crossings program, which seeks to create safe pathways for arboreal wildlife, and by the non-profit Kids Saving the Rainforest.

Wildlife advocates like Coan and Bombard point out that even with such improvements the vast majority of the network remains unprotected. “I have a lot of respect for what they do,” Bombard says of utility companies, but a more united effort is needed. Like Quesada, they see the best — really the only — answer in government action. They have seen too many dead and injured animals already. Getting a law changed is difficult, Bombard admits. “But we are not going to give up on that.”

Helene Engler is an educator, science writer and editor, and published author based in Austin, Texas. She received her Ph.D. studying tropical butterflies and has written for Nature, The Journal of Chemical Ecology, and The Refresh, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Newton, the wildlife was there long before you and have more right to be there. If you don’t respect that and have issue with paying a little more to protect them from the impacts of human invasion, then perhaps you ought to consider moving elsewhere. That way, you won’t have to pay the higher rates.

We Costa Rica customers of ICE are already paying some of the highest electrical rates in the Western Hemisphere — higher than almost anywhere in the USA. Suggesting that they fix the electrocution problem and pay for it with a rate increase will not be well received and will not foster better feelings towards the “tree rats.”

Thank you so much for writing this very truthful article, the situation is heartbreaking and urgent. It is time for the Government of Costa Rica to enforce the laws that protect wildlife, maybe they could cut the enormous marketing budget for Tourism, and put some of the money towards saving the reasons Tourists want to visit Costa Rica, and increase the field staff of MINAE.