An FDA Weakened by Obama Will Be Conflicted Under Trump

Scott Gottlieb, President Donald Trump’s nominee to become the next commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, sits on the boards of five drug and health care companies. In financial disclosure forms, the physician and resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute has listed 20 companies from which he has taken money.

Gottlieb, who has promised to resign from these boards and recuse himself from making decisions that involve companies in which he has a financial interest, is scheduled to appear for confirmation hearings before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions on Wednesday. But his nomination alone is reflective of the president’s contempt for, and lack of understanding of, an agency that was established to be a citizen’s watchdog over drug companies.

Should Gottlieb ultimately assume the post, he will be the most deeply conflicted leader the agency has seen in its 111-year history, given his background.

“It’s extraordinary, said Michael Carome, director of the Health Research Group at Public Citizen, a consumer rights advocacy group based in Washington. “There has never been anything like it.”

Compounding that concern is the fact that Gottlieb would be inheriting an agency with new and, some critics say, diminished marching orders with regard to the way it oversees the approval of medicines.

Signed into law by outgoing President Obama in December, the 21st Century Cures Act provides the FDA with the power to drop its high standards in certain situations. Among other things, the bill asks the agency to study the possibility of using “real-world evidence” instead of rigorous scientific evidence, when considering certain new drugs for approval. Such real-world evidence can include observational studies, data from drug companies’ lists of patients, and other non-scientific collections of data.

The new law also allows the agency to give approvals on the basis of “summaries” of data provided by drug companies, instead of actual data derived from clinical trials, which FDA reviewers now see and analyze. And the agency is left to police its own use of this new “flexibility,” placing an unprecedented amount of power into the commissioner’s hands.

In meeting with pharmaceutical company executives in January, President Trump signaled his intent to make use of that power. “We’re going to streamline the FDA,” Trump said. Among other promised changes, Trump has pledged to cut FDA regulations by 75 percent or more. He also signed an executive order mandating that all agencies — including the FDA — cut two regulations for every new one they want to introduce, without making it clear how that could reasonably be accomplished.

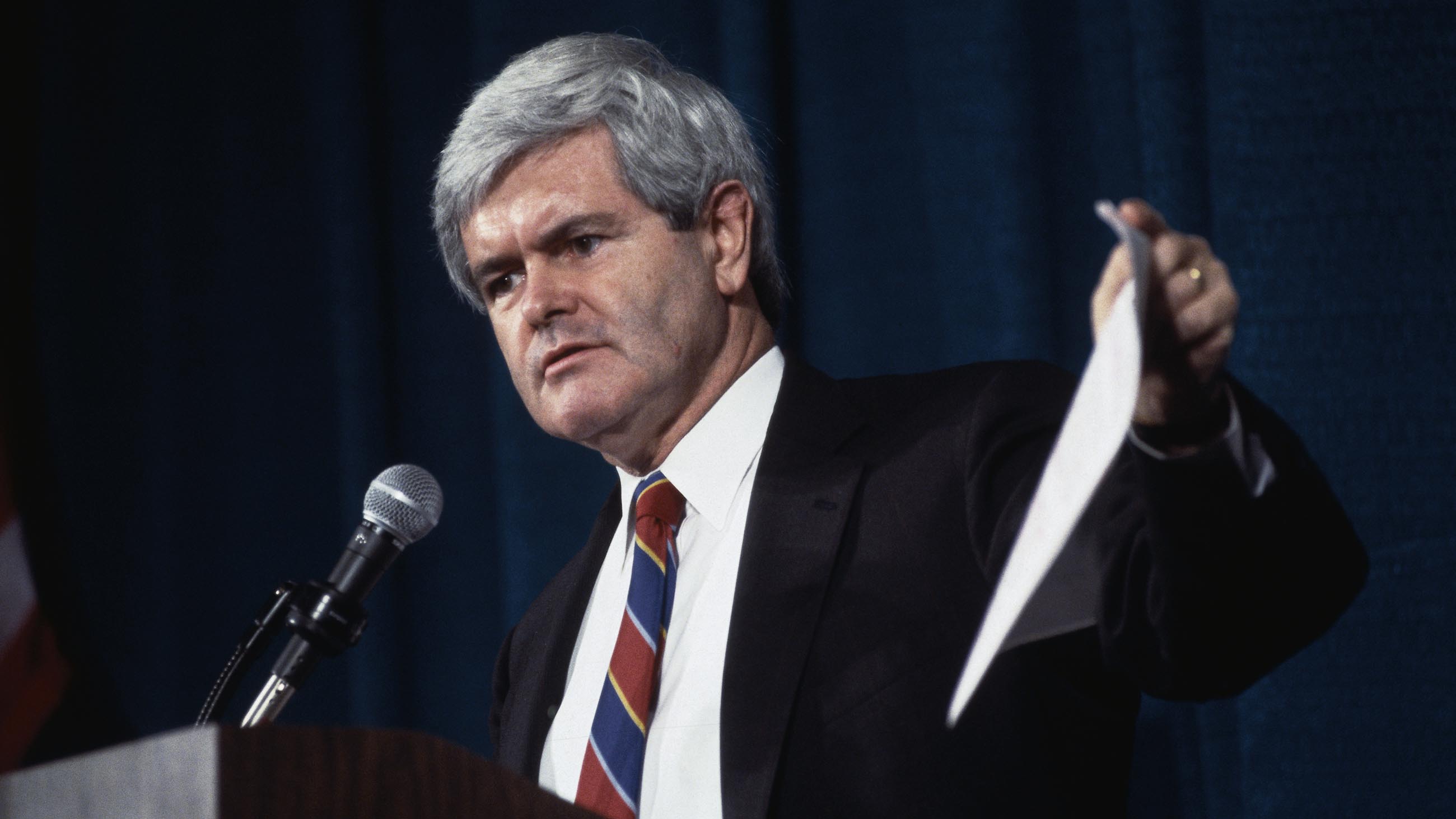

Of course, talk of reducing red tape at the FDA is nothing new in the lexicon of conservative politics. From the Reagan era onward — and even as regulatory bodies around the world sought to emulate the oversight model developed by the FDA — conservative politicians and many drug companies have complained that it takes too much time to develop drugs and get them approved. In the 1990’s, Republicans led by then House Speaker Newt Gingrich sought to drastically scale back FDA oversight and eliminate numerous safeguards designed to ensure the safety of drugs before they reach consumers.

The paradoxical result of those Republican-led efforts? Drug companies panicked and fought the most drastic changes at the FDA, a regulatory body that, whatever its faults, provided drug makers a mantle of safety and credibility among the public. Some companies were so worried about losing that credibility that they even opened a Washington office dedicated to halting the Gingrich-era attack on the FDA.

That’s not to say that drug makers and other industries regulated by the agency have not sought changes. They have long wanted to shorten the time it takes to approve drugs, although Congress has historically refused to provide the sort of funding that would allow the FDA to hire enough staff scientists to make that happen. As an alternative, the pharmaceutical industry has agreed to pay hefty “user fees” to the agency to hire enough additional reviewers to get the job done, and in return, the FDA agreed to establish deadlines for its review processes.

This seemed to have the desired result. While the most deeply anti-regulatory voices continue to decry drug-approval processes that can last as long as 15 years, the fact is that very little of this has anything to do with federal oversight. Indeed, the typical FDA review period has now fallen from three years to less than one, giving the United States one of the fastest drug approval system in the world.

With Trump now promising to scale things back even more, some drug companies — though not all, by any means — are once again worried that Republicans are poised to run roughshod over the fine line between commercial expediency and the public’s faith that the foods and medicines being peddled to them are safe. Indeed, some drug makers — many of whom see the FDA as an imperfect but necessary market equalizer — have openly suggested that some of Trump’s promised changes are worrying.

“We’re not selling Coca-Cola and Pepsi, where patients can taste the Coca-Cola and decide if they like it,” John M. Maraganore, CEO of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, a biotech firm based in Massachusetts, told The New York Times in February. “Our products are lifesaving medicines.”

Industry executives also expressed concern that Trump’s proposals could harm their businesses by making it harder for companies with genuine “breakthrough treatments” to separate their products from phony ones. Daniel Carpenter, a professor at Harvard University who studies the FDA, told The Times that the agency’s role is not just to ensure the safety of a drug. “The underpinnings of belief among patients, payers, even investors, is that somebody out there has tested these things and has shown, with some evidence, that they work,” he said.

Dr. Carome of Public Citizen suggested that the danger is more than just one of perception, and that Trump’s cuts could “fundamentally destroy the ability of the agency to protect patients and consumers from unsafe or ineffective medications and medical devices, hazardous foods and dietary supplements, and dangerous tobacco products, among other things.

“The end result,” Carome added, “would be countless preventable deaths, injuries and illnesses across the U.S.”

As the 21st Century Cures Act and its mechanisms for even faster, even less thorough drug oversight were moving through the Senate late last year — a short stop, it turned out, before landing on President Obama’s desk for his ready signature — the Los Angeles Times columnist Mike Hiltzik described the legislation as “a huge deregulatory giveaway to the pharmaceutical and medical device industry.”

It may also prove to be something of a giveaway to Trump and his FDA nominee, Scott Gottlieb — the latter freighted with unprecedented pharmaceutical industry entanglements, which should be deeply worrying to patients everywhere. Perhaps Gottlieb’s board resignations and promised recusals will help the situation. After all, he is considered a more modest nominee than some of the flame throwers Trump had reportedly been considering for FDA’s top spot — and he has worked for the agency before, including a two-year post as Deputy Commissioner for Medical and Scientific Affairs under George W. Bush.

During that time, Gottlieb also recused himself from decisions on about a half-dozen companies with whom he had worked, though those recusals had a short life: None lasted more than a year.

Phil Hilts is the former director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT. He is also the author of six books and has been a prize-winning health and science reporter for both The New York Times and The Washington Post.