Earth Models Can Predict the Planet’s Future, But Not Their Own

In the 1960s, meteorologist Edward Lorenz was running weather simulations on an early computer system when he realized that a small rounding difference led to extremely divergent weather predictions. He later called this idea the butterfly effect to communicate that small changes in initial conditions, like a butterfly flapping its wings in Nepal, could produce wildly different outcomes, like rain in New York.

But better understanding those initial conditions and how the biological world couples with the atmospheric one can provide better predictions about the future of the planet — from where umbrellas may be most needed in a given season to where electricity needs might sap the grid.

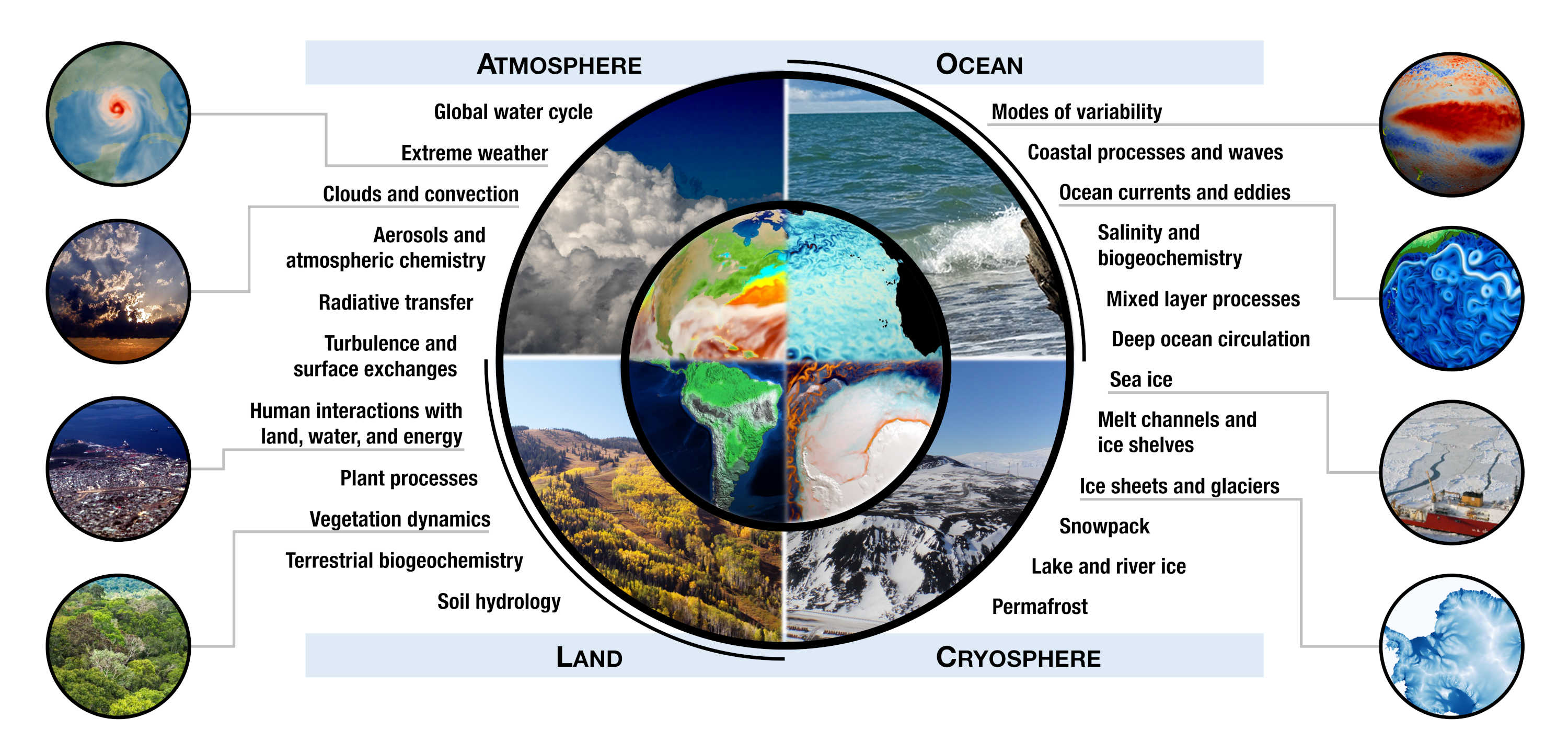

Today, computers are much more powerful than when Lorenz was working, and scientists use a special kind of simulation that accounts for physics, chemistry, biology, and water cycles to try to grasp the past and predict the future. These simulations, called Earth system models, or ESMs, attempt to consider the planet as a system made up of components that nudge and shove each other. Scientists first developed physical climate models in the 1960s and 1970s, and became better at integrating atmospheric and ocean models in subsequent years. As both environmental knowledge and computing power increased, they began to sprinkle in the other variables, leading to current-day ESMs.

“It’s coupling together usually an atmosphere model, an ocean model, a sea ice model, land model, together to get a full picture of a physical system,” said David Lawrence, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Climate and Global Dynamics Laboratory, which he noted was recently changed to the CGD Laboratory to remove the word climate. The models also move beyond the planet’s physical components, including chemistry and biology.

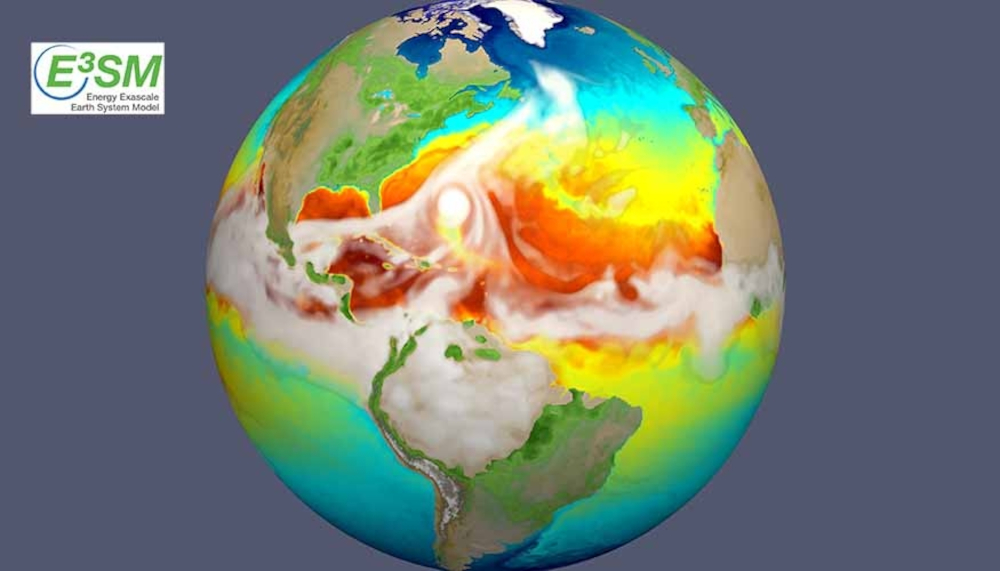

In doing so, ESMs can find surprising conclusions. In 2023, for instance, the Energy Exascale Earth System Model, or E3SM, which was built by the Department of Energy, found that in the simulation, the shapes of cavities in Antarctic ice significantly affect tides many miles away, along the North American coast. That hemisphere-separated connection is just one example of how including an unexpected variable can affect a real-world outcome, and just one of many examples to emerge from E3SM.

Eventually, scientists working on E3SM hope to incorporate enough chemistry, physics, and biology to create a “digital twin” of the planet — modeling Earth in a way true to its real form.

E3SM is one of the world’s premier Earth system models, one DOE has worked on for more than a decade, led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. But as part of budget and programmatic cuts being proposed under the administration of President Donald Trump, E3SM and Earth system research are under threat: The model’s website has been scrubbed of some information, and proposed federal budgets have terminated its future use for climate-related activities — one of its core functions — though it’s unclear how exactly that will play out. Outside researchers could, of course, use the model to study any research questions they desire, provided they could get funding.

E3SM is much finer grained than most such models, providing more tailored and accurate results over a given region. It’s used to predict extreme events, like floods, and unlike most other models, to understand how the climate interacts with the power system — like how that extreme weather may tax the grid, or cause it to falter. Both kinds of studies matter to humans living their lives, in addition to weather wonks.

DOE has already announced about $100 million in funding between 2018 and 2022, according to publicly available statements Undark located, to enhance and improve the model. That sum doesn’t include the resources that would have gone into its initial development. Those more recent investments may now be in question. “There’s nothing definitive,” said Lawrence. But the agency’s proposed budget would decrease both funding and capability.

Meanwhile, experts say that funding cuts could mean modeling abilities migrate overseas, some science may never be realized, and expertise could be lost.

With that toss-off of talent, said Andrew Dessler, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University, countries like China may catch up to the U.S. “It would have been very hard for them to have a more respected scientific organization or scientific system than the U.S. did,” Dessler said. “Our research universities are really the envy of the world, and our government labs are the envy of the world.”

But they won’t be, he said, if the country loses the expertise of those who work in them.

E3SM scientists want to understand how Earth changes over time, and how much conditions vary within long-term projections — like, say, how average temperature may creep up over time, but extremely low temperatures blast Colorado nevertheless. Eventually, these scientists hope to incorporate enough chemistry, physics, and biology to create a “digital twin” of the planet — modeling Earth in a way true to its real form.

That’s a lofty goal, especially since reaching even the current, less twin-like stage took scientists more than 10 years of software development and tweaking. “The models are very big in terms of how much code there is,” said Lawrence, the earth system scientist at NCAR. (Through a spokesperson, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, whose scientists lead the model’s development, declined to comment for this story. “We aren’t able to offer interviews about E3SM at this time,” lab spokesperson Jeremy Thomas wrote in an email; he did not respond to an emailed question about why.)

David Lawrence, a senior scientist at NCAR, led the development of the Community Earth System Model, an early version of which served as a basis for E3SM.

Visual: Courtesy of David Lawrence

Lawrence, though, knows this, as head of a similar project, called the Community Earth System Model, an early version of which served as a basis for E3SM.

Around 30 years ago, scientists at NCAR began working on the community model building on an existing foundation at the agency. In building the community model, they collaborated with DOE researchers, and the agency co-sponsored the model. Later, though, DOE decided to pursue slightly different research priorities, according to Lawrence.

One of those priorities, which they started pursuing in 2014 with the official launch of the project, involved taking advantage of powerful computers. The agency, in addition to studying climate and energy, is also in charge of nuclear weapons. It possesses some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers to simulate those weapons’ inner workings and do science on the side.

DOE, true to its name, also wanted to focus on energy issues. Understanding the planet’s weather and water machinations is critical for, say, knowing how to cool power stations, or when temperatures might tax the grid. NCAR scientists were less focused on energy and didn’t have the same computational bite, according to Lawrence.

And so the two groups split. After around a decade of development, E3SM scientists achieved their main goal in 2023: a terrestrial simulation built for an exascale supercomputer (“exascale” means the supercomputer can do a quintillion calculations per second — millions of times faster than a laptop). After a review planned for later this year, the project is slated to begin its fourth iteration in 2026.

E3SM has been useful to DOE researchers but also to independent ones, who use the model to answer their own burning questions. Environmental researcher Yi Yao, for instance, used E3SM to understand how irrigation affects not just the planet but the people on it. “It’s very important to know that the human activities are altering the system, and it may cause some catastrophic consequences,” said Yao, a postdoc at ETH Zurich who, along with co-authors, published his study’s findings in Nature Communications.

Irrigation, he found, contributes to “moist heat” — essentially, humidity, natural and human-caused. “Farmers who were working in the field, their health — their life even — can be endangered by the moist heat,” he said — not something their employers generally forecast for when irrigating and planning operations. Irrigation, in fact, has been proposed as a strategy for managing heat, by cooling surface temperature — something his study shows wouldn’t be effective.

Importantly, Yao’s work compared results from a variety of ESMs. That’s common practice in the field, and part of why having multiple models is important. “Obviously the physics of the world, the biology of the world, the chemistry of the world, there’s just one version of it,” explained Lawrence. “But how you represent that is so complex that there is no one answer.” Interpolating between different answers helps scientists learn more than they might from a single model alone.

Other scientists have recently used E3SM to find that rising average temperatures can turn farmlands into carbon creators instead of carbon sinks, that intense rains push nutrients into the Gulf of Mexico, and that Pacific hurricanes that first speed west but then turn tail northward decrease the number of forest fires in the American southwest.

“It’s very important to know that the human activities are altering the system, and it may cause some catastrophic consequences.”

But beyond big climatic questions, Earth system models like E3SM are also useful on a more practical level. That’s especially true as scientists work to make them more reliable over time, “so you can really use them for making all sorts of decisions, whether it’s what you’re going to do for your summer vacation to how are you going to deal with sea-level rise in your region,” said Lawrence. How useful and available American ESMs will be in the coming years, though, is a question of money, and its disappearance. Overall, climate research at DOE has been in the crosshairs of the Trump administration. In the skinny budget request for the department’s Office of Science, the administration noted that “the Budget reduces funding for climate change and Green New Scam research,” referencing the proposed Green New Deal, with a cut of more than $1 billion to the DOE’s Office of Science.

According to the DOE’s recent budget request, though, E3SM will continue to exist, but seemingly without one of its primary raisons d’etre. “Any Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM) activities involving climate are terminated,” reads the 2025 budget request, although it is unclear how a climate model can skirt around the climate.

“I do not know to what extent we can say that a topic has nothing to do with climate,” said Yao in an email. “Considering that atmosphere is one important component of the Earth System, it would be very difficult to fully exclude climate.” He did note, though, that some studies are not dedicated to the impacts of climate change but, say, to ecological applications or hydrology. “I do not think it is appropriate to call them having nothing to do with climate but in these cases, they are not used for climate predictions,” he wrote.

The document earmarks “investments on further refinement of the science serving administration priorities,” and details technology that will be used to advance the model, like AI and more powerful computers. It doesn’t specify what goals that AI might serve, beyond enabling higher resolution.

In 2026, the proposed budget decreases DOE funding for Earth and environmental system modeling from around $110 million to $30 million. “Funding will be consolidated under this subprogram to focus on supporting the administration’s highest priority research,” the document notes. It does not specify what those priorities are.

Meanwhile, the National Science Foundation’s budget request notes that its funding of NCAR, which oversees the lab Lawrence works for, will “curtail but continue to support research to refine weather and Earth system models and to better understand the evolution of wildland fires.” The federal government terminated a grant supporting an update to the model, although much of the work was already completed.

And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proposed a funding decrease of around 25 percent, with many of the cuts related to climate change. For many experts in the field, the future of this research can feel unpredictable, like the weather itself.

These cuts have scientists worried globally. In Europe, where Yao is based, what will become of the American ESMs is of great concern. “This is the topic of every lunch table here,” he said.

“It’s quite sad,” he added, “because the USA has always been a leader in the field.”

But it’s hard for U.S. scientists to lead if they can’t describe their work, as some government guidance now forbids certain key terms. Indeed, according to a May report from a local newspaper, an internal publication from Lawrence Livermore noted that the laboratory “has been directed to reword or remove specific words and phrases from all external-facing media, web pages and public-facing communications.” Those terms included “climate change.” When asked by email about the report, Jeremy Thomas, a public information officer for Lawrence Livermore wrote: “We can’t comment on The Independent’s reporting.”

In the view of Dessler, the Texas-based professor, these cuts aren’t just climate-change denial on a scientific basis. “There’s a push to get rid of science that can be used to regulate,” he said — whether that has to do with pesticides or carbon.

“Obviously the physics of the world, the biology of the world, the chemistry of the world, there’s just one version of it. But how you represent that is so complex that there is no one answer.”

But even if the models are curtailed in the U.S., options may exist to keep them sailing — by, for instance, duplicating their capabilities elsewhere. That has happened on the data side before: In the previous Trump administration, people feared the government would delete climate data, so people like John Baez, an emeritus mathematician at the University of California, Riverside who is now working at the University of Edinburgh, backed it up. In the current administration, others have leaped into action, creating archives like the Safeguarding Research & Culture project, which has collected a variety of datasets and publications — from satellite observations of coral reefs to space telescope observations of distant planets — and made sure they’re public and available.

Scientists could theoretically do something similar for ESMs. “You can reestablish that model,” Baez said. “So if some European government decides to take on responsibility for this exascale model, I can imagine that being done.” However, noted Lawrence, to be useful, a model needs to be accompanied by staff with the relevant scientific and technical expertise to run it.

To think that other countries could gather all those ingredients at once might be optimistic. “It’s not like this is the only responsibility that’s something being dropped in the lap of other countries,” said Baez, “and whether they will have the funds and the energy to pursue all of these, it’s actually unlikely.”

Dessler said that if E3SM disappears, or isn’t supported, people could use CESM, which has the same technological origins. Beyond that, said Dessler, other ESMs exist. And they’re still plenty advanced even if they’re not exascale.

To Dessler, the potential obsolescence of any given model is not the issue. “I think the much bigger problem is they’re just going to zero out the work being done at DOE on climate,” he said.

And that zeroing includes people. “What’s really chilling, I think, is the loss of human capital,” he said.

“You cannot generate a scientist out of thin air,” he continued. “It takes years to produce a scientist, and to produce a senior scientist takes decades. And so if you don’t have any senior scientists, you’re screwed for a very long time.”

To understand how that changing variable will affect the planet would likely require a model even more powerful than an ESM.

“I think that’s really the story,” Dessler said.