The Upside-Down World of Crime Statistics

Speaking at an Erie, Pennsylvania rally just two days before of the vice presidential debate, former President Donald Trump made a bold statement: Police should be allowed “one really violent day” to eradicate property crime and theft.

Trump made the claim while presenting the narrative — which has become routine at his rallies — that crime is soaring across the nation, particularly offenses committed by migrants.

The former president, along with several other Republican candidates around the country, has repeated similar claims throughout the campaign season. Violent crime is “through the roof,” Trump said during the presidential debate with Vice President Kamala Harris. In a subsequent radio interview on “The Hugh Hewitt Show,” he suggested that thousands of migrants living in the U.S. without authorization are “murderers.” And most recently, he declared that Venezuelan gangs had “invaded” and even “conquered” the city of Aurora, Colorado.

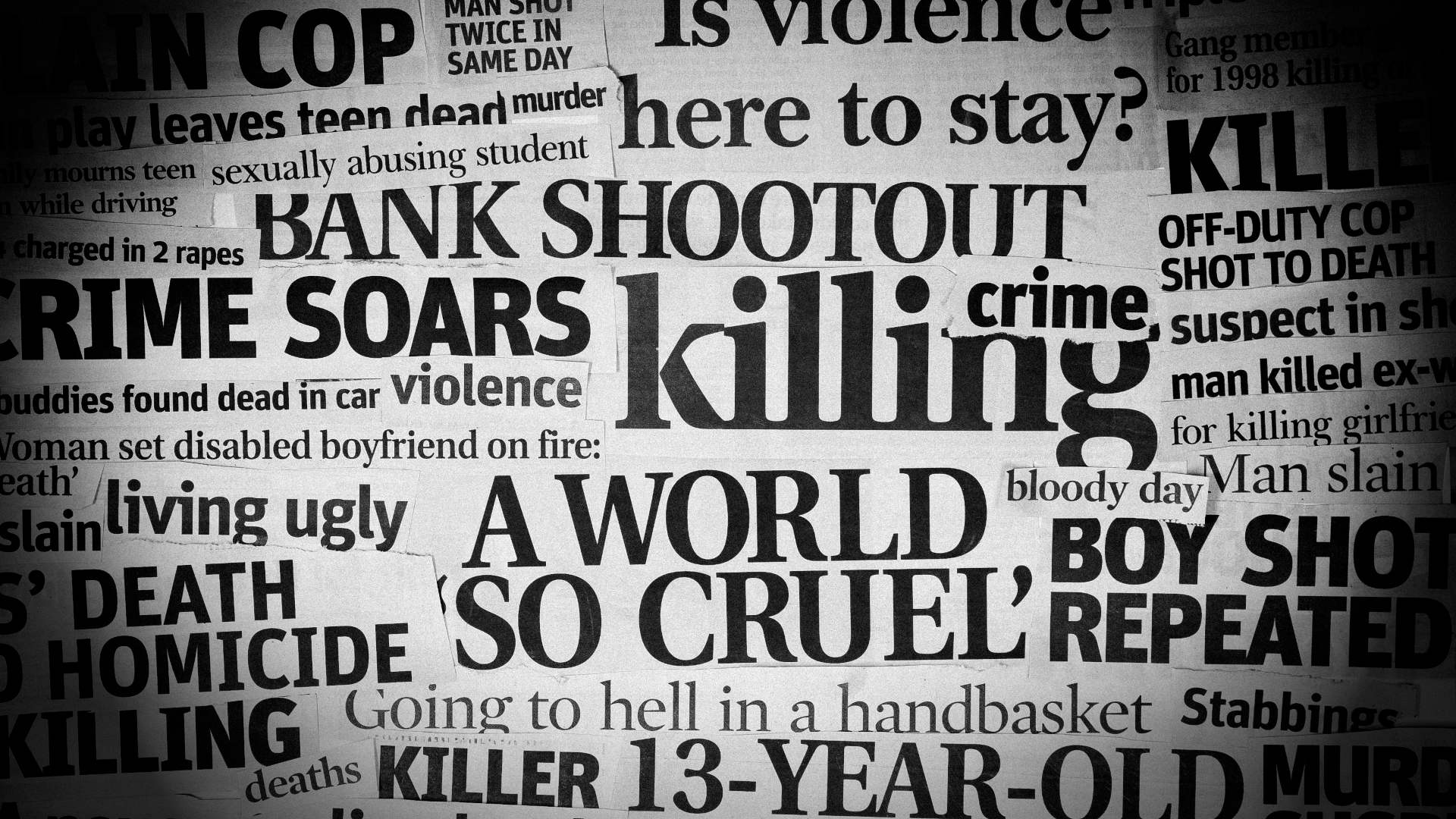

The rhetoric is effective. Several surveys suggest that many Americans still believe crime is increasing, even though official measures show it is going in the other direction nationwide overall. This perception may be, in part, a result of the long-term exposure of voters to local television news reports and political advertisements highlighting crime.

“If you look at the history of the country you know that high crime rates are typically used to engender fear so that they go out and vote for the candidate that claims to be tough on crime,” said Howard Henderson, a criminologist based at Texas Southern University in Houston. “So that’s where we are once again, this kind of conversation about immigration and also violent crime, even though no data shows that immigrants cause violent crime.”

“You have to be able to look at multiple sources and news outlets to make a determination that’s based on multiple perspectives.”

Still, concerns about crime are not entirely unfounded. Some crime rates — such as shoplifting and auto theft — are still stubbornly high according to a recent report from the Council on Criminal Justice. And data on crime victimization from the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics show that only a fraction of many crimes are reported.

As a result, experts say it’s crucial to weigh a wide range of factors to get a full and accurate assessment of the crime problem. “You have to be able to look at multiple sources and news outlets to make a determination that’s based on multiple perspectives,” Henderson said. “Because you and I can look at the same data and come away with different conclusions. Does that mean that both of us are wrong? It just means that both of us have a perception that needs to be considered.”

It’s true that some forms of violent crime sharply increased during the pandemic. The number of homicides, for example, increased by almost one-third in 2020 — the “largest single-year increase ever recorded in the country” since the FBI began tracking national homicides, according to NPR.

After several years of elevated gun violence, murder, and assaults, however, violent crime rates are largely trending downward. Overall violent crime fell 3 percent in 2023 from the previous year, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, which compiles data from about 18,000 police departments and is considered to be one of the more comprehensive national sources of crime statistics. Murder and manslaughter cases fell by almost 12 percent, and the largest decreases in violent crime — about 7 percent — were recorded in cities with more than 1 million residents. In addition, recent reports from the Council on Criminal Justice and the Major Cities Chiefs Association show decreases in violent and property offenses in several large cities.

But the Uniform Crime Reporting Program has its limitations, said Henderson. “Not all crime gets reported to the police, and there are also inconsistencies within how different police departments and jurisdictions report their information, so they lead to a gap.”

This is why it’s crucial to consider multiple sources of data, according to Henderson and Ernesto Lopez, a senior research specialist at the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C. Both criminologists consider the National Crime Victimization Survey to be another valuable metric.

Published annually by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the survey draws on interviews with about 240,000 people from about 150,000 households about crimes that were committed against them — including assaults, burglaries, and robberies — that were both reported and not reported to police.

According to the 2023 survey, only about 40 percent of violent crimes like robberies and assaults were reported to the police. And only one-third of property crimes were reported.

Lopez explained that the Uniform Crime Reporting Program showed that crime decreased slightly compared to 2019. “But,” he said, “when we look at the NCVS, it’s still higher than 2019.” One possible explanation, he said, is that the survey researchers ask only about the prior six months of victimization, which might include criminal activity that took place in 2022.

Lopez is a co-author of the Council on Criminal Justice’s latest report, “Crime Trends in U.S. Cities: Mid-Year 2024 Update,” which collected monthly data on 12 types of crime in 39 American cities from police departments. The reporting period was January 2018 to June 2024, and the results were released several weeks later in July.

“What we essentially find is that one advantage of our report compared to the FBI data,” said Lopez, “is it’s more timely.”

According to the 2023 survey, only about 40 percent of violent crimes like robberies and assaults were reported to the police.

Though his findings don’t measure overall violent crime rates like the Uniform Crime Reporting Program, they show that individual violent offenses have mostly decreased compared to early 2019. In fact, over the past year, crime declined in 11 of the 12 categories tracked, said Lopez, with the notable exception of shoplifting, which increased by 24 percent.

In addition, major crimes involving motor vehicles including theft and carjacking remain higher than their pre-2020 rates. One complicating factor is that clearance rates — how often detectives make arrests — are often very low for property crimes. “Some cities have a 2 percent clearance rate with motor vehicle theft,” said Lopez. “Someone takes the vehicle, it gets dumped somewhere, it gets recovered.”

In the end, statistics may never tell the full story because the researchers who measure and assess crime data often find themselves at odds with the public’s perception of crime.

“Public measures of the fear of crime continue to increase as measured by most Gallup polls,” Henderson said.

According to a 2023 Gallup poll, 63 percent of Americans believe that crime is a serious problem. In fact, in “23 of 27 Gallup surveys conducted since 1993, at least 60% of U.S. adults have said there is more crime nationally than there was the year before,” reports the Pew Research Center.

Some researchers believe the disconnect is, in part, an unintended consequence of repeated exposure to crime reports on television news and crime-focused campaign advertising.

A study led by researchers at Cornell University and first published online in the International Journal of Press/Politics in 2021 found that the longer voters were exposed to crime-focused campaign advertising during the 2016 election season, the more they reported being worried about crime.

“Public measures of the fear of crime continue to increase as measured by most Gallup polls.”

The researchers analyzed two datasets. The first set compiled more than 3.7 million campaign advertising airings for federal, state, and local candidates that appeared in 2015 and 2016. The second dataset measured television viewing habits and policy positions of about 26,000 respondents captured around the same time.

The concerns were more pronounced among Republicans voters than Democrats, said Jiawei Liu, the lead author and a communication researcher, now at the University of Florida.

“What’s interesting to me is what we’ve seen over the last really four or five years is a steady increase in perceptions that crime is on the rise,” said Jeff Niederdeppe, co-author of the paper and a professor of communication and public policy at Cornell. “Which is not empirically true.”