In the 1960s and 1970s, researchers offered financial incentives to patients to get them to lose weight, quit smoking, and abstain from alcohol. To some degree, it worked. But when governmental bodies proffered a pecuniary boon to physicians to move their practice to rural areas, the outcomes were less clear-cut. In fact, new evidence suggests that such monetary incentives barely move the needle.

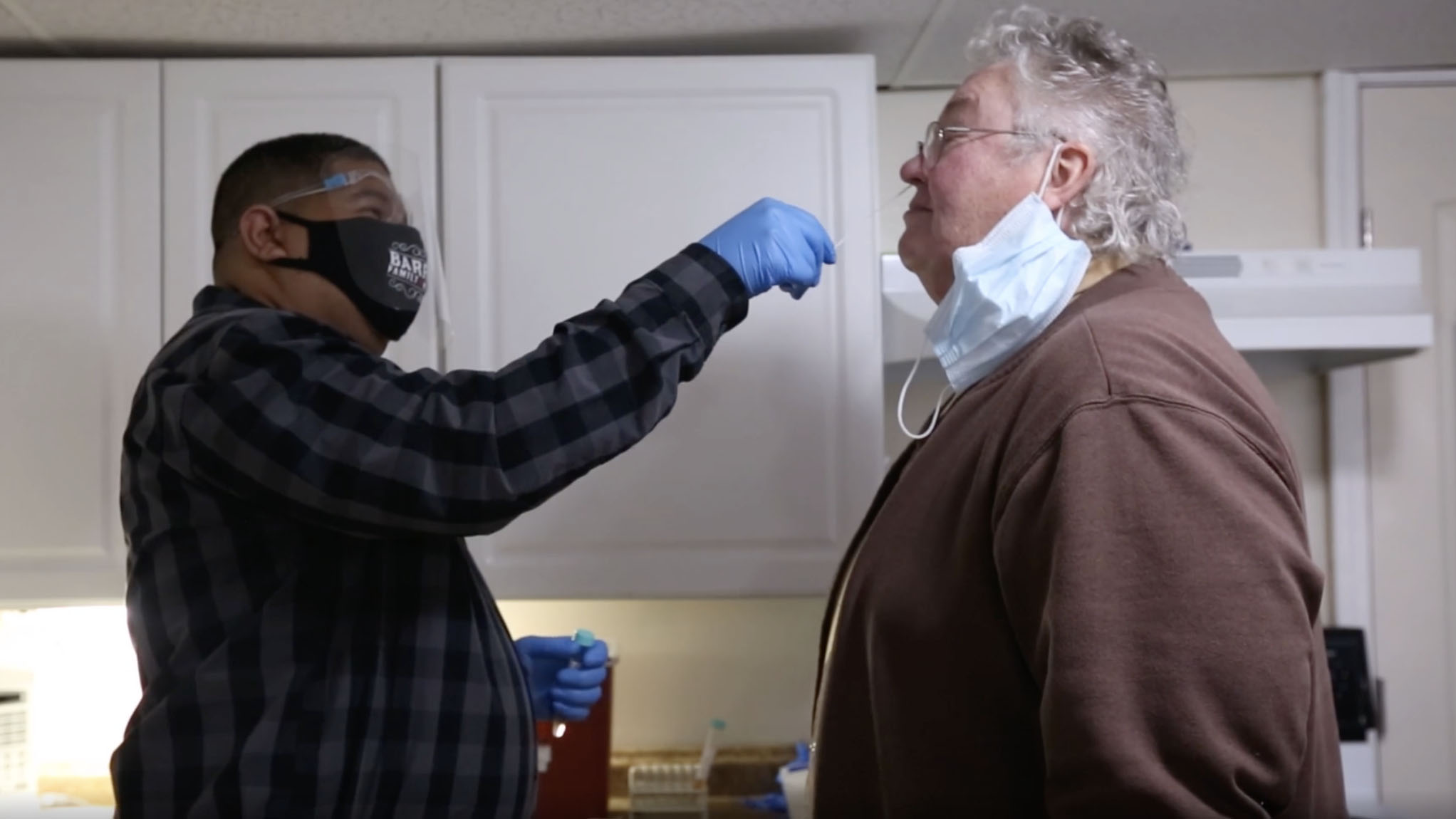

In 1965, as Medicare was being launched, state lawmakers were in the process of identifying regional gaps in the American health care landscape. These places, which were designated under the nationally established Health Professional Shortage Area program, or HPSA, disproportionately lacked medical practitioners and are now areas where a single physician could be tasked to juggle the health of thousands of people. Such medical deserts include more than 5,300 rural areas, in which almost 33 million people face a dearth of primary care services.

To correct that imbalance, the HPSA program trots out various enticements aimed at doctors. Over decades, increased reimbursement rates for patient visits and forgiveness packages for doctors’ gargantuan student loans amounted to a billion-dollar-a-year national effort to shift physicians to underserved places. But researchers reporting in the journal Health Affairs in 2023 found that, despite the bevvy of incentives, neither physician density nor resident mortality changed appreciably after a county gained HPSA status. “Federal officials expanded benefits across time, but we saw no benefits over time,” Justin Markowski, a doctoral student in the department of Health Policy and Management at Yale University and lead researcher on the study, told me. After an initial HPSA designation, 73 percent of counties retained the status 10 years on.

Luring a physician workforce to rural areas is hardly a modern predicament. Over a century ago, the report of the Country Life Commission, convened under President Theodore Roosevelt, briefly mentioned the subject of access to health care. A few years later, Charles Wardell Stiles, an American parasitologist and later a division chief at the National Institutes of Health, elaborated on that idea in his manifesto, “The Rural Health Movement.” He wrote: “In rural districts, medical attention is not as a rule so easily available as in cities, partly because of long distances, partly because of poor roads, partly for other reasons,” adding that “free clinics are practically unknown, district nursing almost unheard of and hospital advantages rare, as compared with these advantages in the cities.”

Health care in rural settings is perhaps only understood when it is experienced. Heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injuries, such as motor vehicle accidents and opioid overdoses, are more likely to claim a rural life than an urban one. (Urban dwellers live nearly two extra years on average compared to their rural counterparts, according to a 2014 study, a gap that continues to widen.) Much of this is the fallout of a convergence of socioeconomic fault lines: poverty, lack of insurance, limited education.

But part of it, too, has to do with being far removed from the regular watch of a primary care physician or the safety net of an emergency department (if a hospital is still around). The reality is not unique to the U.S. Other high-income countries, such as Canada and the U.K., face the similar challenge of supporting the health of their rural populations. Likewise, residents of those regions tend to follow a familiar pattern: older, sicker, poorer, less connected. And doctorless.

As research has shown, incentivizing physician behaviors doesn’t always lead to better outcomes for patients. What makes or breaks an incentive may have less to do with what is being offered, and instead, more to do with what it is trying to accomplish.

According to behavioral science experiments, greater financial incentives motivate greater effort and therefore more often achieve the desired goal. The principle forms the basis, for instance, of Medicare’s merit-based incentive payment system for physicians. But research suggests they’re effective primarily for routine, repetitive tasks, say, quitting smoking — and can backfire for more complex ones, for example, a doctor’s decision to move to a remote area to practice medicine.

Consider a doctor’s decision to make such a move: Often, it is interminably fraught — already hard work is made harder, significant others are uprooted, and certain city comforts and sensibilities may be sacrificed. Physicians, then, must rely on forces internally summoned — autonomy, altruism, competence — to propel them forward. These qualities are harder to define and measure, which make them difficult to meaningfully pin to any reward.

When I left the city for work in a rural hospital, I put those virtues to the test. I was unsettled, initially wading through the steady stream of “hellos,” “good mornings,” and “good nights” from passersby in the corridor, and unsure of how to interact with psychiatric patients who ran a café near their small ward to ease their transition to the world outside. And I was uneasy, at times, with the care we provided — even if patients were appreciative of what they received. The same decisions we fashioned in the city — to get antibiotics delivered at home or to get a surgeon to clear out an abscess — came together with fewer resources, and with doctors stretched hundreds of miles apart.

Strategies to attract doctors to rural areas can take many forms, but it is hard to imagine any being successful without the doctor seeing the benefits of the community in which they reside.

This, however, lent a power to something decidedly tangible. Interactions with patients had an unflinching honesty and tenderness about them. One morning, an older man with anxiety was referred from the emergency department to a senior physician. They ran into each other at the grocery store and at local hockey games; living down the street, the physician would often check in on him. She reviewed his chart, shook her head, and told him to lay off the CBD product he’d been using. “It’s making him forget his other meds!” I remember her saying. In the Venn diagram of patients and providers’ lives, we didn’t occupy the separate realms I was accustomed to, but rather that sliver in the middle that overlapped.

Such moments can’t fit into an ad seeking a prospective physician for a rural practice. Nor can they surely be packaged into a financial payback. But taken together, I feel that they’re worth something. I was reminded how profoundly our lives are affected by a community. This drew me closer to my colleagues, to my patients, and to those long-ago ideals that inspired my drive to become a doctor. Strategies to attract doctors to rural areas can take many forms, but it is hard to imagine any being successful without the doctor seeing the benefits of the community in which they reside.

A connection to a rural identity could be bought with incentives, or it could be learned. Or, I realized, just as importantly, it could be lived through simple and heartfelt things: a teary “thank you,” a firm handshake, or the question, over and again, from patients of your plans to stay. These gestures don’t absolve the system of its responsibility to make positive reforms. But they affirm value and purpose of work that, whittled down by staffing shortages and burnout, can still impact lives our society willfully neglects.

“What we’re doing right now doesn’t work,” Markowski emphasized in our interview about the HPSA program. In a sense, he was right. The problem with relying largely on financial incentives is not suggesting that physicians have only one motivation. It is the misconception that a rural place has only one thing to offer.

Arjun V.K. Sharma is a physician whose writing has appeared in the Washington Post, L.A. Times, and the Boston Globe, among other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Just spitballing over here… but hear me out: has anyone tried building a country club or golf course in these underserved areas? Because in my experience, you’re never going to get decent healthcare if there isn’t some kind of opulence right around the corner.

Medical students in college often marry city girls repulsed by the idea of living in a rural area in their opinion void of “good” shopping, education, entertainment, culture, wealth. Marriage partners not born and raised in the wonderful rural experience will not/cannot adapt. It’s a shame, a missed opportunity for a great family life.

I am a retired nurse. I live in 2 areas that are very different. One is a 10,000 plus tourist town in northern Arizona and the other is a semi-rural community in southern Arizona three miles from the Mexican border. They both have doctor/nurse practitioner/nursing shortages. Both also face a lack of teachers. Yet all of these professions tend to migrate to larger, more rent/own-expensive, more polluted cities with more shopping, restaurants, and entertainment venues.

Many religious groups continue to do missions overseas. I think perhaps there is a real lack of information about how dire the situation is here at home. If people aren’t usually directly affected, they assume there is no problem.