For Many Rural Americans, Covid Highlights a Dearth of Doctors

Before Covid-19, there were no doctors in the village of Otego in central New York. Now there is one. During the pandemic, Mark Barreto quit his job at the Veterans Affairs hospital 89 miles away in Albany and opened a family medicine practice in his basement.

Just 910 people live in Otego, which sits along the Susquehanna River in Otsego County, a pastoral landscape of rolling hills and narrow creek valleys. Barreto lives on a dead-end road, a single street with pastureland on both sides. The downstairs waiting room looks like it could be anywhere in rural America — a row of identical burgundy chairs against a pale beige wall, kids’ art hanging above.

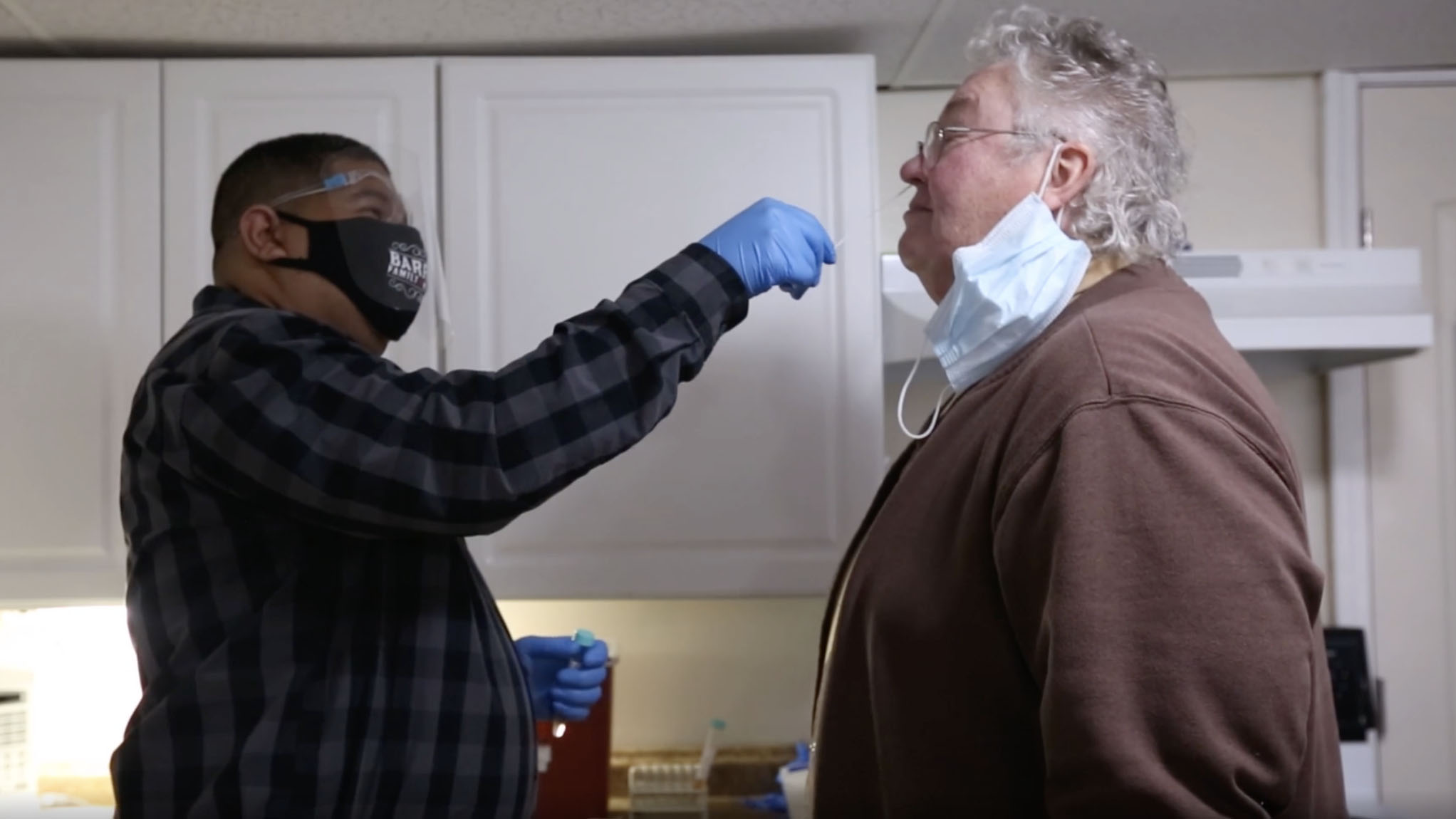

In early December 2021, two of Barreto’s neighbors make an appointment. April Gates and her spouse Judy Tator are both in their 70s. They live around the corner. A friend joined them for Thanksgiving dinner and subsequently came down with Covid. Two weeks later, neither woman has symptoms and both got negative results with at-home tests. But they’re worried. They’ve come to take PCR tests, plus get a blood pressure check for Tator.

“You don’t have to be symptomatic. It’s never bad to get tested if you’ve had a positive exposure,” says Barreto. “Are we being overly precautious? Maybe. But particularly with your cardiac history, you’re at higher risk.”

“I worry most about giving it to someone else,” Gates says. “That’s the biggest thing.”

New York State has an estimated 20.2 million residents. Two years into the pandemic, over one quarter of the population has had Covid — more than 5 million cases and more than 71,000 deaths, according to the state department of health. In the first six months of the pandemic, New York hospitals were overwhelmed with more Covid patients than beds. While they’ve continued to be overstretched, the limiting factor is staffing. A similar situation has played out across the country: Medical personnel have quit in record numbers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Turnover rates were four times higher for lower-paid health aides and nursing assistants than physicians, peaking in late 2020, JAMA reported in April.

The problems are most acute in rural areas that were already chronically understaffed. “We have a health care shortage in the county, in the region,” says Amanda Walsh, director of public health for Delaware County, just across the river from Otego. Walsh and her nursing staff averaged 12 hour days, seven days a week, for all of 2020. “It was an insane amount of time,” she says. The hours only eased after the state established phone banks with remote contract tracers, and Walsh started sending her team home by six, even though the work wasn’t done.

In Barreto’s office, after 40 minutes chatting with Gates and Tator about their health concerns, Barreto swabs both patients, walks them out, and then calls a courier to pick up the tests. While he waits, he pulls up the Otsego County webpage. The Covid dashboard shows 7,235 total cases, and the county recently broke its record for most active cases, at 386. Before December, that number had never climbed above 300.

Barreto swivels away from his desk. In the first months of Covid, he says, medical systems that were already dysfunctional simply fell apart. Commuting to Albany on empty highways, he’d pass a digital DOT sign reprogrammed to read: “Stay home, save lives.” He took the message to heart, wondering, he recalls: “What is my role as a health care provider? Because we’re expected to put ourselves in harm’s way to help people. The problem is we didn’t know what to do to help them.”

For 15 years working in hospitals, Barreto had been dissatisfied with how he saw patients treated. He notes two problems. “One is getting access in a reasonable amount of time. And two is continuity of care,” he says. The ongoing relationship is key, someone who knows your full story, he says, “because that’s what your medical history is, it’s a story.”

When Covid hit, he adds, things only got worse.

With each successive wave of Covid, the disease spikes in cities and then rolls out to rural areas. Towards the second half of 2020, both case rates and mortality rates were highest in rural counties, according to USDA research — especially those only with communities of 2,500 people and under. The study pinpointed four contributing factors: older populations, more underlying health conditions, less health insurance, and long distances from the nearest ICU.

In December, omicron followed the same pattern, peaking in New York City two weeks before it really hit Otsego County, says Heidi Bond, who directs the county’s department of public health. By early January, active cases in Otsego County shot up to 1,120 before the county abruptly stopped reporting the data. The health department was swamped, Bond says, and it was “not possible to get an accurate number with the limited contact tracing and case investigation that is being done.”

Sparsely populated regions like central New York, which have smaller health departments and hospitals, are easily overwhelmed during surges, says Alex Thomas, a sociologist at SUNY Oneonta who studies rural health care. Otsego County has fewer than 10 public health staff working on Covid, and 14 ICU hospital beds. Neighboring Delaware County has no ICUs.

In a 2021 study of New York public health staff, Thomas and his team found that 90 percent felt overwhelmed by work, and nearly half considered quitting their jobs. A survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of about 26,200 public health employees found similar results, with anxiety, depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation among the fallouts. Thomas predicts dire consequences: “We have a serious public health emergency, and there’s nobody to take care of it.”

Covid revealed long-term flaws in the system, and Barreto predicts the U.S. health care system will eventually “collapse on itself.” Bond has a more positive perspective: Health care is stronger now after the trial by fire, largely because “we know a tremendous amount more than we did two years ago” — about Covid, but also about how to help institutions adapt to evolving medical needs.

Before Covid, Bond adds, public health was certainly not a priority at the state or local level. Few elected officials wanted to invest enough or plan for providing robust care for a future crisis. Establishing better partnerships with community organizations let her team overcome these funding deficiencies. “Having those in place moving forward, you know, things will happen much more quickly,” she says, “because we know who to reach out to, to just lend us a hand.”

In Otsego County, dealing with the fallout of Covid became a community effort. Volunteers sent up a local Facebook group to share information and services; it quickly had more than 1,000 members. The local hospital organized an ad hoc “County Health and Wellness Committee” that met biweekly on Zoom. And between 50 and 100 locals representing medicine, public health, and social service agencies, non-profits, and churches exchanged information and ideas and then stepped up to help, says Cynthia Walton-Leavitt, a pastor at a church in Oneonta.

Still, Bond says she worries that public opinion will hamper her department’s ability to prepare for the future. “What I worry about is the fatigue, the kind of mental fatigue of Covid,” she adds. “We can’t let our guard down.”

Before Christmas, Barreto drives about 15 minutes to Oneonta to see his own doctor. Oneonta is the biggest city in six counties with 13,000 residents and has the closest hospital to Barreto’s home practice.

Barreto brings a list of questions, knowing how hard it can be to squeeze out answers from his doctor in the allotted 15 minutes. “There are always two agendas. There’s your agenda as a doctor, why you wanted to see the patient,” he says. “And then there’s a patient’s.”

After his appointment, Barreto grabs breakfast and then heads to his first house call of the day. He says he enjoys making home visits like an “old-time country doctor.” He crisscrosses three counties to see patients, 50 miles in any direction, and gives them his cell number, encouraging them to call whenever they need him. He sees two or three people per day — compared to eight to 15 in former hospital jobs.

Barreto guides his minivan to the interstate and then climbs out of the valley to visit Al Raczkowski, age 88. A former combat medic, Raczkowski still struggles with PTSD, has partial heart failure and some dementia, and requires weekly visits from nurses and therapists through a palliative care agency.

The family has no yard — the hemlocks grow right to the door. Barreto knocks then peeks in. Raczkowski stands in his semi-finished basement wearing a winter coat. He’s not wearing his hearing aid so Barreto shouts: “Al, is Maureen here? Do you know why I came?”

Raczkowski sits down on a futon. “You’re here to check on me,” he says. With that, Barreto gets to work. The room is crowded — firewood and tools jumbled by a woodstove, cardboard boxes, cases of soda and seltzer. A miniature Christmas tree stands on one table, an unfinished instant soup cup on another. Barreto unearths a stool and sets up his laptop beside the soup.

“Do you remember why we’re wearing these masks?” Barreto asks. Raczkowski isn’t sure. “Remember about Covid? We’re wearing these masks to prevent spreading disease.” Raczkowski nods.

Maureen, Al’s wife, appears and shuffles to a seat. For the next hour, the three converse as Barreto performs his examination, mostly asking Raczkowski questions that Maureen answers. How are things with the care agency? “Without their help I don’t even think we would be here,” Maureen tells him. “Living on this mountain for 76 years.” The nurses give Raczkowski showers, check his blood pressure and vitals, and keep him company.

Barreto asks how the medication is going. “It’s OK,” Raczkowski says, “but you’d do better with a bottle of brandy.”

Maureen complains about her husband’s other health care. She drove him 80 miles to the Albany VA to try his new hearing aid, only to learn it had been mailed. As for the new psychiatrist? “She closed our case,” Maureen says. An appointment scheduled for September never happened, she adds, and no one ever answered her phone calls.

After Raczkowski’s appointment, back in his car, Barreto vents frustration: “If you look at a hospital system, and you count the number of medical personnel, versus the number of administration, there’s a skew that shouldn’t be there.” All that oversight, he adds, “doesn’t help your relationship with your patient. It doesn’t help them get the medicine.”

Then he winds back down the mountain road to his next appointment.

Michael Forster Rothbart is an American photojournalist. He is best known for his work documenting the human impact of nuclear disasters.

This reporting project was produced with the support of the International Center for Journalists and the Hearst Foundations as part of the ICFJ-Hearst Foundations Global Health Crisis Reporting Grant.