Interview: NASA’s New Push to Track Unexplained Objects

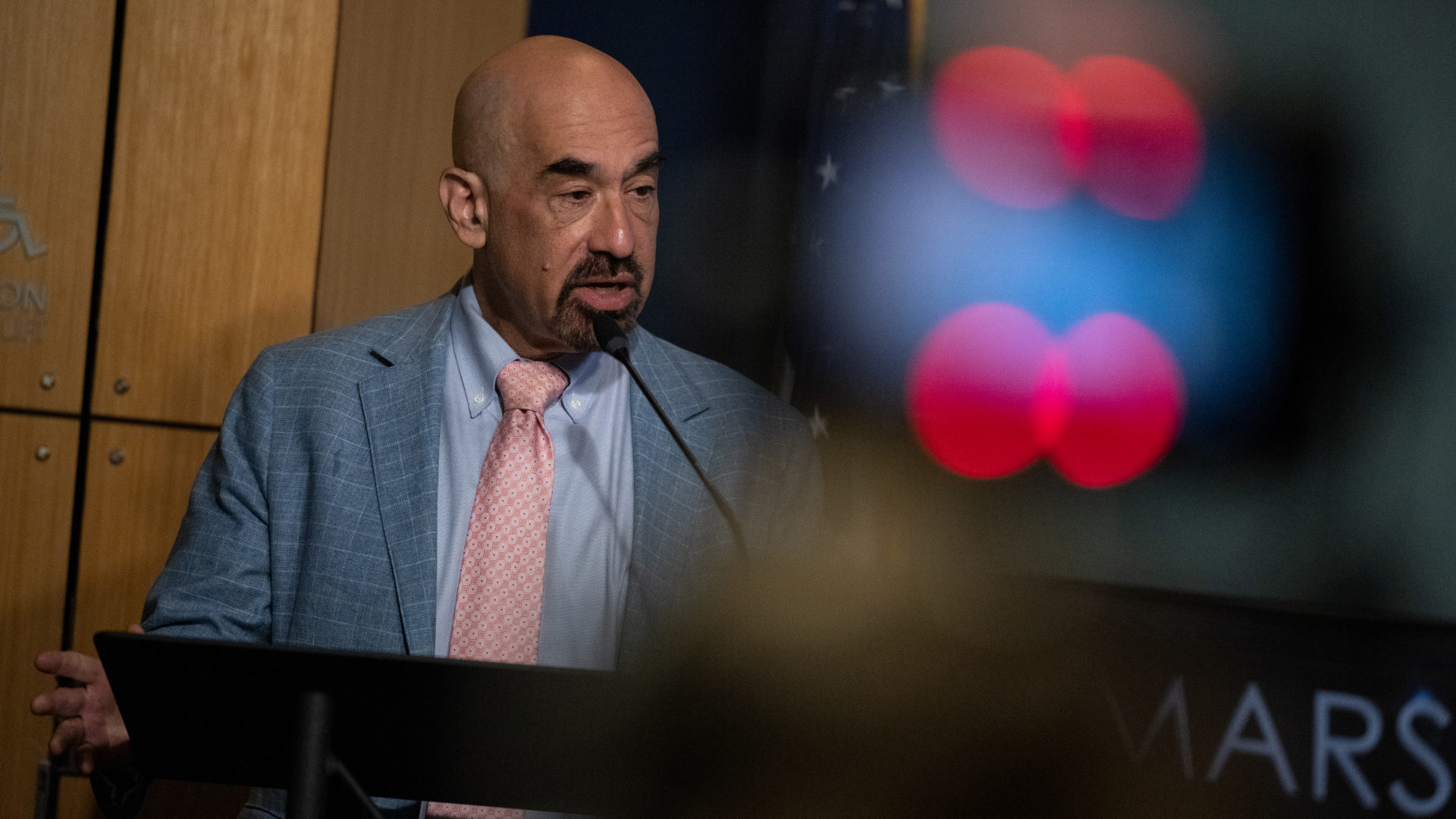

Much of David Spergel’s career has been focused on studying the universe. An astrophysicist at Princeton University, he’s known especially for his research using the cosmic microwave background, the faint radiation associated with the Big Bang, to determine the basic properties of the universe.

He also serves as president of the Simons Foundation, a charitable organization that funds research in math and science. But last year he was recruited to pursue a rather different question: Who or what else might be out there?

It started during a ski trip. Spergel was on the slopes with Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s former head of Science Mission Directorate, when Zurbuchen asked for a favor: He was looking for someone to lead NASA’s Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena Independent Study Team, a 16-member group of independent experts charged with developing what the agency called a “roadmap” for collecting data on UAPs — unidentified anomalous phenomena (previously sometimes called UFOs, for unidentified flying objects).

“It wasn’t something I had any plans to do,” said Spergel. “But NASA has done a lot for my career, and when they ask for something, you go to help out.”

The team issued its final report last month, concluding that although there’s no evidence of aliens having visited Earth, there are plenty of unusual phenomena (some natural and some human-made) in the skies above us. And the more data that’s collected, the report states, the better equipped scientists will be to understand such phenomena.

The same day, NASA announced its new director of UAP research, Mark McInerney, who was previously the agency’s liaison with the Defense Department on UAP matters. With that, Spergel and the rest of his team returned to their regular research. “We have fulfilled our charter,” he wrote in an email to Undark, later adding: “Glad to help NASA with this — learned a lot, worked with good people, no regrets.”

Recently, he discussed the team’s work. Our interview was conducted over Zoom and by email, and has been edited for length and clarity.

Undark: UAP has been called rebranding of the term UFO — unidentified flying object — aimed at reducing stigma. Is it part an exercise in rebranding?

David Spergel: It’s in part an exercise in rebranding. It’s also I think, an exercise in being more accurate. Because many of these things may not be flying. Almost certainly, some of them are floating. A bunch of events are almost certainly balloons, drones, planes. Some are clouds.

There are some events that are not well understood — but some of them, when you look into them, have conventional explanations.

UD: You’re on record as saying that even though something’s unexplained, there’s no reason to think we’re talking about extraterrestrial origins.

DS: That’s right. You start with conventional things first.

UD: People have mentioned the stigma associated with, say, if an airline pilot or a military pilot wants to report something. So what might change going forward? Is the idea just for everything to be more out in the open?

DS: Yeah. And I think the fact that the U.S. military is interested in collecting data on events, the fact that NASA has set up this panel — one of the messages that I think we want to give, particularly to pilots, but to people in general: If you see something unusual, collect data on it, report it.

Now some of this, I think, particularly on the military side, could have military applications. That Chinese balloon that drifted across Canada and the United States — those balloons were almost certainly seen off of Guam, probably by commercial and military pilots, and they didn’t get reported. And in both Ukraine and Russia, they have apps for civilians to report drones. So one of the ways in which the Russians stop Ukrainian drones and the Ukrainians stop Russian drones, is civilians see them fly over, and then there’s an app for reporting information on where it is.

So these are conventional things. But I think, both in terms of potential use for that but also just as a way of educating the public about how we should react when we see something we don’t understand — we shouldn’t ignore it. We should at least report it; collect data on it.

We shouldn’t jump to the conclusion that anything we don’t understand has to be something exotic. But it does mean it’s worth thinking more about. And one of the things we heard from pilots is real fear that they would be ridiculed and lose their employment potentially, for reporting anomalies.

UD: Do you worry that some people will think that if NASA is paying attention to UAPs then it’s lending legitimacy to speculation about aliens and flying saucers?

DS: We tried to walk the tightrope between, in a sense, two communities. You had some people, colleagues, who felt just even discussing this topic was inappropriate, and would bring legitimacy to it. And others, on the other side, who felt there’s a vast conspiracy of hidden alien bases, and unless we disclose NASA’s hidden alien bases, we were covering things up.

UD: Who was saying that?

DS: People on Twitter. The bizarre world of the Twitterverse. I mean, this is a topic which scientists like Avi Loeb have been vocal on. And I hope we achieved this — taking a more balanced approach, where you don’t jump to the most exciting conclusion immediately. But nor do we, as scientists, want to say: “Oh, you see something weird. We don’t want to hear about it.” I think that’s a mistake.

UD: Can you say a bit more about the potential role that the public could play?

DS: So our suggestion is that NASA may do it internally, but more likely, I think, give a contract to some company to develop a smartphone app. Your smartphone starts with a good camera. The software records GPS, it records time, it records local magnetic field, it measures sound of course, gravity.

So you can imagine recording all of that, embedding with the right metadata, watermarking it so it’s not so easily edited and spoofed, and then uploading that to a website. And if you do that, and it’s sorted on GPS position and time, you can ask, are there reports from say four or five different independent observers of something, where they were at the same rough location at the same rough time? And then you’d be able to get 3D — actually 3-plus-1D — information, and figure out how far away the object is, how fast it’s moving, and so on.

Most events will be conventional. But even if what you really do believe, that there are anomalies, you want to get at them. The first step is understanding what’s normal. An analogy I like to make — and this is how I think about how we do machine learning — if I want to find a needle in a haystack, I have two options: Either I know exactly what the needle looks like, and then I use a matched filter that’s optimized to find needles; or I know what hay looks like, and I look for objects that don’t look like hay.

So imagine there’s something that turns out it’s an airplane or a balloon. And in four of the different images, it’s very clearly a balloon. But from one direction with the sun behind it, or in some way, it looks really new. And we learn balloons can look like that, observed in a certain way. And that means when you see something like that in another data set, you’ve learned from that. “Hay can look like that” is how I think about it, with the hay analogy. And you need to build up that data in order to identify what are truly anomalous events.

UD: NASA has always struggled with its budget. So is this avenue of UAP research a good use of public money?

DS: I think this could be done at modest cost. I would not want this to be a big, expensive program. And one of NASA’s jobs is educating the public about science. And this is, in a sense, a teachable moment.

UD: Do you have any idea how much NASA might be budgeting for this, going forward?

DS: The report will inform the NASA planning and budget, but I don’t have any role in their budget planning. Nicky Fox [head of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate] will be the key “decider” on the budget that NASA submits.

Ultimately, Congress sets NASA’s budget. Given the interest in the area, they may even put a line item in. Hard to know, given the level of Congressional dysfunction at the moment.

UD: What odds would you put on there being some intelligent beings out there somewhere?

DS: I don’t know. I like to think about what’s the things we do know. What we’ve learned in the last 20-some odd years is that planets are remarkably common. So we know there’s as many planets, roughly, in our galaxy, as stars. And there are planets that are broadly Earth-like out there, without question.

What we don’t know is, I would say, the biology and the politics. The biology of, given an Earth-like environment, how often does simple life emerge? And how often does simple life become complex? And then the politics of, how long do complex societies persist? Do they destroy themselves? Or do they persist for billions of years? We don’t know.

I look at the fact that the nearest stars are either typically a billion years older than the sun, or a billion years younger. So any life form on a nearby stellar system has likely undergone a billion years more of evolution than us, or a billion years less.

If it’s less, you know, it’s a simple bacteria-like form. And then there’s the possibility of something being more complex — but if there’s something more complex, it’s likely a billion years more advanced than us.

I think of this in terms of Earth: Go back in time to 1923, and you explain to someone today’s society — what our planes and cars and phones are like. And they’d say, “Wow, 100 years; things have advanced, but I understand what society’s like.” Go back to 1023, and you’re a witch, right? You describe flying in the sky and talking to people far away, computers. In 1023, it makes no sense.

Now, I have to imagine the step from 1023 to today isn’t going to be that different from the step from today to 3023. And a billion years is a million steps like that. So if there are aliens that are intelligent, if they’ve made it to Earth, they are so much more advanced than we are that they may represent the difference, the step, between us and bacteria or yeast or something.

So I think it’s very unlikely that there are aliens that come here and are flying vehicles that are technologically similar to what we have today. They are likely much more advanced. And almost certainly, they would be capable of doing things that we would not be able to detect.

I suspect if there are aliens, they either want to be seen or don’t want to be seen. If they want to be seen, we would have seen them by now.