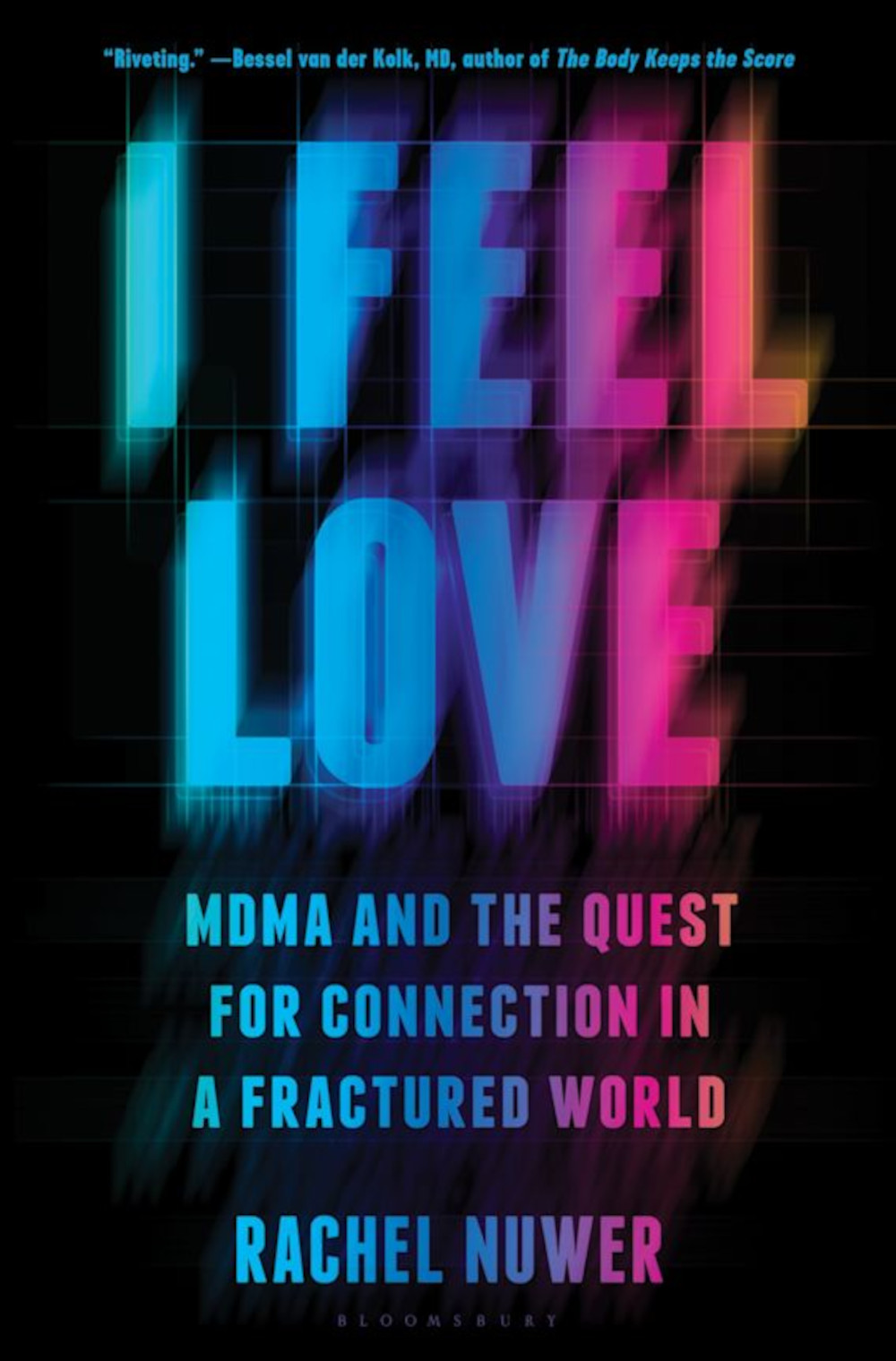

Rachel Nuwer’s “I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World,” is clearly aimed at a broad audience. It will resonate with readers who have experienced MDMA recreationally, probably at a rave, or therapeutically, probably to heal the emotional aftereffects of deep-seated trauma. Or both. But it’s also intended for readers who have never touched the drug, colloquially known as ecstasy or molly. Perhaps it’s especially for them.

“I Feel Love” belongs to a growing family of nonfiction accounts of the fraught history of psychedelics and why, through compelling anecdotes and the latest science, we should reconsider them. Nuwer, a science journalist, chronicles the hopeful story of something both small and large — MDMA, the compound, and MDMA, the drug that’s repeatedly brought humans together across decades, continents, politics, and moral panics. The book is a natural successor to Michael Pollan’s 2018 bestseller “How to Change Your Mind,” which covered the mystical and medical benefits of LSD and psilocybin, and paved the way for a psychedelic renaissance of sorts, Nuwer writes in the introduction, “no such modern telling exists for MDMA.”

BOOK REVIEW — “I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World,” by Rachel Nuwer (Bloomsbury Publishing, 384 pages).

Now, it does. “I Feel Love” is, above all, a time capsule. Nuwer begins with a crucial asterisk: “MDMA, also known as Ecstasy or Molly, is currently an illegal drug.” Today, most journalism around psychedelics is stipulated with this simple fact. Despite their potential to heal, drugs like psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA are still classified as Schedule I, the Drug Enforcement Administration’s highest category for controlled substances with no medical use, with a high potential for abuse. For MDMA specifically, that might be about to change.

A team of researchers that included MAPS Public Benefit Corporation — a company developing prescription psychedelics that arose from the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, which has been advocating for the legalization of MDMA-assisted therapy since 1986 — published a study on MDMA earlier this month. In it, the researchers suggest that MDMA-assisted therapy is an effective approach for reducing post-traumatic stress disorder. The company plans to submit the results to the Food and Drug Administration, meaning that MDMA, when paired with talk therapy, could potentially be FDA-approved as a treatment for PTSD as early as next year.

In many ways, these recent developments feel like the appropriate ending to “I Feel Love.” “Seemingly overnight, MDMA-assisted therapy has emerged in the popular imagination as a miracle cure for otherwise intractable cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans, survivors of sexual violence and childhood abuse, and others haunted by past pain,” Nuwer writes.

I’ve found that to be the case in my own reporting — former cult members and sexual assault survivors have told me, with fervor, that MDMA was the thing that healed their trauma. But through meticulous research, Nuwer demonstrates that the therapeutic potential of MDMA wasn’t, in fact, an overnight sensation.

Her sharp retelling of MDMA’s history takes readers from Germany in 1912, where Merck first synthesized the drug, to the United States, when the Army briefly considered it for controversial research into a truth serum. In one fascinating tangent, Nuwer quotes one of her many sources, Nicholas Denomme, now a postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry at Stanford University, who notes that “it would be mind-blowing to know” that a drug that’s poised to be approved by the FDA for the treatment of PTSD in vets was originally used unethically by the military over 70 years ago.

“Seemingly overnight, MDMA-assisted therapy has emerged in the popular imagination as a miracle cure for otherwise intractable cases of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

From there, Nuwer chronicles MDMA’s unfurling as a party drug, with ecstasy displacing cocaine as the drug of choice on the dance floor. In the early 1980s, MDMA meccas unfurled in Dallas, Texas, where the drug brought together a “level of diversity seen nowhere else in the Bible Belt.” By the late 1980s, it was in use throughout the U.K., where it allegedly reduced violence at football matches; it also exploded onto the Dutch party scene, and quickly after, made its way to in Berlin. Today, of course, molly — MDMA’s modern moniker and a nickname for “molecule” — powers music festivals around the world.

While most of the recent science around MDMA focuses on its therapeutic benefits — for PTSD, addiction, depression, anorexia, social anxiety in autistic adults, and traumatic brain injuries, for example — Nuwer shrewdly points out that relatively little research has been directed toward MDMA’s recreational use. “The largest single population of Ecstasy users is probably still young people in music-focused environments, and for many of them, these are among their most treasured and beautiful life experiences,” says Kevin Balktick, the founder of Horizons, an organization that runs a large annual psychedelic conference.

Those treasured and beautiful life experiences are recorded across a spectrum of characters throughout the book. A DJ describes the feeling MDMA invokes as “almost like a religious experience,” one where ecstasy tablets become sacrament. A Vietnam veteran remembers it as an “electric shock to the system.”

A couple in their 70s, who have done MDMA dozens of times, say it’s the “antidote to feeling old: we become ageless for a day.” My favorite descriptor is one Nuwer offers from a friend: “What the rush of joy, elation, and love would feel like if you were suddenly reunited with a good friend you hadn’t seen in years, and you stayed up all night talking because you were so happy to see each other.” (It’s funny; The first time I personally took molly, with a close girlfriend, we were locked in conversation for hours, giggling until the sun came up.)

At several points throughout the book, it starts to feel as if MDMA can do it all. Through Nuwer’s interviews with scientists and activists, we learn that MDMA can solve marital problems, help cancer patients cope with their realities, save years of therapy, and all but eradicate negative emotions. But Nuwer is careful to cut through those shaky claims with breakneck precision, providing an important bulwark against casual hype.

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Nuwer argues throughout the book that the most common effect of MDMA is imparting a feeling of connection. Perhaps MDMA is simply a lens through which to look at human behavior, as it mirrors our innate desire to tinker with consciousness. “Because our tendency to seek out consciousness-altering experiences has withstood the selective pressures of evolution, scientists surmise that there must be benefits,” she writes. “Some of these benefits probably relate to survival: caffeine to keep us alert and enhance our abilities, opium to relieve pain, alcohol to bring us together.”

“But,” she continues, “evidence also indicates that our use of psychoactive substances has shaped us in subtler but perhaps equally powerful ways, by helping mold the customs, beliefs, and traditions that have made our species what it is today.”

Will MDMA save the world? Nuwer denounces that idea in her introduction and repeats the sentiment in many corners of the book. Instead, “I Feel Love” offers a foundation of knowledge that’s perhaps needed to push MDMA to the forefront of mental health through a nonalarmist, honest perspective.

From there, Nuwer lightly suggests that MDMA might potentially be a solvent for the drivers of loneliness and disconnection — caused by the pandemic, our ever-widening political divide, and the isolation of social media — on the individual level. Either way, you may well be tempted to take MDMA immediately after reading this book.

Taylor Majewski is a San Francisco-based health and science reporter whose work has appeared in MIT Technology Review, STAT News, Vox, Cosmopolitan, and elsewhere. She is currently a fellow at The USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It was MDA aka: Uncle Tom’s Brew…or Maddog in the 1970’s. Produced by a character called Uncle Tom from Winston Salem, NC. It was much stronger and not exactly the same thing as MDMA. You could eat it but we mostly injected it. We sold it for $35/$40 a gram. Amazing stuff.

What’s next? Legalizing PCP and LSD?