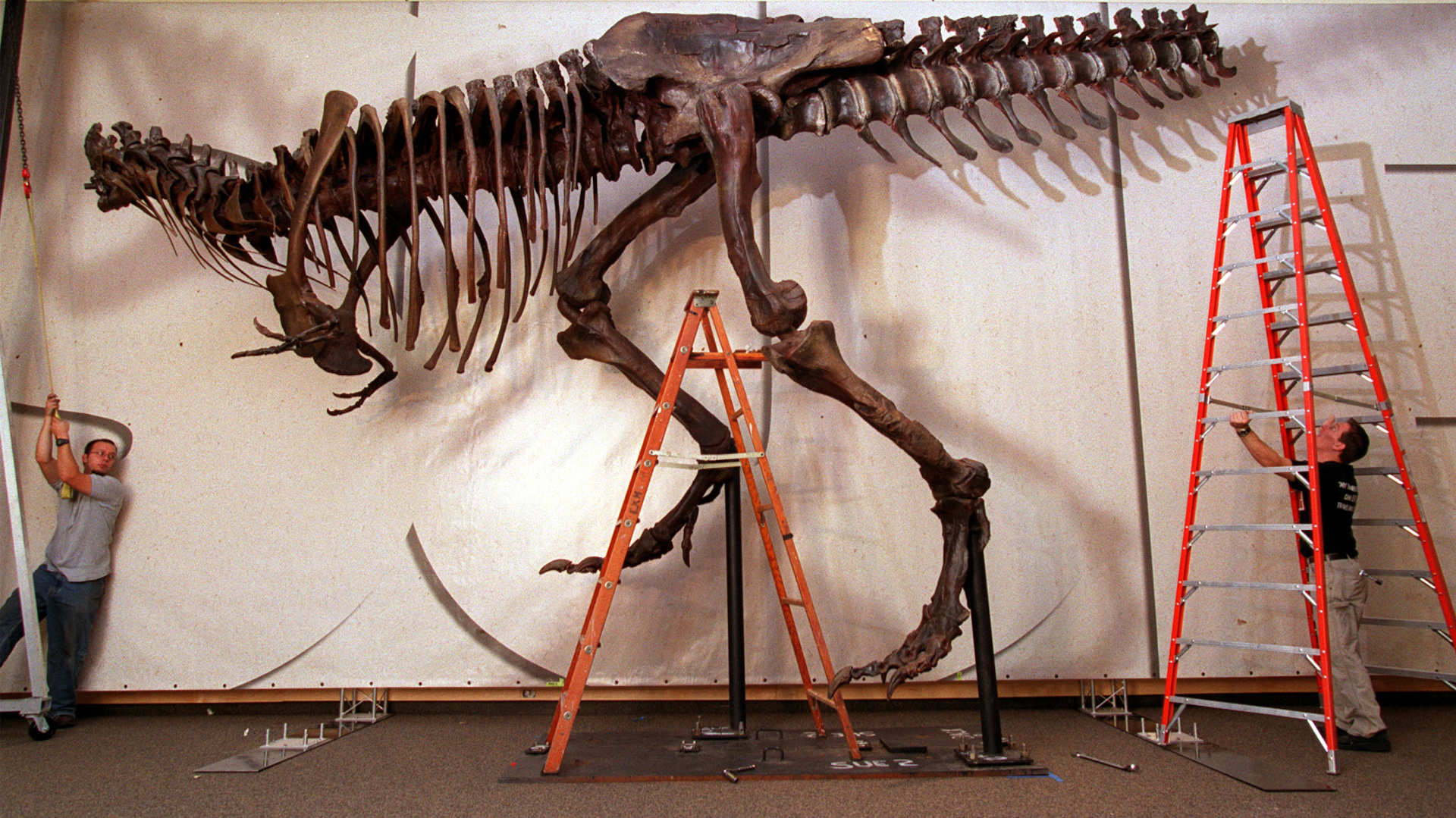

The funny thing about Tyrannosaurus rex is that it’s become so familiar — from Hollywood movies to comic books to children’s toys — that it’s easy to forget that we’ve only known of its existence for about 120 years. Certainly we were fascinated by fierce creatures long before, from lions and tigers to crocodiles and sharks — but, vicious as they may have been, they couldn’t muster the bite force of almost 13,000 pounds attributed to T. rex (imagine 13 grand pianos falling on you all at once). As author David K. Randall colorfully puts it, the impression one gets of the beast, when gazing at its remains in New York’s American Museum of Natural History, is that it “would clearly like nothing more than to crush your bones with its serrated teeth and eat you up in a gulp or two, like the monster from a child’s nightmare made real.”

In “The Monster’s Bones: The Discovery of T. Rex and How It Shook Our World,” Randall, a senior reporter at Reuters and the author of a string of popular nonfiction books, takes us back to the turn of the previous century, when hunting dinosaurs — or at least their bones — was the stuff not of nightmares but of dreams: dreams of fame and recognition for those who unearthed them; dreams of prestige for those who financed the expeditions; dreams of bustling exhibition halls and enthralled visitors for those who ran the museums where the skeletons ended up.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Monster’s Bones: The Discovery of T. Rex and How It Shook Our World” by David K. Randall (W.W. Norton; 288 pages)

Visual: W.W. Norton

At the heart of the story is man named Barnum Brown — his first name is an homage to circus showman P.T. Barnum — who grew up on a farm in Kansas, yearning to escape his humble origins. With backing from the American Museum of Natural History, Brown scoured the cliffs and canyons of the American West in search of long-extinct creatures. This, in Randall’s telling, is something Brown seems to have been born to do, having “a magical ability to unearth a specimen, like someone who can sit down and complete a jigsaw puzzle without first needing to find the edges.”

If a quarry had already been picked over by others, Brown was unfazed; he would climb down “and come out with fossils everyone else had missed, a feat that happened with enough frequency that it seemed like he could see layers beneath the surface.”

It was during an expedition to the Hell Creek Formation in eastern Montana in 1902 that Brown finally encountered the monster that gives the book its title. After using dynamite to blast a hole in the side of a hill, he found himself gazing at the remains of a creature “that no human being had ever laid eyes on.” Later that evening he wrote to his sponsor, Henry Fairfield Osborn, the then-curator of the museum’s vertebrate paleontology department, describing the discovery of “a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by Marsh.”

The Marsh in question was Othniel Charles Marsh, of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University; Marsh’s ongoing battle in the late 1800s with Edward Drinker Cope, who had been with the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, became known as the “Bone Wars,” with both men using all manner of deception and dirty tricks to one-up the other and establish themselves the master fossil-finder (and financially ruining themselves in the process). The “wars” finally ended with Cope’s death in 1897, but the allure of dinosaur bones continued — especially for the East Coast museums that understood the enormous public appeal of these long-dead animals.

As Randall tells it, dinosaurs were the perfect bridge between science and spectacle: Their bones dazzled young and old alike, but they also told a story about our planet and the living things that roamed its surface, millions of years ago. They also made it ever-harder to imagine that the biblical story of humankind’s origins ought to be taken literally — though there were still those who tried. A weekly London magazine, for example, suggested that the dinosaurs became extinct “because they were too large to go into the Ark, and so they were all drowned.” As Randall notes, the magazine did not ask why Noah “was not instructed to build something bigger from the get-go.”

The book occasionally reads like a turn-of-the-century version of “The Odd Couple,” featuring the intrepid, indefatigable Brown and the privileged socialite Osborn: two men who desperately needed each other, but who had little in common. But while Brown’s reputation appears to have reached the 21st century more or less intact, Osborn’s has not — as Randall shows us, he harbored noxious views on race, imagining a hierarchy with people like himself on top.

Osborn saw our planet’s history as a morality play, in which good triumphs over evil — and in which intelligence counts for more than brute strength (the extinction of the dinosaurs supposedly hammering home that last point). But Osborn’s theorizing did not end there. Randall writes: “The failure of a species with a body so powerful, and the triumph of humans with bodies so weak by comparison, seemed to Osborn evidence of a grand plan, a long pageant of life that peaked with present-day Anglo-Saxon humans in their rightful position of power.”

Osborn also failed to recognize the unity of humankind, believing instead in a kind of “parallel evolution” in which humans of differing skin colors evolved separately. Randall points out that, even in Osborn’s time, this was a fringe belief among fellow scientists; nonetheless he “never wavered in his refusal to accept that a common thread of humanity lay below the veneer of skin color.”

Moreover, as a senior figure who would later head the museum, his views held sway, with the various displays and exhibitions reflecting Osborn’s ideas about the supremacy of what he called the “Nordic race.” The Hall of the Age of Man, for example, guided visitors past depictions of ancient African and North American cultures, and “ending with Europe, suggesting a ladder in which light-skinned humans were the product of billions of years of refinement.”

Randall reminds us that the American Museum of Natural History hosted the Second International Eugenics Congress in 1921. (For some 80 years, a controversial statue of Theodore Roosevelt stood on the museum’s front steps. It depicted the 26th president on a horse, flanked by two shirtless men, one Native American and one of African descent, which the museum acknowledged communicated “a racial hierarchy that the museum and members of the public have long found disturbing.” The statue was finally removed this past January.)

Perhaps the message of the dinosaurs depends as much on the viewer as on the bones themselves. For Osborn, the bones were further proof of an imagined racial hierarchy. Others saw a cautionary tale more readily supported by the evidence: The bones of Tyrannosaurus and Stegosaurus and Diplodocus teach is that no creature lasts forever, not even the mightiest ones. “Physically, the beasts were monsters,” Randall writes; “symbolically they implied that humans, too, would one day be replaced.”

Many previous books have examined this episode in the history of science: A biography of Brown was published in 2010, for example, while “The Gilded Dinosaur” (2000) and “The Bonehunters’ Revenge” (1999) looked at the infamous Bone Wars — but even so, Randall has given us something fresh and engrossing. “The Monster’s Bones” takes us back 120 years, to the time when humans came face to face with a truly frightening beast, a relic from the Jurassic age that no one can gaze at unmoved. Today, T. rexes live (as it were) only in our museums, but the tale of how they got there, and why we expended so much money and effort to showcase them, reveals much about our own species.