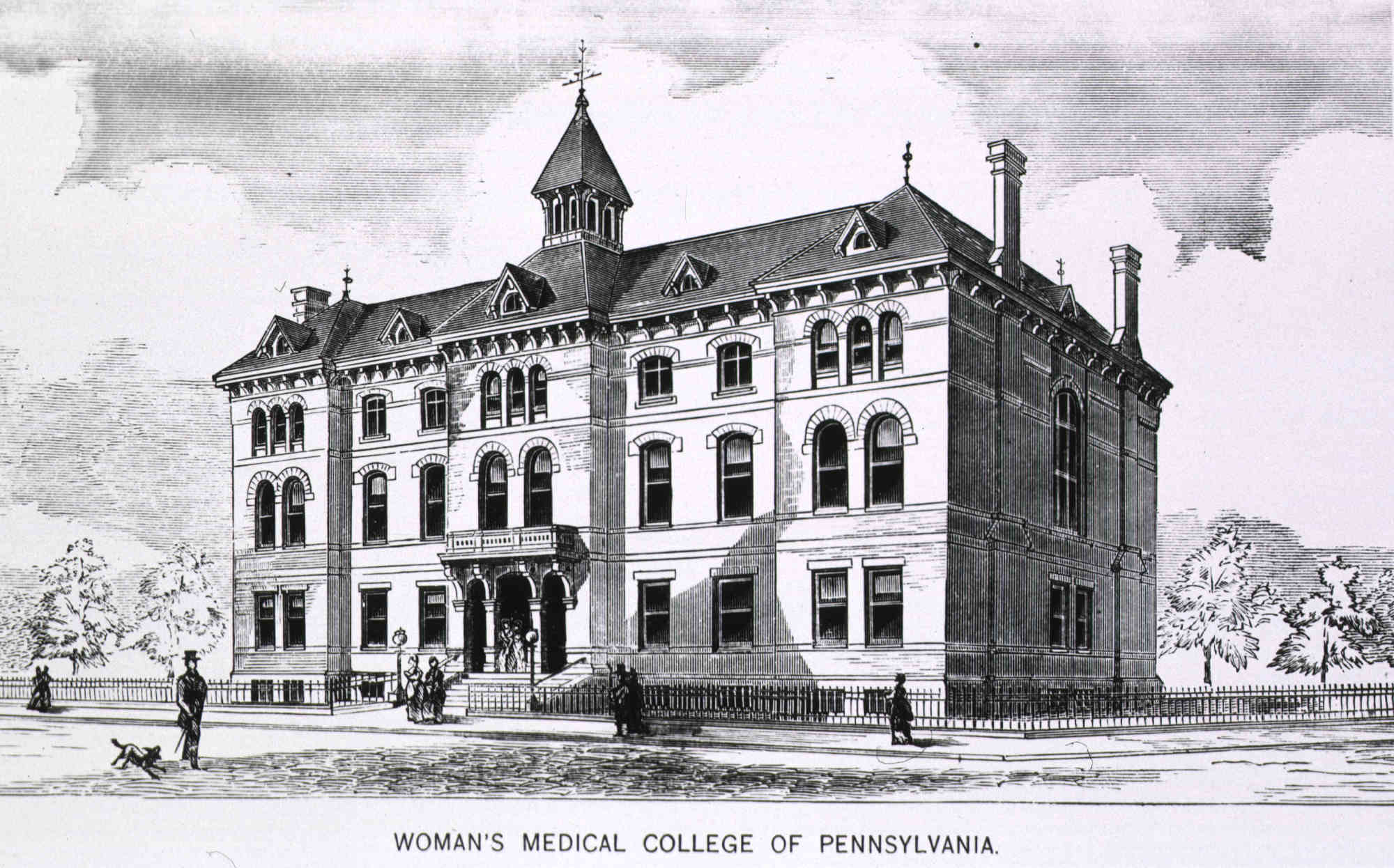

As she handed the clerk her entry ticket, Ann Preston was excited, if a little apprehensive. It was Saturday, Nov. 6, 1869, and Preston, dean of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, and her students, were about to attend a clinical medicine lecture at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia in a radical mixing of the sexes. Male medical students from Jefferson Medical College and the University of Pennsylvania had regularly attended these lectures for years; students from the women’s college were regularly refused admission. This was the second time Preston had brought students to a lecture there. After the first time, back in 1856, the women had been barred from returning. Until now.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, author Olivia Campbell, a journalist and author focusing on women, science, and history, shares a story that didn’t make it into her recent book “Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine.” (HarperCollins/Park Row Books).

Preston and her students were immediately reminded of their second-class citizen status when the clerk told them they would only be allowed to enter by way of the back stairs. Still, nothing could dim their enthusiasm. The determined dean and her 30 students began to file into the octagonal surgical amphitheater, gingerly squeezing their long puffy skirts through the tiered rows of seating that climbed the sides of the wall.

The day before the lecture, one female student had gotten hold of an ominous slip of paper that was being circulated among the male medical students. It read: “Go tomorrow to the hospital to see the She Doctors!” Clearly, the boys were planning some form of mayhem for this historic occasion. But what awaited the women students was worse than anything they could have imagined.

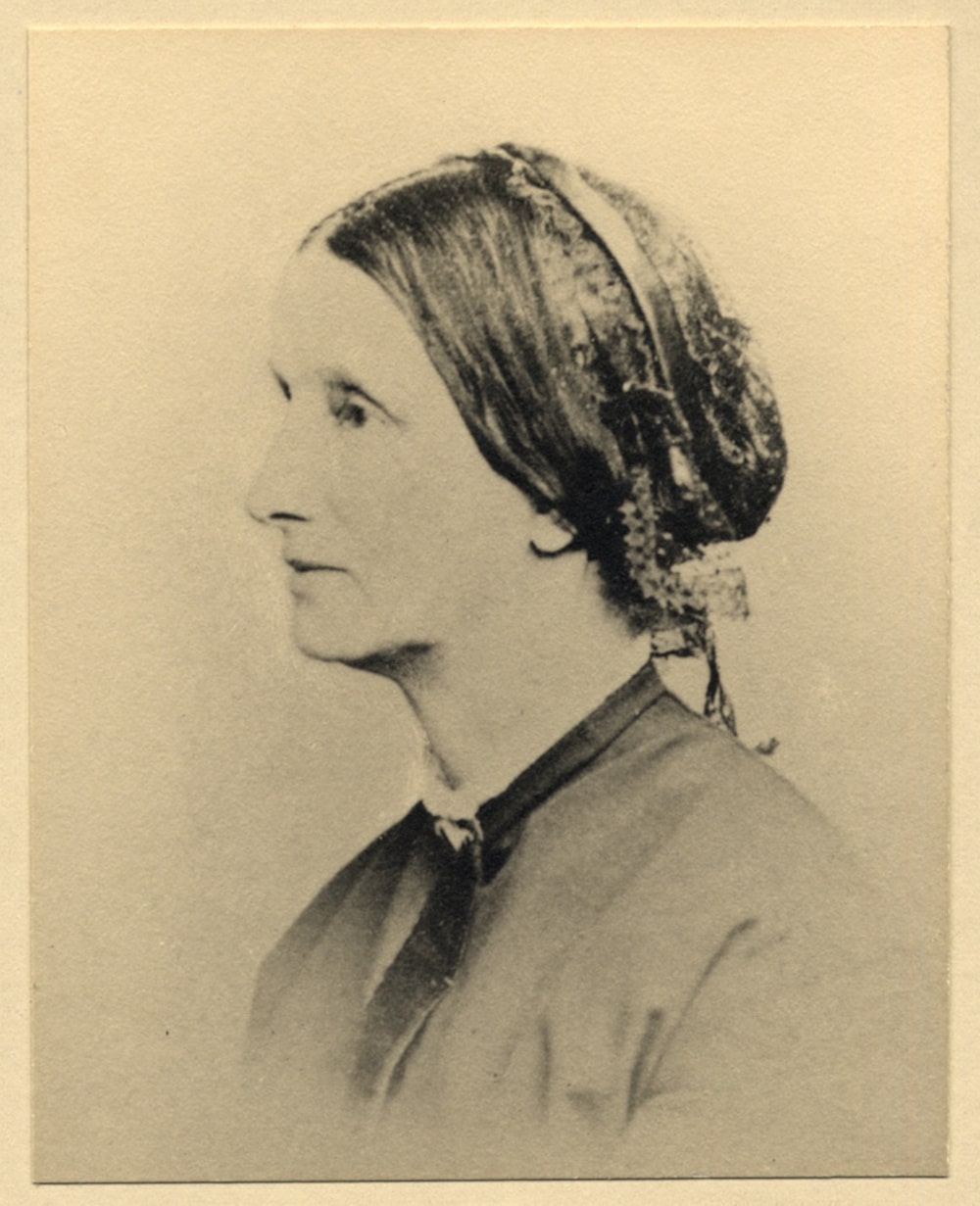

Preston, 55, was the first woman in America to become dean of a medical school. Nineteen years prior, she was one of the college’s very first students, back when it was called the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. After a mere three years of schooling, she became its professor of physiology and hygiene. She was so petite that she often stood on a block while teaching. Preston had eight siblings, but neither of her two sisters survived to adulthood and her mother was prone to frequent bouts of illness. She decided women could improve their health if they knew more about their own physiology, so she studied the subject and started teaching classes to girls and women in her community of West Grove, Pennsylvania.

As a professor and administrator, Preston fervently advocated for her students to have the same educational opportunities as men, knowing they were lacking, in particular, clinical training. Back in 1855, she began petitioning local hospital managers to allow her students admission to clinical lectures. The following year, the hospital finally agreed to allow Preston and a few students to attend a lecture. That would be the first test of whether male and female students could learn together peacefully at Pennsylvania Hospital. The institution was the nation’s first public hospital, established in 1751 by Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond, and housed the nation’s first surgical amphitheater and medical library.

The test did not end well. Not everyone was elated about the prospect of women in the classroom. Professor David Hayes Agnew was livid that women were being permitted to invade the male sanctuary of his lecture hall. Hoping to scare them off, Agnew planned a case demonstration requiring a male patient to fully disrobe. When that didn’t work, he successfully appealed to the hospital board to deny women any further admittance. That blow was soon followed by another: in 1858, the Philadelphia County Medical Society formally ostracized the women’s college, preventing them from attending public teaching clinics or gaining membership in any medical society.

Preston remained unfazed. After another 13 years of persistence the hospital finally gave in again. Now, Ann and her students would test the waters a second time with a new crop of students. And the male students did their best to trouble that water.

Knowing that women were going to be in attendance, in the days leading up to the lecture the male students passed around the note warning about the impending “She-Doctors” in order to ensure the men made a forceful, territorial showing. They hoped their behavior and number would show the hospital managers how much they disapproved of their space being tainted by women. The men were also hoping to make a statement about how women were not suited to the medical profession in general.

“When we turned up at the clinic, pandemonium broke loose,” student Anna Broomall recalled. Awaiting them in the upper tiers of the amphitheater were nearly 300 male medical students — far more than were typically in attendance. The men began hurling epithets, catcalls, and other offensive language at the women. Some men insulted the women’s appearance while others spit tobacco juice on their dresses.

Elizabeth Keller, another student, said they entered the hall “amidst jeers and groanings, whistling and stamping of feet, by the men students, who had determined to make it so unpleasant for us that, from choice, we would not care to attend another.”

The clinical lecture would be delivered not by Agnew, but by two other doctors, William Hunt and Jacob Da Costa. During the first hour, mild medical cases were slated for presentation by Da Costa: victims of malaria, sunstroke, and dropsy (swelling of the soft tissue) would be paraded in front of the large student audience to be prodded, examined, and discussed. In the second hour, Hunt’s surgical procedures would take center stage. But no teaching could commence until the ruckus was squelched.

At the height of the uproar, hospital manager William Biddle came bursting into the amphitheater to try to calm things down. “Hat! Hat!” the male students yelled at Biddle’s dark, wide-brimmed orthodox Quaker hat. As a wealthy man of high public standing, this was likely one of the worst insults he’d ever experienced. The students either didn’t know or didn’t care that Quakers believed in keeping their head covered.

He told the men that the women were there with the hospital managers’ blessing and should not be subject to such insults. Biddle said any man who was found to be insulting the women would have his lecture ticket, which cost $2, withdrawn. His request for them to behave provoked even more outbursts. The men began to hiss loudly at Biddle’s rebuke.

“Oh, I don’t care for your hisses,” Biddle snapped back calmly.

The jeering continued, prompting a second hospital manager to rush in and command: “Boys, we will not have this.” Biddle entreated the students to remember their character as gentlemen, and declared that their continued poor behavior had forced him to stay and watch the rest of the lecture to monitor them.

Ann Preston was the first woman in America to become dean of a medical school. She believed women could improve their health if they knew more about their own physiology, so she studied the subject and started teaching classes to girls and women in her community

Visual: "Ann Preston," Photo ID p0119 / Legacy Center Archives, Drexel University College of Medicine

Amid the swelling cacophony, in swept the surgery professor, Dr. Hunt, along with some assistants carrying a stretcher bearing his first patient. He bowed to the men only and addressed a greeting to the “gentlemen,” prompting the hissing to intensify yet again.

“What can you see today?” Dr. Hunt asked the patient as he sat up. This man’s eyesight had been harmed in a mining accident. Hoping to make an example of the women, he pointed toward the section of the audience where they were seated, and asked, “What do you see now?”

“Patrick,” the patient replied flatly, referring to the medical assistant standing nearby.

“Look up! Look higher, and tell me what you see,” Hunt prodded dramatically, unsatisfied with the result of his little exercise. The man strained and squinted.

“Light! I see light!” he proclaimed.

Later, a Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reporter decided this comment carried a much deeper, more poetic meaning: “Was there a signification in that blind man’s words? Was not light dawning upon bigotry and oppression when women were even thus allowed to avail themselves of an opportunity for acquiring knowledge that they would dispense for the alleviation of suffering?”

Another surgical patient presented at the lecture was a man with a fractured femur that was not healing well. The attendants brought the man in, placed him recumbent on a “revolving couch,” and pulled off his boots. The male students stamped and growled. The doctor provided the patient with a blanket to cover his private area, but at some point while the doctor measured the patient’s leg, his groin was briefly exposed.

This quick flash served yet another “signal for an explosion among the students,” a news report noted, provoking “mock applause, clapping, stamping, and shouts of laughter, mingled with hisses and jeers, in one wild uproar.”

During the last hour of the lecture, the male students rained down a barrage of tinfoil wads, paper missiles, spitballs, and tobacco wads upon the women. Throughout it all, the female students never flinched or retaliated, choosing instead to quietly listen and attempt to learn whatever they could amid such chaos. The women’s lack of reaction must have further incensed the men, for they surely hoped to show how fragile and emotional women were.

Though medical students were often characterized as a rather wild, roguish bunch, this type of behavior was not typically how men were expected to treat women of a similar class in public. “For any man with even a pretense of breeding to jeer, mock, perhaps even stone and spit upon women could hardly be imagined in mid-19th-century America,” according to medical historian Steven J. Peitzman.

One student, Sarah Hibbard, said she tried to remain unflappable for two hours “amid the groans and hisses of as ungentlemanly a set of fellows as one would care to meet, after paying just as much for our tickets of admission as they.” By the end of the clinic, Broomall said she too “had scarcely heard a word of what our preceptors had been trying to tell us.”

The harassment didn’t end there. “We were hustled and jostled into the hall,” Broomall remembered. When one of the hospital managers went to close the gates, the boys “burst the barriers open and knocked him over in the fracas. He raised his trembling hands in protest, saying ‘The Pennsylvania Hospital will not have this!’”

The men lined up along both sides of the pathway leading through the yard from the hospital so the women would have to run their gauntlet of intimidation as they left. But upon seeing the mob, the ladies took a different route.

“To get out, [we] had to take the road and walk to the street to the tune of ‘The Rogues March,’” Hall recalled. The tune is a taunt typically played when punishing or discharging military men. “Our students separated as soon as possible. All who could took the little antiquated horse cars in any direction they were going. The men separated also, and in groups of twos, threes, and fours, followed the women.”

“Borne along as on the crest of a wave we found ourselves in 8th street and went 20 different ways, still pursued by taunts and jeers,” Broomall said. One newspaper reported that the male students “followed them some distance, greatly to their annoyance, uttering various uncouth noises and indecent comments, and making other manifestations peculiar to this class of ‘gentleman.’”

Keller claimed that “on leaving the hospital we were actually stoned by these so-called gentlemen.”

Hibbard exasperatedly pointed to the deeper reason why most women sought to become physicians in the first place: “And yet we bore all this for what? Simply that we might be better fitted to minister at the bedside of our mothers, sisters, and friends throughout the land.”

The Philadelphia “Jeering Episode,” as it came to be known, went far from unnoticed. The press was all over it: “Blackguardism,” proclaimed The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, “Disgraceful,” “Female Students Assaulted by Their Male Brethren” read The York Free Democrat headlines. One Philadelphia reporter mused cheekily: “Why these sagacious youths object to female physicians we do not know, unless it is that they are conscious of intellectual deficiency, and are afraid of competition from persons whom they feel to be their superiors mentally as they are morally.”

One young man purporting to have been present at the event sent a letter to the editor of a local New Jersey newspaper attacking the very idea of women in medicine. His views reflected that of many medical men: “Who is this shameless herd of sexless beings who dishonor the garb of ladies?” the man insisted. “This neuter 34 who have shamed common decency by their unwelcome and uninvited presence to the disgust of every student and the loathing of the instructors! Who, by their immodest persistence have shamed all gentlemen from those clinics!”

News of the riot spread far beyond the local papers, and opinions abounded. The New York Citizen and Round Table was bewildered by these “Wild Women determined to witness the carving and cutting of the masculine form divine.” The New York World almost sounded impressed that such a riot would occur in “Philadelphia, the dullest village in America.”

Even The Scotsman covered the event, poking fun at the medical establishment’s pearl-clutching response to the idea of women doctors: “We know not which most to admire — the cool assumption that the medical profession exists only to fill the pockets of its members, or the serene assurance that no woman has a right to expect to be allowed the chance of earning a living till all male competitors are safely and sufficiently provided for!”

As for Dr. Agnew, he simply couldn’t bear the idea of teaching women. It was so unbearable, in fact, that when the board of contributors proclaimed that regardless of the riot, women would continue to be admitted to clinical lectures, he quit his job, despite being poised to become chairman of surgery at the medical school.

Ultimately, the episode failed to scare women away from attending clinical lectures. Actually, it did the opposite. By beginning to turn the tide of public opinion in favor of the women, who were now largely seen as undeserving victims of ungentlemanly brutes and simply seeking to obtain an equal education, the riot gave the women’s movement considerable momentum.

“The conduct of the male students needs no comments further than to say that their ‘loss was our gain,’ for certainly they did lose and certainly we did gain,” Hibbard declared in her diary a few years after the incident. “If these poor fellows had sought to do us a life-long favor, they could not have done it more effectively than they did in their conduct towards us during those sessions.”

Broomall, despite this harrowing experience, went on to transform women’s health in Philadelphia. After graduating from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (as the school’s name was spelled at the time), she studied obstetrics in Paris and Vienna, then returned to accept the chief resident position at her alma mater’s women’s hospital. Before long, she was chair of obstetrics. She was one of the first doctors in the nation to institute regular prenatal and postnatal care, and she also ensured that her nurses kept up with the latest medical advances coming out of Europe. These practices, in addition to her emphasis on the use of antiseptics and cesarean sections when medically necessary, ushered in an incredibly low maternal mortality rate.

“The present generation should know what such women have done for all other women,” Broomall once proclaimed of her fellow medical trailblazers. “More than one among us hold in her capable hands the lamp of Florence Nightingale, and the flame of it burns bright and clear.”

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author focusing on women, science, and history. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Atlantic, New York Magazine, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Aeon, Scientific American, Smithsonian Magazine, and Literary Hub. Her first book, “Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine,” was published in March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Most quotations come from archival documents held at the Drexel University College of Medicine’s Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I remember reading on admission for female students to Dental schools in a similar line if not worser in 1800s.