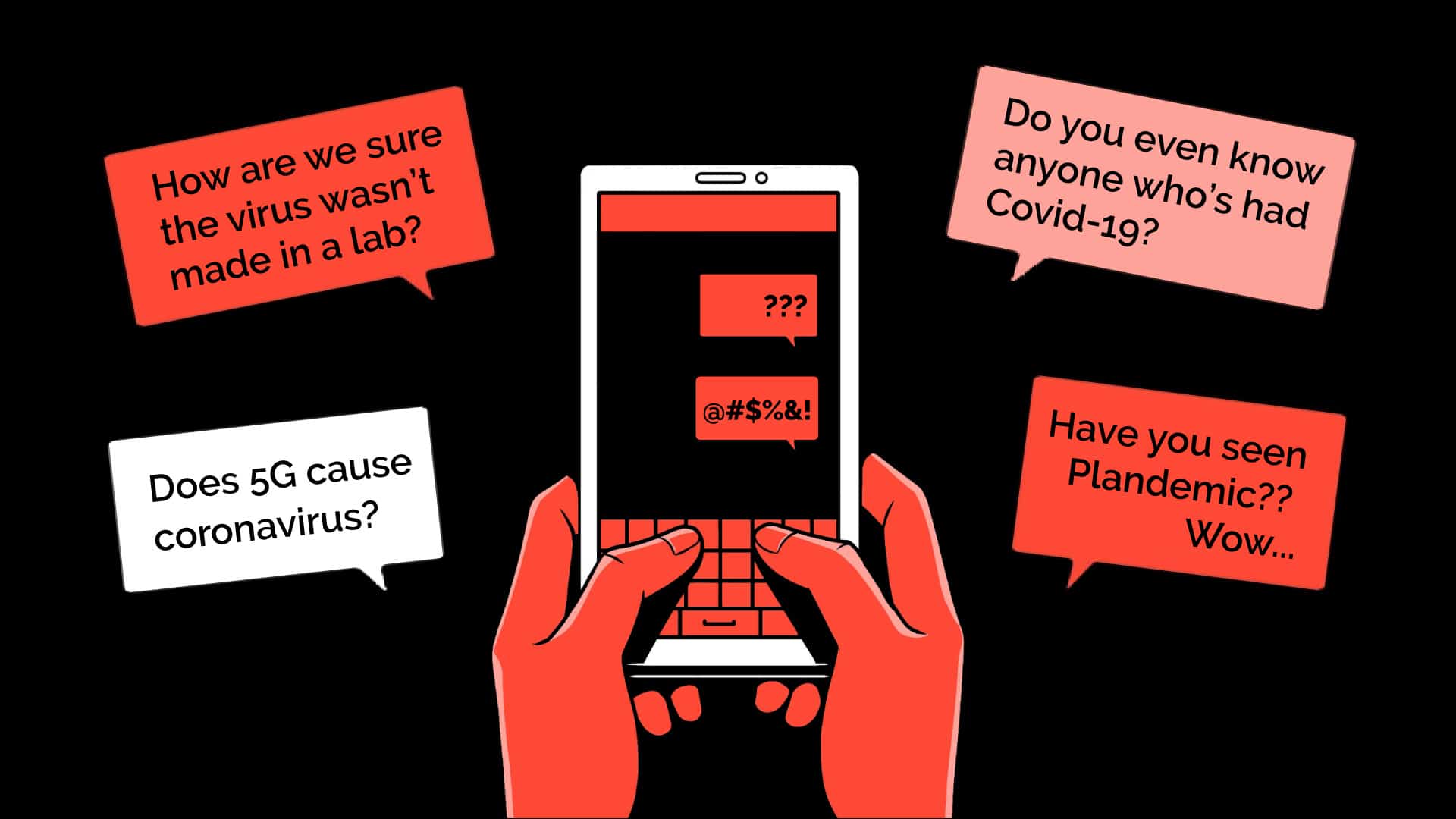

A few weeks ago, I took an uncomfortable trip down the rabbit hole of Covid-19 conspiracy theory videos. As a newly minted M.D. who will soon be taking care of patients at a safety-net hospital on the frontlines of an ongoing pandemic, I was especially pained by what I saw. There was the infamous “Plandemic” video, which asserts that a cabal of elite individuals and organizations is using Covid-19 to cement power. There were also false claims that the new coronavirus was created with the backing of Bill Gates, for the purposes of diminishing our freedoms.

Watching the videos pushed me to think about why so many viewers gravitate toward them — and how best to counter their misinformation. On both of those fronts, my experiences working with patients have taught me valuable lessons.

I’ve learned that conspiracy theorists are often neither malevolent nor unintelligent. Rather, many are afraid of their own powerlessness, and these theories offer them a semblance of control. Believing that Covid-19 was perpetuated by organizations with evil intentions allows conspiracy theorists to affix their anxiety onto a big, bad villain, rather than acknowledge our collective powerlessness against the whims of nature. It helps allay existential fears regarding the indifferent, arbitrary universe we live in. I recognize these emotions because I have seen them time and time again in my patients who are hesitant to heed medical advice, either due to misinformation or due to a reluctance to change their habits.

A second allure of conspiracy theories may be that they allow the believer to lay claim to a secret truth that is not limited by one’s level of wealth or education. Previous studies have demonstrated that lower education levels correspond with increased reliance on conspiratorial explanations, with one concluding that “education may undermine the reasoning processes and assumptions that are reflected in conspiracy belief.” The average Covid-19 conspiracy theorist has probably never received the training needed to interpret complex academic papers. I couldn’t send them one of the dozens of research articles I’ve read over the past months and expect them to grasp its nuances. Yet, if I were to challenge them on their beliefs, it wouldn’t be surprising if they accused me of being the one who hadn’t done my due diligence in researching Covid-19. Conspiracy theories abound because they are easy to understand and fit neatly within their own twisted internal logic. The truth is often hopelessly complicated, but the best lies are simple and easy to believe.

Fortunately, physicians have a powerful tool to persuade patients on a wide range of issues, from smoking to vaccines: motivational interviewing, a form of conversation therapy used to assess and guide patients in the process of making positive changes. As a part of motivational interviewing, I ask my patients about their biggest barriers to changing their minds or habits; this way, I know which worries or misinformation to try to address. I never resort to guilt-tripping, fearmongering, or ridicule, because those who feel their beliefs are being threatened become even more entrenched in their views.

At the end of every discussion, I reassess my patients’ willingness to change. Most of my patients aren’t willing to give up their deep-rooted beliefs or habits after a single office visit, so I remain open to an ongoing conversation. Over the course of many visits, my patients get to know me and understand that I want the best for them. By fostering a sense of mutual respect, I can often nudge them toward healthy behaviors, like taking their medications or taking actionable steps to quit smoking.

So, now, when I encounter a Covid-19 conspiracy theorist, I approach the conversation like this: I empathize with them, acknowledging that Covid-19 is horrifying and that we all want our loved ones to be safe. I tell them that I don’t trust the conclusions of some of the conspiracy videos on the internet, and I offer to refer them to more trustworthy sources of information. Even if they don’t change their mind, they know that I take their concerns seriously. The conversation about Covid-19 will be an ongoing one, but in time, I hope that evidence-based views will win the conspiracy theorists over.

Viral misinformation has proliferated during the pandemic, and many of our friends and families have been afflicted. Fortunately, there is a potential cure: healthy doses of active listening, empathy, patience, and respect.

Yoo Jung Kim (@yoojkim), M.D., is a recent graduate of the Stanford University School of Medicine and is currently working at a safety-net hospital in San Jose, California. Her pieces on science and society have been published in The Washington Post, U.S. News and World Report, the San Francisco Chronicle, The Seattle Times, The San Jose Mercury, and The Korea Times.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

“I offer to refer them to more trustworthy sources of information.” – What is that trustworthy information? How do you know it is trustworthy? Just because we spent millions of dollars for our education, does not prove that what we have learnt is trustworthy. Here is an example.

It has been found that placebo cures all diseases. Can any doctor explain why and how it cures? Can any doctor prove that medicine effect is not the same as placebo effect?

I am sure you cannot. Then why medical science and in fact all of science is not a conspiracy? Take a look at https://www.academia.edu/43619619/Truth_and_MLE_-the_only_way_for_Eternal_Global_Peace_on_Earth for more details.

“Believing that Covid-19 was perpetuated by organizations with evil intentions allows conspiracy theorists to affix their anxiety onto a big, bad villain, rather than acknowledge our collective powerlessness against the whims of nature.” Is the appearance of the virus really a ‘whim of nature’? Or more a reaction to our lack of respect towards nature? Factory farming on a huge scale is contributing to viral recombinations and possibly for more viruses to jump from animals over to humans. Deforestation means we are encroaching animal territory and loss of biodiversity will reduce and eliminate natural predators. In my view this is manmade but not by villains but by each one of us who buys cheap food from supermarkets, for example.

Great article! Too bad the conspiracy theorists I know personally believe that any reliable or factual sources (cdc, nih, who etc) are part of the conspiracy theory to keep “us” under control.

“Viral misinformation has proliferated during the pandemic, and many of our friends and families have been afflicted. Fortunately, there is a potential cure: healthy doses of active listening, empathy, patience, and respect.”

Kudos to the author, and may we all learn from this. Reckon I’d better learn motivational interviewing.

I came across this article in the Medscape app.

Thank you for a more open look at conspiracy theorists. Maybe I will learn better how to deal with them. My husband is a conspiracy theorist, and he is intelligent. Unfortunately, he wants me to be one too, and to believe what he believes. He says I’m a liberal sheep. I am not liberal, and see him as the sheep.

I try to not to react because my eardrums are calloused from hearing his loud opinions regularly. I try to let him vent. I really hate noise, but peace makes me “guilty of complacency.”

Also: Many conspiracies have proven true. This is one reason that a person who collects intel will tell you there’s no such thing as a coincidence. Additionally, as retired Special Forces, my husband’s job was to find vulnerabilities that could be exploited by conspirators.

I would love to see a list of the conspiracies that proved true!

Well in ethics and excellence in advocate writing.

I interfaced years ago as a heavy military backup unit to extract citizens in worst virus similar to what has tanked california. California sits at a lesser extent in symptoms but shows defined symptoms of short term memory as well as blackouts.

Motivational intervuewing works well espcialky w a doctor.People will b more willing to listen to t trusted doctor.There arw kess varriers.

it is dangerous to label and dismiss those who ask questions. good science and good medicine are impossible without retaining an open mind. you do not need to share a belief to respect it in others. like the existence of God, no-one can prove it one way or another and neither can you categorically disprove what you decide are conspiracy theories.

Agree

I agree that it is dangerous to label those who ask questions. At the same time most conspiracy theorists I have encountered don’t ask questions. They are absolutely unquestioning about their theories and become extremely defensive if you question them about their beliefs. Ever engage in conversation with a chemtrail believer or a flat earther? If you have you will know what I mean. They don’t question, they tell.