A coronavirus is a sphere, five millionths of an inch across. Proteins project from its surface like spikes, making the tiny virus look, in the eyes of some researchers, like the corona of the sun. Since it infected a human being in a market in Wuhan, China, on or around December 1st of last year, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and the resulting disease, Covid-19, has infected at least 98,000, with some tallies topping 100,000 as of Friday morning. At least 3,300 people have died. It appears to be deadlier than the flu, but slightly less contagious. Even as cases slow down in China, outbreaks have spread in South Korea, Iran, Italy, France, Germany, and, increasingly, the United States.

There were fatalities this week in Washington state and California. A cruise ship has been anchored in San Francisco Bay as officials evacuate sick passengers and prepare to test thousands more, who wait confined on the boat. Fresh cases in the New York City suburbs suggest that the coronavirus may be spreading quietly in the country’s largest urban area, which now has at least 2,700 people parked at home under voluntary quarantine. Someone tested positive in North Carolina; someone else in Tennessee.

The most straightforward observation — one perhaps articulated too rarely in a media and political climate that rewards sureness — is that no one knows for certain what will happen next, nor how much harm it will cause.

Indeed, the news this week was, in some respects, a study in how our society reacts to a state of profound uncertainty. U.S. President Donald J. Trump made sweeping, confident, and sometimes baffling pronouncements. Global stock markets climbed, plunged, wavered, then plunged again, amid fears of economic shutdowns and major losses in the airline industry. The Federal Reserve cut interest rates. Congress approved an $8.3 billion emergency spending bill, with near-unanimous votes in both chambers. Hand sanitizer sold out in grocery stores. And researchers continued to analyze — and learn from — the ever-larger trove of data about the way the virus infects, mutates, and spreads.

For its part, the United States has invested billions each year in the scientists and workers of its public health systems, which are likely among the best prepared in the world for a pandemic. At the same time, recommendations after previous outbreaks, some analysts say, have been largely ignored. And gaping health coverage gaps have raised concerns that many Americans, fearful of high co-pays or steep penalties for missing work, will avoid getting care or going into self-quarantine, making the virus more difficult to contain.

In this week’s Abstracts, we offer readers a roundup on several key aspects of this fast-changing story — as well as some recommendations on who and what to read in the weeks ahead.

• It’s still not clear how deadly the virus is.

A new analysis by the World Health Organization this week found that SARS-CoV-2, the newly emerged coronavirus, has a case fatality rate (CFR) of 3.4 percent, a number unnervingly higher than seasonal flu (0.1 percent). Still, researchers acknowledge that the precise lethality of a fast moving and evolving virus is itself an ever-moving target, and that numbers are uncertain at this point. Some have found in that uncertainty cause for relief. “Covid-19 isn’t as deadly as we think,” was the headline on a story by Slate’s medical columnist, Jeremy Faust, a Boston-based MD, which predicted that the CFR numbers are likely to drop, perhaps even by a couple percentage points, as more information comes in. That fatality rate is one of the most important questions in understanding an outbreak, The New York Times noted, “and one of the least understood.” But experts contacted by the paper did not dismiss the higher numbers out of hand, instead noting that concerns remain real and that most viral researchers expect the final numbers to portray an infection that is, indeed, more deadly than seasonal influenza.

• Assisted living facilities seem especially vulnerable.

A nursing home in a suburb of Seattle became the site of a coronavirus outbreak last weekend, raising concerns about the vulnerability of the 2.5 million Americans who reside in assisted living or other similar facilities. With the city of Kirkland, Washington already the site of the country’s first coronavirus death on Saturday, a man from the Life Care Center nursing home was reported dead on Sunday. By Thursday, the death toll had climbed to seven. The infection caused by the coronavirus, known as Covid-19, is particularly lethal in older populations: Data from China, where the virus first began circulating, show it kills nearly 15 percent of patients aged 80 and older. Nursing home conditions could increase the risk, as residents are transferred to and from hospitals. Family members of those in care say protocols often aren’t followed and staff are chronically overworked. Following the outbreak news, the Centers for Medicaid Services said it will focus all nursing home inspection resources on infection control. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is instructing all facilities to post signs to discourage people with respiratory illness from visiting and to provide employees with sick leave.

• The outbreak, and responses to it, have fueled racist incidents.

Individuals of East Asian descent faced physical attacks, online harassment, and discriminatory treatment in several countries this week as SARS-CoV-2’s identification in Wuhan, China continued to prompt racists and xenophobes to act on their beliefs. On Monday, a 29-year-old interpreter living in The Hague, Netherlands, said two men yelled “Chinese” and tried to punch her off of her bicycle. The same day, a 23-year-old student in London posted on Facebook that he had been assaulted by a group of people, one of whom he said yelled: “I don’t want your coronavirus in my country.” London police subsequently released photos of four men they’re seeking in connection with the attack. In Italy, the U.K., and the U.S., people reported racist comments at work, school, on public transportation, at the police station, and, of course, on social media. News outlets drew criticism for running inaccurate stock photos of Asian people and neighborhoods alongside coverage of new cases. While this troubling trend comes as little surprise to disease historians and public health experts, it puts millions of citizens in danger — physically, mentally, and emotionally — and robs them of their basic rights. Further, stereotypes about who is likely to carry or transmit the virus often run contrary to the science, and experts say this may ultimately make it harder to contain the outbreaks.

• Critics keep asking: Can the Trump Administration handle it?

President Trump’s Wednesday evening interview with Fox News — in which he called WHO’s latest coronavirus death-rate estimate “a false number” and suggested that coronavirus victims could get better by “sitting around and even going to work” — has critics questioning his ability to respond to the outbreak. Of concern is the president’s penchant for downplaying the virus’s threat while overstating progress on its treatment, often in contradiction to his own administration’s health experts. The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake was particularly baffled by Trump’s performance at a Monday meeting of government coronavirus task force and pharmaceutical executives, during which the president repeatedly, and falsely, suggested that a vaccine could be available to the public in less than a year. He “didn’t seem to process the fact that producing a vaccine means conducting months and months of trials,” Blake wrote. At Mother Jones, Will Peischel and Jessica Washington fault the Trump administration for a long list of blunders, from the disbanding of the National Security Council’s pandemic response team to the slow roll out of virus testing kits. But at the top of their list of Trump’s faux pas? Naming Vice President Mike Pence — the former Indiana governor with a maligned track record on outbreaks — to lead the coronavirus response.

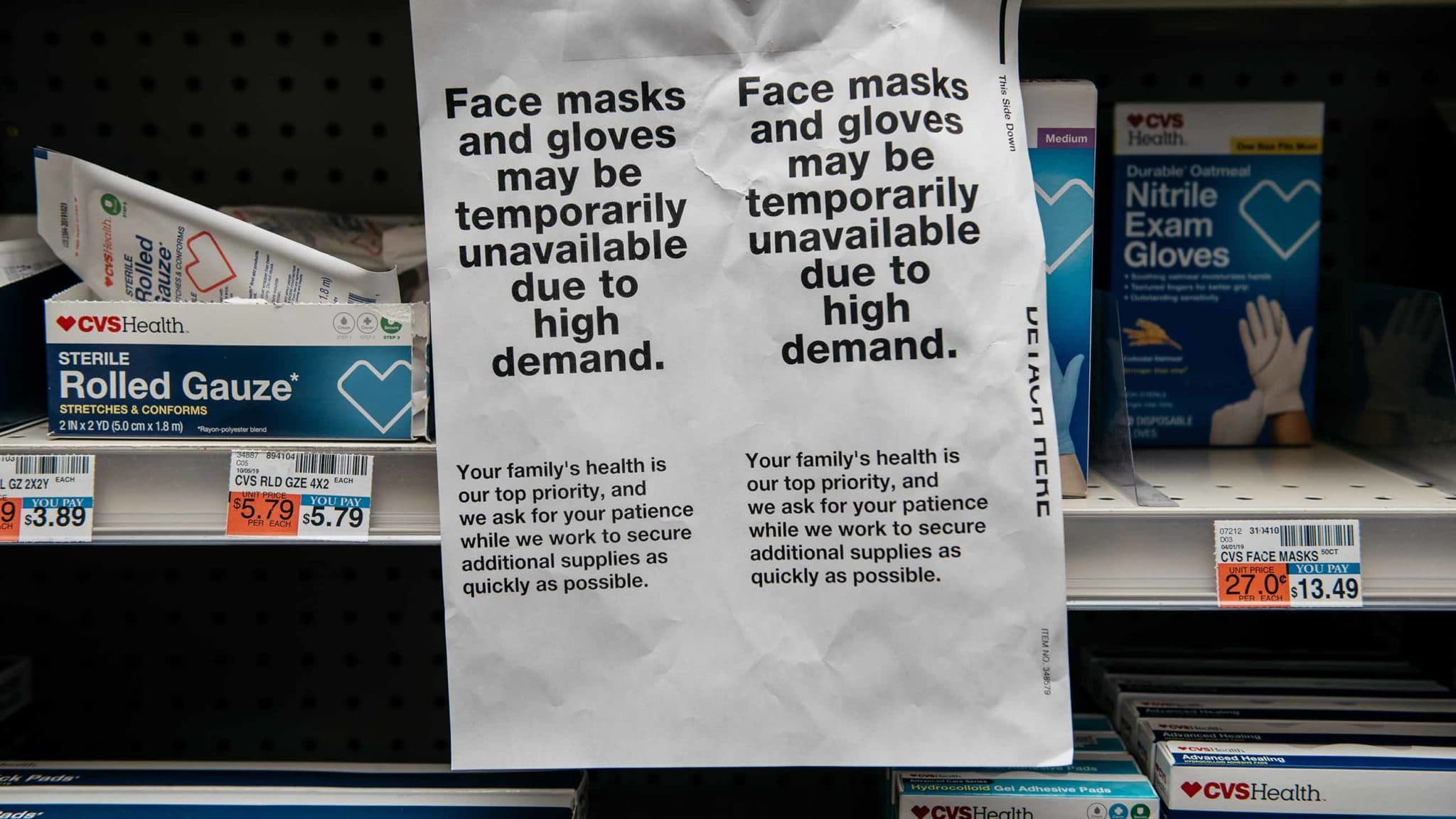

• Virus fears continue to spark price-gouging, equipment shortages, and even some opportunistic marketing.

With nervous consumers and even health care workers flocking to online retailers to purchase face masks, hand sanitizer, and hazmat suits ahead of the fast-spreading virus, some sellers at Amazon and other shopping platforms began jacking up prices in an effort to cash in on the deluge. CNBC noted on Wednesday, for example, that at Amazon, N95 respirators, which are capable of filtering out viruses, had seen asking prices rise from about $13 to as much as $195 before supplies were exhausted. Eight-ounce bottles of hand sanitizer were priced above $50 — sometimes even above $100 — on Amazon and eBay. The profiteering met with official warnings from California’s governor, and on Wendesday morning, Senator Edward Markey, a Massachusetts Democrat, wrote a letter to Amazon’s chief executive, Jeff Bezos, demanding information on what Amazon was doing to curtail price-gouging on its platform. The rush of buying has led to cascading reports of shortages across the country — and across the globe, while elsewhere online, entrepreneurial hucksters have been busy churning out self-published coronavirus-themed books, often rife with spelling errors and grammatical mistakes, in an effort to capitalize on public fear. In at least one instance, a title falsely attributed to the U.S. Department of Health and Human services was removed from Amazon, but the titles appear to proliferating faster than retailers can monitor, and the same book — co-authored by the non-existent “U.S. Department of Health” — was still being peddled at Barnes and Noble on Friday morning. Experts urged consumers to deploy a healthy skepticism when purchasing Covid-19 themed books.

• Reliable information is out there.

There are plenty of reliable information sources on the emerging pandemic. Below, a list of some of the journalists, experts, and publications that Undark is following.

- Helen Branswell (@HelenBranswell), senior writer, infectious diseases, STAT

- Peter Sandman and Jody Lanard, risk communication experts

- Kai Kupferschmidt (@kakape), molecular biologist and science journalist, Science Magazine

- Trevor Bedford (@trvrb), computational biologist, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle

- Lawrence Gostin (@lawrencegostin), professor of global health law, Georgetown University

- Wendy Mariner (@wendymariner), health law professor, Boston University

- Julia Belluz (@juliaoftoronto), health correspondent, Vox

- Kaiser Health News, full coronavirus coverage

- ProPublica, full coronavirus coverage

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, latest coronavirus news

- World Health Organization, rolling coronavirus updates

- Global Covid-19 Case Tracker, Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering

Undark will continue to provide weekly roundups of coronavirus and Covid-19 news each Friday for as long as the pandemic continues.

Deborah Blum, Jane Roberts, Ashley Smart, Frankie Schembri, and Tom Zeller Jr. contributed to this roundup.