Novels thrive in times of upheaval. Think of Don Quixote tilting at the death of magical thinking in the Middle Ages, Defoe’s Colonel Jack navigating the new social mobility of 18th-century England, or George Eliot marking the transformations of the early Industrial Revolution.

These are mirrors of the new present day, user’s manuals for new worlds: Here are love, duty, mortal commitment, laughter, and loss, in a new key, on a strange new landscape. Here is what and how it is to be human. Take my hand, the author says, and bid the receding shoreline goodbye.

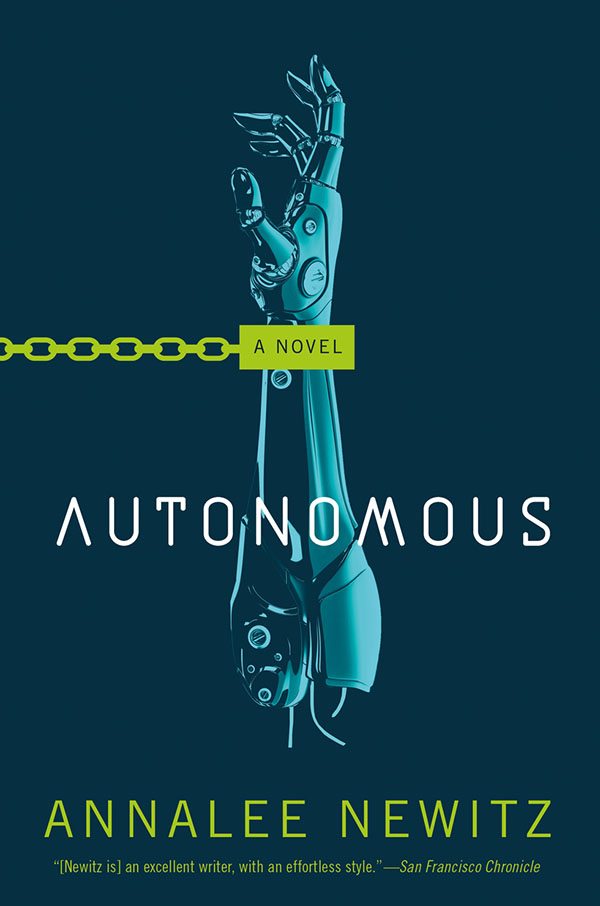

BOOK REVIEW — “Autonomous,” by Annalee Newitz (Tor, 304 pages).

The explosive upheavals of our globalized, tech-heavy world should be prime material, provided a novelist learns enough about our powerful and abstruse domains. It’s not critical to master synthetic biology, applied quantum physics, industrial artificial intelligence, or the really weird, cutting-edge stuff. Basic understanding is plenty, along with the emotional truth of the new system of knowledge. No matter how far it’s set in the future, even science fiction is still a portrait of the present.

On that count, Annalee Newitz is estimably qualified to write a user’s manual for our age. A founder of the futurism blog io9 and the senior tech culture editor at Ars Technica, she has years of reporting on things like genetics, war robots, hackers, and creepy patent practices, particularly by big companies. It has earned her a strong reputation among both the underground and the suits of tech.

And indeed, even the title of her first novel, “Autonomous,” suggests an exploration and a struggle of individual freedom in a highly controlling world. She succeeds to some extent, and there is much to learn even in places where she falls short.

Whether you’ll enjoy what you see and learn about her future of being human is another matter.

The plot is a chase. In 2144, Judith Chen, called Jack, is a freelance pharma hacker, decoding and pirating drugs controlled by companies that have become as powerful as nations (though what we call nations have largely morphed into vague alliances of power). She sells her patent-breaking goods to the masses at affordable prices. When one of her batches, a delightful productivity pill, turns out to be lethally addictive, she embarks on a quest to find a cure, and expose the evil doings of Zaxy, its maker.

Zaxy puts on her tail a Polish mercenary named Eliasz, who is aided by Paladin, a robot that has at her core a small amount of human brain. The action takes place largely in North Africa and Canada, which both retain their respective exoticism and beauty, with an interlude in Las Vegas, which has doubled down on gross exploitation.

In between the considerable episodes of sex (human-human, human-quasi human, human-robot — mercifully, the robots seem to prefer to exchange emoji and shop), there’s much killing. Newitz has a lot to say about the struggle for freedom in an age when, as one character writes, “there has been no one great disaster — only the slow-motion disaster of capitalism converting every living thing and idea into property.” Indentured servitude has made some humans into sex slaves, while certain robots have a limited kind of freedom. Yet no character in the book seems untraumatized, let alone truly free. Even the one elite we meet briefly, the head of Zaxy, isn’t having much fun.

Though she has set her story well and precisely ahead, Newitz is reluctant to move past some present-day ephemera. Early in the book Jack thinks to herself, “What the actual fuck,” a phrase that seems certain to go the way of “gadzooks” and “23 skidoo.” Pirates and hackers are still the cool kids, and their parties still seem to consist of getting wasted and free-form dancing in dark clubs. She’d have avoided the anachronisms by setting the book in an indeterminate near future.

A bigger problem is Newitz’s refusal to explore the moral and emotional implications of even her heroine’s choices. Early on, Jack kills an intruder on her submarine without anything like remorse, or much curiosity about what he was doing there. She does pick up his slave, and has much sex with him before giving him his freedom. (So much for autonomy.)

Jack is supposedly in the drug pirating business to help the poor cure their diseases — but why supply a drug that just makes happy workers? It seems as if she’s making this capitalistic slavery thing worse, and things do go spectacularly wrong: People have such joy in groundskeeping and house painting that they can’t stop, and have to be hauled off, or cause huge accidents and die. And while Jack accepts her role in dumping large quantities of a drug she didn’t understand, whatever remorse she feels is rationalized. Mostly it’s Zaxy’s fault, for making the drug in the first place. Big companies may be bad, but autonomy is uninteresting if it has the moral depth of a program.

The author may know that too. In what appears to be a resolution of the book’s male/female free/slave human/robot indeterminacy, the mercenary and the robot briefly discuss their relationship. Modern readers may approve of the conversation’s therapeutic effect. Even this intimacy feels more like the description of a program than a genuine emotional shift, with no deep exploration of what it means to expose some of our closely guarded privacy in a moment of shared vulnerability — that thing that used to be called love. If it exists in Newitz’s future, this is more of a hope than a reality.

But, as they say these days, here we are.

Quentin Hardy is director of editorial at Google Cloud, Google’s enterprise computing and software business. He was previously deputy technology editor at The New York Times, and has worked at Forbes and The Wall Street Journal.