In the Letters of an ‘Imbecile,’ the Sham, and Shame, of Eugenics

Carrie Buck faced the surgeon’s knife on October 19, 1927 — exactly 90 years ago. Several months earlier, the United States Supreme Court had upheld Virginia’s eugenics law in the case of Buck v. Bell, which validated state laws that sanctioned the practice of eugenic sterilization. Carrie was the “Buck” eventually operated on by “Bell” — Dr. John Bell, superintendent of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, where the sterilizing operation was carried out. What most of the world knows about Carrie Buck is what Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes said of her family in that case: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

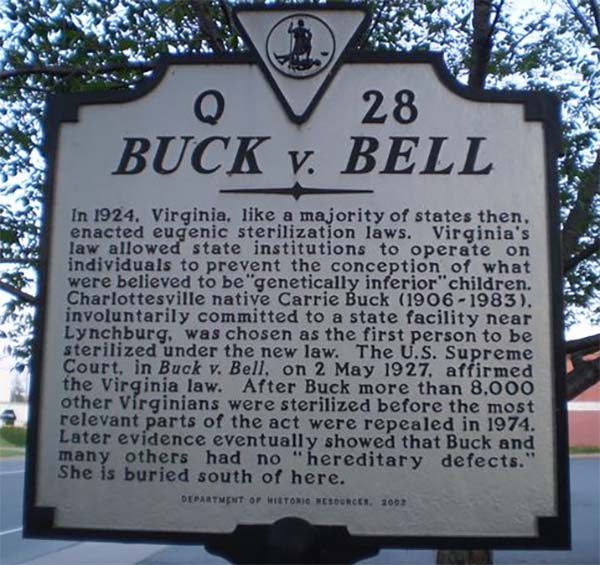

A historical marker in Charlottesville, Virginia, tells the story of Carrie Buck.

To reporters, scholars, and pundits of the era, Buck was, at best, a “poor unfortunate” and “feebleminded girl,” and at worst, a “moron” whose “moronishness,” The Daily Republican newspaper of Monongahela, Pennsylvania put in in 1940, “made her famous — for a day.”

We now know that the Holmes opinion was both cruel and false — and is contradicted by a historic marker in Charlottesville, Virginia that has nothing to do with the Civil War, or the soldier-on-horseback monuments that have generated so much controversy recently. This much more obscure marker recalls Buck’s case and declares that she had no “hereditary defects.” Instead, she was the victim of a sham trial that began her trip to the Supreme Court, and provided justification for 60,000 poor or disabled people in 32 states who were sterilized under laws similar to Virginia’s Sterilization Act of 1924, which aimed to prevent people diagnosed with “insanity … idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness or epilepsy” from reproducing.

We also now know that Buck left her own record — and it, too, rebuts both the Supreme Court’s opinion, and the slurs she endured all of her life.

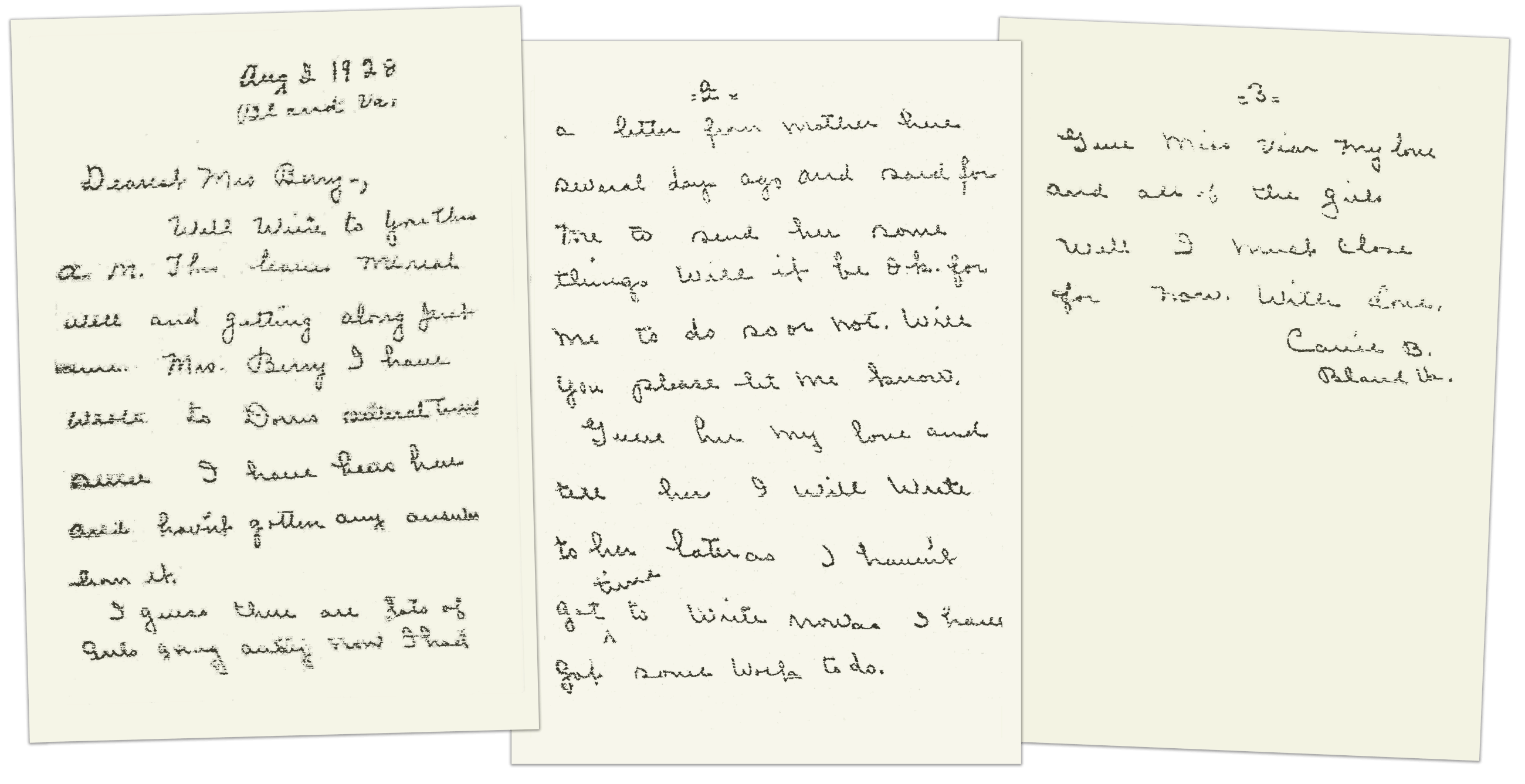

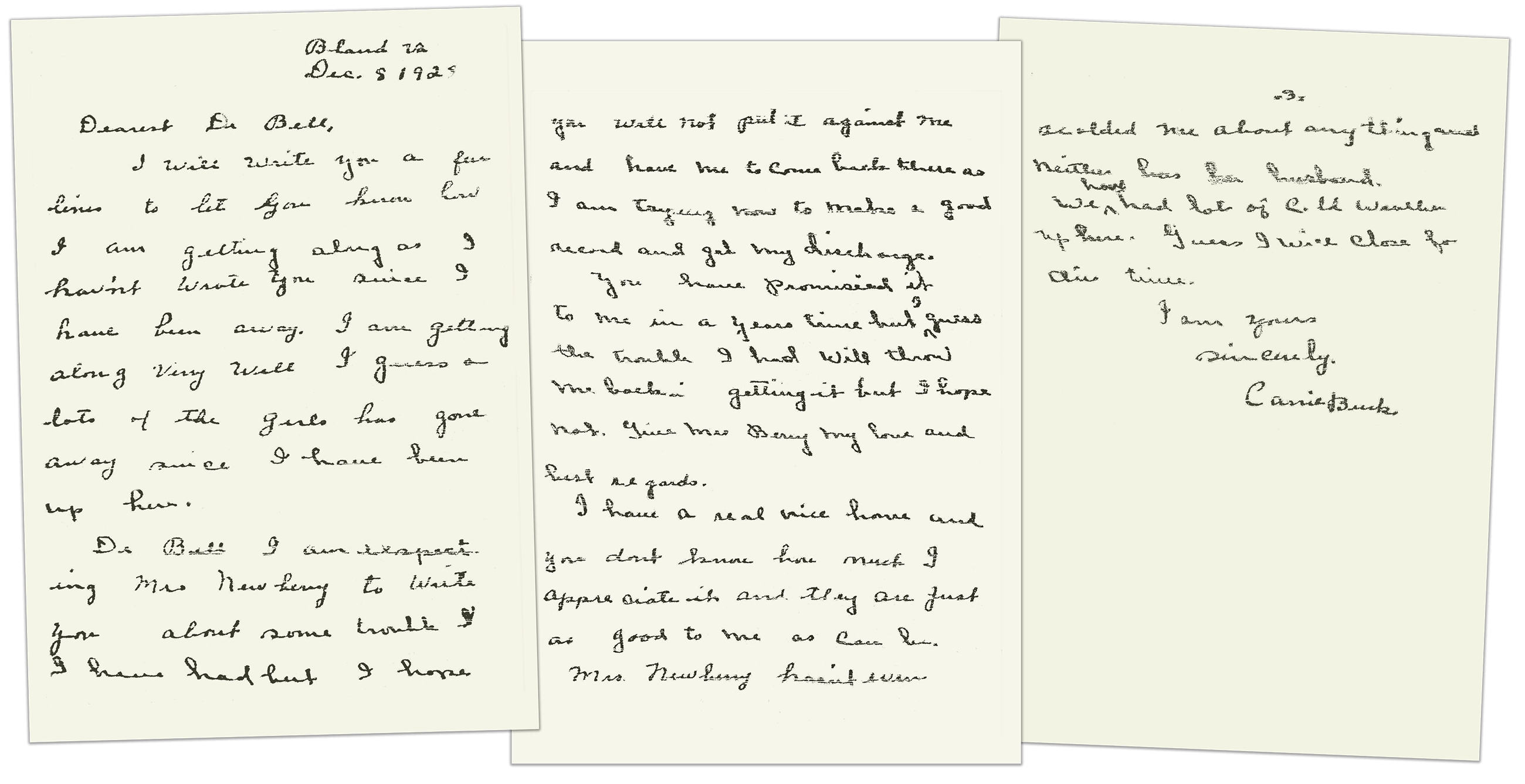

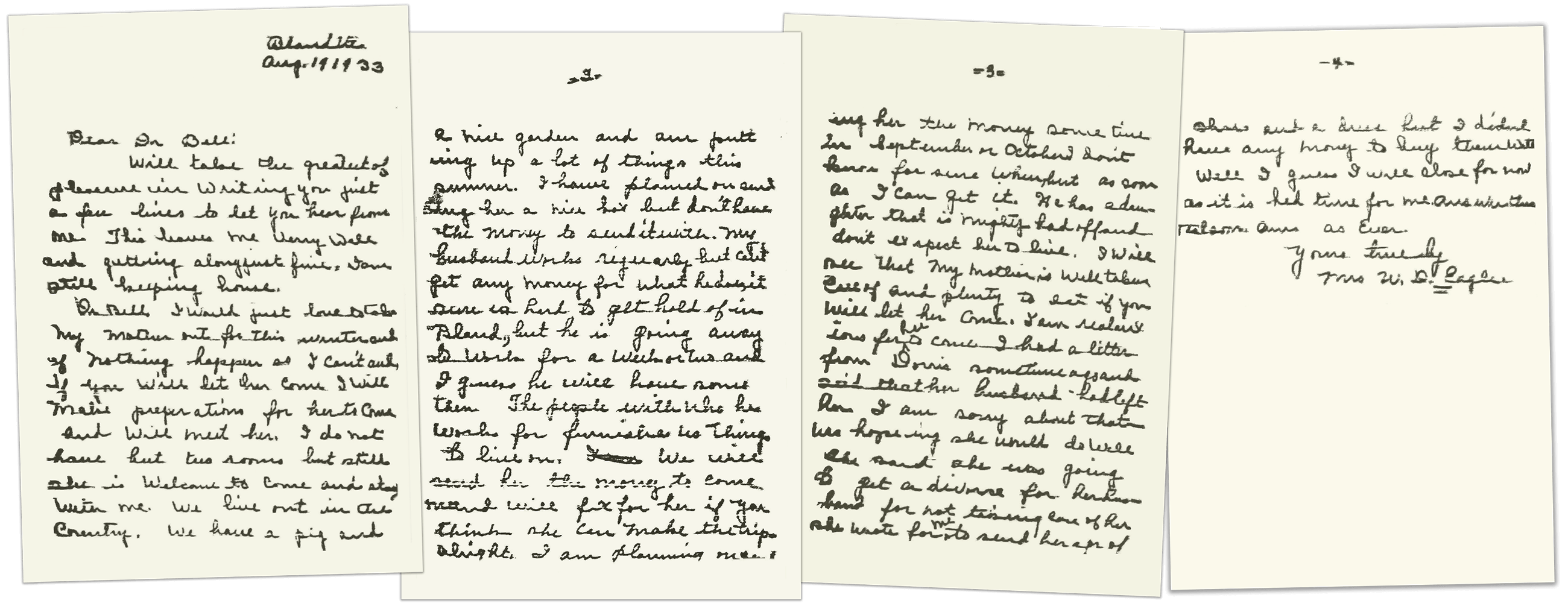

From 1927 until 1934, Carrie Buck wrote at least eight letters, mostly to Dr. Bell and Roxie Berry, the nurse who assisted Bell during the sterilization surgery. Those letters are the footnote to the historical marker, and they speak to us in her own voice in the way a monument never could. For three years, Buck was a “furloughed inmate … on parole,” subject to recall at the first sign of trouble. The letters clearly show Buck’s awareness of her plight: She depended on Colony officials for her continuing freedom, and could be sent back there on short notice.

Buck repeatedly petitioned for her release, reminding Bell of promises he had made to that effect. Instead, in 1928 she was made a ward of her employers, Mr. and Mrs. A. T. Newberry, for whom Buck provided live-in domestic work until her formal discharge in 1930. Buck’s marriage in 1932 eventually provided the evidence of moral and social stability that would win her complete emancipation from Bell’s custody and her employers’ control.

In 1947, the State of Virginia had all correspondence and medical records of “inmates” at the Virginia State Colony copied onto microfilm. In the 70 years since that process was completed, the records have deteriorated significantly. Working from the nearly illegible microfilm records, I restored three of the letters Carrie Buck wrote in cursive script. These letters, and the medical record of Buck’s sterilization surgery, have never been published in facsimile before.

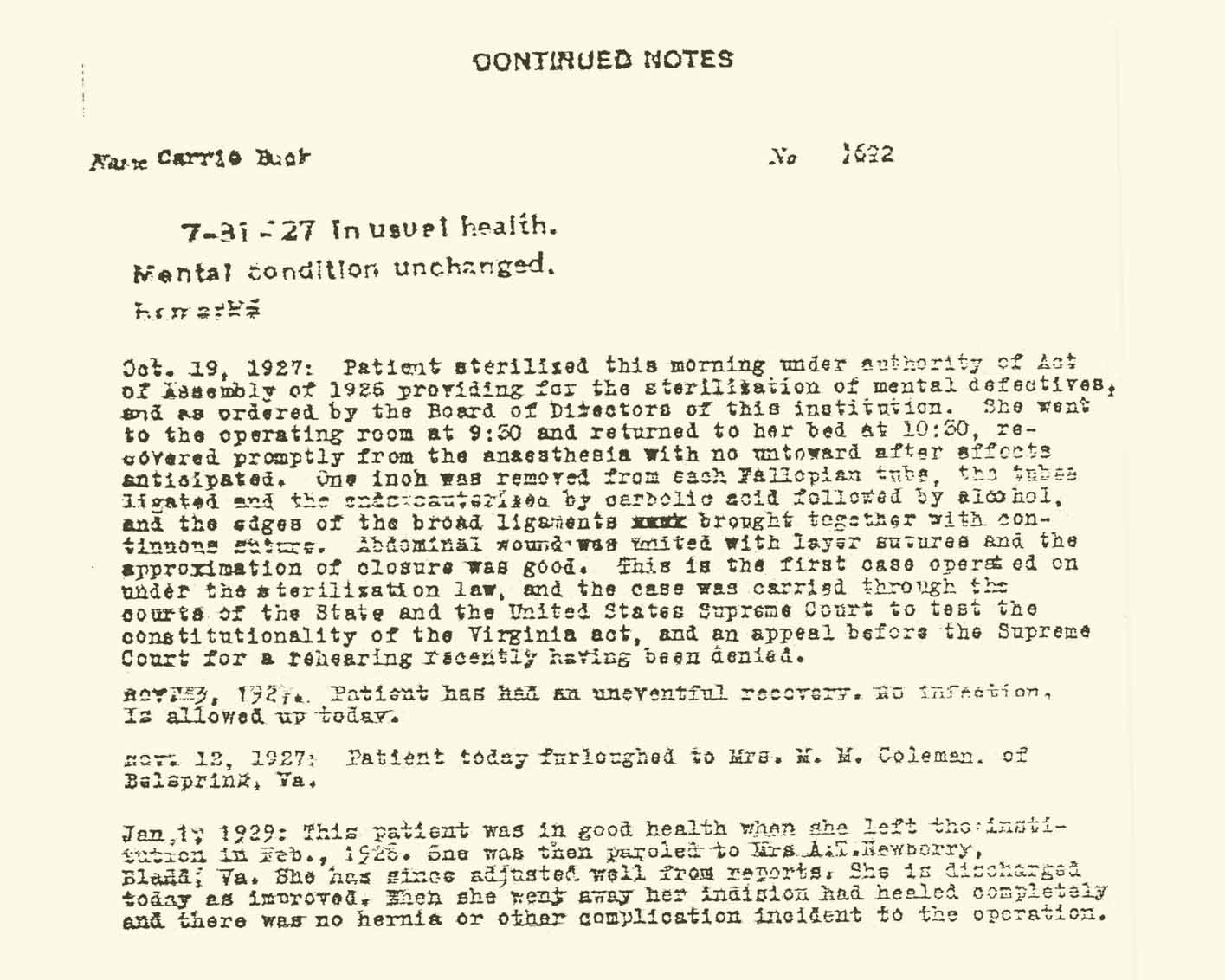

The “clinical notes” describing the operation are remarkably brief, focusing almost as much attention on the legal significance of the surgery as they do on medical details. Buck’s sterilization was accomplished by removing one inch “from each Fallopian tube, the tubes ligated and the ends cauterized by carbolic acid followed by alcohol.” Dr. Bell noted that the recovery was “uneventful” and just over three weeks later Carrie Buck left the Colony.

But the letters tell another story, giving us a glimpse into the details of a simple, hard life.

Buck worked as a “domestic servant” who was paid five dollars per month, though during her more than three years at the Colony, she had become reacquainted with the mother from whom she had been taken as a child, and who had also been committed to the asylum. Buck’s letters contained regular queries about her mother, whose health had been very unstable. Less than a year after she left the Colony, Buck wrote to Roxie Berry, and her concern for her mother is obvious: “I had a letter from mother here several days ago and said for me to send her some things. Will it be o.k. for me to do so or not,” she queried on August 2, 1928. “Will you please let me know. Give her my love and tell her I will write to her later as I haven’t got time to write now as I have got some work to do.

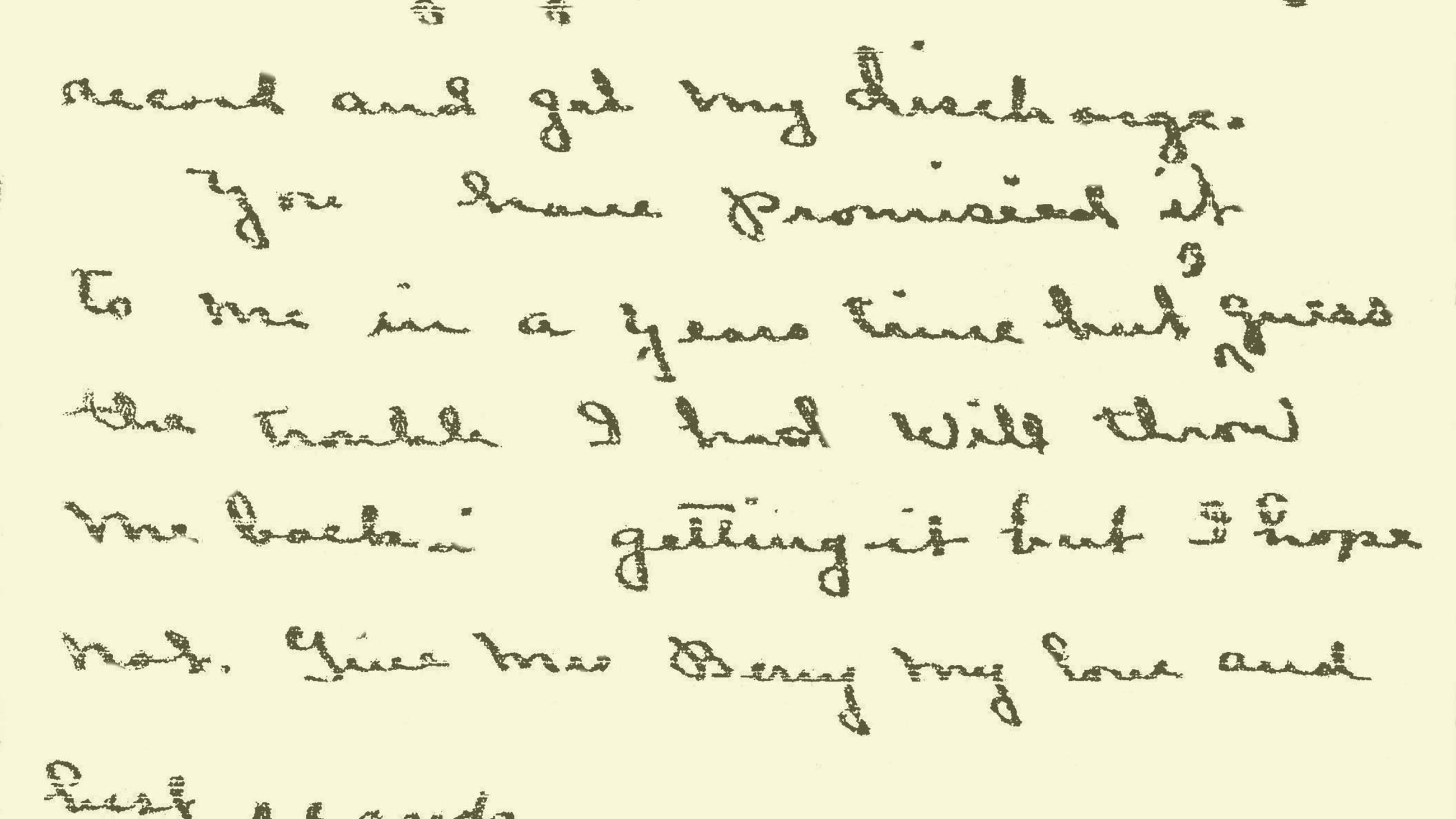

Buck sometimes included pleas for her release. In one case, she sent a preemptive letter to Bell to alert him that he might hear a bad report about her: “I am expecting Mrs. Newberry to write you about some trouble I have had,” she wrote on December 8, 1928, “but I hope you will not put it against me and have me to come back there as I am trying now to make a good record and get my discharge.”

In 1933, a year after marrying the widower William D. Eagle, Buck returned to the subject of her mother, offering Dr. Bell a plan to move her out of the Colony:

Dr. Bell I would just love to take mother out for this winter and if nothing happens so I can’t and if you will let her come I will make preparations for her to come and will meet her. I do not have but two rooms but still she is welcome to come and stay with me. We live out in the country. We have a pig and a nice garden and are putting up a lot of things this summer. I have planned on sending her a nice hat but don’t have the money to send it with. My husband works regularly but can’t get any money for what he does … We will send her the money to come there and will fix for her if you think she can make the trip.” (August 19, 1933)

That letter in full:

By 1940, Carrie Buck had been married for eight years. She wrote the new Colony doctor, inquiring about her mother. “I would like to hear from her, and to find out how she is, and if she is well … to send her a box.” (October 25, 1940) The doctor replied, describing Carrie’s mother Emma as “well and hearty” and “happy most of the time.”

Still, Emma Buck’s health declined steadily and she died in the spring of 1944. Carrie did not receive the telegram announcing her mother’s death. She traveled to the Colony two weeks later, only to find on arrival that her mother had already been buried in an unmarked grave in the Colony cemetery. When Carrie and her half-brother Roy heard the news, the doctor in charge said “they were a bit upset. However, they were most considerate and accepted the explanation.”

Carrie Buck died in 1983 at the age of 77 — 56 years after her sterilization.

Paul A. Lombardo is the author of “Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court and Buck v. Bell.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I wrote a response, as a disabled person who has researched Carrie Buck in college, including reading her letters. I feel that too many people use the logic of her being “mentally normal” as the reason it was wrong to sterilize her, rather than unequivocally saying all sterilization is wrong.

https://kpagination.wordpress.com/2017/10/06/carrie-bucks-letters-and-denying-her-agency/

“It is a disingenuous claim to say he is presenting a new angle on an untold story…

…Buck’s story is albeit being told in flawed ways: the narrative of her being “mentally normal” as the reason it was wrong to sterilize her. It is a narrative that journalists and scholars have done little to correct…

…To say that Buck’s thoughts have never been known before, to say that we just now know “Buck left her own record,” is to say that we did not know before that Buck had agency. To use Buck’s letters to promote a narrative that fails to acknowledge that eugenicists used disability, real or not, as a reason to sterilize people – is also wrong. To use Buck’s letters as proof of “not disabled” meaning she shouldn’t have been sterilized is wrong…

…It is not only insulting to disabled people, but it is also insulting to Carrie Buck and what she went through. Carrie Buck was sterilized under a government law by people who used public fear of disability and “defectiveness” to do it. It was not for people to claim “not disabled” was the one quality that made her sterilization wrong. It was not for people to deny her agency.”

How disgusting, to forcibly sterilising a woman because she is under educated,through no fault of her own. The crimes of America politics is well documented, will the politicians never learn. The shooting by the police of innocent black men and boys. Also the gun laws, which facilitate the massacres of school children, concert goers ect. It’s time the USA got its act together and join the civilised world

How can you put this unsubstantial comment on this site? Isn’t undark supposed to be scientific?

The reasoning for Eugenics were very clear in those times, way, way back in the days. To some extenx still find their way in US laws, yes. Abortion would be an interesting one, love to see you substantiate a pro Or con statement taking Eugenics into the equation and be able to end again with “its time the USA got its act together and join the civilised world.

In my opinion the most frightening part of your comment is how you pull in the racism/police violence into the equation, and without hesitation tell “its time the usa got its act together and join the civilised world. The fact of mixing in “innocent black men and boys” when eugenics are on the table, does not second guess your biased opinion and in my mind already shows that your motives are flawed. If you want to solve anything in this world it has to be one step at a time, for sure needs to be less biased in opinion and for sure has te be kept on topic. Otherwise you will keep fixating on symptoms rather than problems. Which is actually like donating money to a third world/developing country… again I feel tour reasoning represents everything wrong with America