In January 2007, a 12-year-old boy named Deamonte Driver developed a toothache. Six weeks and two emergency surgeries later, he was dead. Bacteria from the abscessed molar had spread to his brain. It was a medieval death, but not as uncommon as you might expect in 21st-century America, where 100 million citizens — nearly a third of all Americans — have little or no access to dental care.

BOOK REVIEW — “Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America,” by Mary Otto (New Press, 304 pages).

His mother, who was on Medicaid, had spent the previous two months trying to find a dentist for Deamonte’s younger brother, who also had rotting teeth. With the help of an attorney and advocate for homeless families, 26 local dentists were contacted on a list provided by state Medicaid agency. But despite being on the list, all of them said they didn’t take Medicaid patients.

Deamonte’s story, told by Mary Otto, landed on the Metro page of The Washington Post. A Post staffer at the time, Otto grew so outraged by the inadequacy of dental health in the U.S. that she’s pursued it to its festering roots for “Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America.” (Otto is an alumna of the Knight Science Journalism fellowship program, which publishes Undark.)

As Otto convincingly points out, healthy teeth are an unspoken prerequisite for school performance, job readiness, social mobility, even adequate sleep. Unhealthy dentition, searing pain, and tooth loss are compounded by shame. Despite fluoridated water in many municipal systems, tooth decay remains the most prevalent chronic health problem in America.

It’s a tale with some familiar villains: a gaping class divide, government officials allergic to social medicine, and Americans themselves, helpless at the twin altars of a lousy diet and poor cash flow (see Villain No. 1). But through dogged documentation and historical telling, Otto also finds a larger and subtler source of rot: the dental profession itself, too often territorial, defensive, and greedy.

State dental boards have stymied legislative efforts to expand the skills and power of hygienists and “dental therapists” who could be usefully and efficiently deployed, much like nurse practitioners, to the vast heartland of dental deserts. Poor counties in America have alarmingly few dentists. Fewer than half of dentists accept Medicaid patients, and when they do, many confine them to a small slice of available time when they will not run into higher-paying clientele.

In their defense, the dentists argue that state reimbursements are inadequate, that they carry high overhead and student debt, and that empowering hygienists would lead to substandard care. They have a point on the first complaints, but Otto finds that in the few areas where nondentists have been trained and deputized to extract teeth and administer preventive treatments on their own, such as among remote native communities in Alaska and in parts of the rural South, the track record of these caregivers — largely women — is impressive.

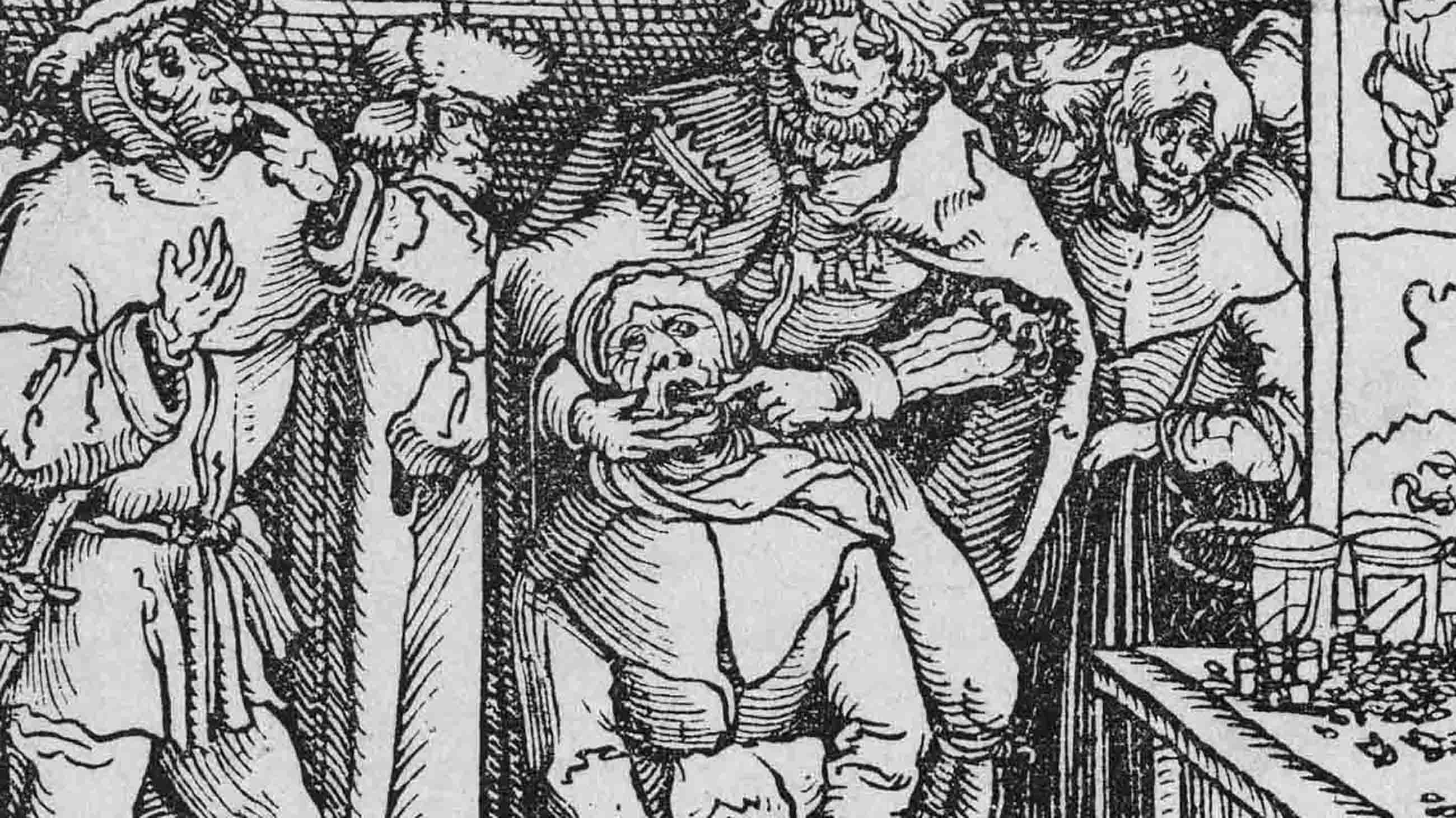

What caused dentistry to veer so far from public health even as other medical professionals took up the banner? The essential problem as Otto describes it is a confounding bifurcation of the teeth and the rest of the body. From the founding of the first U.S. school of dentistry in 1840, dental health was considered a totally separate specialty fueled by mutual distrust between dentists and doctors. Where doctors affiliated with hospitals, dentists bunkered in private practices, a pattern that continues today. Dental insurance policies are separate from medical ones and are optional. And most emergency rooms, where the poor end up, do not have consulting dentists.

To be sure, the social problems of dentistry are also rooted in public policy. Fully a third of Americans do not have dental insurance of any kind. Consider Medicaid, on which 72 million Americans depend. In more than half of states, Medicaid does not offer dental benefits to adults. A legacy of Obamacare is that the program is now supposed to guarantee dental care to children, but in reality only half of children receive it. And Medicare, which covers 55 million seniors, has never offered routine dental care, even though older Americans suffer disproportionately from serious oral health problems.

It’s unfortunate that the book came out in the midst of upheavals in health-care policy and delivery. It feels almost outdated, with much narrative focus on the Affordable Care Act. Otto spends a bit too much time in the weeds, repeating the same facts over and over, such as the percentage of people unable to gain dental care under Medicaid. Although she gives evolution a brief nod, her tale would have benefited from more about the big-picture importance of dentition to human evolution, how molars differ across species and what makes the human versions so unique. But Otto’s lens on policy and social justice is an important one, and she skillfully humanizes the material through stories of individuals on either side of the oral divide: those pursuing expensive, cosmetic treatments, from whitening to pearly Hollywood-style veneers, and those sleeping in their cars, barely able to eat, while waiting for the rare free weekend clinic in Appalachia.

Otto argues that dental health should be considered as much a part of primary care as well-child visits and vaccinations. She makes a compassionate and compelling case. Since Deamonte’s death, and Otto’s own groundbreaking reporting, the state of Maryland has dramatically improved dental access to Medicaid patients. But as “Teeth” attests, there is a long way to go before we can all start smiling proud.

Florence Williams is the author of “The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative” (W.W. Norton, 2017) and “Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

My heart breaks for this mother who lost her child to a condition that deserves treatment no matter how much money you have. If you visit the emergency room with a heart problem, they give you treatment even if you can’t pay right then, because they aren’t allowed to just let you die. Why is dental health any different? These dental issues can be life threatening, so why are they allowed to deny treatment to those who can’t afford their outrageous rates?

My husband and I both suffer from serious dental problems. We are young, in our 20’s, just getting started in life. But we can’t afford the work we need done. I’m on antibiotics now to keep infection at bay, but that’s just a bandaid. We need teeth pulled but may not be able to replace them if we don’t have the money. It’s not right. We’re probably going to Mexico for dental tourism for a fraction of price.

My recent dental experience brought me to this site. My dentist extracted a tooth several days ago, telling me it was the cause of the pus seeping from my gums. This was tooth #28, which the dentist had previously said needed to be extracted and replaced with a bridge or implant. That tooth had a root canal and a crown, and gave me no further trouble. There was no crack visible on the X-ray after extracting it. He said the crack was on the lower portion, which I would take to be the pulp. I saw no crack when he showed it to me. How he failed to notice that most of the pus was coming out of tooth #30, and that there was a dental fistula below tooth #30 that was causing the infection I’ll never know. I had made two previous visits to his office to make sure that that bump wasn’t oral cancer and he assured me that it was just a harmless tori. On the day I went in to have #28 extracted he seemed surprised to discover a fistula under #28. There is no other bump there that I’m aware of. So now, instead of extracting #30,which is in a less conspicuous place, and might not even have to be replaced, I’m now stuck with an ugly deformity which will be very expensive to repair. Since i’m planning to leave the country for a month long vacation in October, I declined his offer to extract #30 as well. Although I’m taking an antibiotic so slow the infection I know that’s no cure. There is still pus seeping out around #30 and that’s not a very enjoyable state to be in while on vacation. Don’t know if this an appropriate post for this site, but I thought I’d give it a try. Sorry about the grim details.

I can see the pro dentist leanings in some emails.

Why the dentist lobby doesn’t let the dental hygienists take over some responsibilities…a pro patient step as it would reduce some cost in dental health.

Please… let’s not get bogged down in the fluoridation debate yet again. Instead, let’s get our “representatives” to improve healthcare in all ways, including, of course, dental care, which, as the article shows, is another essential need which is not being met.

Translation. Dentist don’t want people that will sue them . Have a little dignity and u might someday be accepted instead of tacking everything from other people’s hard work the blaming them for all your problems

Fluoridation (Fluoride) is poison – check the poison warning label on the back of your fluoridated toothpaste – hence not the dental miracle ‘vitamin’. Rather, wholesome diet is the key to healthy teeth.

Non-leeching direct to enamel topical fluoridation (ex – varnish) is somewhat beneficial ; general (systemic) dietary fluoridation (ex – fluoridated water) not so much. General dietary fluoridation interferes with many necessary essential nutrient absorptive and metabolic processes.

Anything is poison if you take too much of it, including multivitamins. Check those labels too.

Lording it Loony Logic

Fluoridationist: Fluoridation is needed because poor kids don’t have access to dental care.

Sane person: If politicians, dentists, and public health officials care about poor kids why are they excluding them from dental services?

Fluoridationist: The poor should be grateful for fluoridation because it’s dirt cheap and it’s all they’re going to get.