In Appalachia’s Foothills, a Leaner Textile Industry Rises

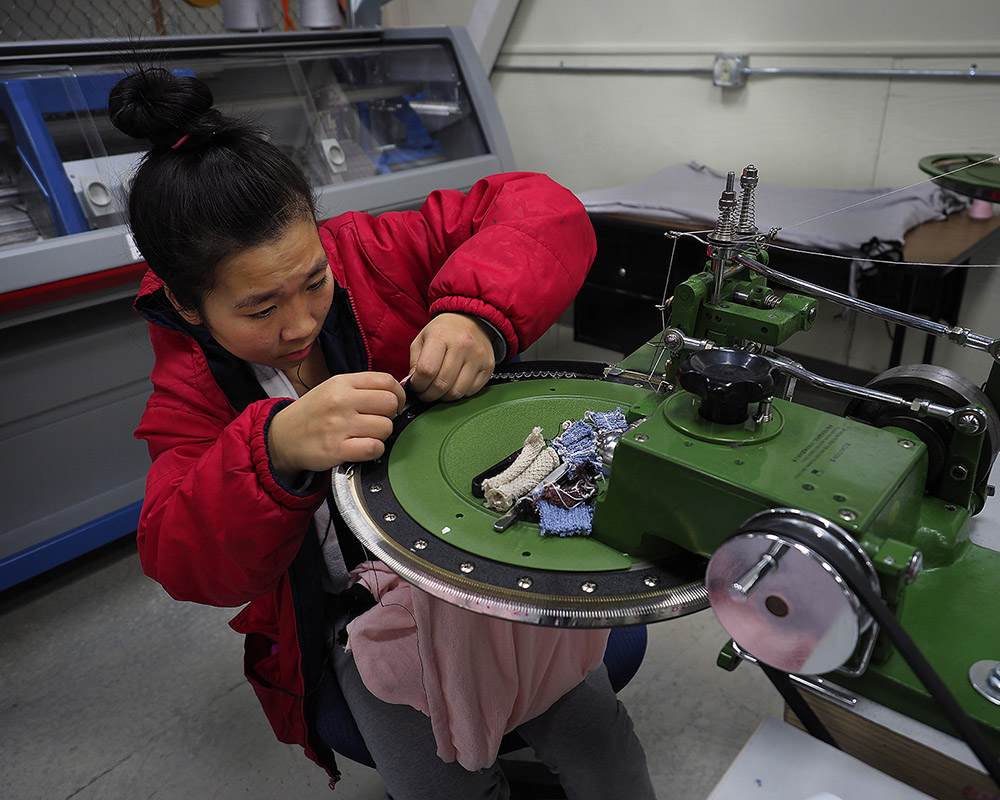

The cavernous manufacturing room at InnovaKnits, a contract producer of knitwear in Conover, North Carolina, is empty save for four large flat-bed knitting machines, four linking machines, and four women. German-made Stoll machines knit like lightning, turning out bodices and sleeves for women’s sweaters. The workers deftly hook loops of yarn one by one over tiny pins on the linking machines, which seamlessly connect the sleeves to the bodices. It’s a tedious task and one of the last remaining jobs done by hand here.

“We might be able to take something off the machine so that it requires only one step of labor instead of 10 steps of labor,” says Jason Wilkins, co-founder and managing partner of the company. “Everyone knows the future is to do as much on the machine as possible,” he added.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

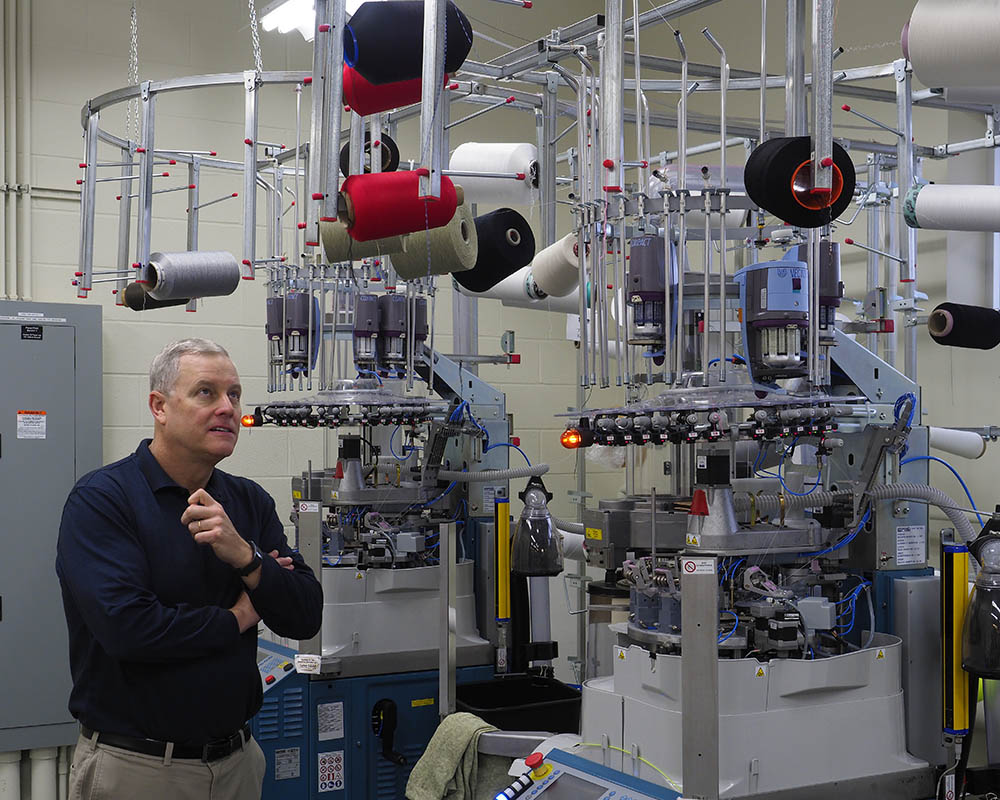

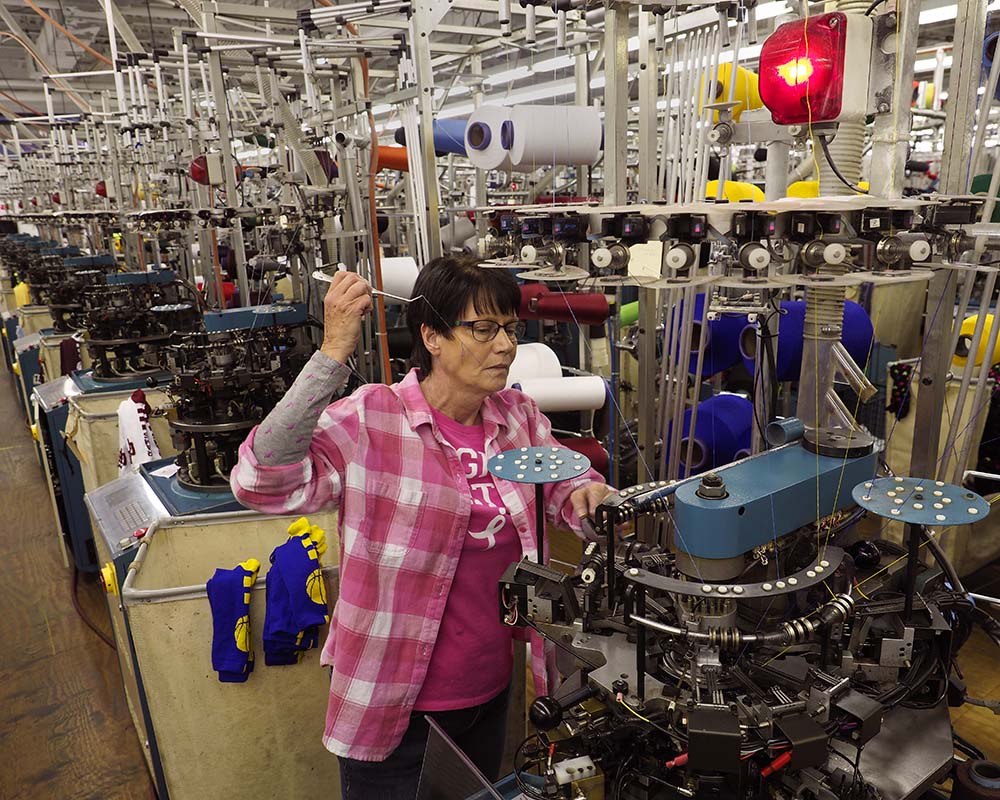

Catawba County, North Carolina — a former textile production powerhouse decimated by offshoring — is enjoying a renaissance fueled by innovation, high-tech materials, automation, and custom work. Textiles are coming back here, but not the old jobs. “The state-of-the art plant in 1990 had line shafts with a leather belt running the knitting machines. Now we have robots closing the toes and that eliminates half the plant,” says Dan St. Louis, executive director of the nonprofit Manufacturing Solutions Center, a division of the Catawba Valley Community College.

The Manufacturing Solutions Center was established 27 years ago to transition hosiery workers from mechanical to electronic machines. In the textile mills, St. Louis recalls, well-paid employees known as “doffers” still raced around the spinning room replacing bobbins, a physically demanding job that could take 20 minutes per machine. Automation cut the chore down to two minutes and eliminated the doffer, just one of the many textile jobs that have disappeared from the scene.

Today, mills today are hiring computer designers, software engineers, and people trained to program and operate the increasingly complex knitting machines — an in-demand job that can command a salary upwards of $80,000. The Manufacturing Solutions Center specializes in applied research and development, prototyping, testing, domestic sourcing, and of course, training for 21st-century textile jobs. “Our whole purpose and mission is to help create jobs here in the U.S. — bottom line,” says St. Louis.

In many ways, this is the story of manufacturing across the South, where automation is giving American companies, large and small, the edge needed to compete with cheap labor overseas. Made-in-America sentiment, along with rising wages in China, shipping charges, and tariffs are added incentives to do business at home for some large companies.

These include Walmart, which announced plans in 2013 to source an additional $50 billion worth of American-made goods over the next 10 years. Foreign investors from China, India, Canada, and Germany, among other countries, have opened or announced plans for factories in the South, attracted in large part by quality production, more manageable supply chains, and cleaner, less polluting technology. American mills, likewise, are selling their threads and textiles to factories in China and Southeast Asia.

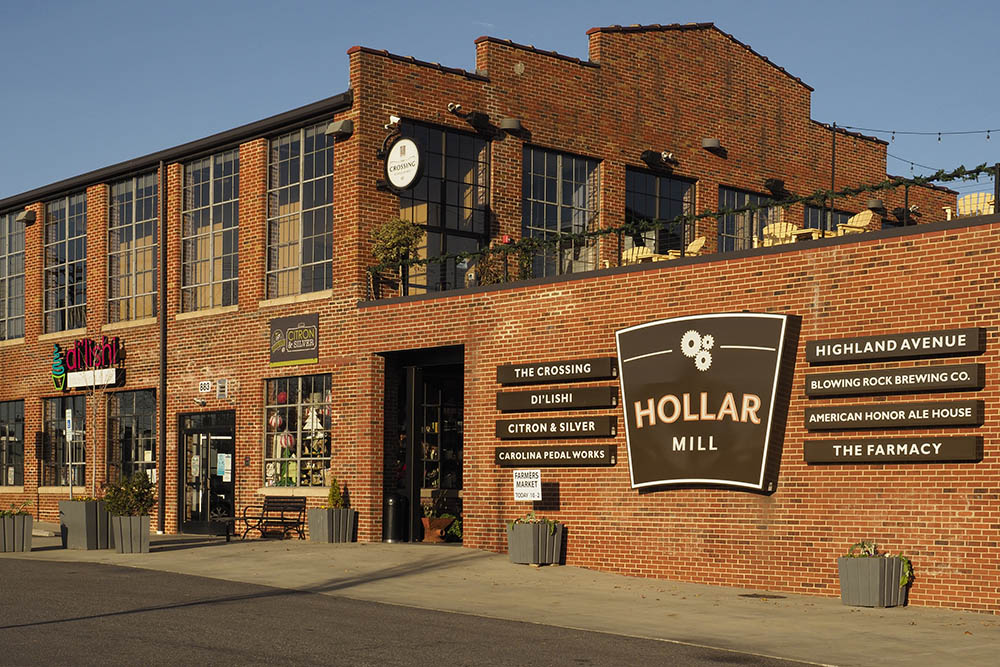

Here in Catawba County, in the foothills of North Carolina’s Appalachians, inventors in the Manufacturing Solution Center’s business incubator are developing top-secret, futuristic fibers. And old-line knitting companies are solidifying their hold on niche markets with rapid delivery and custom production made possible by automation.

“They’ll say that we’re doing three times as much volume with one-third of the people,” says Nathan Huret, director of existing industry services for the Catawba County Economic Development Corporation. He adds that some of the mills are running 24/7, and “are more efficient, producing more and making better margins on some of their products.”

For all of this, the American textiles industry is still a shadow of its former self. In 1973, 2.4 million people worked in the textiles and apparel industry, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics. By 1996, that number was down to 1.5 million and dropping — fast. Between 1990 and 2016, the two industries combined lost almost 80 percent of their jobs, with 385,000 remaining today.

North Carolina, the nation’s leading textile producer, mirrored the national decline, losing 85 percent of textile jobs, from 284,000 in 1992 to just over 42,000 today, according to Bureau of Labor statistics. Catawba County, a textile center in a textile state, suffered a similar fate, going from 12,000 textile-related jobs in 1992 to just under 1,500 today, according to the Catawba County Economic Development Corporation. There were 156 textile-related companies then; now there are 48. With its furniture and fiber optic cable industries also taking a hit, the county’s unemployment rate skyrocketed from just over 2 percent in the early 1990s to 15 percent during the worst years before recovering to a current rate of 4.8 percent.

The state’s textile revenue, not surprisingly, fell to less than $3 billion in 2014 compared with an inflation-adjusted $7.5 billion in 2000, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

At the same time, worker productivity in North Carolina has increased dramatically, up 61 percent from an inflation-adjusted $43,731 per worker in 2000 to $70,709 per worker in 2014, according to calculations derived from Bureau of Labor Statistics data. “It isn’t that we have to produce 10 times as much as we used to make. It’s that each thing we produce has to be worth 10 times more,” says Brad Seese, product development and brand manager at Fiber & Yarn Products in Hickory.

The mid-sized yarn company, which was established in 1980, reinvented itself to capitalize on the growing demand for technical fibers. Among its proprietary products are moisture-wicking yarn, a fiber that reduces friction, and a sewing thread innovation to reduce or remove torque to enable seaming machines to run faster. A single case of the company’s high-performance yarn sells today for as much as an eight-case pallet of ordinary yarn brought in 2000, Seese said.

“We keep looking for new ways to advance what the consumer is asking for,” says Seese.

Textile-Based Delivery Inc., one of the startups in the Manufacturing Solutions Center business incubator, is developing fabrics designed to deliver controlled doses of medicine and other active ingredients. Jordan Schindler, the company’s 25-year-old founder and CEO, conceived the idea of infusing a pillow case with acne medicine while he was in college. Today, he’s talking about T-shirts that treat shingles and socks that control athlete’s foot. “Smart fabric,” says Schindler, “is where the industry’s going.”

Twin City Knitting in Conover, meanwhile, has been making socks for almost 56 years and still makes the same athletic tube sock it made in 1977. What’s different are the Italian-made knitting machines and computer software programs that enable the company to design and weave custom logos into socks for sports teams from Little League to collegiate sports. They can run a batch with as few as a dozen pairs, delivery by game day guaranteed.

“Do we compete with Nike, Under Armour, Adidas? Sure,” says company president Francis Davis. “But we’re the other guy because we can do small runs. We’re local and we have a strong customer base. We’re in your high school and my high school and the university.”

Of course, no one expects labor-intensive, large-scale garment manufacturing to return to the United States any time soon, but small cut-and-sew operations like Opportunity Threads in nearby Valdese are springing up to meet a growing demand for custom and small-batch production. The worker-owned company makes memory-quilts from old rock concert and logo T-shirts, turning out 600 to 700 units a week.

“I had just watched growing up in this community where one plant would shut down on a Friday … and on Monday, there were 500 people out of work,” says company co-founder Molly Hemstreet. “I said we need to do something different. We need to not rely on people from the outside to always find our solutions.”

Hemstreet sees a sustainable future for companies like hers that focus on a triple bottom line — environmental, social, and financial — to build equity at home. Catawba County’s Economic Development Corporation’s Huret concurs. “I am very bullish on textiles’ future,” he says, “especially here in this community.”

Funding for this project was provided in part by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Larry C. Price also contributed reporting for this article.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It’s really nice that some people are coming up with interesting, innovative products and all, but the brute numbers say those are niches. The success stories build to an upbeat conclusion, but employment levels in the sector are still like one fifth what they were before. Local innovation is good, certainly better than nothing, But it is not a substitute for an industrial policy, which today in most wealthy countries has been dropped in favor of letting production go to the lowest wages.

FAQ “copied from Threads site) “Most of our workers are currently Mayan immigrants that now call Morganton home. The Maya of Morganton have a long and vibrant history in our community. Many came during or after civil war wreaked havoc on their native communities in Guatemala. You can read more about this incredible community in the book The Maya of Morganton, by Opportunity Threads friend and supporter Leon Fink.”

What a thoughtful, well-written piece that helps dispel the myth that textiles are dead in the American South. I am proud to be a citizen of this community where innovation and reinvention is taking place. Instead of wringing our hands in despair, weeping for the “old jobs” to return, we got busy putting a new twist on traditional industries. We are going places, and institutions like Catawba Valley Community College with its Manufacturing Solutions Center, are taking us there!

Since I sew and enjoy all the new fabrics especially all the various colors out there, this is such a great opportunity for people to start learning a new trade.

Thanks for reporting this. The general populace needs to know that textile manufacturing is not dead in North Carolina or the nation and, in fact, is thriving again.