Two weeks before Christmas 1999, Lee Hood appeared to have it all: A loving family. Money. Fame. Power. He counted Bill Gates, one of the world’s richest men, as a friend and supporter. Eight years earlier, Gates had given the University of Washington $12 million to lure the star biologist from Caltech in what the Wall Street Journal called a “major coup.”

The accompanying article is excerpted from Luke Timmerman’s new book “Hood: Trailblazer of the Genomics Age. To pre-order a signed hard copy, purchase the Kindle eBook edition, or purchase as a PDF download, visit TimmermanReport.com

Hood’s assignment on arrival: build a first-of-its-kind research department at the intersection of biology, computer science, and medicine.

Even at 61, the former high school football quarterback could still do 100 pushups in a row. He ran at least three miles a day. He climbed mountains. He traveled the world to give scientific talks to rapt audiences. At a time when many men slow down, Hood maintained a breakneck pace, sleeping just four to five hours a night. He owned a luxurious art-filled mansion on Lake Washington, but otherwise cared little for the finer things in life, sporting a cheap plastic wristwatch and driving an aging Toyota Camry. Those who worked closely with him said he still had the same wonder and enthusiasm for science he had as a student.

Yet here, at the turn of the millennium, Hood was miserable.

His once-controversial vision for “big science” was becoming a reality through the Human Genome Project, yet he didn’t feel like a winner. He felt suffocated. He had a new vision, a more far-sighted and expansive one that he insisted would revolutionize healthcare. But he felt the university bureaucrats were blind to the opportunity. They kept getting in his way. It was time, Hood felt, to have a difficult conversation with his biggest supporter.

On a typically dark and gray December day in Seattle, Hood climbed into his dinged-up Camry and drove across the Highway 520 floating bridge over Lake Washington to meet Gates, the billionaire CEO of Microsoft. Hood shared some startling news: he had resigned his endowed Gates-funded professorship at UW. He wanted to start a new institute free from university red tape. It was the only way to fulfill his dream for biology in the 21st century.

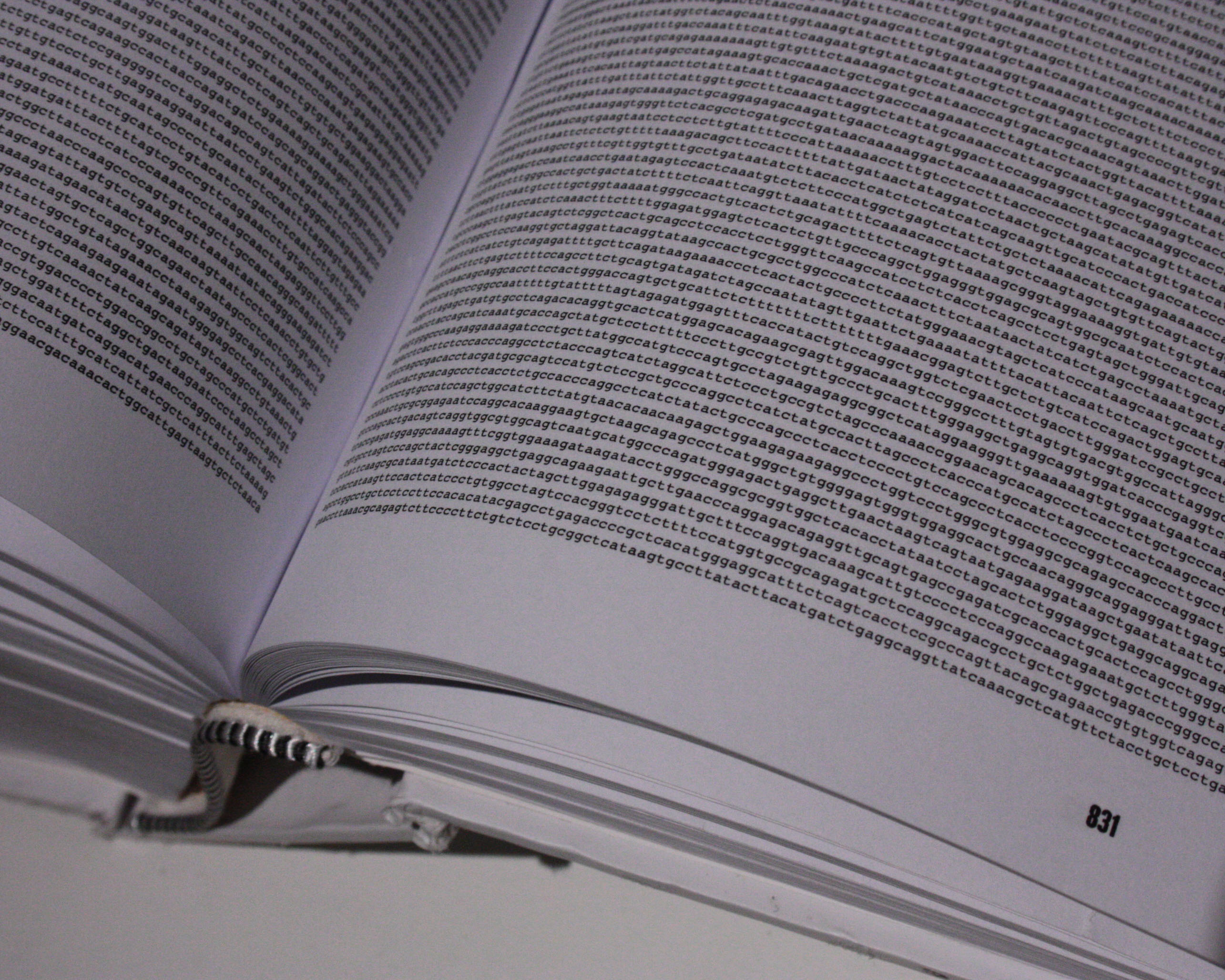

Gates was well aware of Hood’s record of achievements and its catalytic potential. Hood had led a team at Caltech that invented four research instrument prototypes in the 1980s, including the first automated DNA sequencer. The improved machines that followed made the Human Genome Project possible and transformed biology into more of a data-driven, quantitative science. Researchers no longer had to spend several years — an entire graduate student’s career — just to determine the sequence of a single gene. With fast, automated sequencing tools, a new generation of biologists could think broadly about the billions of units of DNA.

The sequences were obviously important, as they held the instructions to make proteins that do the work within cells. Thousands of labs around the world — at research institutions, diagnostic companies, and drugmakers — used the progeny of Hood’s prototype instruments as everyday workhorses. George Rathmann, the founding CEO at Amgen, biotech’s first big success story, once said Hood “accelerated the whole field of biotechnology by a number of years.”

Building on his success at Caltech, Hood had recruited teams at the University of Washington that continued to create new technologies to further medical innovation. One machine analyzed the extent to which genes are expressed in biological samples; another analyzed large numbers of proteins simultaneously. One device quickly sorted through different types of cells.

Hood certainly wasn’t the only biologist looking ahead, imagining what these automated tools could enable. Once scientists had the full parts list of the human genome on their computers, many believed it would lead to greater understanding of disease, paving the way for precise diagnostics and, ultimately, “personalized medicine.” But Hood had an unusually clear and far-reaching view for how biologists could fully exploit the new instruments. His enthusiasm inspired many bright scientists to devote themselves to his vision and to do their best work.

Not that he inspired everyone. Many people throughout his career saw a man who took excessive credit for discoveries made by others, including young scientists who toiled for him around the clock. Critics saw a self-promoting narcissist, someone who could be blind to the ways his actions sometimes hurt people. He had contradictions: Influenced by his teachers, Hood was dedicated to science education his entire career, yet he did little to mentor his own graduate students.

Passionate as he was about his vision, Hood could be strangely detached from the people he asked to carry it out. He had a big ego — an “unshakable confidence,” in his own words, and he thought he was entitled to special treatment, which frustrated university leaders. When people complained Hood was out of control, he usually turned a deaf ear, dismissing them as bureaucrats or whiners. He was quick to point the finger at others when things went wrong, while hardly ever admitting a mistake of his own.

Like many biotech entrepreneurs, Hood made promises he couldn’t keep. He predicted his work would lead to a personalized medicine revolution within a few years. It didn’t. Competitive to the core, he drove himself to stay at the cutting edge. That meant starting multiple projects at once, getting them operational, then leaping ahead to the next thing. He left the slow, painstaking, meticulous work of science to others.

Ever since James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double helix structure of DNA in 1953, biologists had pursued the promise of molecular biology. Scientists spent the last half of the 20th century drilling ever deeper into understanding one gene, and usually the one protein created by that gene’s instructions, at a time. Each gene was studied in isolation. It was a thrilling time, as biologists saw there was an underlying unity to life: the DNA code was present in animals, plants, bacteria — every living organism on the planet. The code held genetic information that had so much influence over life on Earth. Many great discoveries had been made using a narrow, deep approach that sought to understand the meaning of the code in many contexts — different animals, different disease states, different environments.

Hood himself, as a graduate student, carried out important immunology research in this tradition. Yet at the start of the 21st century, Hood believed biology was ready for more ambitious goals. He believed traditional reductionism, looking at one gene at a time, was outdated “small science.” Biology was maturing from a cottage industry into a modern science with fast automated research tools. The time was right, he argued, for scientists to look at hundreds or thousands of genes and proteins together in the complex symphony that makes up a whole human organism with trillions of cells. Biology, like physics, had an opportunity to turn into “big science” — fueled by big money, big teams, and big goals.

The way to tackle such complexity, Hood said, was through what he called “systems biology.” It was a new twist on an old idea that involved bringing scientists together from various disciplines of biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, and computer science. He wanted the power to recruit the right people to the University of Washington for this mission. These people didn’t always speak the same language, but Hood saw himself as the leader who could cross the scientific cultural divide.

He would break every rule and custom of academia if necessary. If he needed to offer a computer scientist a salary that was competitive with Microsoft’s wages, he would. He wanted to choose whom to hire and whom to fire. He needed the flexibility to raise his own money from wealthy donors, some of whom had struck riches in the original internet boom of the late 1990s. If he wanted to out-license a technology for further development to a company, or start a new company, he didn’t want to ask permission. Hood demanded a multi-million dollar facility with enough room for all of his scientists, complete with a floor layout that tore down traditional walls between departments to enable more collaboration. As negotiations at the University of Washington dragged on, Hood realized he wasn’t going to get what he wanted. And university officials were growing weary with his entrepreneurial break-all-the-rules attitude. Hood had approached a wealthy donor without permission. He was actively organizing an independent nonprofit while still on the state payroll. When officials suggested he had run afoul of a new state ethics law, Hood felt threatened and embittered. Abruptly, he quit.

For his final act, Hood wanted to be the boss. New ideas need new organizations to support them, he said. Years earlier, while at Caltech, he had learned this lesson the hard way. Nineteen established instrument companies told him they weren’t interested in developing his DNA sequencer. Hood and some venture capitalists started a successful new company, Applied Biosystems. Emboldened by that experience, Hood now decided he was ready for a whole new kind of risk. In his early 60s, he decided to give up his department chairmanship and tenured faculty position. He had to start his own research institute. It was time to put his money and his reputation on the line.

There were sensitivities that needed to be considered. Would all of Hood’s federally funded grants transfer to his new institute in an orderly manner? How many of his bright students and postdocs would leave an accredited university to join a risky venture? Would peers be supportive, or would they dismiss the institute as a flight of fancy unworthy of grant funding? Could he find lab space? How much of his own money would he need to spend? Would he be condemned by the media for turning his back on the University of Washington?

Many of those questions would take months or years to resolve. But on that gloomy day in December 1999, Hood wanted to break the news to Gates in person. He knew it would be bad form for Gates to hear about it on the evening news. Hood had his assistant call Gates’ office and request a face-to-face meeting. The two men had been close, so Hood got on the calendar. Gates had heard the gist of the institute-within-the-university idea and was curious to hear what was so important that it couldn’t wait.

The men sat down in a couple of comfortable chairs in Gates’ office in Building 8 at the Microsoft campus in Redmond. Hood came quickly to the point. He’d resigned his endowed Gates professorship at UW because the bureaucracy of a public institution would never be flexible enough to let him achieve his goals for multi-disciplinary systems biology. Hardly stopping for breath, Hood barreled through his long list of grievances with administrators who didn’t share his vision. In the same breath, he rhapsodized about the opportunity for systems biology.

The billionaire listened for a solid 15 to 20 minutes. When Gates asked whether the dispute could be resolved some other way, Hood said he had tried for three years to set up such an institute within the university.

When Hood had said his piece, Gates cut to the heart of the matter.

“How are you going to fund this institute?” he asked.

“Well, that’s part of the reason I’m here…” Hood replied.

Gates interjected.

“I never fund anything I think is going to fail,” he said.

Hood was stunned.

He hadn’t expected Gates to commit on the spot to bankrolling a new institute. But he didn’t expect to be flatly dismissed. Gates was a logical thinker, not the impulsive type. He was a kindred spirit, an entrepreneur, a fellow impatient optimist. Years earlier, they bonded on a safari in East Africa; Hood listened to Gates talk about the “digital divide” as hippopotamuses grunted in the night. Often, Gates peppered his biologist friend with questions about the human immune system, widely considered to be the most sophisticated adaptive intelligence system in the universe. The recruitment of Hood helped raise the University of Washington to international prominence in genomics and biotechnology during the 1990s. Given that success, Hood thought he could talk his friend into providing as much as $200 million for a new institute.

Hood didn’t realize it at the time, but Gates was starting to think more seriously about how to make an impact by giving away most of his fortune, by tackling diseases that plague the world’s least fortunate people. By contrast, Hood’s brand of systems biology was abstract, and its applications were likely to come first in rich countries.

The harsh truth, for Hood at least, took years to sink in. Gates didn’t give his institute a penny in its first five years.

Their friendship didn’t end, but the two men would never be quite so close again. “I definitely disappointed Lee,” Gates said years later.

Reflecting on Hood’s split with the university nearly 15 years later, Gates took a nuanced view. He was intrigued by Hood’s new vision, but he also saw why he didn’t work well with others in the university. “He’s a wonderful guy, but a very demanding guy. He’s kind of a classic great scientist,” Gates said. “These things are never black and white.”

On the drive home that fateful day in December 1999, Hood wondered whether he had said something wrong, failed to make a case. But it was a fleeting emotion. Moments of self-doubt, to the extent he had them, were brief. He confided in his wife, Valerie Logan, the one person he knew would give him the support he needed, no matter what. He brooded for a while. “It shocked and hurt me,” Hood said. “It was a statement of skepticism from someone I had hoped would support me.”

Others who were close to the situation understood why the meeting had gone badly. “Bill had not, at that time, been schooled in philanthropy,” said Roger Perlmutter, a former student of Hood’s who went on to run R&D at Amgen and Merck. “This gift to the University of Washington to create Molecular Biotechnology was surely the biggest thing he had done in philanthropy. It was all done to bring Lee here. And then in short order, it unravels? It was a kick in the teeth.”

If Hood’s first thought was that he had possibly damaged his relationship with his most important benefactor, his second thought was that his vision was right and he needed to find other support. He had some money already. Much of it was through his shares in Amgen, the biotech company he advised from its early days, and which had become one of the best performing stocks of the 1990s. He’d also made millions from royalties on DNA sequencers sold by another company he helped start — Applied Biosystems. And Hood had other wealthy friends and companies he could call on for help.

There was a lot to think about beyond science. Where to begin on starting a new institute? Even though he was hailed as one of biotech’s great first-generation entrepreneurs, Hood had never played an executive role in running those enterprises. Now, he would have to act as a startup CEO responsible for not just vision and fundraising, but day-to-day operations. He knew he wasn’t a skilled administrator. He was impatient in meetings, lacked empathy, and made clear to all around him that he didn’t want to hear any bad news. He had a bad habit of avoiding sensitive personnel matters, like whether to fire people.

None of that deterred him. Hood’s son, Eran, an environmental scientist, once said of his father: “He’s always sort of had this narrative in his life of him struggling against people who are trying to keep him from doing what he wants to do. I always joke they should take the Tupac Shakur song, ‘Me Against the World’ and rewrite it as ‘Lee Against the World.’ They could take out the district attorneys and the crooked cops and put in university presidents and the medical school deans who just don’t know, don’t understand, his vision.”

The path ahead was clear. Hood had to prove his vision was right. He would push himself around the clock, to the far ends of the Earth, spend his last nickel. Nothing, he was determined, would get in his way.

Luke Timmerman is the founder and editor of Timmerman Report, a subscription publication for biotech professionals. He is also a contributing biotech writer at Forbes, and the co-host of Signal, a biweekly biotech podcast at STAT. In 2015, he was named one of the 100 most influential people in biotech by Scientific American Worldview.