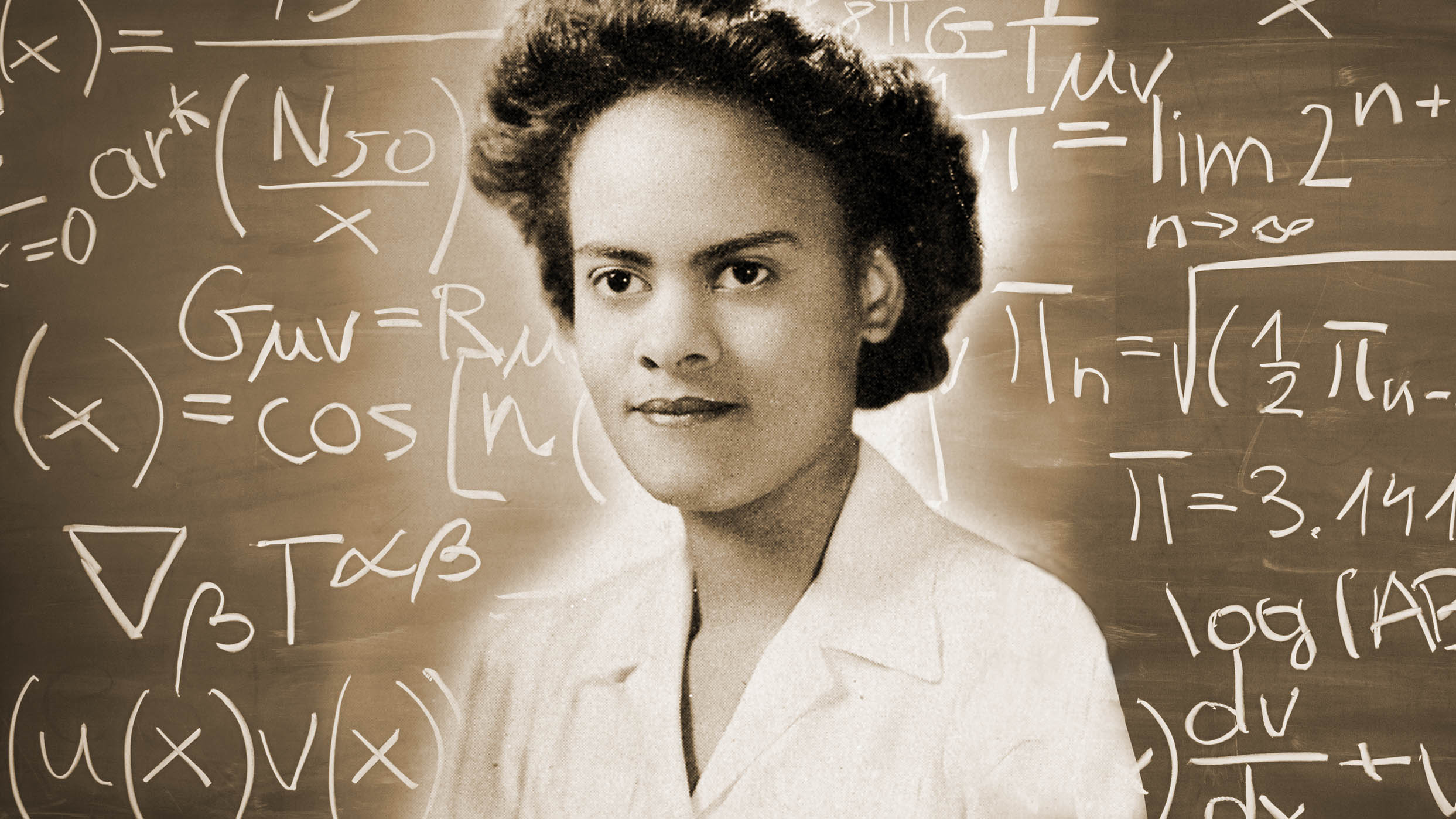

Unsung: Dr. Evelyn Boyd Granville

When I learned that a forthcoming film entitled “Hidden Figures” would focus on the career and remarkable achievements of African-American women mathematicians working for NASA during the Civil Rights Movement, I was absolutely thrilled. The number of movies or documentaries that focus on the intellectual achievements of African Americans working in STEM fields — that is, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — is vanishingly small, despite a wealth of worthy stories to tell. One powerful example is the 2007 PBS documentary “Forgotten Genius,” which examined the life and remarkable career of the eminent African-American chemist, Dr. Percy L. Julian.

“Hidden Figures,” is based on a forthcoming book of the same name by Margot Lee Shetterly, which focuses on the work of Mary Jackson, Sue Wilder, Dorothy Vaughn, Kathyrn Peddrew, Eunice Smith, Barbara Holly and Katherine Johnson — all mathematics pioneers whose work was instrumental to some of the nation’s greatest achievements in space exploration. Just last month, NASA dedicated a new research facility — the Katherine Johnson Computational Facility at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia — to honor the achievements of one of these “human computers.”

Of course, these seven pioneering African-American women are not the only trailblazers in the field of mathematics. Another groundbreaker is Dr. Evelyn Boyd Granville, a mathematician who worked on orbit computations and computer procedures for three space-related projects — Project Vanguard (originally managed by the Naval Research Laboratory and later transferred to NASA); Project Mercury (the nation’s first effort to put a man in space); and the program that eventually put a man on the moon, Project Apollo.

Granville, now 92, is a “Hidden Figure,” too.

Born in Washington, D.C. in May of 1924, Granville was the youngest child of Julia, a homemaker, and William Boyd, a chauffeur. Granville had an older sister, named Doris. After her parents separated, her mother Julia was employed as a currency and stamp examiner at the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Upon graduating from Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., Granville enrolled at Smith College, a private college for women in 1941. As an undergraduate student at Smith College, she was very interested in both the fields of astronomy and mathematics, but decided to pursue the latter as a major. She graduated from Smith College summa cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1945.

“Fortunately for me as I was growing up, I never heard the theory that females aren’t equipped mentally to succeed in mathematics, and my generation did not hear terms such as ‘permanent underclass,’ ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘underprivileged,’” Granville once wrote. “Our parents and teachers preached over and over again that education is the vehicle to a productive life, and through diligent study and application we could succeed at whatever we attempted to do.”

Granville decided to continue her studies and applied for graduate work at both the University of Michigan and Yale University — opting for the latter, which offered her a full scholarship.

Granville was twice awarded the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, and later earned an Atomic Energy Commission Predoctoral Fellowship to complete her graduate work under the direction of Dr. Einar Hille, who was an expert in functional analysis at Yale. In 1949, with a thesis entitled “On Laguerre Series in the Complex Domain,” Granville become the second African-American woman in the nation to earn a doctoral degree in mathematics. (Dr. Euphemia Lofton Haynes, another Smith graduate who earned a PhD in mathematics from Catholic University of America in 1943, was the first, while Dr. Marjorie Lee Browne‘s 1949 PhD in mathematics from the University of Michigan made her the third.)

Granville’s unique opportunity with NASA came in January 1956, when she accepted an appointment at the International Business Machines Corporation, now known as IBM. In subsequent years, she held a variety of staff and consulting positions with the company, but when IBM won a NASA contract, Granville immediately requested to join the space agency’s Vanguard Computing Center in Washington, D.C. That request was granted, and she was instrumental in developing orbital calculations for the nation’s burgeoning efforts to put rockets — and eventually people — into space.

In 1960, Granville moved to Los Angeles with her new husband, Reverend G. Mansfield Collins. The couple divorced in 1967, and she was remarried in 1970 to Edward V. Granville, a real estate broker.

In August 1962, while living in Los Angeles, Granville joined the staff of the North American Aviation Company (NAA) as a Research Specialist. NAA was subsequently awarded a NASA contract for the design of the space vehicle for Project Apollo, and Granville would go on to help ensure that American astronauts would land first — and safely — on the surface of the Moon (and return to Earth). Granville remained on Project Apollo until 1967.

Over the course of her career, Granville held numerous positions in academia, government and industry. She taught mathematics at Fisk University in Nashville, and Texas College in Tyler, Texas — both among the nation’s 107 historically black colleges and universities – as well as California State University, Los Angeles. Granville also worked as a mathematician at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) in Washington, D.C., focusing on calculations for the development of ballistic missiles.

Dr. Granville has a rich legacy focused on teaching and cutting-edge mathematical research — so much so that two of her former students at Fisk University, Dr. Vivienne Malone Mayes and Dr. Etta Z. Falconer, both went on to earn doctoral degrees in mathematics. In addition, she co-authored (with Jason Frand) the textbook, Theory and Applications of Mathematics for Teachers (Wadsworth Publishing Company) in 1975.

For all of this, Granville remains largely unknown to many mainstream Americans, which is why she is one of Undark’s “Unsung” heroes.

“I remember one day my sister said to me, I don’t know where she learned it, ‘did you know you were one of the first black women to get a PhD in math?’ Granville recalled in a lengthy 2014 interview, on the occasion of her 90th birthday. “I said, ‘No, I didn’t know that.’”

“It never occurred to me to be the first,” she added. “I just wanted to major in mathematics.”

Sibrina Collins is an organometallic chemist and former writer and editor for the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. In July, 2016, she will become the first executive director of the Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, Michigan.