Health Disparities: Improving, But Not Enough.

The most recent edition of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ annual report of American health outcomes landed this week, with some interesting, updated analysis on racial health disparities. The news on this front is mixed.

The new report — a robust statistical affair that has been prepared annually and submitted to the president and Congress for nearly four decades — revisits the 1985 Heckler report, a groundbreaking analysis that laid bare gaping health disparities between white Americans and minorities — particularly blacks.

Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services at the time, remarked at the outset of that report that those disparities represented “an affront both to our ideals, and to the ongoing genius of American medicine.”

Thirty years later, the racial and ethnic health gap has narrowed in many areas, but disparities persist.

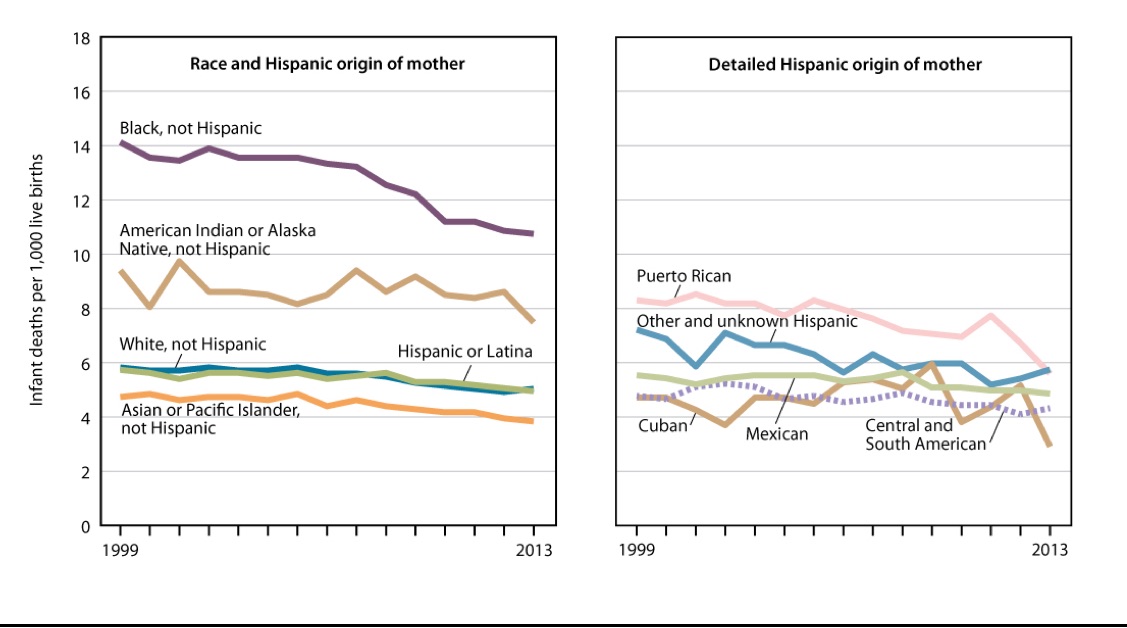

On the upside, infant mortality — one of the key indicators of overall health across large populations — has declined among non-Hispanic blacks, particularly over the last 10 years, though it remains the highest rate among all ethnic groups. The difference between that and the lowest rate of infant mortality has narrowed from just over nine deaths per 1,000 live births in 1999 — the statistical base year used by HHS in this analysis — to about seven.

That’s not great, but it’s still progress:

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, Health, United States, 2014, Figure 19. Data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS).

Other highlights from the Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities:

• Hispanic adults between the ages of 18 and 64 had the highest percentage lacking health insurance (just over 27 percent in the first six months of 2015), while non-Hispanic whites and Asians were neck-and-neck for the lowest rate, with both coming in well under 10 percent. In all instances, it was clear that the Affordable Care Act, for all its flaws, was driving the number of uninsured persons downward.

• At just over 11 percent, non-Hispanic black mothers had the highest percentage of pre-term births — defined as birth prior to 37 weeks of a pregnancy. Non-Hispanic whites and Asians had the lowest percentage of preterm births: 6.9 percent and 6.8 percent, respectively.

• Perhaps most interesting, the analysis noted that the so-called epidemiologic paradox of the Hispanic population in the U.S. continues. “Hispanic individuals are often found to have quite favorable health and mortality patterns in comparison with non-Hispanic white persons and particularly with non-Hispanic black persons,” the authors noted, “despite having a disadvantaged socioeconomic profile.” One example: Hispanic females have the longest life expectancy of all Americans — 84 years at birth. That’s a full 12 years longer than the lowest life expectancy, which is 72 years of age, on average, for black males.

The report suggests that the lingering disparities are a result of a variety of complex factors and, in the aggregate, the gaps between populations on metrics ranging from life expectancy, infant mortality, and cigarette smoking among women, to flu vaccinations among the elderly and health insurance coverage, all appeared to be narrowing. But on some fronts, the gap widened — including for low-risk cesarean sections, flu vaccinations among adults under 64, and inadequate dental care.

“Despite improvements over time in many of the health measures presented in this Special Feature, disparities by race and ethnicity were found in the most recent year for all 10 measures,” the authors noted, “indicating that although progress has been made in the 30 years since the Heckler Report, elimination of disparities in health and access to health care has yet to be achieved.”

The full report, complete with tables and source data, can be found here.