Climate Fiction: Reaching Readers Where Science Can’t

Last week, The Chronicle of Higher Education pointed to the rise of climate fiction in college classrooms, estimating that more than 100 courses now assign the genre. By exploring fictional future worlds devastated by climate change, the thinking goes, students will come to appreciate the gravity of our environmental moment.

And it’s not just students consuming climate fiction: The general public seems to enjoy reading about – and watching – stories of climate cataclysms and biological disaster. In recent years, The Guardian, The Atlantic, and The New York Times have all written about the rise of climate fiction in popular culture.

Can climate fiction raise awareness of potential futures in a way current science can’t?

But how established is the genre, really? A study published earlier this year attempted to provide an answer. The analysis, published in Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, presents a census of the genre’s seminal titles – from Arthur Herzog’s 1977 novel “Heat” to 2014’s “Odds Against Tomorrow” by Nathaniel Rich – suggesting that they are helping to shape both “a canon of climate change fiction” and a new tributary for literary and critical theorists to explore. Citing the 2015 literary criticism book “Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change,” the analysis puts the total number of climate fiction books currently at 150.

Adeline Johns-Putra, a Reader in English Literature at the University of Surrey and author of the new study, extracts two overarching themes that reach across the genre — what she calls “preoccupations with parenthood” and a “dominant tone of lament.” Anyone who has read Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” or Margaret Atwood’s “Oryx and Crake” would agree. Climate fiction is concerned not only with climate change’s “existentialist challenges, but with its emotional and psychological dilemmas,” Johns-Putra concludes. Perhaps it’s by tugging at our heartstrings that the genre has become so successful.

Naomi Oreskes, a historian of science at Harvard University, agrees.

“I think what experience shows us is that various forms of non-fiction don’t reach most people,” Oreskes wrote in an email. “Moreover, non-fiction doesn’t actually get to the heart of the issue — and I mean that literally: Our hearts.” By presenting fictionalized imprints of the future of the planet, she suggested, the genre can cut deeper than non-fiction.

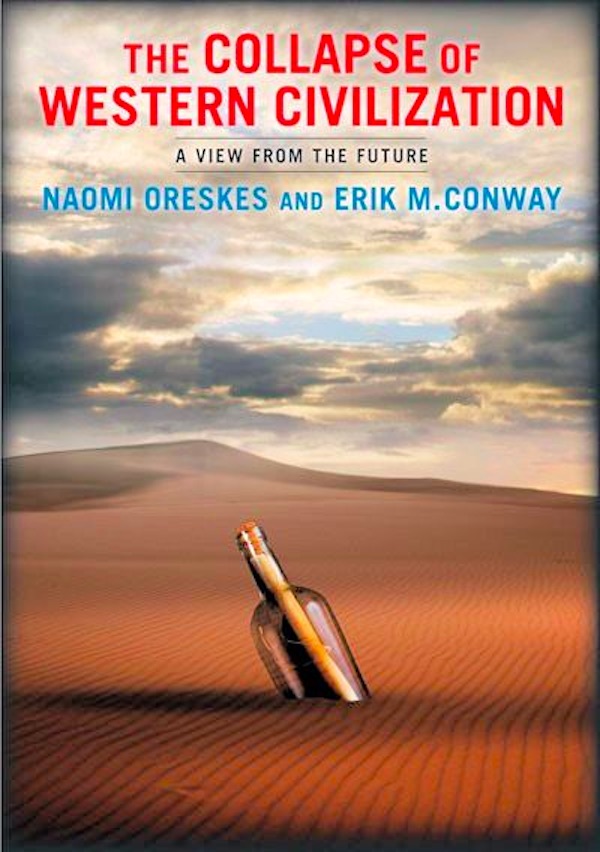

In 2011, Oreskes published “Merchants of Doubt,” a work of non-fiction examining the perversion of science by the oil and tobacco industry. More recently, she tried her hand at co-authoring a climate fiction novel, “The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future.“

“I have no idea who has bought and read ‘Collapse,’” Oreskes said, “but I would venture to guess that many of the readers of that book do not overlap with the readers of ‘Merchants.’”

In that sense, the evolution of climate fiction would seem crucial in the effort to galvanize minds around the scientific realities facing modern civilization. The most detailed PowerPoint presentation or scientific paper, no matter how exhaustively peer-reviewed, cannot communicate the immediacy or devastation that a fictional portrayal of a sunken coastline, an inundated city, or a barren wasteland can impress upon a reader – particularly if scientists are predicting those things as being hundreds of years away.

Or perhaps just decades.

“Despite all the good science that has been published about climate change, most people don’t really understand why it matters,” Oreskes said, “and we especially don’t understand why it matters to us — people living here and now, as opposed to future generations or in faraway places.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Climate fiction, “cli-fi” for short, is a genre born in the 21st century. There is no school of cli-fi, and there is no literary canon. Anything goes, and anyone can write it. This article was a,very good over-view of where the new genre is headed.

I recommend futurist Guy Dauncey’s new book ‘journey to the future’; it gives a good overview of the problems we face today and will likely face in the coming years, set in the year 2032 it goes over the practical solutions we need to start working towards a sustainable human society as he describes a shift towards an ecotopia as a needed change to avert disaster.

Great piece. I’d like to add that not all cli-fi is dystopian and futuristic. I’m an ecologist who has written a present-day mystery. “Cold Blood, Hot Sea” helps readers understand what’s happening right now, including harassment climate scientists must endure.

For reasons of politics or personal safety it is some times necessary

to wrap up unpleasant facts in the form of fiction.This type of writing

also has it’s risks. Unwanted groups of conspiracy theorists

may coalesce around writers or stories.

I’d recommend Michael Crichton’s “State Of Fear” as a great place to start