Race, Science, and the Continuing Education of Razib Khan

On March 18, 2015, The New York Times announced that Razib Khan would become a contributing opinion writer. A day later, The Times terminated the contract.

At the time, Khan was a Ph.D. student in genetics at the University of California, Davis and a popular science blogger. He had written about science for The Times, Slate, The Guardian, and other mainstream publications. For years, Discover had hosted his genetics blog. The famed Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker had even called him “an insightful commentator on all things genetic.”

“I have been made aware that Breitbart News has used photos of me … in an article about [the] ‘alt-right,'” Razib Khan wrote on Twitter last year. “To be clear, I’m not “alt-right.'”

Khan had also spent more than a decade hanging around the white nationalist fringe. When The Times hired him, he was blogging at The Unz Review, an “alternative media selection” that would soon emerge as a platform for the alt-right, the loose movement of white nationalists and right-wing extremists that has come to new prominence with the presidency of Donald J. Trump. Khan’s fellow science blogger at The Unz Review was Steve Sailer, a right-wing journalist and the author of a biography of Barack Obama titled “America’s Half-Blood Prince.”

Fragments from that part of Khan’s life started circulating online almost immediately after the news of his appointment at The Times was announced. Those fragments included a letter he had written in 2000 to VDare, a white-nationalist website, suggesting among other things that black people are innately less intelligent than white people. Later that week, a spokeswoman for The Times issued a statement saying “after reviewing the full body of Razib Khan’s work, we are no longer comfortable using him as a regular, periodic contributor.”

Almost two years later, the alt-right and its obsessions with race are ascendant — and scientific arguments are central to the movement’s ideological claims. Not surprisingly, Khan’s story has stuck around. Two prominent writers for Breitbart, the alt-right news outlet whose former executive chairman, Stephen Bannon, now serves as chief strategist in Trump’s White House, mentioned Khan sympathetically in a widely-read manifesto published last spring. Those writers — Milo Yiannopoulos, who resigned from Breitbart last week, and Allum Bokhari — lamented that Khan had “lost an opportunity at The New York Times over his views on human biodiversity.”

Yiannopoulos, who has been banned from Twitter for inciting harassment, and who was shouted down by protesting students before a scheduled appearance at UC Davis last month, has since used Khan’s story in his public speeches.

For all of this, dismissing Khan as a crank would be a mistake. While his associations are extremist, his science is not, and very little of what he writes about human genetics falls outside the pale of ordinary scientific discourse. Khan is also not alone in bridging the worlds of scientific racism and mainstream science and science writing. The Times dropped Khan in 2015, less than a year after one of its own science journalists, Nicholas Wade, published a book that made more sustained, incendiary arguments about race, with far more blowback from scientists.

Still, Khan’s career exemplifies the sometimes-murky line between mainstream science and scientific racism, and it illustrates how difficult it can be to define the boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable speech about race — and to understand what, if anything, science has to do with it.

This issue isn’t going away. Researchers are getting better at quantifying minute differences among individuals and among groups, and their findings will almost certainly be used, as they have long been, by people willing to ascribe a sort of racial destiny to all manner of human virtues and faults. Most scientists will object to this application of their work, but the illiberal challenges to scientific scholarship, perhaps now more than ever, seem destined to come not just from creationists and neo-skinheads, but from self-styled hyper-rationalists, too — from people who adhere to what they consider a “science-first” worldview, who often ignore history and social context, and who are predisposed to drawing troubling, and sometimes patently racist conclusions based on otherwise dispassionate science.

In other words, they’ll come from people who sound a lot like Razib Khan.

Seventeen years ago, when scientists announced the first full sequencing of the human genome, it was heralded as a breakthrough that would quash scientific racism. At a White House press conference, Craig Venter, the head of Celera Genomics, announced that one goal of the work was “to help illustrate that the concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis.” In the five genomes they sequenced, Venter said, “there is no way to tell one ethnicity from the other.”

Scientific racists — people who argue that their ideas about racial hierarchies are rooted in biological facts about human difference — have been peddling their ideas for more than a century. But Venter and others were betting that the sequencing of the human genome would show that race is mostly a social construct.

This idea is easy to caricature. Everyone recognizes that human traits, like height and skin color, are variable. But the particular way we choose to sort people into buckets based on that variation is far more arbitrary — and largely unscientific. “We just have to understand that these categories are ones that human beings make,” said Ann Morning, a sociologist at New York University who studies racial classification. “They are not rules which are handed down to us by Mother Nature. In that sense, racial categories are like astrological categories: These are both systems for classifying people to help make sense of why they act the way they do.”

In fact, from a genes-eye point of view, racial groupings don’t make much sense at all. People from different regions in Africa can be as genetically distant from each other as a Greek is from an ethnic Korean. People who are considered black in the United States may get the majority of their genetic material from Europe.

Personal genetics provides a good way to map human similarities. But it also provides new opportunities to quantify human difference. Today, white nationalists buy 23andMe tests to prove their whiteness. Alt-right thinkers argue that genetics shows that racial differences do have a biological basis. Scientific racists look for evidence that there are deep, innate differences between racial groups, especially with respect to intelligence.

“Behind every racist joke is a scientific fact,” Milo Yiannopoulos told Bloomberg last year. Richard Spencer, the young neo-Nazi who coined the term “alt-right” — and who became famous recently for receiving an enthusiastic punch to the head in a video that quickly went viral — publishes a journal that often includes articles about human evolution and genetics. Steve Sailer has also helped rebrand scientific racism as “human biodiversity.”

“The entire Alt Right is united in contempt for the idea that race is only a ‘social construct,’” the Yale-educated white nationalist Jared Taylor wrote last fall. “Race is a biological fact.”

Few writers have moved more comfortably between the worlds of mainstream science writing and the alt-right than Razib Khan. A fast-talking autodidact with right-wing political views, Khan writes about everything from foreign policy to CRISPR. A recurring theme of his work is that racial differences are real, and that they have a biological underpinning — that they’re both social constructs and biological truths.

Khan was raised by Bangladeshi immigrants in eastern Oregon, “an atheist brown kid in a highly religious, conservative, Republican area,” as he puts it now. In the late 1990s, he started exploring the nascent right-wing blogosphere. Around 2000, he joined a private email discussion group about human biodiversity organized by Sailer. (More mainstream academics, including Steven Pinker, were also in the group).

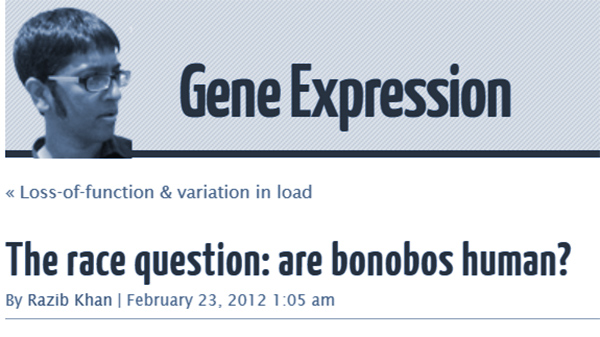

Not long after that, Khan helped a geneticist friend start a blog about science. They called it Gene Expression — GNXP, for short. Its writers discussed technical topics, as well as issues with a more political edge, like gender and racial differences.

A few years later, Khan went on the payroll of Ron Unz, a libertarian who ran for governor of California in 1994. Unz, who made a fortune in software development, offered Khan something that Unz describes as “a sort of fellowship or junior fellowship” to further his scientific career. Both Khan and Unz are vague about the reasons for the fellowship, but the gift was contingent on Khan leaving his job in software to focus on a scientific career. It was a big part of why he got on a graduate school track and ended up at UC Davis.

Unz’s grants reflect the diversity of his interests, which include Israel, non-interventionist foreign policy, and human evolution. In 2009, for example, according to Unz Foundation tax documents, Unz gave $24,000 to Sailer; $500,000 to the University of Utah evolutionary anthropologist Gregory Cochran, known for his controversial research on recent human evolution and Ashkenazi Jewish intelligence; and $108,000 to Khan, to be paid out over three years.

Unz was not Khan’s only link to the emerging alt-right fringe. In 2009, Khan spent a year blogging for Taki’s Magazine, a white-supremacist site, at the invitation of Richard Spencer. There, Khan wrote posts about everything from genes to Freud to Jewish intelligence. In one back-and-forth, he and Spencer analyzed the resemblance between Jews and the Vulcans in Star Trek.

This fall Spencer made national news after he organized a rally in Washington, D.C. that featured Hitler salutes and cries of “Hail Trump!” But Spencer “was not a white nationalist then,” Khan told me. (Recent reporting on Spencer documents him pivoting toward open support for white nationalism around the beginning of 2009, the same time that Khan joined Taki’s.)

At Discover Magazine, Khan once wondered why African bushmen are considered human, but bonobos are not.

Meanwhile, Khan’s mainstream science writing career was flourishing. He moved GNXP to ScienceBlogs, and then, in 2010, to the website of the very mainstream Discover Magazine. There, he wrote long posts about why race was biologically real. In one, he asked why African Bushmen are classified as human, and bonobos are not. In another post, he linked his science to his politics using language that’s reminiscent of white nationalist arguments: “The ultimate root of my conservatism is a fact, not a value,” Khan wrote. “That fact is that human cognitive and behavioral variation is real and important. We are not uniform.”

(“I don’t agree with that anymore, I guess,” Khan told me more recently.)

When Unz started his own site in 2013, Khan signed on as his first writer. Soon, a rotating cast of bloggers joined him. While he was at The Unz Review, Khan continued with his genetics program at UC, Davis (he recently went on leave to join a biotech startup in Austin), wrote op-eds for The New York Times, and co-authored a piece for USA Today arguing that race is biologically real.

The way Khan tells the story, he was caught off guard by the sudden rise of the alt-right, and by the extremist turn of Unz’s website. The day before I contacted him to request an interview, Khan announced that he was leaving The Unz Review. His new standalone blog, still called Gene Expression, launched in January. Over the phone, he told me that the move was partly because he wanted to be an independent blogger again, and partly because he had grown uncomfortable with some of the material on Unz’s site. He framed the issue as an image problem, not a moral one. “I wasn’t comfortable with some of the co-branding,” he said.

Hadn’t Sailer and other Unz contributors been writing things like this for years? Khan said that he used to be more tolerant of those perspectives. “Obviously, I don’t condone it,” he said. When I observed that standing by silently — and even linking to Sailer’s work — seemed like the definition of “condone,” Khan hesitated. “In terms of being at Unz, I was probably there too long,” he said.

Still, Khan insisted that his writing about the biology of race was sound. “It’s not socially acceptable to say that there might be group differences in an endophenotype — in their behavior, intelligence, anything that might have any genetic component,” Khan said. “You cannot say that, okay? If someone’s going to ask me, I’m going say, ‘It could be true.’”

Other scientists, he insisted, believe the same things. They just won’t admit it. “I’m sick of being the only fucking person that says anything,” said Khan. “I know I make people uncomfortable, but a lot of times I say what they’re thinking.”

Many prominent geneticists familiar with Khan’s work do take him seriously. “I don’t agree with everything that Razib writes, but I think that he does write about population genetics very clearly,” said Graham Coop, a population geneticist at UC Davis who serves on Khan’s dissertation committee, and who has taken a high-profile stance against scientific racism.

Michael Eisen, a biologist at UC Berkeley, described Khan as “a very, very bright geneticist” who “understands modern human population genetics as well as almost anybody.” Eisen disagrees with many of Khan’s conclusions, and he said that Khan had “allied himself, in one way or another, with people whose views are not just repugnant — they’re just wrong.” But, Eisen added, “I think many of the things Razib writes highlight the implications of modern genetic research in ways that people find upsetting, but aren’t necessarily wrong.”

What does this say about the post-racial genetics that Craig Venter imagined nearly two decades ago?

It depends on how you parse it. Sarah Tishkoff, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania, helped write a 2016 Science paper recommending that researchers stop using the concept of race in human genetics research. Still, she told me, population clusters exist. “We can see that there are differences,” Tishkoff said. “But then you have to ask the question, ‘What do those differences mean? Do they correlate with so-called racial classifications?’ No, actually they don’t.”

Joseph Graves, Jr., an evolutionary biologist who writes about the biology of race, was more skeptical about clustering. Instead of distinct human groups, he said, one population grades into another, forming continua called “clines.” “There’s no unambiguous way to cluster individuals and say where one cluster begins and another one ends. It’s dependent upon the dataset you have. It’s dependent upon the genetic markers you look at. But the best models of human population show that we’re a continuous cline.”

Eisen made a similar point about the difficulty of making categories. But he cautioned against saying that everything is clines. “It also is not true that we’re a uniformly mixing population.”

The bigger question, of course, is why any of this matters to these scientists. Here’s one potential reason: Geneticists will soon get much better at understanding how genes contribute to complex, elusive traits like intelligence. Inevitably, some people will try to connect the dots and show that the genes influencing a trait like intelligence differ between these population groups.

Khan is blunt about those implications. “Honestly, I would just sit on my hands for now,” Khan recently responded to a GNXP commenter who was curious about the relationship between race and IQ. “In the next < 5 years,” he wrote, “the genomic components of traits like intelligence will finally be characterized.”

Simply pondering such issues will strike many people as racist. Asking a question, even skeptically, can offer an implicit endorsement of its premises. But while it’s possible to fire Khan from The Times or act as if the alt-right is a marginal movement, these questions are not necessarily fringe. And there’s no agreement about when, if ever, it is appropriate to ask them.

Little illustrates those inconsistencies better than the case of Nicholas Wade, who was working at The Times as a science reporter when Khan was hired, and then dropped, from the op-ed page.

Wade’s 2014 book, “A Troublesome Inheritance,” marshals genetic evidence to argue that racial differences are real and have deep biological roots. Then Wade argues that these differences explain global disparities, such as why Haiti is more impoverished than Iceland, or why political structures in Europe are different than those in East Asia — where, Wade argues, people are genetically predisposed to be more docile.

Coop, of UC Davis, helped gather more than one hundred biologists to sign a letter to The Times denouncing the book. Even Khan described it as “not a very good book.” Graves told me that Wade is a “die-hard racist.”

After The Times dropped Khan, Eisen went on Twitter to point out the contradiction. “The thing that galled me in particular, and that led to that tweet, is they’ve been giving large amounts of print space to Nicholas Wade, who is unambiguously and unintelligently a racist in his writing,” Eisen told me. “Wade has been pushing these basically sort of facile, eugenicist views of the world for 20 years.”

“A Troublesome Inheritance” remains very popular on the alt-right, and Wade has done little to discourage this. After the book came out, he did a long, warm podcast interview with white nationalist Taylor.

“I can’t control how people use the book,” said Wade, who retired from The Times last year but still regularly contributes freelance articles to its science section — and who was himself interviewed by Khan back in 2010. Wade insisted that the book was not racist, but in an phone call, he also did not take an opportunity to disavow the white nationalists who have embraced it. He was dismissive of the controversy that surrounded “A Troublesome Inheritance,” and of the biologists’ letter to The Times. “It was an attempt to suppress a discussion of race,” Wade said. “Almost everything in the book you can find in The New York Times in my articles, and none of these guys objected at the time.”

It is true that many of the ideas expressed in the book are not exactly new. Other books — most notably “The Bell Curve,” a 1994 bestseller that infamously argued that black people are innately less intelligent than white people — have argued that racial groups are real, that there are substantial behavioral differences among them, and that those differences may explain political realities. And sociological studies of the public suggest that white Americans are likelier to ascribe a genetic cause to the behavior of black people than they are of white people.

Does that mean that uncomfortable scientific findings should be censored? Wade, Khan, and others often argue that their voices are suppressed by a politically correct academic left. In one recent Unz Review post about an academic who received blowback for speculating about racial difference, Khan wrote that “the extremely vehement reactions on this topic reveal an aspect of how ideas are policed in our society.”

I ran that notion by Graves, who in 1988 was the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. Graves studies the evolution of aging, but, after the publication of “The Bell Curve,” he started writing about race, too. “I went through an educational system, from kindergarten through my Ph.D., that was profoundly racist and that threw roadblocks against my progression at every step of my career. I had no desire to start writing about racism in genetics and evolution. That wasn’t my interest. But I couldn’t avoid it, because those theories were being directed against me, against my family, against my friends,” Graves said.

When I showed Graves the passage about policing ideas, he sounded incredulous at the thought that these such views were being suppressed. “I don’t know what society he lives in,” Graves said. “In the societies I’ve lived in, racism has been the norm.”

A few years ago, Jacob Tennessen, an evolutionary geneticist at Oregon State University, joined Twitter. He expected to deal with creationists. Instead, he says, the aggressive pseudoscience came from racists — and, specifically, people within the human biodiversity movement, who kept arguing that traits like intelligence had clearly been subject to recent, sharp evolutionary shifts that left some racial groups smarter than others.

The people he encounters online are “pro-science and pro-evolution, but what they’re doing is not science at all,” Tennessen told me. “It’s a really dangerous pseudoscience.”

For all the attention that creationists receive, Tennessen’s kind of experience may be more typical — and more important. How, though, should geneticists respond to people who draw racist conclusions from their work? That question is only going to become more pressing. Genes continue to play an outsize role in popular understandings of human nature. Personal genetic testing services are making discussions about ancestry, race, and genes more accessible — and more commercialized — than ever before. And the internet is lending a platform to a whole new generation of tech-savvy scientific racists.

Faced with that challenge, Khan may be a textbook example of what geneticists should not do: namely, focus on the science alone, and act as if the context doesn’t matter. “The science is always prior to everything else,” Khan told me. “Everything else is just commentary. If the commentary comes before science, that’s a problem, but that’s how a lot of discourse works. I understand. I’m not trying to be naive about it. But the reality is that’s not how I work.”

Can science be severed quite so easily from politics? Khan’s own story, which includes financial and ideological entanglements with the alt-right, seems like evidence that it cannot. The belief in perfect hyper-rationality, divorced from any kind of bias or preconception, can be its own kind of political fantasy.

For better or for worse, science does have a way of working itself into political ideologies, just as political ideologies can shape the choices that scientists and others make. Historically, that’s often been the case with the study of race. Morning, the NYU sociologist, points out that new generations using new technologies often seem to circle back to old prejudices.

“There’s a long history in the West of trying to use biological data to claim that there are such things as a handful of discrete races,” she said. But “whether the ostensibly impartial data are blood types, like they would have been a century ago, or genes today, or skull sizes,” the results are familiar: “It’s always about reproducing the same hierarchy.”

Michael Schulson is an American freelance writer and an associate editor at Religion Dispatches magazine, where he helps produce The Cubit, a section covering science, religion, technology, and ethics.

CORRECTION: This piece has been updated to correct a description of Graham Coop. Coop is on Razib Khan’s dissertation committee, but is not his adviser.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Just stumbled upon this. You’ve let Razib off awful lightly. If he’s good in his field, it’d be good as a bench jockey sort of good. His grasp of basic argumentative logic is not what it ought to be, he’s not particularly clever outside of field of study, I’m dubious that that’s so different inside it. If you start digging through old gnxp stuff, you’ll find the blog was pretty noxious. Godless Capitalist, or gp, co-founder of the blog, is more or less a Nazi. Razib was being groomed for bigger things (like the NYT) so he usually kept it at least pseudo-scientific. But it was pretty clear where his sympathies lay. His huge motivator is the deep desire to see African declared intellectually and morally inferior to whites and Asians. That’s the deep and not-at-all-secret desire that colors everything he says and writes. So regardless of what the science ends up saying, who wants someone who longs for this outcome around? Anywhere where his judgment might come into play?

Racist pseudo-scientists should simply validate their claims with the genetic evidence. Otherwise they should shut-up. But if the evidence confirms that Africans have the best genes for intelligence, will they accept that finding or will they reject it and double down on their pseudoscience?

> Can science be severed quite so easily from politics? Khan’s own story, which includes financial and ideological entanglements with the alt-right, seems like evidence that it cannot. The belief in perfect hyper-rationality, divorced from any kind of bias or preconception, can be its own kind of political fantasy.

Maybe if politically/ideologically neutral organizations were open to funding research into such scientific inquiries, i.e. the genetics of intelligence, behavioral, psychological traits, etc., then people interested first and foremost in the science (ex. Razib Khan) wouldn’t have to rely on grants from the likes of Unz. Note that this criteria automatically rules out the current incarnation of Academia, which has been well documented by people like Jonathan Haidt to possess an overwhelming leftist bias.

http://archive.is/LSV8c

Razib’s tweet: “also kill all white people. cancer humans as I like to call them”

Charming guy.

Razib Khan is basically a rude, semi-literate (just look at his atrocious spelling & grammar in his blog comments), pretentious, cowardly ignoramus. Many of his “arguments” are just a joke. I tried “debating” that simpleton several times in his very own blog, specially regarding certain historical points, and when he starts to figure out he is getting beaten left & right by those who are better acquainted with a given subject, the dishonest chump simply censors your posts and starts flinging rude comments at his opponents and does not give them the opportunity to answer back (many times he just closes the thread so nobody can respond.) Ridiculous clown.

The left isn’t obsessed with race? Especially black Americans? Get out of here.

Everyone can see it. Black Americans are not even the largest minority group yet they are all over liberal/democrat magazines, newspapers, television, radio, and websites. Where are the hispanics they are the largest minority group. The left isn’t obsessed with them the way they are black Americans and to a slightly lesser extent Africans.

What about the liberals favorite news channel CNN? With their blatant casting formulas based on color. CNN obviously was knee deep in colorism with regards to black Americans. It’s obvious that their liberal viewers have a fetish for black Americans who they deem as looking non-African and having “light” skin.

What about the liberal abortion doctor who said he was doing a good service by getting rid of ugly black babies. How sick can you get.

What about the progressives history with eugenics?

You liberal/democrat devils need to clean up your own filthy outhouse before you go attacking others.

Want a narrative that would destroy the alt-right and impose an inferiority complex on masses of them?

“Modern racial classifications are not very useful in describing societal behavior.”

This may backfire in that it’s similar to the type of thinking that led to hitler and imperial japan. But, this type of thinking, true or not, is already prevalent outside of multicultural areas. It leads/lead to violence in some areas like Africa, Europe, East Asia, and Turkey. In others, like India, it leads to federalism. But, considering the far more multicultural and geographically mixed country we live in, it could be a useful and low-risk narrative that prevents white nationalists from gaining too much power, if it’s promoted at the right level and in the right style.

It’s important to point out is that many white nationalists are actually largely aware of this complex reality and are actively fighting against it while pushing a broad, simplistic, ill-defined “white nationalist” agenda in its place that protects their fragile egos. If you investigate stormfront, you’ll see how butthurt members get when differences between white nationalities are pointed out. The alt-right is already at a fracturing point and this narrative would break it apart.

The comments show why something like this would have to be censored, even if true. Millions of people would love an excuse to be able to dislike people who look different, and perhaps dozens would be able to view the situation with any nuance. This would pretty clearly lead to some new hateful apartheid. Wish the world were as rational as some purely scientific people want it to be, but humans are stupid and systems are stupider.

The assertion that Razib “often ignore[s] history and social context” is risible to anyone who’s familiar with the extraordinarily long and detailed posts he frequently writes on historical topics. The man clearly has a deep knowledge of history, and I can only believe that the contrary claim in this article is due to ignorance or malice.

That is of course only one problem with this transparent hitjob attempt, so it’s encouraging to see the wide range of comments attacking its *other* flaws.

So am I to understand that “diversity” is a scam? That there are no inherent substantive differences between demographic groups?

When the affirmative action zealots suggest there are differences based on demographic differences they are being benevolent.

When HBD zealots suggest there are differences based on demographic differences they are being bigots.

Please explain the difference.

Joseph Graves’ quotes purporting to address “Bell Curve” miss the mark. His “clines” bit is to an extent an elaborate straw man argument. No one claimed that races are completely crisp, so proving that there are overlaps and smearing and such does nothing substantial to the underlying claim.

As to this bit:

>>> When I showed Graves the passage about policing ideas, he sounded incredulous at the thought that these such views were being suppressed. “I don’t know what society he lives in,” Graves said. “In the societies I’ve lived in, racism has been the norm.” <<<

Here Graves is being deceptive. The claim was not about the existence of racism. The claim was about the existence of "idea policing" in academia, in the Cathedral.

The article makes it sound, as have many others, that The Bell Curve was primarily about racial differences in IQ. I doubt that the author read the book. The book is consistent with mainstream intelligence research, as indicated by the many researchers who attached their names to a statement published in the Wall Street Journal. The mainstream media do not even send correspondents to the major conferences of intelligence researchers, yet most commentators and bloggers who write about IQ are primarily influenced by what appears in the media. In the most recent survey of intelligence researchers, respondents were more likely to say that Steve Sailer accurately reflects their work than the New York Times, National Public Radio, or The Economist.

When asked to recite a series of digits in reverse order, ethnic sub-Saharans are not, on average, able to recite as long a series as ethnic Europeans or Latinos.

When presented with very simple mental tasks, the average response time among blacks is slower than that among ethnic East Asians or ethnic Europeans.

Blacks have, on average, less cranial capacity than ethnic East Asians or ethnic Europeans.

Big Brother would be doubleplus proud of this doublepluslygoodwrited piece. Bravo.

If SCIENCE finds that RACISM = TRUTH, then is there some BEAUTY in RACISM???

RACISM is the belief that significant differences in mental and physical traits (other than trivial differences such as facial features, skin color, hair texture etc.) are due to innate genetic differences.

-So if a person believes that on average Blacks of west African ancestry tend to be significantly faster sprinters than Whites due to genetic differences, then that person is RACIST.

-So if a person believes that on average Whites tend to be significantly more intelligent than Blacks due to genetic differences, then that person is RACIST.

Abundant empirical evidence has shown that statistically speaking Blacks tend to be significantly faster sprinters (e.g. Blacks dominate in Olympic sprinting and speed positions in soccer, football, and basketball) and significantly less intelligent (i.e. lower IQ scores and lower on virtually all other cognitively challenging tests) than Whites. If SCIENCE determines that these observed racial differences in traits such as sprinting ability and cognitive ability are in large part due to genetic differences, then SCIENCE will have proven that RACISM = TRUTH. According to Plato and the Western philosophical tradition, the TRUTH possesses BEAUTY and people should believe in TRUTH.

The wide world of common observable empirical facts, and the results of many decades of psychometric testing, is quite consistent with the notion that Blacks are less intelligent than Whites due to genetic differences. For example, there are various traits and health conditions that are known to be genetically associated with intelligence:

-Due to a genetic association, higher IQ people tend to have a higher incidence of myopia (nearsightedness). Compared to Blacks, Whites have a two fold higher incidence of myopia.

-Due to a genetic association, lower IQ people tend to have a higher incidence of schizophrenia. Compared to Whites, Blacks have a three fold higher incidence of schizophrenia.

-Due to a genetic association, higher IQ people tend to have larger brains. Compared to Blacks, Whites have brains that are about 100 ml larger on average.

-Due to a genetic association, lower IQ people tend to have a higher incidence of fatal cardiovascular disease. Compared to Whites, Blacks have much higher incidence of cardiovascular deaths.

Very interesting article, and many good comments. “Race” and “racism” are terrible words, they have profound impacts on people and yet their definitions are so fuzzy and vague (now, and especially across time). And even though the words are awful, they are are linked up with actual real-world phenomena involving skin color, ancestry, etc. that involves a lot of suffering and waste. So the phenomena need to be talked about, dealt with, but the vocabulary we have to work with is poisionous and not clear.

I’m also interested in the psychological aspect that is going on in the nature/nurture battles. Anyone with an ounce of education and experience and commonsense knows that both are very important to anything we care about. Yet some people react strongly to any promotion or demotion of one side or the other – they know both are crucial but the fact is they really care about and are attracted to one side or the other. What is that all about?

I’ve read the article and comments, and haven’t found anyone addressing the question: why is IQ still being used and touted as a measure of intelligence? The IQ test was invented in the early 20th century to filter out “undesirables” (at the time, mostly new immigrant groups like Jews and Italians) from Ivy League colleges. It has been demonstrated repeatedly that IQ tests are socially and culturally skewed, especially as the questions on “general information” tend to focus on what elite groups know. Not only that, but it’s been shown that IQ can vary with age, so that the same child can test very differently at different ages. This focus on IQ as an intelligence measure invalidates all claims about race-based intelligence. As for the so-called Ashkenazi advantage, I’d invite people to look into the ways in which Ashkenazi kids aren’t doing as well these days compared to kids from Asia, or of Asian heritage. Some researchers are suggesting that part of the advantage is more about populations that are striving to succeed in new locations, and are competing heavily for their children to join the elite classes. Cultures that set high expectations for their children, and who encourage them and value learning, tend to produce kids who do better in school. I’d invite readers to look at this piece on the topic from the NY Times, from 2015: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/opinion/sunday/the-asian-advantage.html

IQ predicts things. If a man has an IQ of 80, you immediately have a rough idea of what things he can do, and what things he can’t. This is useful.

Is it a perfect 1:1 measure of intelligence? No. A certain part of a person’s IQ score will be affected by the test design, as well as random noise. But so what? Tools can be suboptimal while still being useful. I have a 23mm socket wrench for my car. It tightens up lug nuts pretty well. Bet you that if I measured it with an electron microscope, it wouldn’t be exactly 23.0000000 millimeters.

The people who complain about IQ never bother to suggest a better method of testing intelligence, so I guess we’re stuck with it.

historian dude – you are so far off the mark here – it’s like you read one NY Times article & ignored over 100 years of consistently replicatible peer reviewed psychometric research. general mental ability (“g”) – more or less “IQ” (but not quite) – is highly stable across the lifespan – consistently predicts, explains many important outcome variables (like longevity, education, law-abidingness, income, etc.) & does it in a way that predicts equally accurately for different groups (yes, that is looked at in EVERY technical manual of any ability test). developing tests & collecting standardization samples is not done haphazardly (it’s the opposite – it’s the one thing psychology does that is actually science – measurement!) but of course a random commenter thought of something that has never been investigated before by any ability researcher in the last 100 years. there is major consensus in the field, but you’d never know it from the NY Times (or any media). huh. wonder why?

A global change on this article changing the terms ‘racism’ (7 hits) and ‘racist’ (12 hits) to ‘non adherent of blank slate dogma’ would make this article parse a tad more reasonably.

Sarah Tishkoff, who says in this article: “We can see that there are differences,” Tishkoff said. “But then you have to ask the question, ‘What do those differences mean? Do they correlate with so-called racial classifications?’ No, actually they don’t.”

Well, here is a paper she coauthored that says this:

“The emerging picture is that populations do, generally, cluster by broad geographic regions that correspond with common racial classification (Africa, Europe, Asia, Oceania, Americas).”

http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v36/n11s/full/ng1438.html

” ‘races’ are neither homogeneous nor distinct for most genetic variation. ” from the same conclusion

population is not race.

@ Gerardo,

Actually, population is often used to refer to the same concept as race. You’re talking about groups of humans that share geographic ancestry.

Generally a good article.

I like Razib, and I’ve learned a lot from him. I also mistrust his new “I reject the alt right” PR angle. When interviewing someone, remember you’re not interviewing the actual person, you’re interviewing a socially-acceptable persona, giving socially acceptable answers. You got one set of answers to your questions. Razib probably has an entirely different set that he gives to close friends. And probably there’s a different set entirely, which are his true beliefs.

Put more bluntly, I don’t believe that Razib truly disavows anything he’s said or done since 2008 or so. I think he’s a man who’s suffered a ton of professional damage by running in certain circles, and is now trying stop the bleeding.

Understandable? Yes, of course. He has a family to support, and he’s no longer on Unz’s teat. I’d do the same in his position. But I still think he’s lying.

Wait until he’s financially secure, ten or twenty years hence. Then we’ll see what he really thinks.

Khan is sitting pat because, as he says, he expects a complete catalog of the genes influencing intelligence with 5 years. At that point, it is simply a question of seeing whether those gene’s frequency cluster with populations. At that point, you either accept the chips as they fall or turn to some kind creation science defense. [There was a paper recently published looking at a set of genes that predicted educational attainment in life by 10%, and we are only at the beginning.]

BTW, Murray didn’t “argue” about racial differences in mean measurements of IQ, he just recited what approximately 100 years of data shows. There can be no rational debate among empirically-minded people about racial difference in IQ scores, the question is to what extent it is environmental, and what extent it is heredity. If its not 100% environmental, then there is a genetic component. Twins studies suggest that IQ is highly heritable, ergo, every reason to sit pat.

This was what the WSJ published in response to the Bell Curve:

http://www.intelligence.martinsewell.com/Gottfredson1997.pdf

The problem the press has is that when it constantly pretends that well documented empirical facts are “arguments”, is it makes it sound like the press and not Charles Murray and Razib Khan are the ones full of BS.

The interesting question that no one is asking is that modern liberalism grew up in a ideological framework based on people like Skinner and Boas who believed in a Blank Slate. As Pinker has noted, most behavioral components of personality (including IQ) are highly heritable. In fact, most of egalitarian ideology assumes a blank slate HAS to be true. So what happens to modern liberalism if it turns out not only the blank slate is false, but that there are significant and different genetic potentials between populations of humans?

What troubles me is the capacity of the ideological system to adapt. There is too much capital invested in medical applications and other applications of genetics to shut it down, so the “creation science”approach will ultimately not work, even if the Anthropologists try it. Pinker has clearly done a lot of thinking on this subject, but he is pretty much alone.

” There can be no rational debate among empirically-minded people about racial difference in IQ scores, the question is to what extent it is environmental, and what extent it is heredity. If its not 100% environmental, then there is a genetic component”

This is absolutely moronic “logic”. Think about it: you’re already starting with an assumption that there is no way the genetic difference could go in the other direction of the phenotypic difference. Just shows how biased and clueless you are. Have you read even the most basic criticisms of the Bell Curve’s discussion of race, you would not have written this.

I’ve found that people who try to argue for for a major genetic component to every supposed racial difference usually know very, very little about race and even less about intelligence.

Srlys:

I guess I don’t understand your comment. No where did I argue in favor of a genetic explanation of group differences in IQ, so I don’t know how a “non-argument” can fail.

Moreover, even if X and Y differ due to genetics, one can not infer that the difference between a set of things containing X and a set of things containing Y differ due to genetics. . . if that is your point? Or is it that the interaction between genes and environment is a complex one, and that the same gene might bear different expressions in different environments? [Epigenetics?]

So a strict environment/genetic break is like a modeling a physical system with a body in motion moved by the Earth’s gravity on a friction-less plane? Like, Newton is bunk because frictionless planes don’t exist, and the world contains multiple bodies, and no one has worked out an analytical solution to the multibody problem where n = the totality of physical bodies contained in the universe. Yeah, you got me! I’ll never be able to aim the artillery cannon at the right angle to hit the rampart!

The debate comes down to Ockham’s Razor vs. socialist politics. But the simplest explanation is not necessarily correct, anymore than the ideologically driven one is necessarily wrong. But it means the socialists have another problem on the scientific front, and they don’t have Stalin and Lysenko to bail them out this time.

One hundred years of testing data is not an “argument” about IQ, any more than 100 years of meteorological data is an “argument” about climate. Nor does 100 years of meteorological data “prove” the cause of a particular climate. However, the media would not portray someone who believes in man-made climate change as making an “argument” that climate exists, or pretend the concept of “climate” itself was in question. Should we reject global warming on the basis that climate zones are arbitrary and culturally constructed, and therefore tell us nothing about physical reality? Isn’t the task of dividing the world up into climate zones just as arbitrary as dividing the world’s people up on the basis of common ancestry? Maybe Exxon-Mobile should get into the cultural construction business too!

There is no reason to argue with someone and get called names when in all probability, within 5 years we will know the answer. It will be interesting if the “pseudoscientists” turn out to be right. Almost as pleasurable as the revelation that Stephen Jay Gould and not Galton was the actual fraud!

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-folly-fools/201210/fraud-in-the-imputation-fraud

The question is, why does one side commit academic fraud (Gould), actively distort results and findings (Tishkoff), and actively exert political power to suppress research programs (American Anthropology Association) into these questions, if they were confident that the empirical evidence ultimately supports their side against the “pseudo-scientists”?

Srlys:

You have to realize that someone like myself really, really wants to believe that Razib Khan is just a stupid bigot, and Charles Murray is just a practitioner of “pseudo-science”, and that all the decades of scientific work by racialists is all hokum like astrology.

However, when all your side can come up with is sophistry and metaphysical arguments for why we can’t believe what is in front of our own eyes, it makes it hard, actually impossible, to believe anymore. I doubt, and the increasing evidence of bad behavior and sophistry on your side only makes me doubt more. At the end of the day, I want to wake up feeling like I have intellectual integrity, even if some @$$#@!& is going to call me racist or sexist on account of it.

A couple of things here:

1) “Almost as pleasurable as the revelation that Stephen Jay Gould and not Galton was the actual fraud!” This is, more or less, false: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1002444. (published in same journal as the famous/meaningless ‘refutation’).

2) “However, when all your side can come up with is sophistry and metaphysical arguments for why we can’t believe what is in front of our own eyes, it makes it hard, actually impossible, to believe anymore.”

Well… the dirty truth of human genetics is that any meaningfully strong relationship between specific gene and phenotype was discovered by the 90s, and that all of genomics is people cashing in on the boom. As someone with a PhD in genomics, I have some sympathy for this. It’s a way to get science done on the public dime. Don’t mean it’s meaningful. Associations in the literature have a nasty habit of simply disappearing in different populations, even if the same alleles are present (http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001661). This puts a bit of a crimp in the argument that the relevant alleles are meaningful…

In this day and age, if all you can come up with is 10% variance explained by genetics, that is a great argument that genetics is meaningless for the trait in question. People are trying REALLY REALLY hard to come up with better numbers and they just can’t, so they overfit the data. Whatever. They have bills to pay.

When people like Razib try to say that this is just the beginning for human genetics, it is again disingenuous. We discovered most really meaningful associations decades ago; at this point we are just scraping for funding by invoking complicated frameworks like GCTA. Which is in turn a very clever statistical trick, but it’s more than anything a way to emphasize that the associations are so hand-wavey that they might as well not exist. We exhausted the statistical power of GWAS decades ago to find common variation, e.g. the variation that you’re talking about, that was of large enough magnitude to make a real difference in light of variable penetrance.

Note that when 10% of human IQ variation is explained by allelic variation, this is negligible compared to the Flynn effect, whereby >2 SD of IQ variation can be (and has been, across cultures and decades of the 20th century) gained by education, language proficiency, nutrition, and a changing world. In short, the HBD people are at best dumbasses, and most charitably just pushing their racist shtick. Again, most of them probably have bills to pay. If you’ve stapled your meal ticket to white supremacy it’s hard to give up. The scientists can at least argue that they were just trying to finance their non-racist research.

“within 5 years we will know the answer”

You sure seem to think you know it already! I’m not saying it is unknowable. I’m saying it is unknown and difficult to know. To put it mildly, there are confounding factors. No metaphysics here.

I think it is you who can’t see what is “in front of your own eyes”–the impact of centuries of poverty, colonialism, and racial oppression; the nature of intelligence; the relationship between cultural difference and child development; etc. If you are on the autism spectrum (which I assume you are, given the style and substance of your posts), it is probably hard for you to see and understand this other stuff. When people are a mystery to you, it is comforting to think that people are all surface and no depth, just automatons acting out their genetic code. It makes the world seem simpler and more comprehensible.

One pattern I’ve observed amongnon-white-nationalist human biodiversity people (including mainstream geneticists and statisticians) is that they tend to be men on the spectrum who have lived their life in a bubble. They might understand ants or algorithms, but when it comes to humans they typically just don’t get it. Which isn’t to say they can’t–often it looks to me like willful blindness.

The division between “genetic” and “environmental” can be misleading if much of the variation is due to what might be labeled “noise”. One might argue that noise is just the label we give to environmental variation we don’t understand, but we’re not reducing everything to the lowest level of physics here. Usually by “environment” people mean something like what is often called “shared environment” in studies of heritability, which adds up to explaining much less than 100% of variation of many traits when combined with genetics.

What if statistical analysis shows that there is a statistical probability towards genetic differences between populations that cause a statistical probability of affecting certain abilities (even though I believe the variation within populations is so wide its meaningless)? What should society do? Genetic testing of all children at birth? What will you do with this information? Ban people of certain genetic combinations from acceding to certain occupations? Condemn others to specific occupations, even though, due to variation within that population there will be many people that are capable of other occupations? Sounds like Brave New world. If I remember well, in the Bell Curve the authors wanted to stop any specific educational programmes directed towards certain populations, aguing that it was a waste of money. I think they also suggested that certain populations could be directed towards specific tasks e.g.manual labour; scientists etc.

Reading many of the above comments, I get the feeling that many of the commentators “want” to find these differences. Why, what is their agenda? I don’t get the feeling that theirs is a need for pure scientific truth.

Shame on you, Michael Schulson, for writing an article littered with hint-hint, guilt by association, baseless assertions, point-and-sputter, verbal sleight of hand, moving the goalposts, selective misrepresentation, overstretched analogies, and general sophistry.

The paragraph starting “In fact, from a genes-eye point of view, racial groupings don’t make much sense at all.” is a prime example of how to mislead without downright lying. Consider by analogy: “From a pixels-eye point of view, color groupings don’t make much sense at all. Two shades of blue can be as spectroscopically distant from each other as a red is from a purple. Colors that are called green in the United States may be called lime in Europe.” But we’re not operating from a pixels-eye POV any more than we’re operating from a genes-eye POV, and so we name groups. The fact that there are ‘lumpers and splitters’ using different levels and degrees of distinction for their groupings hardly obliterates the differences, nor does it make the labels meaningless, particularly when genes cluster in groups rather than being evenly distributed across the metaphorical spectrum!

Also, please ask whatever sysadmin is in charge of tech here to add a Preview Comment button and/or a formatting hinter. Comment sections should really stop reinventing the wheel on this point.

Hilarious of Graves to suggest that ideas aren’t policed. If that were remotely true then Khan would be writing for the NY Times and more scientists would openly acknowledge that group differences can plausibly be attributed to both environmental and genetic variation. For example, it is telling that when privately polled, far more researchers consider group differences on psychometric tests are due to both environmental and genetic variation, than due to environmental factors alone (eg. Becker & Rindermann 2016, Snyderman & Rothman 1988).

Recent studies showing a genetic origin for height differences between North & South Europeans are an example of how depending on the trait in question, people can be reasonable about average differences. North Europeans, on average, have a larger number of height increasing alleles than South Europeans, due to different selection pressures that the populations experienced in the recent past (i.e., past 10k years). There’s no reason average population differences on other traits between groups, couldn’t also be due to differences in allele frequencies.

Rather than demonising someone like Khan, people should focus on the reality that statistical differences are just that. They don’t imply a lot about individuals and they don’t affect human rights.

In general, scientists are more interested in pursuing truth—as they best perceive it—than pursuing justice, social or otherwise.

As a MIT scientist, articles that tell me to subvert my work to achieve social justice goals make me want to simply withdraw from the world even further than the ivory tower requires. If raw, honestly collected data, can be racist, I give up.

@Virgil: raw, honestly collected data on humans can be racist. Sorry buddy. Most things created by humans can be racist. We only collect the data that it occurs to us to collect, under the conditions that are amenable to collection (e.g. here and now). If you aren’t able to imagine the idea that you might have unexamined assumptions that could show up in your data, well… know thyself.

The present day is saturated with racist sequelae as soon as you consider race, because race is strongly associated with a lot of other environmental factors long before considering genetics. Inability to acknowledge confounders of income, class etc. is worse than blind; it is unscientific.

I do sympathize about withdrawing from the world. Something I think about all the time. At some point, our subjective perspectives are different from other peoples’, and sometimes those people are A) more subjective, B) more influential, and C) assholes. Which makes science different from the rest of human affairs in no way.

Race is a biological reality that affects everyone everyday, to dismiss it is nonsense.

The fact that Dr Eisen is a Cultural Marxist, ought to inform you on his equalist sentiments, they certainly have nothing to do with science or genetics in particular.

Dr Khan is a first rate scientist and science popularizer, but is being unfairly criticized for not also being a Cultural Marxist.

Sad to see such drivel getting published!

Disappointing article .All anyone should care about is what the truth is. Khan leans to the right politically (as opposed to virtually every science blogger leaning to the left)? My monocle just fell out. The corny shop-worn term ‘scientific racism’ is played out. To call Takimag WN is absurd btw.

Yeah they aren’t white nationalist. Just white supremacist.

Given their political position, geneticists like Tennessen, Coop, Eisen, and Tischoff clearly must claim that all human groups, with respect to all socially important traits, exhibit the same genetical potential on average.

I’d like to see something remotely resembling a scientific argument for that extraordinary view. Races or no races, clines or no clines, the populations that came out of Africa over 50,000 years ago — or over 2,000 generations — had virtually no genetic interaction with populations within Sub Saharan Africa — and often rather little interaction between many of their own subpopulations.

And of course the environments, both physical and social, of these human groups were vastly diverse — exactly the sort of circumstances that would seem to select for different socially and cognitively relevant traits. Moreover, it’s established beyond any reasonable dispute that many of these behavioral traits are significantly heritable.

So, again, here’s the question to which I’d like to get an answer: why would one expect that all of these groups, across all of these sorts of behavioral traits, after 2,000 generations of independent selection, would exhibit the identical genetic potentials?

If scientists adopt a strong scientific position in their own domain, as have done these geneticists, is it too much to ask them to give some kind of plausible argument for their view?

“Given their political position, geneticists like Tennessen, Coop, Eisen, and Tischoff clearly must claim that all human groups, with respect to all socially important traits, exhibit the same genetical potential on average.”

Nope. Your post is one big straw man. This is not what these authors believe or argue. Is this what passes for argumentation post among you race science types?

Instead of trying to find a way to evade my question, why don’t you and the geneticists mentioned try to answer it?

To begin with, I have never seen anything like an explicit acknowledgement from any of these geneticists that it is entirely consistent with what they know that there are significant genetic differences among separated human populations with respect to socially important traits. I have never seen anything remotely like an argument from them that these differences wouldn’t be expected to arise.

I say that “[g]iven their political position” they must claim that such differences wouldn’t be expected to rise, because their vehement if not vicious moral condemnation of anyone who even speculates otherwise (such as Nicholas Wade) can be justified morally only if they strongly believe that their science contradicts any such speculation. Certainly they give no other justification for such a condemnation. They never say, for example, that, yes, it’s entirely possible that we will find such differences, but we must never speak of them, because terrible consequences will ensue — which would at least possess the virtue of being forthright. Instead, they give every possible impression that they, as scientists, can say that any such speculation is simply wrong. No person of integrity would engage in such vicious and dishonest attacks. I conclude they believe instead that their science tells them that such speculation must be false.

And beyond all this, why won’t these esteemed scientists put together an answer to my original question: why wouldn’t such genetic differences quite readily arise, given the long separation of human groups? It’s particularly ironic in the case of Tennessen, because he said he entered the political fray so that he might go after “creationists”. But if he can’t answer this question, how is he any better than any religious creationist? They believe God created humanity independently of evolution, and Tennessen clearly believes that some kind of magical force ensured that all human groups remained the same on any social trait despite evolution.

Again, evasion seems to be all they or you have.

“What does this say about the post-racial genetics that Craig Venter imagined nearly two decades ago?”

That wealthy entrepreneur Craig Venter was a gifted salesman with a knack for telling credulous non-scientists like Bill Clinton what they wanted to hear rather than what the weight of scientific evidence already showed?

Seventeen years of intensive genomic research later, only denialists continue to uphold the popular Race Does Not Exist myth.

The subtle message that article like this promote is that somehow racial minorities would benefit from a non “science-first” approach, and that it is racist to put science above other considerations.

This is a faulty assumption. It is more likely that NOT using objective standards (a “science-first” approach) will lead to bad policy and bad interventions.

The science of race differences, including the science of IQ has been taboo for three decades now, and at least in America, race relations seem to be at an all time low.

So if you have some evidence for why making science difficult to do, or putting evidence second to other considerations is BETTER for disadvantaged minorities, I would like to see it.

This is a very weak article. Though it braves to peer a little deeper into the abyss, it is much the same as these articles denouncing scientific racists have been for 20-30 years.

It gives the distinct impression that the writer is intentionally giving the wrong answer to a question he did not understand.

Mr. Schulson, you use rather a lot of words in the service of defamation here. If you’re interested by these ideas, study them properly instead of superficially. If you fear damage to your career by openly thinking about them, stay quiet. But don’t look for ways to indulge your curiosity and then run scared, wrapping your thoughts up in Brezhnevian vagueness and sophistry, especially when it means besmirching honest people. You can tell yourself whatever you like, and I know we’ve all got to make a living. But this was a dishonorable piece of work.

Where has the article defamed Razib? You can look askance at the article’s use of weasel words, but nothing in it is factually inaccurate that I can see.

I am the only one who miss James Watson’s opinion on the altered behavioural traits of different human populations/races? I think his scientific knowledge on this field is at least equal with Venter’S or Eisen’s.

“If the reader is now convinced that either the genetic or environmental explanation has won out to the exclusion of the other, we have not done a sufficiently good job of presenting one side or the other. It seems highly likely to us that both genes and the environment have something to do with racial differences. What might the mix be? We are resolutely agnostic on that issue; as far as we can determine, the evidence does not yet justify an estimate.”

Pg 311 The Bell Curve

Razib Khan’s scholarship is shallow and hollow. He hardly knows or acknowledges the implication s of evolutionary genetics in relation to human diversity. He a is conceited braggart …

Razib Khan’s scholarship is shallow and hollow. He hardly knows or acknowledges the implication sof evolutionary genetics in relation to human diversity. He is conceited braggart …

“Faced with that challenge, Khan may be a textbook example of what geneticists should not do: namely, focus on the science alone, and act as if the context doesn’t matter. “The science is always prior to everything else,” Khan told me. “Everything else is just commentary. If the commentary comes before science, that’s a problem, but that’s how a lot of discourse works. I understand. I’m not trying to be naive about it. But the reality is that’s not how I work.””

Given how much ethical/legal/societal implications research has been funded as part of NIH’s spending on genomics, this is one of the most stupid things I’ve ever seen Khan say.