In Flint, Bad Blood Tests Follow Bad Water

Hundreds of residents of the beleaguered city of Flint, Michigan, are receiving letters informing them of yet another reason to be alarmed about their ongoing water crisis: Faulty testing equipment may have resulted in “falsely low test results” for blood lead levels.

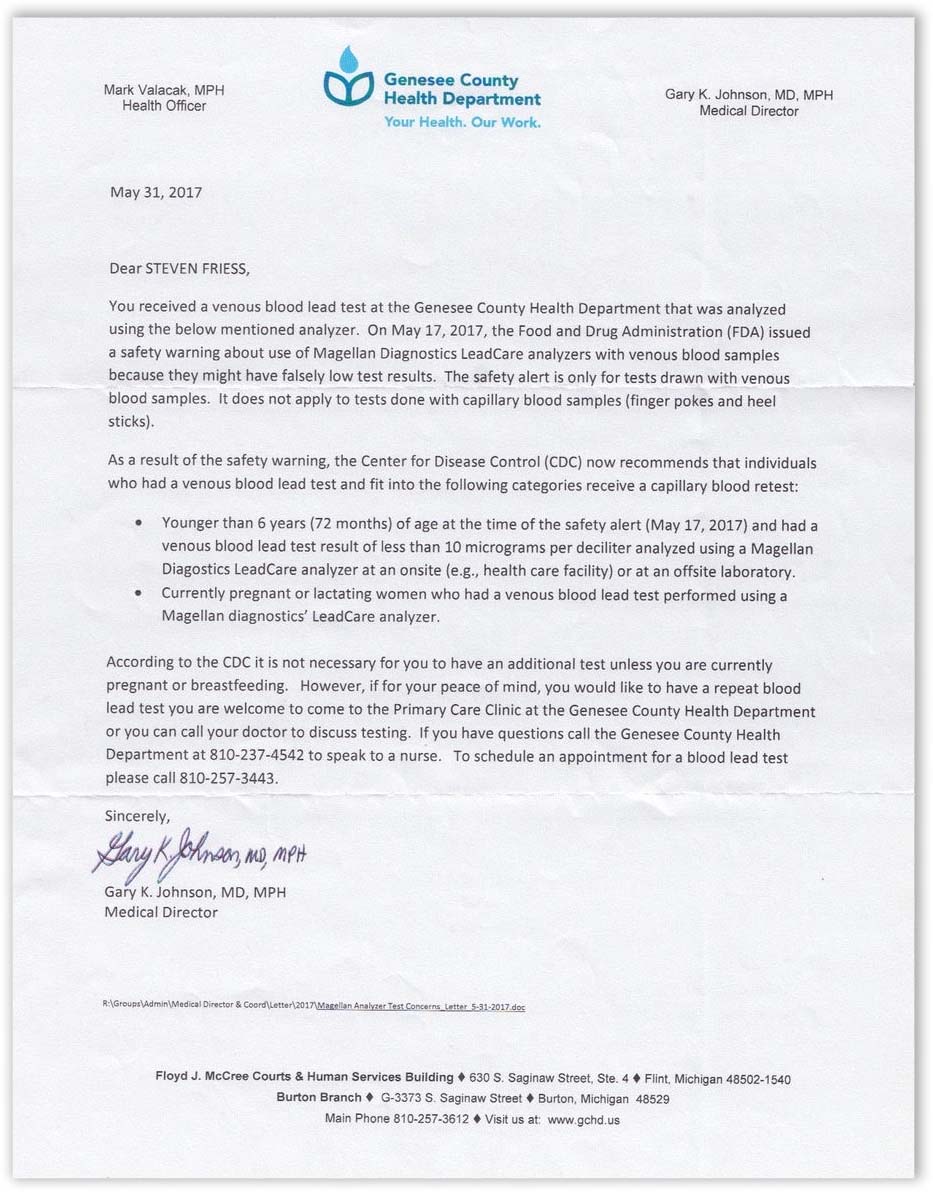

This letter, sent to the author, is one of hundreds sent to residents in and around Flint, Michigan since the beginning of the month. Click the image to view larger version.

The letter, dated May 31, cites a safety warning — issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 17 and later updated with a manufacturer’s equipment recall — regarding LeadCare-branded venous blood draw analyzers produced by Magellan Diagnostics. Flint residents who were under 6 years of age at the time of the safety warning and who received a venous lead blood test result of less than 10 micrograms per deciliter anytime from the beginning of 2014 until May of this year are being advised in the letter to be retested. Currently pregnant and lactating women who received the test — as well as anyone seeking “peace of mind” — are also encouraged to seek retesting.

Experts, however, suggest that because lead leaves the bloodstream over time and accumulates in organs, bones, and teeth, new tests will provide little insight into the severity of lead exposures that occurred during the height of the Flint water crisis — precisely when the faulty testing equipment was being used. The city infamously switched its water source to the polluted Flint River in April 2014 and failed to add the requisite corrosion controls. As a result, lead leached from water pipes and poisoned the water sent to Flint’s homes and businesses.

“There’s nothing we can really do to find out what [the exposure level] really was back then,” said Laura Sullivan, a mechanical engineering professor at Kettering University in Flint who sits on both city and state advisory boards addressing the Flint water crisis.

The problem of inaccurate testing is likely to extend well outside of Flint, given that many municipalities are struggling with aging, lead-infused infrastructure. “This problem is going to impact on East Chicago, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Baltimore — any city that has a problem with either lead in water or lead in soil or lead in paint,” said Dr. Jerome Paulson, a professor emeritus in both pediatric medicine and environmental and occupational health at George Washington University. “It’s not just Flint. It’s everywhere across the country where people thought they had a handle on what the blood lead levels were in children in the community.

“This throws a monkey wrench in the whole system,” Paulson said.

The faulty tests will also likely undermine aggregate exposure data culled from the Flint crisis and now being used by scientists to better understand the impacts of lead from intense, long-term exposures. The Magellan problem, Sullivan suggested, means that the data — much like the water itself — is now contaminated.

The health district in Genesee County, which contains Flint, issued the letters to some 600 families, although the City of Flint issued a statement saying that according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, the blood of only 128 children under 6 years old had been taken by venous draw and analyzed with Magellan equipment. The rest, they said, were taken by finger pokes or heel sticks in a method known as capillary draw.

When pressed by Undark, County Health Officer Mark Valacak said in an email message that tests for 335 adults and 225 children were analyzed with Magellan’s faulty devices. (This reporter was among the recipients of the letter, after having submitted to a lead level test in Flint last summer as part of his report on the crisis. The test results showed lead levels nearly triple the reference level set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, although to date he has exhibited no obvious symptoms of lead poisoning.)

Valacak acknowledged the limited scientific value of a retest, but said the department was attempting to be sensitive to the city’s historic lead exposure disaster. “Because of the distrust in this community, we needed to be open and transparent and let everyone know,” he said. “We’re limited on our ability to test for lead. It doesn’t necessarily mean if you got a low test you weren’t previously exposed.”

The FDA said the Magellan equipment gives accurate lead readings for blood taken via capillary draw. “As such, the FDA believes that most people will not be affected by this issue, as a majority of Magellan lead tests currently in use in the United States are conducted using blood obtained from a finger or heel stick,” FDA spokeswoman Tara Goodin said via email. Still, Goodin also noted that the Magellan devices are “the only FDA-cleared lead test systems and a primary source of blood lead testing in doctors’ offices and clinics in the United States. However, other testing methods are available, including mass spectrometer and atomic absorption testing, at larger-capacity [CDC]-approved laboratories such as reference labs.”

The CDC recommends retesting a child via venous draw if a capillary draw finds a blood lead level higher than 5 micrograms per deciliter. Some residents suspect that the 128 children may have been subjected to the venous test after an especially high capillary draw, although Valacak said he does not know the circumstances of these venous draws. In any event, if the faulty tests underestimated lead exposure levels, it also may have caused different treatment decisions than an accurately high reading, said Melissa Mays, a Flint mother whose activism forced the city and state to acknowledge that Flint’s water was contaminated after months of denials and dismissals of residents’ concerns.

“That’s absolutely terrifying,” she said Monday. “My cynical mind tells me that first they’re saying only 120 or so are too low. Then they’ll come back and say, ‘Oh, we found thousands of tests that were too high. You were never poisoned to begin with. You’re fine.’”

The news of the Magellan test problems comes at a time when state officials say the Flint water crisis is subsiding and that water quality has returned to safe levels. The crisis began when state and local officials overseeing the impoverished city of Flint, which was under the management of a state-appointed emergency manager, decided to stop taking water from a Detroit treatment system in an effort to save money. Eventually it was determined that a series of blunders at the Flint Water Plant resulted in contaminated water that was deemed responsible for abnormally high lead levels in children as well as a Legionella outbreak that killed more than a dozen people.

Lead exposure is toxic to humans and particularly so for developing children, who can see developmental delays, increased vulnerability to disease and emotional problems — although science has yet to pinpoint exactly what the impacts are and how they can be fully detected and mitigated.

After the crisis became major national news in late 2015, the water system reverted to taking Detroit’s water and added extra anti-corrosion chemicals to re-coat the interior of the city’s pipes with a biofilm that prevents lead leaching. Meanwhile, tens of millions of dollars have poured in to provide bottled water, distribute faucet water filters, and replace lead and galvanized steel service lines. To date, almost 1,500 pipes have been replaced; it is believed there may be more than 18,000 still in service.

The Magellan test revelations reignited the outrage of many who believe authorities are once again trying to downplay the state of things — as Gov. Rick Snyder admitted his administration did at the height of the crisis — in order to save money.

“Everything that’s come out has been, ‘It’s not that big a deal, you’ll be fine’ since day one,” Mays said. “It’s that same messaging. … I have no trust for them and they’ve done that to themselves. How do we know that other tests aren’t too low either from other labs or other lab equipment?”

The FDA issued no alerts regarding other lab equipment or techniques related to lead testing. On Tuesday, Catherine Lufkin, director of marketing for Magellan, said the company is “actively working with the FDA to resolve the recent action and until resolution we are unable to comment.”

“It’s all probablys and maybes and approximatelys,” Mays said, clearly exasperated. “They cannot give any solid answers. When people are thinking about their kids’ health and their own futures and everything, probablys, maybes and approximatelys are not very comforting.”

Steve Friess is a former technology and politics senior writer for Politico whose freelance work appears regularly in Time, BuzzFeed News, New York Magazine, and Al Jazeera America, among other publications. He is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan.