The Curious Case of Motherhood and Longevity

Ever feel as if motherhood literally sucked the life out of you? Well, there’s some science to back that up. A recent study in the journal PLOS One reported that the more children a woman gave birth to, the faster she aged.

The study, which looked at DNA in 100 postmenopausal women, found that those who’d experienced more pregnancies and births had increased levels of oxidative damage — an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants that is an indication of accelerated cellular aging. The authors declared their findings “the first evidence for oxidative stress as a possible cost of reproductive effort in humans.”

But wait: Maybe having children revitalizes you, keeps you young. Because the week before that study was published, another had come out — in the same journal — showing that the more children a woman gave birth to, the more slowly she aged.

That study, on 94 women with an average age of about 40, found that over the course of 13 years, those who gave birth to more children had longer telomeres, the protective casings at the end of a DNA strand. Like a candle that burns down every time you light it, telomeres get shorter each time a cell divides. The authors suggest that elevated estrogen levels in pregnancy may protect DNA from the damaging effects of oxidative stress.

Individually, such studies make for irresistible headlines, but few news stories acknowledge the persistently contradictory nature of findings in this area. We want the answer to be simple, but it just isn’t. Poke around in the literature and you will find as many articles describing the protective effects of childbearing as those that refer to it as utterly depleting.

How could having kids affect health and longevity in such disparate ways? Why can’t we definitively say how pregnancy will affect any human body?

“I don’t think there is a simple answer,” says Grazyna Jasienska, head of the Human Reproductive and Evolutionary Ecology group in Poland and a co-author of the study showing accelerated aging in mothers. “It’s interesting because it’s complicated.”

Nearly 15 years ago, Jasienska established the Mogielica Human Ecology Study Site, which collects data on the inhabitants of five villages in the mountains of southern Poland. It’s a rural population in which women still perform a lot of manual labor on small farms. She was attracted to the population’s broad fertility rate: from zero to 16 children.

“We’re comparing women with five kids with women with 12 kids. This makes it possible to really look at the costs of reproduction,” Jasienska says.

Life-history theory asserts that since the body has a finite amount of energy to work with, energy put toward reproduction is energy not spent on self-maintenance. It’s maternal martyrdom at the cellular level. In most species, increased reproduction is linked to decreased lifespan. This is the theory researchers expect to confirm when studying how childbearing affects longevity in humans, but apparently, it isn’t quite that cut and dried.

“Although the relationship between women’s fertility and their post-reproductive longevity has been extensively studied, the nature of this relationship remains unclear,” the authors of yet another PLOS One article declared in December 2015. “A meta-analysis of 31 studies on this topic did not show a consistent pattern. The relationship … can be negative, positive, or absent.”

Childbearing comes with a vast array of variables: maternal nutrition, disease risk, time between pregnancies, breastfeeding duration, number of pregnancies, even the baby’s gender. Boys tend to grow faster in utero, to weigh more at birth, and to make higher lactational demands, so “having sons may be more energetically expensive for mothers than having daughters,” Jasienska explains in “The Arc of Life.”

And breastfeeding is even more “energetically expensive” than pregnancy. Women who exclusively breastfeed their babies need to eat an extra 640 calories a day; only 300 additional calories per day are needed during the last two trimesters of pregnancy. It’s a factor that tends to be neglected by research into the relationship between fertility and longevity.

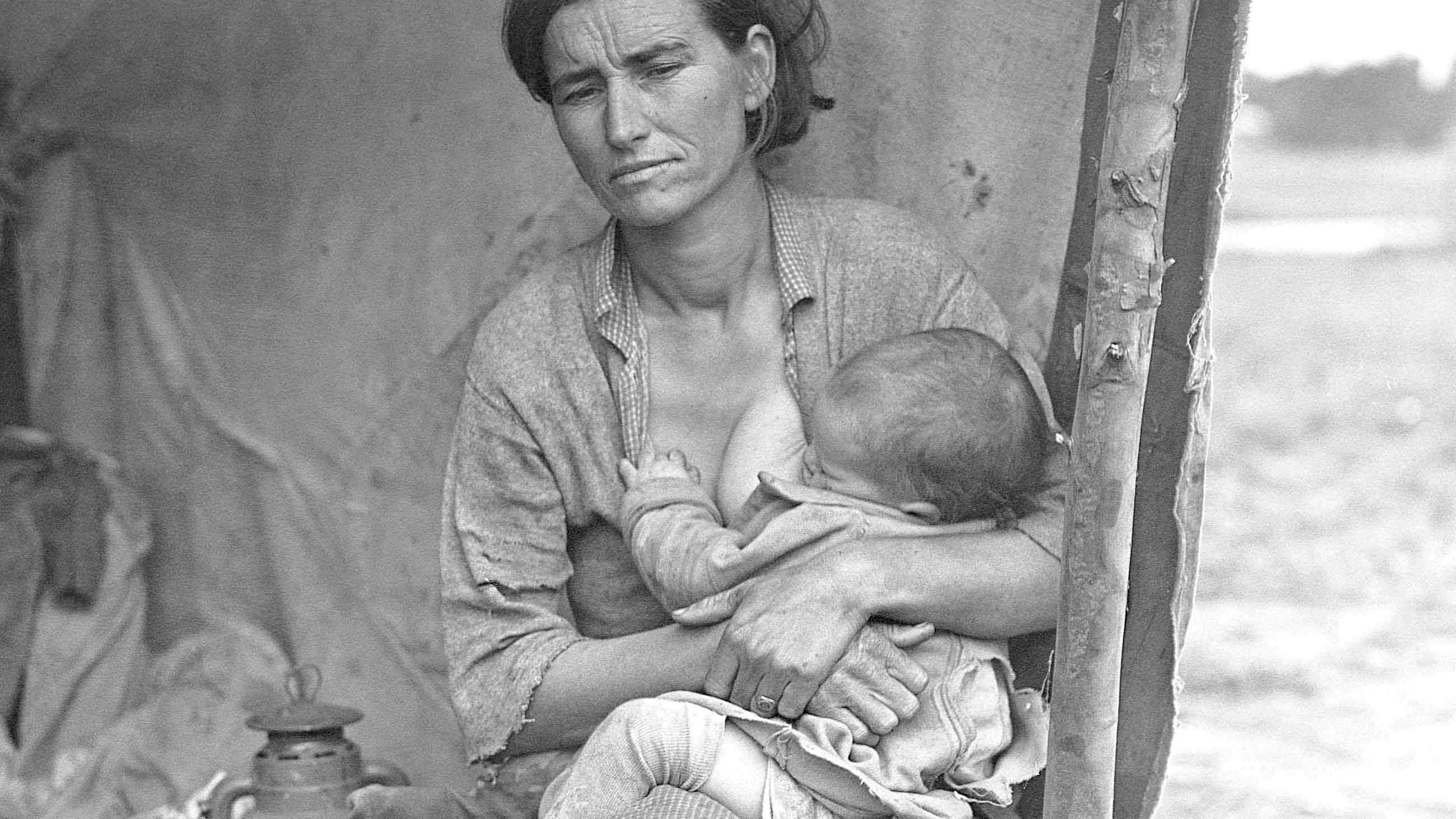

“The [overall] costs are not the same for someone who eats well compared to someone whose food intake can’t cover the excess energy needs of pregnancy and lactation,” Jasienska says. “[In] well-off women who have many children, we see increases in longevity. For someone in an economically developing country, for example, the costs of reproduction are much more intensely received by the organism.”

Childbearing has been shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis, Jasienska noted. Conversely, the hormones involved in pregnancy and lactation can reduce the risk of pancreatic and reproductive cancers. So a woman’s lifestyle habits and baseline risks for these diseases will all play a part in the ultimate effects of childbearing. Did having kids end your drinking and smoking days, or do your children drive you to drink? According to Jasienska, this is why some studies see no effect: “because everything evens out.”

Moreover, she says, having a child every year is much different from having, say, one child every four years. “The question is: is the damage reversible? For women who have children close together, is [the body] only repairing itself a little, but accumulating damage that leads to problems at an older age?”

Not all studies account for all of these variables, but that doesn’t mean their findings aren’t valid, just that we should understand the limits of their broader applicability. “To study all of what reproduction does and how — I’m not sure if a perfect study is possible at all,” Jasienska says.

Half a world away, in the highlands of Guatemala, Pablo Nepomnaschy found a population to study with similarly wide-ranging fertility rate: between one and 10 children. Nepomnaschy is the director of the Maternal and Child Health Lab at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, and co-author of the study that linked childbearing with longer telomeres. He began collecting data on a group of indigenous Kaqchikel Mayan women in 2000, expecting his findings to support life-history theory. Instead, he found the opposite.

“I was very puzzled,” says Nepomnaschy, speaking from the field in Guatemala. “So I had my team redo the results, but they kept coming out the same way… I soon discovered we were not the only ones to find these results, but nobody had a good explanation of why.”

He says he then happened upon a study in which researchers in Israel found that both mice and humans exhibited faster tissue rejuvenation after pregnancy. The fetal cells that mingle in the mother’s organs and bloodstream, the authors suggested, may act like an injection of youth.

“I was blown away by [these results] … reproduction is costly, but maybe it’s associated with biological mechanisms that slow down aging,” Nepomnaschy said. On average, women live longer than men. So there may be something built into female DNA, or into the process of reproduction, that helps maternal cells recover from being temporarily neglected.

Perhaps it’s that there’s an optimum number of human offspring. A recent analysis of 18 cohort studies, seven of which included men, uncovered a J-shaped association between number of children and risk of mortality from all causes: Parents of one to five children had a reduced risk of death compared with those who had either no children or at least six. For both men and women, the greatest reduction was for parents of three to four children. Other large studies cite the magic number as two.

Since you’d have to start young and have relatively short periods between pregnancies to give birth to six kids, this assessment is in line with Jasienska’s concern about the body’s ability to withstand such demands. Another possibility is that the genes linked to increased fertility are also associated with increased levels of oxidative stress, as well as increased susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Pregnancy is one thing: parenting is another. Do social support systems after birth — or lack thereof — affect a mother’s recuperation? Surely decreased sleep and increased stress play roles here, too.

Nepomnaschy says that as with childbearing, the biological costs and benefits of childrearing may vary by population and counteract each other. Jasienska explains that on one hand, “if parents have limited resources and must share them with many kids, this is not going to be good for their health. On the other hand, children help their parents and also take care of aging parents. Our study showed that women with high fertility have shorter life span, but in men, number of daughters is related to longer life span.”

It’s likely that no study will ever separate out all of the factors to definitively say how pregnancy and parenting affect the body. Especially not if what we’re looking for is a simple answer — an irresistible headline that purports to be applicable to anyone.

Olivia Campbell, a science journalist and essayist, is a regular contributor at New York Magazine. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, Scientific American, Quartz, VICE, Pacific Standard, and STAT News.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I appreciate that the author acknowledged the one simple fact that the media, government and medical community, particularly the public medicine sector, never seem willing to admit as regards human beings and health: Simple answers are almost always, ultimately, wrong answers. The evolution of human beings has been incredibly complex, and it’s rare to find a single animal species that has managed to occupy and function in as many habitats as human beings. As such, human physiology rarely admits to singular operation. When it comes to pregnancy, we know that that the bodies of a mother and the fetus behave both cooperatively and antagomistically, making matters even complicated. Layer in the social factors that directly and indirectly affect human health and reproduction, and you have fewer and fewer generalities that apply to individual cases. As such, it may be at least or even more productive to look at the individual to consider what is and is not applicable to groups, and at what degree of association, than it is to generalize and then make endless exceptions.

from the fact that hunter-gatherers tend to have no more than one child every four years, the same as our chimpanzee and gorilla relatives, I have drawn the conclusion that the high birthrate of settled peoples is another negative side-effect of our invention of agriculture (which I call the Original Sin). Closely-spaced pregnancies wear women out, particularly if they get inadequate food and rest. Often, women become anemic, which leads to excessive bleeding at childbirth–frequently resulting in maternal death, if adequate medical care isn’t available. (also: closely-spaced siblings aren’t often pleased–the older child is jealous, the younger sometimes underfed, if the mom keeps nursing the older sibling. Children who are at least four when a new child arrives are weaned, house-broken, verbal, tend to have friends, and can actually be helpful)

In my personal family history, my mom had her first child at 38, and reached menopause at 40; I got pregnant first at 17, had my last child at 33, and was still menstruating a few years ago (I am 62). I had 3 abortions, 3 live births, and one 5-month-along miscarriage, which could have cost me my life. I nursed my daughters until they each were 3–my poor son got deprived of my milk when I got pregnant when he was 5 months old, got some more ages 10-19 months, when I got pregnant with his younger sister–he is still, at age 31, susceptible to the ear infections that plagued his formula-fed childhood–his sisters might have gotten one ear-infection apiece as children. If I was an illiterate peasant whose last child was born in 1916, like my Cossack grandma, I would also have had 9 children or more. Instead, I was an educated American middle-class kid who graduated high school in 1972. Roe v Wade was passed right before I had my first abortion. One way or the other, the state paid for my OB-GYN care all my reproductive life, birth control, abortions and a hospital birth (we paid cash to the lay midwives present at my oldest child’s birth at home; my son’s dad was the midwife at his birth at home)

I am in pretty good health at 62; my step=children’s mother is in exemplary health at 80–she bore her first child at 25 and her sixth at 43. (she also doesn’t smoke, use other drugs except maybe pot, and drinks only occasionally)

I have also born 8 children (1999-2013) with 2 miscarriages in between and just turned 40. My body is tired, but I think that is related to back -to-back pregnancies with minimal recuperation as well as the fact I live where it rains a LOT and I dont feel like I can get out and exercise as much.

But overall- I have wonderful pregnancies and I haven’t aged. I look like I did when I was 22 and people constantly comment on how I look like an older sister to my 18 yr old.

Everyone out there, this duplicitous Senator

Changed her mind today and cast a vote that will lead the way for the collapse of Medicaid and jeopardize the lives of children and elderly who need medical attention.

Yell, “Shame” over and over! She deserves

ridicule and foulness because of her horrible action.

West Virginia

Senator Shelley Capito

Call 202-224-3121

https://www.capito.senate.gov/contact/contact-shelley

https://m.facebook.com/senshelley

https://mobile.twitter.com/sencapito

https://www.instagram.com/sencapito/

304-347-5372

304-262-9285

304-292-2310

202-224-6472

Retweet

i have eight children 1992-2016 i never go to the doctor dont need to im fighting fit feel same now with my six month old as i did 24 years ago.i smoke drink and laugh all the time something like the happiness factor surely should play a part in all theese calcululations!

Thank you for this fascinating article. In my experience of bearing nine children (1996-2014), I have felt physically depleted; truly, in college I was an inch taller and ten pounds heavier. However, this challenge to my physical health, along with the incredible sense responsibility to remain vital into my golden years, has motivated me to seek the healthiest lifestyle possible. I cannot kid myself about aging like many of my friends and family, thus I’ve adopted a centenarian lifestyle early and am reaping the benefits!

how old are you sarah?