Last September, Eliezer Masliah, a prominent Alzheimer’s disease researcher, stepped away from his influential position at the National Institutes of Health after the organization, where he oversaw a $2.6 billion budget for neuroscience research, found falsified or fabricated images in his scientific articles.

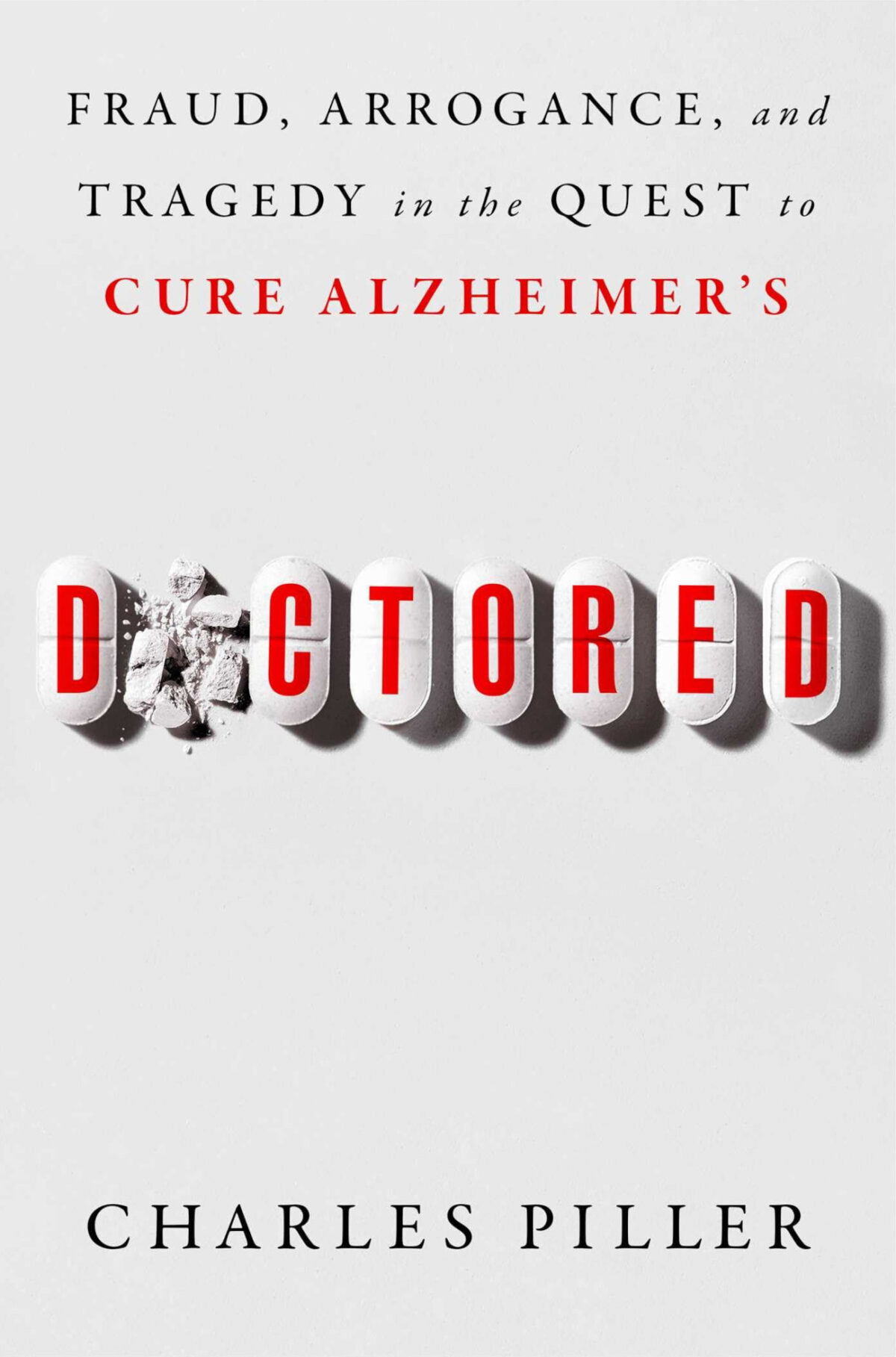

BOOK REVIEW — “Doctored: Fraud, Arrogance, and Tragedy in the Quest to Cure Alzheimer’s,” by Charles Piller (Atria/One Signal Publishers, 352 pages).

That same month, the Securities and Exchange Commission announced neuroscientist Lindsay Burns, her boss, and their company would pay more than $40 million to settle charges they had made misleading statements about research results from their clinical trial of a possible treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

Also in September: A $30 million clinical trial to study a stroke treatment developed by Berislav Zlokovic, a well-known Alzheimer’s expert, and his colleagues was canceled amid an investigation into whether he had manipulated images and data in research publications. Shortly thereafter, Zlokovic, director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the University of Southern California medical school, was placed on indefinite administrative leave.

Is there a pattern here? And, if there is, can neurology patients trust treatments that are based on published scientific research? That is what Charles Piller, an investigative reporter for Science magazine, examines in “Doctored: Fraud, Arrogance, and Tragedy in the Quest to Cure Alzheimer’s,” and his analysis is not comforting.

As for the first question — is there a pattern? — Piller’s relentless reporting reveals that dozens of neuroscientists, including some of the most prominent in the world, appear to be responsible for inaccurate images in their published research. Those problematic images have prompted many of their articles to be retracted, corrected, or flagged as being “of concern” by the journals in which they were published.

The other question — can neurology patients trust the treatments they are being offered? — remains unanswered despite Piller’s excellent effort.

His focus is on Alzheimer’s disease, a devastating condition that steals patients’ memory and their ability to take care of themselves, and his investigation is timely. Nearly 7 million Americans over age 65 have Alzheimer’s, along with an estimated 200,000 younger adults.

Dozens of neuroscientists, including some of the most prominent in the world, appear to be responsible for inaccurate images in their published research.

Piller’s attention was pulled to the disease in December 2021 when he got an intriguing tip from a dementia researcher. “He produced convincing evidence that lab studies at the heart of the dominant hypothesis for the cause of Alzheimer’s disease might have been based on bogus data,” Piller writes.

The hypothesis in question surmises that Alzheimer’s is caused by a build up of a protein called amyloid in the brain; removing that protein would point to a cure.

Since 2021, the Food and Drug Administration has saluted that idea by approving three drugs that have been proven to reduce amyloid in the brain; the first one has been discontinued, but the other two are being offered to patients with early Alzheimer’s.

Piller — and many neurologists — are skeptical of the hypothesis because, at least so far, removing amyloid plaque is nothing close to a cure. He describes Leqembi, one of the two drugs currently available, this way: “Alzheimer’s patients lost their ability to remember, think clearly, and live normal lives only slightly less rapidly than others taking a bogus treatment. The drug offers so modest a benefit that doctors and patients might not perceive any effect whatsoever.”

He set out to learn whether the so-called “amyloid mafia” — influential neuroscientists who promote the hypothesis — have generated or relied on bad science that bolstered the amyloid argument and, in so doing, stymied other avenues of research. “For decades, proponents of the dominant amyloid hypothesis have sidelined, starved for resources, and even bullied rebels behind other promising notions of how to treat Alzheimer’s,” Piller writes.

His specific focus is on images — particularly Western blot images and micrographs — that bolster research findings. In “Doctored,” he takes a deep dive into two cases. The first is the story of Cassava Sciences, a Texas company that developed a potential Alzheimer’s treatment based in part on the amyloid hypothesis. In June 2024, a federal grand jury indicted Hoau-Yan Wang, a professor at the City University of New York (CUNY) School of Medicine, for allegedly defrauding the NIH of about $16 million in federal grant funds by fabricating and falsifying scientific data in grant applications on behalf of Cassava Sciences and himself.

The indictment followed a CUNY investigation that found many of Wang’s scientific publications included inappropriately altered images and showed “evidence highly suggestive of deliberate scientific misconduct.”

Lindsay Burns, Cassava’s senior vice president of neuroscience until the scandal broke, co-authored many of Wang’s scientific papers. She and Cassava’s chief executive officer consented to the government’s $40 million-plus penalty without admitting or denying the allegations against them.

The book also zeroes in on Alzheimer’s researcher Karen Ashe, a University of Minnesota professor, and her colleague, neuroscientist Sylvain Lesné, who claimed to have found a protein — amyloid-beta star 56, or Aβ*56 — that Ashe touted as “the first substance ever identified in brain tissue in Alzheimer’s research that has been shown to cause memory impairment.” (Lesné has resigned from University of Minnesota effective Mar. 1, 2025.)

After their finding was published in 2006, the study was cited thousands of times by other researchers, Piller writes. But in 2022, another scientist reported to the NIH and several journals that Lesné, sometimes with Ashe as a co-author, had published at least 13 papers pertaining to Aβ*56 that appeared to have doctored images. Last year, the journal Nature retracted the original 2006 article, at Ashe’s request, saying figures “showed signs of excessive manipulation” and the data cannot be verified.

Piller — and many neurologists — are skeptical of the amyloid hypothesis because, at least so far, removing amyloid plaque is nothing close to a cure.

While reporting those stories for Science, Piller learned of other examples of apparently manipulated images, prompting him to dig into the situation in a novel way. He organized a group of image-analyzing experts to examine a sample of the published papers from dozens of Alzheimer’s researchers whose work had been called into question on PubPeer, a website where individuals can post concerns about the integrity of published papers. Their analyses uncovered 571 papers with problematic images that call into question the integrity of the authors and the validity of their work.

“It was the first major attempt to systematically assess the extent of image and data doctoring across a broad range of key scientists addressing any disease,” Piller writes. “By 2024, it had sparked numerous corrections, retractions, institutional reviews, government investigations, and lawsuits.”

Meanwhile, many Alzheimer’s researchers have relied on those now-questionable papers to inform their own research. Those articles have been cited 77,655 times and cited by active patents 478 times, according to Piller.

Despite the worrisome picture they paint, the people who identified the problem images — and other experts Piller recruited to review their work — do not accuse their fellow scientists of fraud. Image-doctoring does suggest probable or apparent misconduct, Piller writes, but a definitive conclusion requires comparing the images with lab notebooks and other sources of data that were not available to the reviewers.

Unfortunately, Piller’s many tangents and the confusing organization of his material make for rough reading. For example, the first five chapters are devoted to detailed biographies of individuals who might be considered main characters of the book. As the narrative unfolds, though, the hundreds of minute details in those 50 pages are never shown to be particularly relevant. Piller’s exhaustive reporting reveals why Lindsay Burns’ grandfather was monitored by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, for instance, and that D-Day tourism drives the economy in the small French town where Sylvain Lesné was born.

But by the end, many readers may find that the main character of Piller’s story is the state of neuroscience research, rather than any individual scientist. By then, the reader is drawn into Piller’s assemblage of experts — from armchair science sleuths to important neuroscientists — and their painstaking efforts to uncover bad science in Alzheimer’s research.

Piller’s book brings to mind “Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health,” a 2024 book by Marty Makary, the surgeon nominated by President Donald Trump to become the next FDA commissioner. In that book, Makary laments that the institutions and publications that fund and report scientific findings perpetuate a kind of groupthink in which some ideas are heavily promoted to the detriment of others.

Many readers may find that the main character of Piller’s story is the state of neuroscience research, rather than any individual scientist.

“Doctored” bolsters that argument, reporting that nearly half of the NIH’s Alzheimer’s budget in 2021 went to projects that mentioned amyloid proteins and the majority of later-phase clinical trials that focused on the proteins. Piller quotes neuroscientist Zaven Khachaturian, who directed Alzheimer’s research at the NIH between 1977 and 1995, and said science suffers when scientists accept an idea as infallible: “Everybody felt obligated to pay homage to the idea without questioning.”

Ultimately, “Doctored” does not prove the amyloid hypothesis is wrong — the idea is still up for debate. But it does make clear that there is something wrong in the world of neuroscience research.

Matthew Schrag, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University and the top image-sleuth guiding Piller’s reporting, sums it up this way: “Patients ask me why we’re not making more progress. I keep telling them that it’s a complicated disease. But misconduct is also part of the problem.”