In Uganda, Threatened Chimps Find Protection in Former Poachers

It is little secret that African wildlife is threatened. Human development, after all, is shrinking the native habitat of countless African species. Meanwhile, elephants are routinely and illegally slaughtered to feed the black-market trade in ivory, while rhinos are slaughtered for their horns, which are used in dubious Chinese medicines. Other animals — from birds, snakes, lizards, and other creatures — are often trapped for sale into the exotic pet trade, while still others, including monkeys, crocodiles, and tortoises, are hunted as bushmeat.

The chimpanzee, however, suffers from all these stressors. Shrinking habitat, the illegal pet trade, and the spears and traps of hunters — sometimes targeted, sometimes not — have reduced the African chimp population from approximately one million at the turn of the 20th century, to an estimated 172,000 to 300,000 today. The Jane Goodall Institute U.K. estimates that African ape populations overall “will decline by an additional 80 percent in the next 30 to 40 years.”

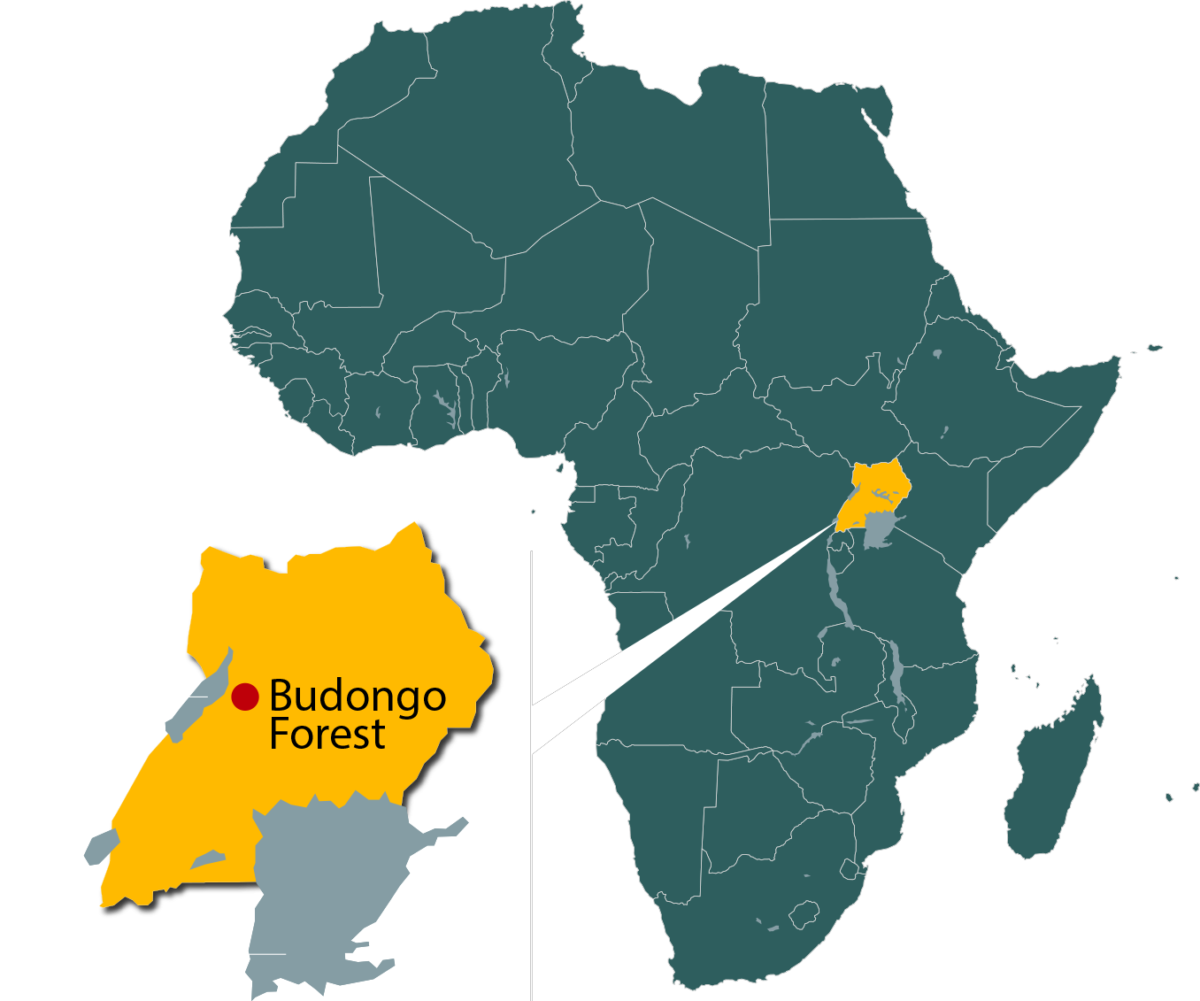

In the Budongo forest of western Uganda, veterinarian Caroline Asiimwe and her colleagues — some of them former poachers themselves — are trying to save chimpanzees, though the work isn’t easy. A war has broken out in and around this 168-square mile reserve between the estimated 800 chimps and the human populations that surround them. With their native resources shrinking, Asiimwe says, the chimps have begun scavenging for food in the cultivated fields surrounding Budongo, where human-animal conflict is inevitable. She notes that on the outskirts of another Ugandan forest, in the Muhorro-Kagadi district, chimps have killed eight children in the last five years.

Attacks go the other way too: Near Budongo, some residents have stoned chimps, attacked them with spears, and even put nails in their heads, Asiimwe says. Others have been killed for use in traditional medicine, while others are dying from illnesses — especially respiratory diseases — transmitted by humans. In other areas, chimps are hunted illegally for food, while many continue to be targeted for capture as exotic pets or for shipment to unregulated zoos around the world. But in Budongo, chimpanzees are typically collateral damage — wounded or killed in the many wire or jaw-like traps set for other animals.

These pressures are difficult to combat. Like everywhere else in Uganda, the population around Budongo is booming, with many people attracted by the discovery of oil and gas in the neighboring Murchison Falls National Park. Refugees from conflicts in northern Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo are also adding to the growth.

But Asiimwe says she is optimistic, and she is trying to save chimpanzees and other wildlife in novel ways — including drafting former wildlife poachers into the effort. The Budongo Conservation Field Station, where Asiimwe works as a conservation coordinator, is providing poachers with alternative livelihoods, and in some cases, they have been hired as “eco-guards.” Their mission: policing the forest and removing the very sort of deadly traps that they themselves once put in place.

Hear more about the Budongo field station in this month’s Undark podcast.

THE HUNT FOR TRAPS

Asiimwe and her team of eco-guards cross the Budongo Forest by car. Aggressive patrols, which can require the group to spend nights in the deep forest, can uncover as many as 400 traps in a single week.

INCENTIVIZING CHANGE

“When I save an animal that is caught in a trap, I feel so happy and relieved to see that I am able to give this life another chance,” says Asiimwe. She was awarded a prize from the World Academy of Sciences in 2017 for her work.

A LONG WAY TO GO

Although the number of illegal traps and of injured chimps had been declining, incidents have begun to rebound in the last few years, suggesting that Asiimwe’s work — and that of her colleagues — is far from over. “This is our closest cousin,” Asiimwe said. “We need to protect it.”This project was supported in part by a grant from The European Journalism Center, and is part of the series “African Women Scientists on the Move.” Marco Boscolo contributed reporting for this story.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

The traps look like an opportunity for IOT technology. Putting a GPS chip in the traps so they can be tracked from purchase through use would help identify the poachers and their activities. It might be fun to try at least. I am sure the poachers would figure it out eventually though.

So glad to hear of success stories. We need more people and initiatives like this one. The goat solution is wonderful as it addresses the needs of the people in a way that helps the chimps as well. Thank you for this article and kudos to Carolina Asiimwe.

The challenges the people of these areas and surrounding areas face are widely varied. What doesn’t change is the critical need for funding. While the following might be hard to swallow, especially for those countries that paved the way for their future based on profit derived from these exports, we need to restore the rights of the African people. Specifically oil, gas and mineral rights. These mineral rights “stolen or leased” from the inhabitants of this land Many countries have enjoyed rapid advancement and a better way of life but it was made much much easier for those individual countries with the riches looted from the African continent. It seems we are very capable of overlooking our own inhumanity as we better ourselves. Almost as if we wore blinders, but we haven’t that excuse. Many of us are so wrapped up in ourselves or other events that we fail to recognize our own xenophobic history, actions and reactions. We do little to demonstrate those traits we like to claim define us as “human”. So what might we do to change this? What might we do to precipitate change? We might start by giving these indigenous peoples or the peoples who have claim to this land through ancestry their mineral rights that were stolen long ago. Give the African continent and it’s rightful inhabitants control of the proceeds of their GDP. Put an end to leaching it through outdated European Oil & Gas Leases forced upon people without the means to refuse. Leases signed without proper council or representation in a time when people likely were incapable of understanding the gravity of their decisions. Not all of Africa has vast mineral deposits and things that may support them but the places that do should have what was and should rightfully be theirs.

Democratic Republic of Congo

Mining is the primary industry of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) also. In 2009, the DRC had over $24 million in mineral deposits including the largest coltan reserve and huge amounts of cobalt. The DRC also has large copper, diamond, gold, tantalum and tin reserves, and over a million tons of lithium as estimated by the American geological survey. In 2011, according to the latest data, there were over 25 international mining firms in the DRC.

We cannot solve all of the worlds problems but we can undo injustice. Stealing the natural resources of another country is wrong. The only real hope for these regions is in self-rule while exercising self control. They must be responsible for their future by their own actions. We are not better. Maybe wiser in certain respects but that is the road we’ve chosen. Give them choices, let them bare those responsibilities for these decisions. Sometimes all a person needs is a bit of responsibility to see the path to a brighter future. Many wrongs might be made better by simply restoring the ability of the African peoples to support themselves and some of their reconstruction ideas.

We applaud the work of fellow female veterinarian Caroline Asiimwe’s work and wish her and her team all the best luck and good fortune. She makes a true difference in our world!