‘Atomic Bill’ and the Birth of the Bomb

At 5:51 a.m. on Monday, May 21, 1956, the famed New York Times science correspondent William Leonard “Atomic Bill” Laurence watched a new universe burst into existence.

As with most profound revelations, this one took a few minutes to sink in, even as Laurence watched it unfold about 40 miles away through a set of heavy goggles. Reliable eye protection was necessary when watching the birth of a new universe, as Laurence well knew, having already done so several times in his long career. No one else among the 14 other reporters who stood around him on that 1956 morning, clustered on the flag bridge of the Amphibious Force Command Ship U.S.S. Mount McKinley (AGC-7), could boast of such exclusives.

But even Laurence had never seen anything like what he was now contemplating. Called Cherokee, it was a hydrogen bomb that moments before had been dropped about four miles off target from a B-52 bomber flying 10 miles over the northern Pacific, near the island of Namu in the Bikini Atoll. Cherokee detonated at an altitude of about 5,000 feet with an explosive force of 3.8 megatons, hundreds of times as powerful as the Trinity test that had once so awed him.

All of America’s previous H-bombs had been huge, heavy, cumbersome things. And though America had been first to build the H-bomb, the Soviet Union hadn’t been far behind, and was even ahead of the United States in coming up with an H-bomb small and light enough to be carried by airplane. Cherokee was America’s first air-launched hydrogen weapon, its first truly practical thermonuclear bomb. With its successful test, the United States had proclaimed to the world – particularly the Communist parts of it — that it now had a handy, portable H-bomb that it could easily deliver (in the Air Force’s charmingly innocuous term) anywhere on the planet.

Laurence had written articles and even a book about the hydrogen bomb, had interviewed its creators, and had contemplated its effects and explained them to his readers. But he had never seen one for himself. Now, at last, he could add the H-bomb to his credentials as America’s premier atomic oracle.

“I saw a supersun rise over the vastness of the blue-black Pacific, with a dazzling burst of green-white light estimated to equal, for a brief instant, the light of five hundred suns at high noon,” he later wrote in his book “Men and Atoms.” “Awestruck, I watched the enormous fireball expand in a matter of seconds to a diameter of about four miles, more than twenty times the diameter of the fireball of the now antiquated atomic-fission bombs that had devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For nearly an hour after the fireball had faded I watched incredulously the great many-colored cloud that had been born in a gigantic pillar of fire.”

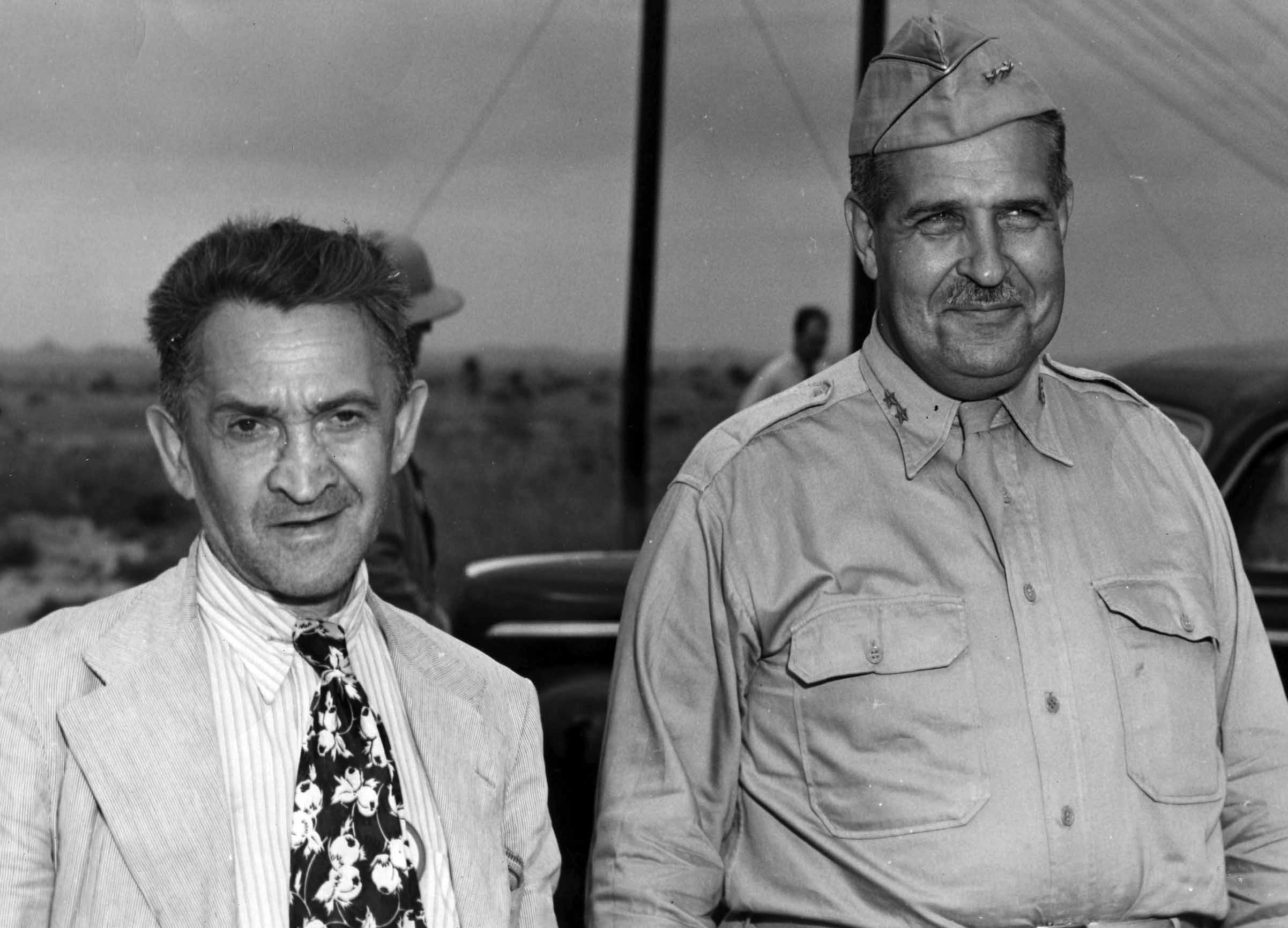

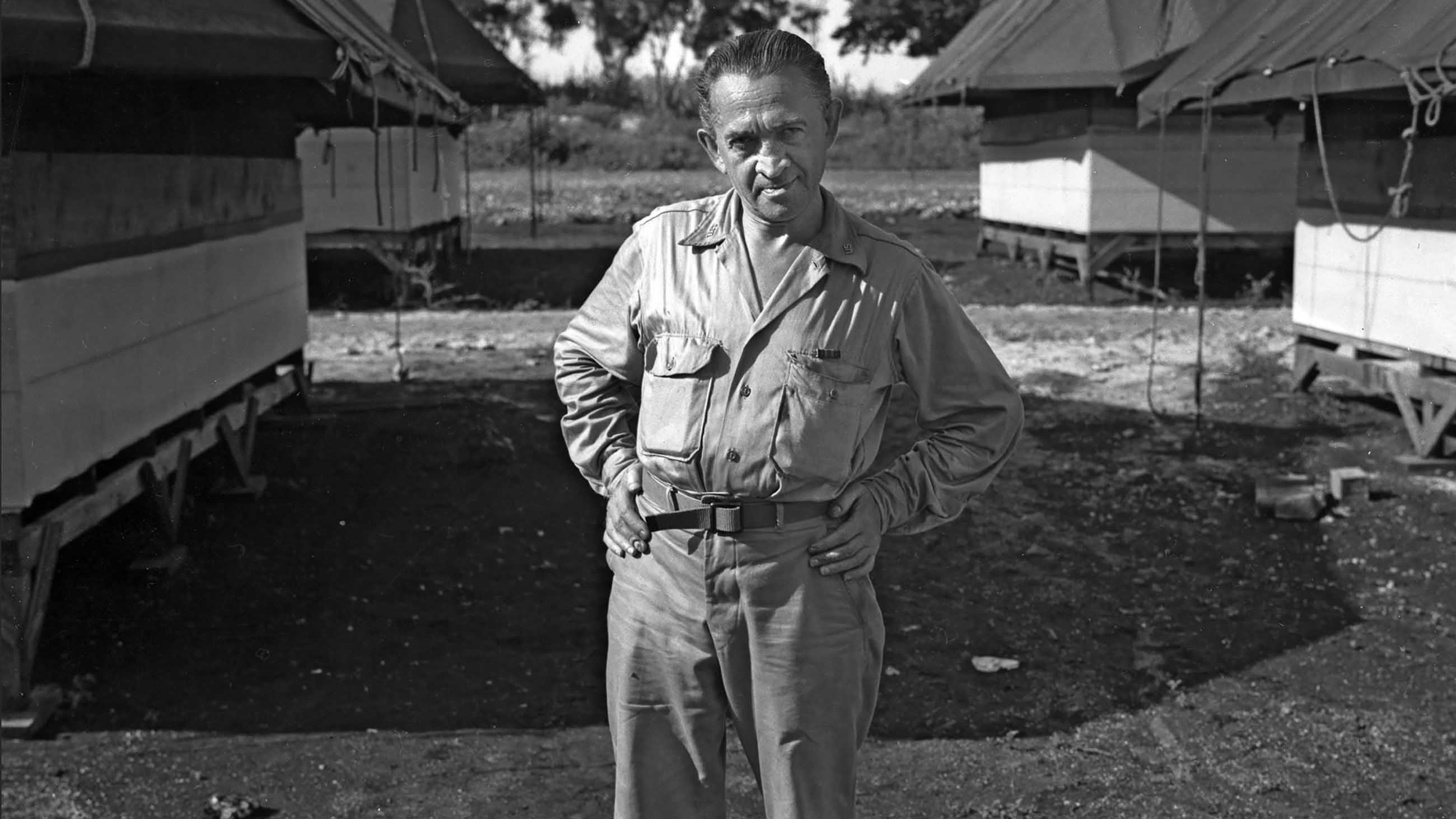

William Laurence is the great neglected celebrity of the Manhattan Project. Mentioned in nearly every account of the atomic bomb saga, from Lansing Lamont’s 1965 “Day of Trinity” to Richard Rhodes’s seminal Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Making of the Atomic Bomb,” he’s the enigmatic reporter standing on the sidelines scribbling notes while Oppenheimer, Fermi, Teller, and the other Los Alamos geniuses stand in the cold New Mexico desert one July morning to watch the birth of their creation.

Yet none of these books, the films and TV movies such as “Fat Man and Little Boy” and “Day One,” or any of the other sundry retellings of the Manhattan Project story gives Laurence more than a passing reference. After encountering this mysterious figure so many times in so many different venues, I began to wonder: Who the hell was this guy, and how did he ever get to be the only reporter allowed to cover one of the biggest stories of the 20th century?

To the nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein, Laurence was “part huckster, part journalist, all wild card … he’s improbable in every way, a real-life character with more strangeness than would seem tolerable in pure fiction.” He has also become something of a moral bête noire for some who have questioned his motivations, ethics, and Manhattan Project reporting, seeing him either as an opportunist who parlayed a lucky break into a historical exclusive or a nefarious propagandist for the military establishment.

Visual courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration, Nevada Field Office.

Yet Laurence was also, at least in his own era, one of the most important science writers in America, one whose influence, if not his lyrical and vivid prose style, persists to this day. The Princeton historian Michael D. Gordin, author of “Five Days in August” and “Red Cloud at Dawn,” notes Laurence’s seminal impact on popular perceptions of the Bomb: “[His] science-driven utopianism, stressing some of the potential positive outcomes of nuclear power and minimizing the threat to Americans … [was] strongly influential in those early years, and shaped some of the discourse even of those opposed to the positions he articulated.” Much of Laurence’s writing, Gordin goes on, “became just part of the way people talked about nuclear weapons for decades.”

For Laurence, science represented humanity’s salvation, whether through medical advances or the power of the atom. If he believed that science was “the religion of the future,” as Spencer Weart wrote in his book “Nuclear Fear,” then Laurence definitely saw himself as an evangelist. As he once proclaimed, “True descendants of Prometheus, science writers take the fire from the scientific Olympus, the laboratories and the universities, and bring it down to the people.”

Watching the Promethean fires of Cherokee “climbing and spreading outward and outward until it appeared as it would envelop the entire earth,” Laurence felt “as if one were experiencing a nightmare with wide-open eyes in broad daylight,” staggered by the realization of what such a weapon would do to New York or Chicago, Moscow or Leningrad. And then, unexpectedly and almost against his will, he found his primal terror giving way to something else.

“As I kept on watching, a second, more reassuring thought became uppermost in my mind, a thought that has kept growing ever more reassuring in the years that have followed that historic morning.

“This great iridescent cloud and its mushroom top, I found myself thinking as I watched, is actually a protective umbrella that will forever shield mankind everywhere against the threat of annihilation in any atomic war. … For no aggressor could now start a war without the certainty of absolute and swift annihilation.”

For years, Laurence had wavered, torn between his firsthand knowledge of the annihilating power of nuclear weapons and his hope that the civilian and military atom would bring about a fabled new age of wonder for humankind. The great dangers and the great promise were two separate paths, and it was up to us to choose the right one.

But now those two sides of the atom, the dark and the light, nuclear oblivion and nuclear plenty, finally reconciled themselves in Laurence’s mind. He knew he had been wrong. They weren’t separate. They were one and the same. In the face of the awesome power of hydrogen fusion, no distinctions were necessary, or even possible. Beyond the dark cloud of nuclear destruction lay the super-bright sun of nuclear promise. And he would be the one who, through his words, would help the world see that light.

For someone who spent almost 40 years as one of America’s most prominent journalists, most of them working for The New York Times, Laurence remains remarkably elusive. Even though he wrote four books and hundreds of articles in the world’s best-known newspaper, upon his death in 1977, he apparently left behind no papers, diaries, journals, notebooks, or any of the other records that would be expected of a professional writer. He and his wife, Florence, had no children, and in years of researching his life, I’ve located only one surviving person who actually knew him, the former Times managing editor Arthur Gelb, who died in 2014. Apart from his voluminous writings, the most detailed source of information on Laurence is a lengthy oral-history interview he did for Columbia University in 1964. The transcript’s more than 500 pages are fascinating, detailed, and colorful, but — given Laurence’s predilection for self-aggrandizement and factual exaggeration (qualities that also crept into the sometimes purplish prose of his professional work) — less than fully reliable.

All of which makes Laurence something of a tabula rasa upon which historians and other observers can impose a wide variety of motivations, whether neutral, benign, or sinister. In recent years, rising concerns over journalistic ethics, embedded reporters, and conflicts of interest have led critics to view Laurence’s role in the Manhattan Project as a classic example of the latter. Here was a reporter for America’s newspaper of record, tapped to serve not the interests of objective journalism but those of the military. How could such an arrangement be seen as anything other than a glaring conflict of interest? How could Laurence, not to mention The New York Times, ever agree to such a thing?

To present-day journalists, the answers seem obvious. Of course Laurence’s Manhattan Project assignment was a clear conflict of interest. But on closer scrutiny, the issues become hazier, and the answers more complicated and ambiguous.

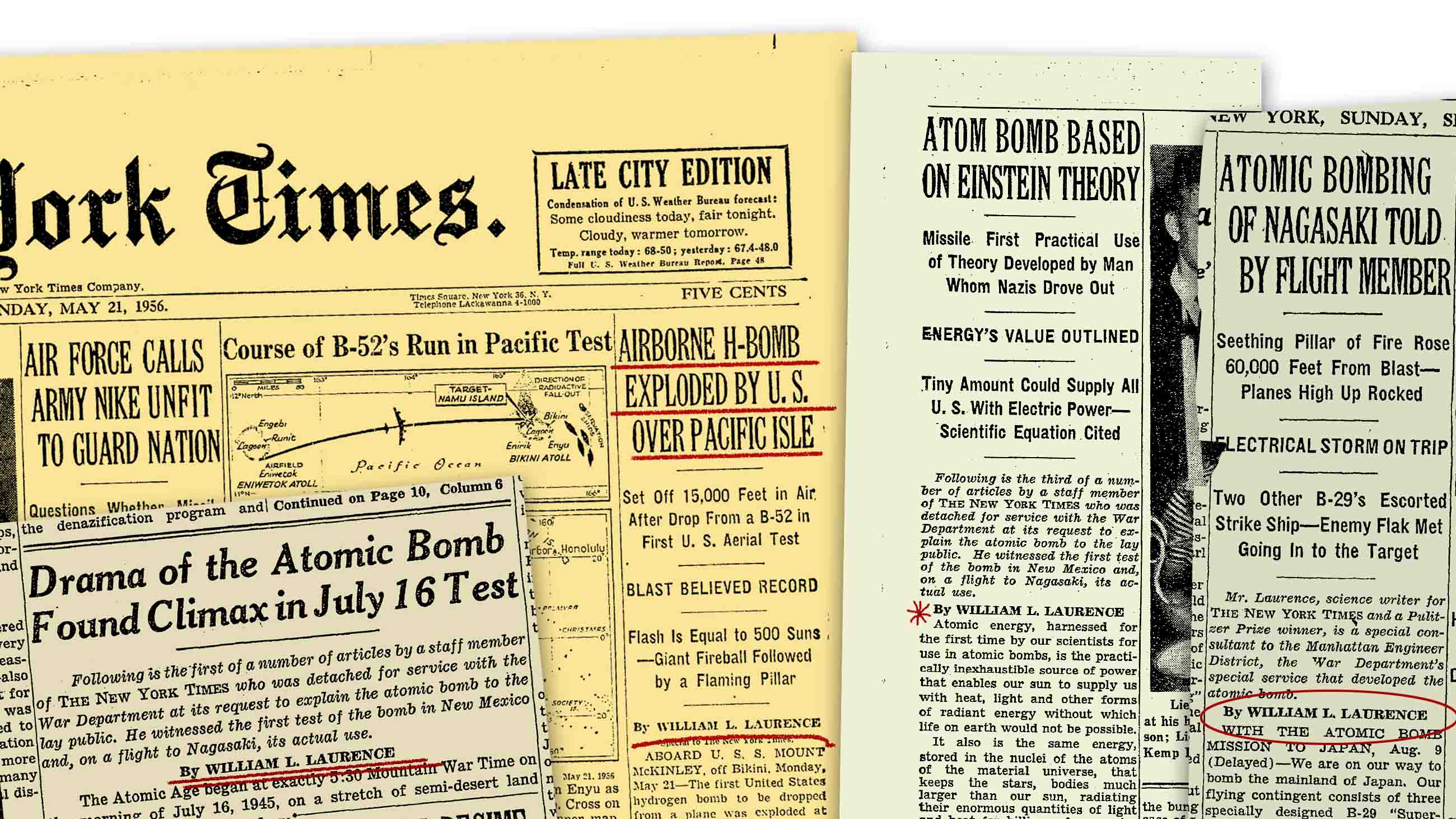

Laurence won his second Pulitzer Prize in 1946 for his Manhattan Project reporting, specifically his eyewitness account of the Nagasaki bombing mission. In 2004, the progressive journalists Amy and David Goodman called for the prize to be revoked, charging that Laurence had knowingly covered up the effects of radiation sickness on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors by “parroting the government line” that such reports were Japanese propaganda. That same year, Beverly Ann Deepe Keever, a University of Hawaii journalism professor, took The Times itself to task, claiming in her book “News Zero: The New York Times and the Bomb” that beginning with Laurence and continuing throughout the Atomic Age, the paper had “omitted or obscured the defining — and harmful — effect” of radiation and radioactivity and had “aided the U.S. government at critical moments in implementing an information policy that covered up or minimized the scope and impacts of radiation and radioactivity.”

However, there’s an important perspective that such accusations overlook. Laurence’s role within the Manhattan Project was a clear conflict of interest by today’s standards. But those standards were not those of a nation in a savage war for its own survival and of civilization.

For Laurence, a naturalized American citizen born in a small Lithuanian village, it all made perfect sense. He had served his adopted country in World War I as an enlisted dogface, and had been eagerly searching for a way to do so again. “While I was away with the atomic project for four months, I was off the Times payroll,” he explained in his Columbia oral history interview. “My salary came from the Army. … All the facts, all the news I got, I got from the Army and not from my connection with the Times.” If he was touting the official line and saying what the Powers That Be wanted him to say, he believed that was his patriotic duty in wartime.

Visual courtesy of the Patricia Cox Owen Collection, Atomic Heritage Foundation.

Despite Laurence’s claims, the question of just who was paying him while he was lost in “Atomland-on-Mars,” as he called it, remains unclear. His temporary boss, Gen. Leslie Groves — the military head of the Manhattan Project and the man who plucked Laurence away from the Times after personally selecting him for his atomic job — later wrote in his own memoir that “it seemed desirable for security reasons, as well as easier for the employer [i.e., The Times], to have Laurence continue on the payroll of the New York Times, but with his expenses to be covered by the MED” — the Manhattan Engineering District, i.e. Manhattan Project.

Remembering the era decades later, Gelb argued, “It wasn’t a conflict of interest because [Laurence] divorced himself from the Times. In his mind he understood that he was on leave. The Times itself didn’t know what he was doing. They knew he was on some kind of a major assignment, they knew he was going as a journalist, but they didn’t know all the details.”

Such perspectives are conveniently overlooked by those who accuse Laurence of shameless propagandizing. “We were fighting a war for survival,” said Gelb, who joined The Times as a copyboy in 1944. “You have to remember the times. And people now try to rewrite history when they talk about Laurence as a villain. No one thought of Laurence as a villain; that’s ridiculous. He was a hero. … If you could understand the emotions that went on during that war, and the fear in this country about what was going on. The whole world was crazy.” Moreover, Gelb went on, Laurence “knew he was going to be the historian of the bomb, and he took the assignment as the greatest journalistic assignment you possibly can be given.”

Gordin, the Princeton historian, also stresses the context of the times. “For me the standard has always been: was this considered unethical in 1945 when he did it? Certainly he did some reporting that no one else who was not embedded with Groves’ outfit could have, such as riding on the planes over Nagasaki. I am sure it colored his reporting … but it was still news that no one else had, and if he hadn’t reported it, no one would have.”

But what about after the war? Laurence’s own attitudes evolved slowly, fitfully, from his initial awe at the potential of the atom to drive ships around the world or power great cities on just a couple of pounds of uranium, to his dread at the prospect of Hitler acquiring the Bomb, to his self-described “constant state of bewilderment” during his Manhattan Project odyssey, culminating in his ringside seat at Nagasaki. But by the time he witnessed his fourth atomic bomb in 1946, the Baker shot of Operation Crossroads in the Pacific, he had no lingering doubts about the threat posed to humanity by the Bomb.

“Unless some means are found for its control,” he wrote in The Times, “it will inevitably lead to the destruction of civilization.” The Bomb was “not just another weapon against which our military will find a defense, but the greatest cataclysmic force ever released on earth.” And if the nations of the world didn’t quickly devise and implement a solid plan to control that force, “then the world will be living on borrowed time.”

Yet 10 years later, by the time Laurence began to express his post-Cherokee epiphany that nuclear weapons were the guarantors of peace and civilization, eerie echoes of Pentagon rhetoric had crept into Laurence’s words. His “Atomic Bill” sobriquet no longer seemed to be merely a useful way to distinguish him from his similarly named counterpart on the Times’ political desk, William H. Lawrence (“Political Bill” or “Non-Atomic Bill”). Now it seemed to indicate an actual affinity and enthusiasm for the subject.

His glowing paeans to the limitless future of atomic energy and the relative “safety” of the supposedly “clean” hydrogen weapons then under development — along with a thinly veiled disdain toward the growing grassroots campaign to ban atomic testing — only helped to enhance his image as a journalist who not only accepted but actively supported the Bomb as a part of 20th-century civilization. Let other reporters issue dire warnings about the dangers of the malevolent isotopic byproducts of atmospheric testing settling into the bones and thyroids of innocent children. For Laurence, the atomic umbrella of our nuclear stockpiles would protect us all from harm while the scientists continued to harness the peaceful atom for the benefit of mankind.

Such remarks were uncomfortably close to the official line of the Pentagon and the atomic weapons laboratories, not to mention atom boosters like Edward Teller, Lewis Strauss, and Gen. Curtis LeMay, leader of the Strategic Air Command. Which made it easy to see why some people seemed to think Laurence was espousing the same viewpoints not out of honest conviction but because he was still beholden to the authorities.

I was beginning to come around to that viewpoint myself until I obtained FBI files on Laurence through the Freedom of Information Act, which tell a different story. Far from parroting the Pentagon and the Atomic Energy Commission, Laurence was causing them consternation by possibly revealing secret technical data on the H-bomb in the pages of The New York Times on at least two separate occasions — consternation acute enough that more than once, AEC officials asked the FBI to investigate Laurence for possible charges of espionage.

On April 2, 1954, The Times published a Laurence piece headlined “Pacific Bomb Tests Hurled Man Into the Hydrogen Age,” detailing technical breakthroughs that were bringing the hydrogen bomb from its unwieldy beginnings as a clumsy industrial-sized apparatus powered by supercooled liquid fuel to a “dry weapon,” a smaller, more practical device deliverable by aircraft — work that culminated in the Cherokee device that would later awe him so. According to a declassified internal memo, AEC commissioners at a meeting three days later “agreed that this article was a serious disclosure of classified information and that it should be immediately referred to the FBI as a violation of the Atomic Energy Act.” The AEC’s general manager, Kenneth Nichols, promptly wrote to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover requesting an investigation: From whom had Laurence received his information?

Strauss, the AEC chairman, a paranoid and prickly man then engaged in destroying his archenemy, J. Robert Oppenheimer, personally interviewed Laurence a week after the article appeared. Laurence assured Strauss that “the article was based on his own deductions from reading available scientific publications and recent newspaper publicity,” and that “there were no leaks of classified information involved.” The FBI decided not to pursue the matter, its officials noting that Laurence was savvy enough to make accurate, informed speculations, especially “if we assume that he has maintained contact with scientists and public information officers of the AEC and other agencies who could give him sufficient tips by which he could verify his deductions without actually revealing to him any specific ‘Restricted Data.’” Not to mention that “a considerable number of persons had knowledge of the data disclosed,” some of which had also turned up in a Time magazine article published 10 days after Laurence’s. “Investigations in the past concerning similar disclosures have demonstrated the futility of such investigations,” noted the bureau, adding that “here is another example of ‘leaks’ to the Press, which is illustrative of the fact that the solution of the problem is a tighter security control within the agencies involved and not through investigations by this Bureau.”

A couple of years later, after Laurence’s Cherokee experience, a similar dust-up occurred over Laurence’s “H-Bomb Improved by Fall-out Curb” in The New York Times of July 29, 1956. The FBI again concluded that there was “insufficient evidence” to warrant an investigation and that the information in the article could be the result of “educated speculation.”

“For nearly an hour after the fireball had faded I watched incredulously the great many-colored cloud that had been born in a gigantic pillar of fire,” Laurence wrote in his 1959 book “Men and Atoms.”

Yet the signs of Laurence’s philosophical conversion were also evident. In the 1956 piece, extolling H-bomb design improvements that were supposed to greatly reduce fallout, Laurence noted that “by eliminating the weapon’s most repugnant element, the multimegaton fusion bomb has thus been ‘humanized’ to the point where it becomes a large concentrated conventional weapon. As such it becomes a greater deterrent against aggression than ever before, since it removes the strongest objection against its possible use as a defense against an aggressor.”

That Laurence’s dogged enthusiasms occasionally aroused official alarm does not, of course, disprove his critics’ assertions that he was co-opted by the government. But neither is it consistent with the profile of a journalist sold out to the atomic establishment. The charge that he discounted the effects of radiation and fallout in Hiroshima and Nagasaki overlooks the fact that many scientists at the time did so too. Keever details the case of an Australian journalist, Wilfred Burchett, who became the first Allied reporter to visit Hiroshima after the Bomb and wrote articles on a mysterious “atomic plague” affecting the survivors, reports later dismissed by U.S. authorities as propaganda.

Laurence had flown over Japan after Hiroshima to get a look at things from the air, and was in fact slated for a later visit after Nagasaki to get an on-the-ground view for himself, but was instead literally pulled off the airplane minutes before its departure and ordered back to the States and The New York Times — possibly because General Groves wanted to make sure that his star reporter would stay on the reservation and not say too much if he got a personal look at the devastation and the ravaged survivors. (One reason Groves had chosen Laurence for the job to begin with was that it would enable him to keep a leash on the reporter as the project reached fruition, rather than reveal too much with his public articles and speculations, as he’d been doing several years previously. As Laurence himself once joked, Groves realized he would either have to hire him or shoot him.)

There’s no doubt that Groves and the military were consciously attempting to downplay the dangers of radiation. If Laurence never got to see post-bomb Hiroshima, he did get back to the site of the Trinity test along with other reporters in an official tour hosted by Groves himself in early September 1945. Even as Laurence and the other visitors were required to wear canvas booties over their shoes — as Groves explained, to keep any residual radioactive sand from sticking to their soles — the general denied the stories of a mystery illness affecting A-bomb survivors and claimed that “any deaths from gamma rays were due to those emitted during the explosion, not to the radiations present afterward.” Laurence dutifully reported it all.

Laurence certainly knew enough about the physics of the Bomb to know that radiation was a unique danger. But was he intentionally trying to mislead his readers? Wellerstein, the nuclear historian, doesn’t think so. In his blog Restricted Data, he wrote that Oppenheimer and many others told Laurence that “radiation was not such a big deal, that anyone who was affected by radiation would already probably have been killed by the blast and thermal effects of the bomb. They were wrong, we now know. But the U.S. atomic experts didn’t figure that out until after they had sent their own scientists to Japan in the immediate postwar. … I don’t really think we can fault Laurence for not knowing more than the best experts available to him at that time.”

Ultimately, Laurence made a judgment call that journalists today must also make for themselves, whether they’re war correspondents embedded with the U.S. military in a combat zone or science reporters given exclusive access to potentially revolutionary biomedical research. There is a line dividing journalistic independence from the compromises that are sometimes necessary to obtain access to guarded areas where vital stories may lurk, but the line is seldom bright or fixed in place. Journalists must define it for themselves, just as William Laurence did, for better or worse.

In a 2009 Nature editorial, “Science journalism: Too close for comfort,” Boyce Rensberger called Laurence’s era the “Gee-Whiz Age” of science journalism, in contrast to the “Watchdog Age” that began in the early sixties, as writers such as Rachel Carson began to question the accepted wisdom that everything science brought us was wonderful and benign. After Watergate, many science reporters went all in on the watchdog role, striving for exposés about corporate malfeasance and scientific fraud.

While the “Atomic Bill” nickname was well earned, Laurence was also an enthusiastic reporter and investigator on medical subjects, with a special interest in cancer cures and other intractable medical issues. One morning in 1941, he had what seemed a profound insight for a possible cancer treatment and was so inspired that he actually published it in Science. One of his biggest stories after World War II was on the discovery of cortisone to treat rheumatoid arthritis, for which he not only won a Lasker Award but even met with President Harry S. Truman to propose an expedition to Africa to secure the plants needed for cortisone synthesis. Whatever else one might think of Laurence, he was not content to sit in the newsroom and churn out watered-down rewrites of press releases and scientific papers. And that was actually a problem: Laurence began to believe his own press, often considering himself more of an expert than the experts, more qualified to dispense wisdom and advice than those who were actually charged with doing so. His Columbia interviews are laced with rants against the establishment, against the common wisdom of science, in ways that can prefigure the 21st-century conspiracy theorists and ideologues who accuse corporations and the government of suppressing cancer cures or clean energy.

Even though he wrote four books and hundreds of news articles during his career, Laurence apparently left behind no papers, diaries, journals, notebooks, or any of the other records that would be expected of a professional writer.

“I see as the future role for the competent science reporter,” said Laurence, “that he is the only one who has the opportunity to stand from a height, as it were, and see a lot of fields, get an overall sort of bird’s eye view of what is going on, and … act as a catalyst, one who can fertilize like a bee – taking a pollen here and planting it there to fertilize ideas.” It was “not enough for a science reporter to record a certain development of science. He must also have a sense of social consciousness, a sense of social awareness.” That social consciousness infused Laurence’s writing about the power of the atom — from his early fears that it could bring victory to the Nazis, to the apocalyptic warning that it could destroy civilization, to the beatific view that it could “transform the earth into a paradise of plenty.”

We will probably never know the true extent to which William Laurence was co-opted, compromised, or corrupted by his military and governmental connections and involvements. It appears that in many ways, he was never really certain himself, and allowed himself to fall into a rabbit hole of murky motivations, ethical conflicts, and questionable alliances for the sake of what he viewed as his journalistic duty and dedication to the truth. What is clear, however, is that he allowed his awe, his sense of wonder, to overwhelm his consciousness, numbing his original visceral dread of atomic weapons and his detailed knowledge of their power. After struggling for decades with the insoluble conflict between the atom’s potential for both unparalleled good and unspeakable evil, he resolved the struggle in his own soul by surrendering to a comforting anodyne, a conviction that nuclear weapons were ultimately a “world-covering, protective umbrella” to shield humanity until the dawn of a golden era of peace.

Blinded by the fireball light of Cherokee that shone so brilliantly and then faded, Laurence anesthetized the dread he had felt and warned of long before any of his colleagues by simply fooling himself. Those of us who are his inheritors must guard against falling into the same trap.

Mark Wolverton is a science writer, author, and playwright whose articles have appeared in Undark, Wired, Scientific American, Popular Science, Air & Space Smithsonian, and American Heritage, among other publications. His most recent book is “A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” In 2016-17 he was a Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Is there anything as beautiful in the Universe as the explosion of a nuclear device?

A forgotten figure of no little importance in the Manhattan Project. Thanks for filling the gap.

Really, really nice article, Mark.