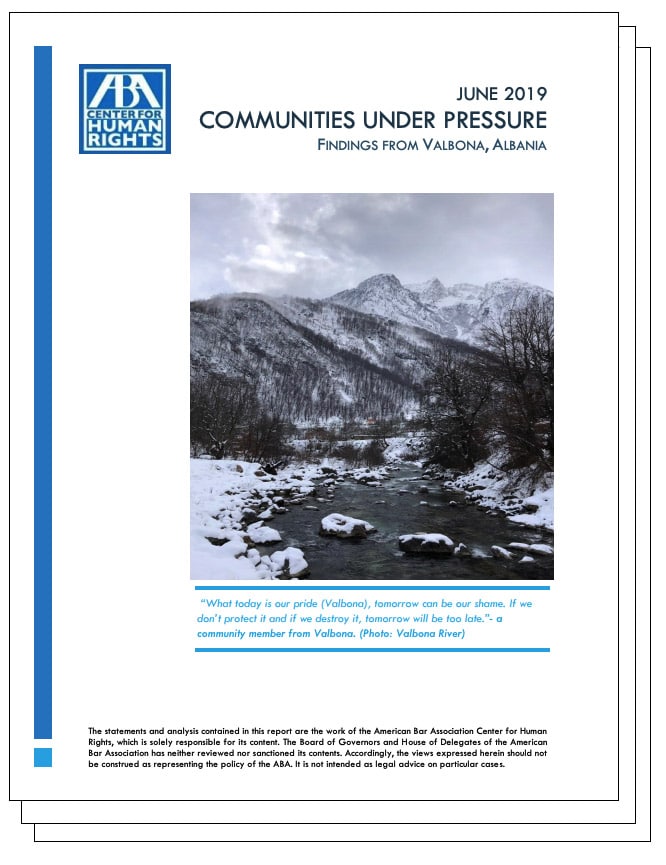

Of CNN, Hydropower, and Albania’s Valbona Valley

In February 2018, an Albanian construction and engineering conglomerate, Gener2, announced that it was expanding its portfolio of infrastructure, telecommunications, and energy projects to dip its toe in media. In a deal brokered with Atlanta-based news giant CNN, Albanians would now have access to the country’s first CNN affiliate news channel, called A2 CNN. The channel began broadcasting in December, with the CNN logo stationed prominently on its website and broadcasts.

What viewers might not know when looking at that CNN logo is that just one month before the deal was announced Gener2 had sued a tiny activist organization, along with its director, in a remote valley in the Albanian Alps. At the time, Gener2 was constructing at least two hydropower projects in Valbona Valley National Park, a 31-square-mile preserve in the heart of the Albanian Alps, inspiring fierce opposition from locals. In response the company, one of Albania’s largest, sued the organization for defamation, seeking 20 million lek (around $180,000) in damages.

A court dismissed the lawsuit, and it currently languishes in appeal. But activists and international observers argue that the legal filing was part of a broader pattern of intimidation and harassment carried out by Gener2, its representatives, and government officials against local opponents of the hydropower project.

Drawing on more than two dozen interviews, an American Bar Association human rights report suggests that backers of hydropower projects in Albania are harassing and threatening locals.

Those and other allegations were corroborated in June in a lengthy report from the American Bar Association Center for Human Rights. Drawing on more than two dozen interviews, the report details extensive allegations of harassment and threats in Valbona. It also documents a physical attack against a member of a team of Albanian journalists sent to cover the hydropower project construction.

Gener2 vigorously denies that it has harassed activists, and, in a statement emailed to Undark, the company insisted that opposition to its work in Valbona comes from “an extremely small number of the local population.”

Albania, along with other countries in Europe’s Balkan region, is turning extensively to hydropower as an engine to grow its economy. Critics, meanwhile, say these projects are often marred by corruption, lack of oversight, and a dearth of input from local residents who are unfamiliar with the full environmental and economic tradeoffs. These competing perspectives provide the backdrop for the union between CNN, one of the globe’s most trusted news brands, and an Albanian conglomerate that has a clear stake in continuing Eastern Europe’s hydropower boom.

Asked whether the news channel had any concerns about the allegations against Gener2, Dan Faulks, the vice president of communications for CNN International Commercial, which handles sales operations of CNN properties outside the U.S., deflected.

“We feel that your query relates directly to Gener2 rather than A2 as our affiliate,” Faulks wrote in an email to Undark, “and I’m pleased you’re in contact with them directly.”

The Valbona Valley sits in the mountains of northern Albania, near the country’s border with Montenegro. Small-scale agriculture is an important part of the economy, and access to basic services, like electricity, can be irregular. Although Albania has experienced periods of rapid economic growth since the fall of communism and the political turbulence of the 1990s, it remains one of the poorest and most rural countries in Europe, with a per capita GDP comparable to Indonesia or Venezuela.

As Undark reported in 2017, there has been a boom in hydropower development in Albania and other parts of the Balkans — a development that, supporters say, will bring much-needed income and electricity to the region. But this has also spurred concerns among locals, environmentalists, and corporate watchdog groups, who are worried about a lack of local input on projects, as well as threats to farmers and wild rivers.

Igor Vejnovic, the hydropower coordinator at Bankwatch, an organization that monitors public funding in Eastern and Central Europe, said he has seen a recent surge in hydropower development in Bosnia, Macedonia, and Albania, but little oversight of those projects. “These are also countries that have weak environmental governance,” Vejnovic said. “Basically, institutions are not working well on permitting this kind of infrastructure, and also monitoring later when it’s built.”

Vejnovic, who has done research on the Valbona projects, described it as “an iconic kind of case” of how hydropower development can go wrong. The hydropower projects, he said, are “just pouring this concrete into the rivers without really having a second thought about whether this is something that this region actually needs.

“Is the benefit going to locals at all?” he asked. “Or is it actually ruining their livelihoods, in a way, because Valbona is also developing sustainable tourism?” Vejnovic said that hydropower projects employ very few locals after the construction ends, and that, while the power they produce feeds into national or regional grids, it does not necessarily result in reliable local power.

Many Valbona residents have expressed skepticism about the project, as well as fears about how it may affect their livelihoods. Catherine Bohne, an American who moved to the region in 2009 and speaks fluent Albanian, has been a leader in these efforts — in part, she says, because her English skills and political savvy allow her to navigate bureaucratic processes that are daunting to many residents of the area. In 2016, Bohne and other residents formed TOKA, a conservation organization that opposes the hydropower projects.

Since 2016, TOKA and Gener2 have engaged in a dizzying array of lawsuits and countersuits over the hydropower projects. TOKA has also sued the government for failing to prevent construction that, they argue, is illegal under the country’s environmental and construction permitting laws. Bohne has spoken about the project before the European Union, and TOKA has received support from Bankwatch, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and other international NGOs. In late June, TOKA filed a formal complaint with the Energy Community, an international organization that governs the energy market in the E.U. and its neighbors, alleging that Gener2 did not do proper environmental assessments for the project.

According to Bohne, Gener2 barely consulted with Valbona residents before beginning construction. What little consultation that existed, Bohne says, was a sham. One public meeting yielded a list of 20 signatures in support of the project — but, “of those 20 people, two were dead at the time,” Bohne says. “Everybody else on the signatures are employees of the construction company.”

Citing ongoing legal action, Gener2’s chief business development officer, Gëzim Pani, declined to speak on the phone, but he did send lengthy responses from the company to a list of questions, describing himself as “very passionate about the development of the economy and the energy sector in the country.”

In those responses, Gener2 said that the company did hold consultations with locals, even though it was not legally required to do so. “The process of public consultation that we undertook at our own initiative, was mostly done as part of our social responsibility,” Gener2 said. The hydropower projects will increase electricity production for Albania, create jobs in the region, and improve local infrastructure, they added.

In January, the ABA Center for Human Rights sent an independent consultant, South African human rights attorney Sally Hurt, to Valbona to investigate these and other claims. The organization’s final report details dozens of allegations, including that police threatened peaceful protestors with arrest; that an employee of a Gener2 subsidiary made similar threats; that locals who oppose the hydropower projects have been hit with suspicious administrative fines; and that some opponents of the project have received veiled threats.

Last July, Endrit Habilaj, an Albanian television journalist, was filming at a construction site when security guards contracted by Gener2 approached him and his crew, physically attacking one of them. According to the ABA Center for Human Rights report, another person reported being physically attacked by people connected to the company.

These incidents can have a chilling effect on opposition. “One of the things that was very clear in each of the focus groups, and interacting on an individual level with people living in Valbona Valley, was how much pride they take in their heritage, and how resilient they are,” Hurt told Undark. “I think it’s important to highlight that, because it links to something that became quite clear as well, which was the impact of quote-unquote low-level harassment, and how much of a cumulative impact it has not only on individuals, but on the fabric of a community.”

Gener2 says that allegations that it is pressuring activists are “absolutely false.” Asked about the attack on Habilaj, Gener2 responded that it was “very regretful and an isolated event” and that “Gener2 does not sanction violent acts and has nothing to do with what happened,” adding that it has since trained staff and subcontractors in conflict avoidance.

The report also classifies the lawsuit against Bohne as a possible attempt at intimidation. “I think it’s a SLAPP,” Bohne said, short for “strategic lawsuit against public participation” — a common but dubious legal tactic used to silence protestors that is widely denounced by free-speech advocates. Hurt, the consultant and human rights lawyer, agreed. “I think it certainly is, or could have the effect, of a SLAPP,” she said. “And so it does appear to be one.” For its part, Gener2 denies this, and the company said they were “left with no choice but to use the legal means at our disposal to protect our image, our people, our work and resolve the conflict.”

Shortly after Gener2 filed its suit against Bohne and TOKA when a friend got in touch to ask if she had heard the news: The company was about to expand into media, after signing on with CNN. A press release shows Gener2’s CEO shaking hands with Greg Beitchman, vice president of content sales and partnerships for CNN International Commercial.

In the 1980s, CNN began to develop an international network of news affiliates. Ingrid Volkmer, a media studies scholar at the University of Melbourne who researched CNN’s growing global reach throughout the 1990s, said the network was originally a way for CNN to source stories in countries where it might not have reporters. But, Volkmer said, the network quickly became a way for CNN to spread its methods of doing journalism, hosting conferences in Atlanta and building connections around the world.

Perhaps necessarily, those international partnerships involved diverse kinds of media organizations. “I noticed already back then that some of the companies that were affiliated with the world report program were not necessarily just broadcasters,” Volkmer said. Other affiliated organizations, she added, were in authoritarian countries that might not protect freedom of speech. Recently, CNN has received criticism for its partnerships in Turkey — where the CNN affiliate is owned by a close ally of the country’s increasingly authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Today, CNN has more than 300 affiliate organizations around the world. Some of these partnerships are simple licensing contracts that permit the outlets to share some content. In a handful of countries, including Greece and the Philippines, affiliates are full-fledged CNN stations, subject to the same editorial standards as CNN itself and going by names like “CNN Greece.”

The partnership with Gener2 falls somewhere in between these two poles. A2 CNN can use the CNN brand and refer to itself as CNN’s “exclusive affiliate” in Albania. CNN’s consultants also helped the station launch its operation — but A2 is not necessarily subject to CNN’s reporting standards.

For people familiar with the region’s media and politics, though, the lines between Gener2, A2, and CNN might not seem so clear-cut. “Normally the television [stations] are just linked to the business, with the business owners, and these are ways of the business owners to influence the public opinion and influence the politics in Albania,” said Rea Nepravishta, an environmental advocate in Tirana who is active with TOKA.

“CNN itself has a bit of a political weight,” said Vejnovic, the Bankwatch staffer. He mentioned that CNN only has a few other affiliates in the Balkans. “There is a lot of political implications going with it, that you have the U.S. backing, in a way.”

Sally Hurt, the South African attorney, asked a related set of questions. “I think coming from CNN’s context as an American organization, or media outlet, perhaps separation of business entities is something very clear for them,” she said. “But is the same understanding held in Albania, by your average Albanian citizen?”

CNN’s Dan Faulks dismissed such concerns. “I would remind you that A2 is not a CNN channel but rather an exclusive affiliate in Albania, and that we are not aware of any allegations regarding A2’s coverage or the channel being used for influence,” he wrote. And in its email statement, Gener2 emphasized that its “construction activities have no relationship with A2 News.”

In an email to Undark, Kristian Mucaj, the media coordinator for A2, stressed that the organization is “independent from other Gener2 businesses.” The station also has not covered the hydropower controversies, Mucaj said — in Valbona or anywhere else.

For some observers of the Albanian media landscape, the whole situation looks familiar, and not especially surprising. Besar Likmeta is the Albania editor for the Balkans Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), and he oversees Reporter.al, a news site that has been covering the Valbona issue for years.

“I wouldn’t say that their investment in Valbona has been transparent, that they’re respecting community rights,” Likmeta said, based on his impressions from Reporter.al’s coverage. “How does this reflect on the TV station? I don’t know,” he continued. “I mean, most of the media in Albania are owned by corporations, companies like Gener2, that have interest in other fields and tend to use the media to pull their political or economic interests. So, they are not standing out from the crowd. The market is like that.”

Likmeta’s organization recently included A2 on a list of Albanian media organizations selling airtime to politicians. The practice, Likmeta said, was fairly standard, and A2 had seemed to take the criticism from BIRN seriously. The channel, he stressed, was still pretty new — it remains to be seen what kind of work they’ll produce.

For now, despite TOKA’s opposition and, Bohne says, court-ordered work stoppages, construction is continuing on the hydropower plants. For advocates like Bohne and Nepravishta, the stakes feel higher than a hydropower project.

“Local people are gaining nothing, the environment is being destroyed, their social fabric is being destroyed, and only the most powerful are gaining from it,” Nepravishta said, summarizing her reasons for opposing the hydropower. “So, to me, why I have been involved in this cause is because symbolically, the Valbona cause, it represents this kind of struggle. It’s a battle of the old Albania with new post-Albania that changed, only in 30 years — that changed so much.”

Michael Schulson is an American freelance writer covering science, religion, technology, and ethics. He writes the Matters of Fact and Tracker columns for Undark.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I think you have noted some very interesting points , regards for the post.

We don’t want the Goddamn hydro centrals. It’s all beneficial to the corrupt Albanian politicians that fill their pockets with money from these companies and on the other hand close an eye while they massacre our beautiful nature. These hydro centrals are feeding the rest of Europe with energy anyway, it’s not meant for the locals. It’s time to cleanse Albania of this corruption that’s affecting it from the roots, and it’s been embedded for a long time in our system.

Taking ads for pols isn’t exceptional; taking questions from press and deferring to an affiliate or rejecting PSAs in favor of paid ads in a climate like Albania’s is corrupt. They shouldn’t be taken by an ‘incumbent’ to right of way rules that are deferential to that entity rather than EC and public process. Rural electrification has been bad enough in the USA. Nice tag. (Better than ‘Renewables, WCGW!’)