Interview: Uncertainty, Science, and Public Health Communication

For Charlotte Dries, a Ph.D. student at the Harding Center for Risk Literacy at the University of Potsdam in Germany, the problem of misinformation was personal. “During the pandemic, I had in my social circle some people who were starting to believe in conspiracy theories and misinformation, and I wanted to do something about it,” she said.

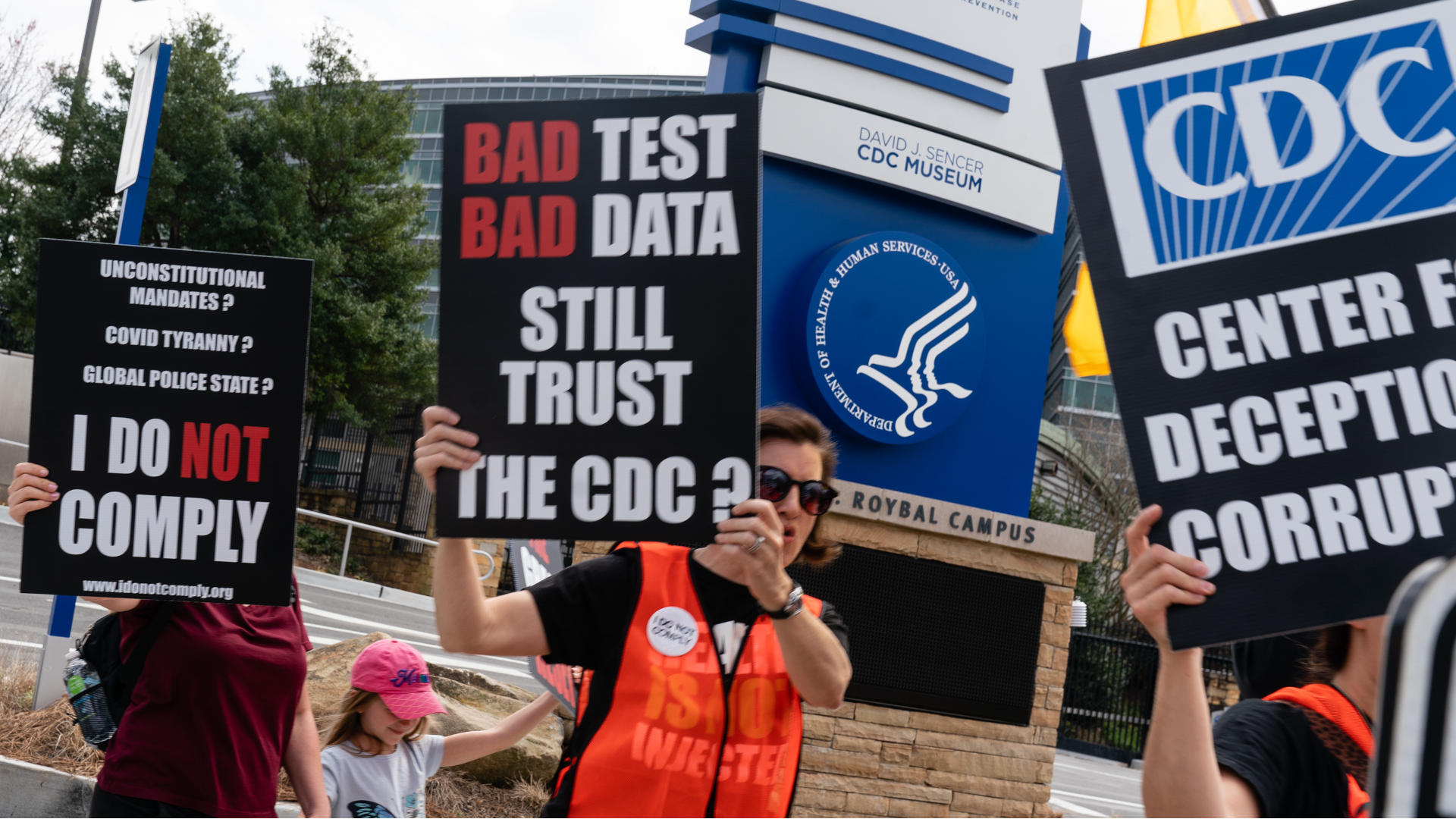

Part of the problem, it seemed, was public health messaging itself. Too often, some experts have argued, scientists and decision makers withheld uncertainties in the data on Covid and its myriad potential interventions, and overstated their confidence. When evidence shifted, public trust waned. Dries seeks to understand whether simply admitting, when relevant, that the science is unclear — regardless of the crisis at hand — is a better strategy.

Researcher Charlotte Dries is interested in how people perceive scientific uncertainty. Her recent study concludes that explaining uncertainty doesn’t erode trust — rather it helps maintain trust if evidence changes.

Visual: Courtesy of Charlotte Dries

“I really focus on uncertainty communication around scientific evidence, and how people perceive it,” she said. “So, when you communicate uncertainty, do they find it trustworthy or not? And how do they perceive the communicator? Do they then trust the communicator? Do they find the communicator competent?”

Dries and her colleagues tested this in an online experiment in which 800 participants were given variations on a fictitious statement from a public health authority stating that there was no apparent link between a new Covid-19 vaccine (called CraVAX in the study) and heart muscle inflammation. In some instances, the statement was unequivocal and communicated no uncertainty. In others, uncertainty was offered without any explanation, or by attributing it to the small number of people who had thus far received CraVAX. A fourth instance communicated uncertainty in the finding because tracking patient outcomes was messy.

When participants were later presented with new evidence showing that the earlier statement was incorrect, Dries and her colleagues measured their reactions — including any shifts in perceptions of the health authority.

The results, published earlier this year in the journal Public Understanding of Science, were pretty straightforward: “Communicating uncertainty buffers against a loss of trust when evidence changes,” Dries and her colleagues concluded. “Moreover, explaining uncertainty does not appear to harm trust.”

I spoke with Dries by Zoom and email. Our conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Undark: What prompted you and your team to investigate the way scientists communicate uncertainty?

Charlotte Dries: We saw that there’s a need of communicating uncertainty during the pandemic, because there was a lot of over-claiming; evidence coming from the scientific community to the public, and uncertainties were left out. And evidence was kind of distorted. People were getting irritated because evidence was changing, and guidelines and communications were changing, and they didn’t understand why that is. We also witnessed that there was irritation, and also maybe a little bit of loss of trust. And we were thinking, how can we tackle this loss of trust?

UD: Is it accurate to say that your main finding was that scientists should be up-front about any uncertainties in their work?

CD: Yes. In general, scientists should communicate uncertainties, for legal reasons, ethical reasons, and practical reasons. People need to be informed, and to make decisions on their own. So, I think this is also a responsibility of the scientific community. But what we found in our study is that it can also help mitigate a loss of trust, when you communicate uncertainty up-front. The aim shouldn’t be to maintain trust in science, but rather to be trustworthy.

UD: Can you say a bit more about the distinction between trust and trustworthiness?

CD: Trustworthiness is a property of the communicator, whereas placing trust in someone is an act of the audience. A communicator can signal trustworthiness for instance by being transparent about uncertainties. But whether people will value this trustworthy communication and place trust in the communicator is a different story. In our study, we found that people indeed trusted the communicator more if they communicated and explained uncertainty upfront and the communicated evidence turned out to be wrong later.

UD: During the Covid-19 pandemic, public health messages changed as new data became available, which sometimes led to public confusion and distrust. Could some of that loss of trust have been prevented, if scientists had been more forthcoming about what they didn’t know?

CD: I think this sounds reasonable — it could be — but I can’t say this from my study in particular, because my study is just an online study with a very artificial setup. But I think if you are being upfront, if you are setting the expectation that evidence can change, people may be less disappointed when guidelines change later on. And people may not think that the communicators were incompetent, or that they were dishonest, because they were explaining or communicating it from the very beginning, that this could happen.

UD: Is there a danger that being too open about uncertainties could actually exacerbate public anxiety and skepticism, rather than building trust?

CD: This is a real danger. Indeed, the science historian Naomi Oreskes and her colleagues have shown how a number of actors have strategically used uncertainty information to sow distrust in the scientific evidence around prominent policy debates such as climate change. But I would not conclude from this that some uncertainties should not be communicated. Quite the contrary: It is an ethical responsibility of the scientific community to be transparent about what we don’t know and why. And going back to our study, if uncertainty is not communicated at the outset and the evidence changes later, this may have negative long-term effects on trust.

I would also like to return to the distinction between trust and trustworthiness. Our goal as a society should not be more trust, but rather more trustworthiness. For trust is only valuable when placed in trustworthy agents, but harmful when placed in untrustworthy agents, as the philosopher Onora O’Neill has put it. So, I think it is more useful to ask how the scientific community can be more trustworthy, and one answer to that is to be open about what we don’t know.

UD: Reports such as those put out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are sometimes met with skepticism due to the uncertainties in the models being used. With that in mind, do you have any advice or suggestions for scientists to have to talk to the public about climate change?

CD: You should communicate uncertainties, because, as I said, there are ethical reasons to do so; and also because, in the long run, if it turns out to be wrong, it may worsen. But the way you should communicate uncertainty depends, I think. There’s also this concept, again from Onora O’Neill, who has thought of “intelligent openness”: You should communicate in a way that is understandable for people, and you should communicate in a way that is also usable for people. I think you can also apply this to uncertainty communication: If the uncertainty information is not usable for people, and they don’t know what the scientist means by it, what this means for their life, then you shouldn’t overburden the public. And, third, you should also communicate such that it is accessible, so that people — if they are interested — then they can check what you are saying, and what uncertainties there were, and how did you come to the conclusions, and what are the limitations?

UD: In the study that you published, your sample was predominantly young, educated, and internet-literate people. Do you have to do more research to see if your findings apply to the population at large?

CD: Yes, definitely. And we’re actually also planning a study, with a representative sample, in Germany; and also, I think it is important to look at different subgroups. So, which particular people find uncertainty communication trustworthy, and which don’t, because not everyone perceives uncertainty communication equally.

UD: Could cultural differences impact how uncertainty communication is perceived? Were there any indicators about that in your study? Or is this just something that requires further research?

CD: I think this requires further research. There’s this concept of “WEIRD” countries — especially in psychology, we only look at WEIRD countries — Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. So, I think it would be interesting also to look at different countries.

UD: Are there other possible cultural factors that you’d like to investigate?

CD: Rather than cultural factors, we are currently focusing on differences between individuals. Why do some people find uncertainty communication trustworthy, while others do not? For example, people’s epistemic beliefs about uncertainty in science may play a role, and these may vary across cultures. We have also just examined how people’s prior beliefs on topics such as climate change or Covid-19 vaccines influence how they perceive the communication of uncertainty around these topics. Knowing who doesn’t value uncertainty communication, and more importantly, knowing why, can provide important insights for science communication.

UD: Can you imagine a scenario where public health officials shouldn’t mention some of their uncertainties in order to achieve a particular health outcome? Or is full transparency always the best bet?

CD: I think this is a question of values. What is more important to you — is it important to inform people and to empower people? Or is it more important to save lives, for instance, and get most people vaccinated?

UD: What role does the media play in communicating scientific uncertainty, or for that matter, public officials? I’m wondering if your findings might apply beyond just scientists.

CD: People have different expectations for journalists than scientists. For scientists, you have the expectation that they need to be competent, and that what they’re saying is correct. And for journalists, I think, especially, it’s very important that they are transparent and don’t distort things. But — this is just a personal anecdote — I think many scientists, when I talk to them, they are afraid to talk to the media, because they’re afraid that their scientific findings may be put in the wrong light, or that they might over-claim something. And that’s why, if they communicate too many uncertainties, then they might be perceived as non-credible.