Charles Darwin never left Britain again after his famous five-year voyage on the Beagle. He was chronically ill and created his transformative works of science from the comfort of his home and gardens, with his children drawing in his notes and helping with experiments. “The way he worked looked nothing like the professional men of science of that time. Yet he met with incredible success,” Erin Zimmerman notes in her recent memoir, “Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood and the Fight to Save an Old Science.”

BOOK REVIEW — “Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood, and the Fight to Save an Old Science,” by Erin Zimmerman (Melville House, 272 pages).

Darwin may seem an odd focus for a book about the experiences of modern women who work in natural history, but he existed at an important turning point. Botanist and suffragist Lydia Becker, who began corresponding with Darwin in the 1860s, saw the potential for him to be an inspiration. After Becker had been rejected from Manchester’s scientific societies because of her evidence-based arguments that women were not intellectually inferior to men, she began a local scientific society for women. She spoke to these women about what Darwin accomplished from home, suggesting they could do the same.

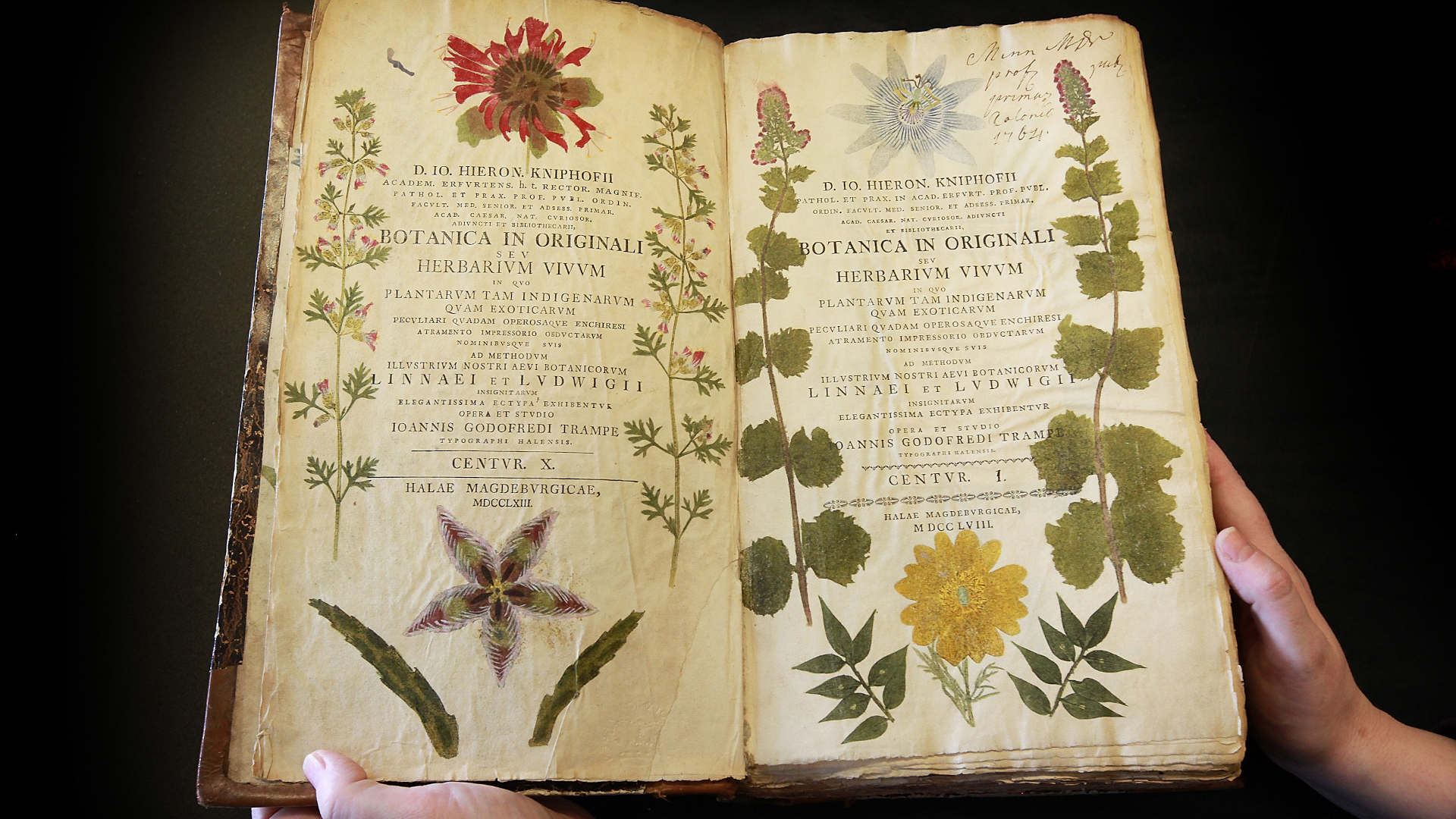

Women of means in Europe and the United States, including Becker, dominated botany in its earliest history. At this inflection point in the mid-1800s, men attempted to professionalize and “defeminize” the field, Zimmerman writes, moving science from the home into the laboratory and intentionally marginalizing women. The structures and expectations that came to define science workplaces were created at that time. Zimmerman uses this example to show how her experience as a 21st-century botanist is still influenced by these structures, at the same time that natural history — the foundation of all biological sciences — is on the decline. For women in the field, it’s a double whammy.

Zimmerman ultimately left botany and became a science writer, and her experience is an example of a much larger phenomenon: Women leave science in droves, and natural history scholars are becoming as endangered as the rare species that their work identifies and catalogs. As she puts it: “The most astounding thing about taxonomy as a science is the yawning gap between how crucial it is to the enterprise of human knowledge and how valued it is in practice.”

According to “Unrooted,” between 1988 and 2010, more than half of the top 50 most-funded universities ended their botany programs. The recent announcement that Duke University will close its flagship herbarium, which was met with intense backlash from the international research community, makes this stark reality especially apparent. Although the herbarium — which opened in 1921 and is one of the largest collections of plants, algae, and fungi in the country — is not mentioned in Zimmerman’s memoir and she doesn’t have a direct connection to Duke, the timing of that closure with her book’s release couldn’t be more apt.

Zimmerman ultimately left botany and became a science writer, and her experience is an example of a much larger phenomenon: Women leave science in droves.

The life of a botanist hasn’t always been so grim for Zimmerman. She delighted in her early work. In the plant anatomy lab where she first trained as an undergraduate, researchers “spent the bulk of their day working alongside the students and technicians,” she writes, and “everyone seemed happy and relaxed.” But it was a vestige from another time, run by two longtime tenured botanists. That experience gave her “a very skewed idea of what being a scientist in the competitive, often underfunded rush of the twenty-first century looked like,” adding later, ”It was a place I would always be trying to find again.” That longing is a theme throughout the book.

Zimmerman describes the incredible experiences she had during her dissertation work: a stint with scanning electron microscopy at the world-renowned Kew Gardens in the United Kingdom; an adventurous plant collections trip to Guyana, where she scaled steep rock faces and rainforest trees for plants of all sorts, especially on the lookout for a group of early-diverging legumes that she studied; and genetics and microscopy study at the Montreal Botanical Garden. During this phase, she also pondered motherhood, well aware that many of these research experiences were not set up for people with children. Indeed, 43 percent of women in science leave research or take part-time roles after having their first child; just 23 percent of men do the same. Zimmerman’s longtime partner, Eric, did want children, and it’s clear from the questions she asked herself and her colleagues that, despite her initial trepidation, she did as well.

As her Ph.D. work drew to a close, Zimmerman repeatedly heard that funding for both postdocs and natural history research was scarce. “I was crestfallen,” she writes. “It seemed like everything I loved most in science belonged to an earlier time.”

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Newly married to Eric and with a baby on the way, and after a disheartening six-month job search, Zimmerman was thrilled to land a postdoctoral position at a government research facility near her childhood home in Ontario. Although her new boss seemed supportive, Zimmerman felt increasingly isolated from her colleagues, both during pregnancy and after returning to work following her parental leave. She endured comments about her “brain fog” and her lack of dedication to the field. Despite the fact that she was a new mom who was in pain and physically exhausted, her mentor pushed her to work more. In one particularly egregious moment, Zimmerman had to pump breast milk in a rarely used shower, where she wondered: “How had I once been worth six figures in doctoral scholarship money but now wasn’t worth a clean pumping space?” Overworked and unsupported, Zimmerman left her research career. On the decision to leave academia, she writes: “Staring down the barrel of a decade of short-term contract appointments at the same time you need to be starting your family would and does make even the most dedicated scientist think twice.”

Zimmerman deftly weaves the personal essays in her book into the larger history of botany. What I learned from Zimmerman is that this career shift — one that I made too, from plant biology to science writing — is a pattern that has played out since botany’s professionalization in the 19th century. In 1848 when Becker was marginalized from the field, she published a book that brought her expertise to everyone, “Botany for Novices.” Similarly, Arabella Buckley, another correspondent of Darwin, pivoted to writing children’s books, such as “The Fairy-Land of Science.” These women took advantage of a boom in publishing, and were among the writers who launched the age of popular science.

According to “Unrooted,” between 1988 and 2010, more than half of the top 50 most-funded universities ended their botany programs.

Women scientists continue this tradition today. Zimmerman joins a cadre of plant biology memoirists who write vividly about their personal experiences in 21st-century science, and how those experiences connect to social problems. In the New York Times bestseller “Lab Girl,” Hope Jahren writes about the job precarity of her longtime collaborator and lab manager, Bill Hagopian. In “Braiding Sweetgrass,” Robin Wall Kimmerer calls for a reciprocal relationship with nature. Lauren Oakes’s “In Search of the Canary Tree” highlights the need to incorporate social science and oral history collections into scientific work about environmental loss. These works also provide a uniquely personal view into modern research life, rare moments of candidness and intimacy that general audiences rarely get from scientists. Who knew that these authors were following in Becker’s and Buckley’s footsteps — keeping up a long tradition envisioning a more inclusive science?

Writing also gave Zimmerman an outlet to share science with everyone. She writes, “At a moment when I felt excluded myself, I could choose to be an active part of including others.”

Natural history is incredibly popular — life on Earth is fascinating and fun. And yet, Zimmerman’s experience shows how people can be drawn into the field by these interests, and then let down by the exclusionary culture. Zimmerman provides a rare window into the inner life of a new mom in biology research. Although she nods to many solutions about how funding and incentives could be changed, she does not explore how they might be accomplished.

Zimmerman deftly weaves the personal essays in her book into the larger history of botany

Bearing witness to this loss is a huge and welcome feat in and of itself, and a short book such as this one cannot be expected to thoroughly solve such wicked problems. But in the same way that Zimmerman reaches back in history, the book would have benefited from greater depth on who is creating cultural change in science today. The push by postdocs to unionize at some institutions, for example, is not mentioned at all.

Stories about quitting science can easily bog down in negativity. Zimmerman avoids this pitfall beautifully, never losing sight of her enthusiasm and gratitude for her good experiences in science. In a scene near the end of the book, Zimmerman brightly describes joining a group of mostly women volunteering to help digitize plant collections. In her version, it was an example of the inclusiveness of citizen science, but I couldn’t help feeling a pang of rage. Experts like Zimmerman are out there, consistently impeded from passing on their knowledge or contributing to their field. I can attest that many of them volunteer their time to other scientists’ work.

As Darwin’s story shows, science has often been advanced by people working outside the hallowed halls of the ivory tower. Many people working to save our collective knowledge of natural history before it’s lost are left doing just that, on their own time. Professional science was set up to exclude people; the movement toward a more inclusive science can rectify historical and contemporary wrongs.

Katie L. Burke is an award-winning features editor and science journalist. She is a senior contributing editor at American Scientist.

Sad to read that botany and natural history are on the decline at major universities. I’m an adjunct biology instructor at a liberal arts college, and a freelance science writer. For the past five and a half years I wrote a monthly column on nature and wildlife for The Boston Globe. My column focused mainly on the natural history of plant and animal species in the greater Boston area, and included stories about natural history related research and conservation projects by scientists such as Richard Primack from Boston University, Bryan Windmiller from Zoo New England, and Wayne Petersen from Mass Audubon. Sadly, my column was cut a few months ago. I guess writing isn’t always a safe refuge for biologists who want to write about natural history.