“Anything I need to be aware of?” Clyde Thompson considered the question and tapped out a reply.

“Probably,” he began.

It was December 20, 2016, six weeks since Donald Trump had been elected president.

The political winds that had shifted so unexpectedly on Election Day were starting to blow through the headquarters of federal agencies throughout Washington, D.C., including the stately Beaux-Arts structure jutting out onto the National Mall that housed the U.S. Department of Agriculture. News reports suggested the new administration was preparing to populate some of those offices, from Interior to Energy, with fossil fuel industry boosters. Trump’s transition teams were already asking for lists of agency employees who worked on climate change. Career staffers were left guessing what new directives might be coming their way.

This article has been excerpted and adapted from “Gaslight: The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Fight for America’s Energy Future,” by Jonathan Mingle. Copyright © 2024 by Jonathan Mingle. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Those winds had reached Thompson in Elkins, West Virginia, where he was completing his 15th year as supervisor of the Monongahela National Forest — and contemplating the time-sensitive email from his boss’s boss, Glenn Casamassa, then associate deputy chief of the U.S. Forest Service.

Casamassa had a call scheduled that afternoon with his own superior at the Department of Agriculture. On the agenda: the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

The pipeline was slated to cut a 21-mile swath through the Monongahela and George Washington National Forests in West Virginia and Virginia. A few days earlier, Casamassa had been visited by executives from one of the biggest gas and power utility companies in the country, Dominion Energy, who wanted the Forest Service to “sync up” its permitting timetable for their proposed pipeline with those of other federal agencies. Their concern: Clyde Thompson and his staff were holding things up.

Now Casamassa wanted Thompson, the Forest Service’s lead contact for the ACP on behalf of both forests, to bring him up to speed.

Thompson and his team had spent nearly two years studying Dominion’s construction plans for laying its 42-inch-wide conduit through some of the most flood- and erosion-prone topography in the U.S. After all that scrutiny, he explained, they were still worried that the risks of burying the pipeline in that terrain were far greater than the company’s executives and engineers seemed to appreciate.

When Kent Karriker, an ecosystems specialist who worked under Thompson, first saw a map of Dominion’s proposed route, his jaw had dropped in disbelief. Many had grades well over 40 percent — so steep you needed to grab hold of a tree to haul yourself up them. Some were more like cliffs than slopes: Construction crews would have to secure their excavators to trees or bedrock with long cables and then lower them on winches. In some spots, workers would have to daisy-chain those winches together, one machine to the next, in a kind of excavator garland draping the mountainside.

Thompson, Karriker, and their colleagues had pressed Dominion for months to provide detailed designs for those stomach-churning inclines, laying out precisely how it would stabilize the soil both during and after digging.

Because they were still waiting for that information, Thompson explained to Casamassa, the Forest Service had filed a letter in the official record stating that its final decision date on issuing a special use permit to ACP LLC was “To Be Determined.”

That did not sit well with Dominion vice president of pipeline construction Leslie Hartz. She seemed to think, Thompson wrote, that she could go up the hierarchy and negotiate a faster timetable directly with Casamassa or his superiors. But Thompson had told her that the rules were not “discretionary” — they couldn’t just be waved away. There was a process they were legally required to go through. That, he explained, was why Hartz was “upset.”

No one had ever built a pipeline this big across that kind of terrain before. The stakes of getting this right were high.

Thompson reminded Casamassa that the goal of all their efforts was to demonstrate that they “have a reasonable chance of keeping the pipeline on the mountain and keep the mountain on the mountain.”

Based on the expert analyses he had seen so far, he concluded: “I’m not optimistic.”

Back in the spring of 2014, Clyde Thompson had learned about the Atlantic Coast Pipeline the same way most people had: He read about it in the newspaper. Unlike most people, however, Thompson oversaw the management of a million acres of public land.

Tall and lean, with gray hair and a deeply lined face, Clyde Thompson had the affable, unflappable, wearily competent demeanor of a veteran administrator. He had been supervisor of the Monongahela since 2002, a length of tenure in one forest that was rare for an agency where administrators tended to be bounced around the country as they climbed the bureaucracy’s ladder and pay scales.

Over the years, Thompson had dealt with all kinds of projects and fielded demands from plenty of stakeholders with strong opinions on how the “Land of Many Uses” — as the national forest tagline goes — should be used, from logging interests to hikers, hunters to conservation groups. And energy companies.

Based on the expert analyses Clyde Thompson had seen so far, he concluded: “I’m not optimistic.”

Thompson was surprised Dominion hadn’t reached out sooner. He would have liked a heads-up — a letter, a call, an email. Something. When Dominion finally did contact his office and he saw a map of its proposed route, he immediately saw problems.

“They couldn’t have picked a worse place than that first route,” Thompson said.

Karriker, who had spent more than a decade at the Monongahela, had the same reaction. “They came to us with essentially a straight line drawn across the national forest,” he said, “like they laid a ruler on the map.”

Things went downhill from there. Because of the concern about erosion and landslides, Dominion was required to analyze soils at representative sites along the route. Thompson’s staff repeatedly asked to see the qualifications of the subcontractors performing those surveys. A West Virginia–based Dominion lobbyist named Bob Orndorff pledged that they would provide a list of resumes before selecting them. When Dominion finally submitted that list — after the contractors had already gone out and dug pits in the forest — only one person named on it turned out to be a licensed soil scientist. But she told the Forest Service she had never been hired by Dominion. The people Dominion did hire had little expertise in soil analyses — rendering the surveys largely useless.

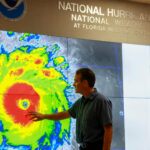

Clyde Thompson, pictured here in 2018, was the supervisor of Monongahela National Forest when the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was first proposed. When Dominion finally contacted his office with a map of its proposed route, he immediately saw problems.

For Thompson and his team, this strange bit of deception signaled a troubling willingness to cut corners. Dominion had submitted its route without carefully studying the soil and rock it would be disturbing along the way. This struck them as completely backward: They thought that what they learned from soil surveys should inform the development of the safest route for the pipeline. “We were on edge because of that,” said Karriker.

Meanwhile, Karriker tried to communicate another concern: The pipeline route would likely pose unacceptable (i.e., illegal) risks to the habitat of threatened and endangered species. He and his colleagues made it clear that Dominion would have to avoid both Cheat Mountain — the only known home to the eponymous Cheat Mountain salamander — and Shenandoah Mountain in the George Washington National Forest, home to the Cow Knob salamander, which likewise was found nowhere else in the world outside of its narrow ridgetop.

Karriker was bemused by the way that Dominion’s representatives never really addressed the points he raised but simply waved them away. “It was like that scene in ‘Star Wars,’ with Obi-Wan saying, ‘These aren’t the drones you’re looking for,’” he said. “That continued for a year and a half.”

They finally got Dominion’s attention with a letter on January 19, 2016, in which the Forest Service formally rejected the proposed route because it “did not meet minimum requirements” of laws protecting endangered species and mitigating environmental damage.

The letter brought things to a screeching halt. Without a permit to cross the forests, Dominion had a major problem on its hands. The company scrambled to submit a new route. That one jogged about 15 miles farther south, but the Forest Service noted that it “only partially addressed the problems while creating new ones.” When Dominion filed yet another, longer alternative route the next month, it went through areas that the company had previously rejected as too steep and hazardous.

“The elephant in the room throughout all of this is that you’re going to do this really serious earth-disturbing construction going straight up the side of the mountain,” Karriker said. “Gravity and water are uncompromising forces. There’s just not much way to get across the central Appalachians west to east without encountering those kinds of problems.”

“It was like that scene in ‘Star Wars,’ with Obi-Wan saying, ‘These aren’t the drones you’re looking for.’”

And Dominion wanted to traverse some literally dizzying terrain. At one spot on Cloverlick Mountain in Pocahontas County, the grade exceeded 100 percent — so steep that Karriker was sick for two days after the exertion of hiking up it to inspect its soils and survey pits dug by Dominion’s contractors.

“Some of these are so steep they are hard to stand on,” Thompson told me. “You start digging in them and you hit a seep of water that works like lubricant on soil. You start thinking, ‘How do you hold it? How do you keep it on the ground?’”

Veterans of West Virginia’s highlands, Thompson and Karriker worried most about the confluence of steep grades and heavy rains. Monsoonal torrents regularly visited the Allegheny Mountains. As runoff percolated into the disturbed soil around the pipe, where would it go?

“Some of those places — I just don’t see how you do it,” Thompson said. “I wouldn’t want to build my house there. I’d be worried every time it rained.”

On June 23, 2016, rain started falling early in the morning across the mountains of central West Virginia and didn’t stop for 12 hours.

A series of powerful thunderstorms moving east from the Ohio Valley, brimming with moisture from the Great Lakes, had parked themselves over the basins of the Elk, Gauley, and Greenbrier Rivers — not far from the ACP’s route. Some towns received nearly 10 inches of rain and were partly submerged. Rivers surged to record-high levels. When the waters receded, hundreds of homes had been wrecked or washed away. The damage from one summer day’s thunderstorms totaled more than a billion dollars. Twenty-three people died in the floods.

It was the third-deadliest flood in the state’s history and, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service, a “thousand-year event.” While the volume of rain was unusual, the flooding was not. Heavy rains are the deadliest natural hazard that West Virginians face. Each of West Virginia’s 55 counties reported at least 14 floods in the quarter century preceding the 2016 floods. Since 1967, every county in the state has been declared a federal flood disaster area at least once, several as many as 10 times.

“Gravity and water are uncompromising forces. There’s just not much way to get across the central Appalachians west to east without encountering those kinds of problems.”

Torrential downpours have increased in intensity nationwide over the past several decades. Climate scientists are confident they will only become more severe as our world warms. For each degree Celsius of warming, the atmosphere holds around 7 percent more water vapor — providing fuel for more powerful storms. In a 2017 report, the Army Corps of Engineers forecast that the largest increases in rainfall and stream flows would happen in West Virginia — specifically, in those areas that the ACP would traverse. In fact, the region is already experiencing this shift: According to NOAA, extreme precipitation events have increased 55 percent since 1958.

The June storms triggered hundreds of landslides throughout West Virginia. Clyde Thompson sent out teams to inspect damage in the Monongahela. They found roads partially buried by slides or with gaping holes in them, exposing metal culverts and drainage pipes. Entire hillsides had given way, leaving scars hundreds of feet long and exposing bedrock. Staffers came across 48 landslides just while conducting random post-flood checks, without even looking for them.

Engineers like to design for maximum stress, balancing cost with the need to withstand unlikely but extreme impacts. “From my perspective, it’s like designing a campground for a Fourth of July crowd,” said Thompson. But he thought Dominion wasn’t even designing for the normal range of possible rainfall events that Central Appalachia saw in a typical year, let alone the supercharged storms of the future.

“I never felt like we got to the point where they were designing it for today’s weather, for normal fluctuations,” said Thompson.

Climate change hadn’t even entered the analysis.

Five months later, Donald Trump was elected president. In early 2017, his new political appointees at the U.S. Department of Agriculture signaled to their Forest Service subordinates their preference for a more accommodating approach to Dominion’s requests. Before long, Thompson’s team lost any meaningful influence over the planning of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline through public lands they managed. The detailed steep slope designs would never become part of federal agencies’ analysis of the project’s risks because Dominion would never submit them — and the Forest Service stopped asking for them. This sudden, post-election about-face from the Forest Service removed the last real obstacle for ACP’s planners to move through the national forests.

But Karriker and Thompson knew that terrain. They had stewarded it for decades. And they worried that, eventually, reality would catch up with the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

Jonathan Mingle is a freelance journalist and the author of “Fire and Ice: Soot, Solidarity, and Survival on the Roof of the World.” His latest book is “Gaslight: The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Fight for America’s Energy Future.” His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, Yale Environment 360, Inside Climate News, The Boston Globe, Slate, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.