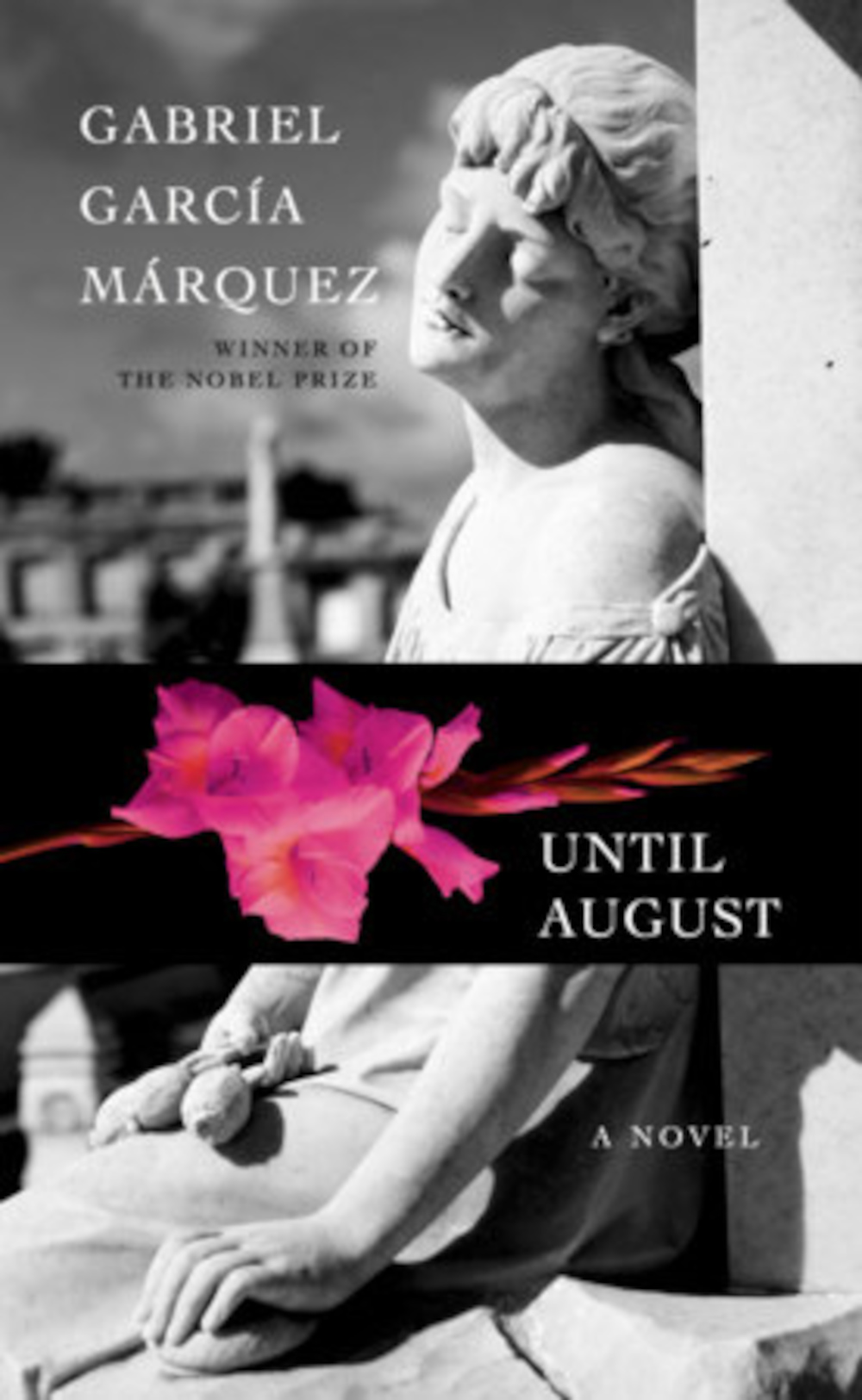

In March, the sons of Gabriel García Márquez, the Nobel Prize-winning Colombian writer, published a posthumous novel against the specific wishes their father expressed before he died in 2014 at the age of 87. García Márquez had struggled through several versions of the book as dementia set in, and, perhaps stung by uncharacteristic negative reviews from his previous novel, didn’t want the new one published.

“Until August,” the story of a woman who travels to her mother’s grave once a year and takes a new lover on each visit, got mixed reviews. Some were outright harsh. In The New York Times, Michael Greenberg wrote “It would be hard to imagine a more unsatisfying goodbye.” García Márquez’s decline, he continued, “seems to have been steep enough to prevent him from holding together the kind of imagined world that the writing of fiction demands.”

“Until August” by Gabriel García Márquez (Knopf, 144 pages).

Wendy Mitchell, who was an administrator with England’s National Health Service until her diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in 2014, recalled the moment she learned of the publication plans last year. “I type every day for fear of dementia snatching away that creative skill, which I see as my escape from dementia,” she wrote last October in The Guardian. “Maybe Márquez thought the same?”

The novel’s publication raises some vital questions about living with an aging and perhaps ailing brain. What do mild cognitive impairment and dementia do to our creativity? How do these conditions affect our ability to use words, formulate sentences, and craft stories?

Neuroscientists have been exploring these questions for several decades. First, a few definitions. People with mild cognitive impairment have lost more of their cognitive functioning than others their age, and often struggle to remember things. But they’re capable of managing daily activities like dressing, eating, bathing, and finding their way around. In dementia, cognitive difficulties have increased enough to interfere with daily life, and personality changes are more likely.

García Márquez isn’t the first literary giant whose later work raised questions about the impact of dementia on creativity and language. Nearly 20 years ago, neurologist Peter Garrard of St. George’s University of London delved into the mind of the novelist Iris Murdoch, who won the Booker Prize, the U.K.’s equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, in 1978.

Garrard wanted to see how Murdoch’s use of language changed, specifically word frequency and word length, so he ran three of her novels through a computer program: her debut 1954 novel, “Under the Net’’; “The Sea, The Sea” (the book that won her the Booker Prize), published in 1978; and her final novel, “Jackson’s Dilemma,” published in 1995, four years before her death. He also compared the complexity of Murdoch’s syntax (how she structured language) across these three works.

Garrard and his colleagues published this analysis in the journal Brain in 2005. They found “clear-cut lexical changes” they wrote of her final book, “without obvious effects on the grammatical properties of the text.” In other words, Murdoch used fewer words, and repeated them more often, while her syntax barely changed.

But sentence length changed dramatically. In the opening paragraph of “The Sea, The Sea,” the average sentence length was 15.6 words, while in her last book it had fallen to 8.6 words. The second, mid-career book was longer with a greater variety of words and more people than her first book, presumably as Murdoch’s confidence as a writer increased. The final book showed a precipitous drop in length and word variety, and had more dialogue and less narrative than either of its predecessors.

García Márquez isn’t the first literary giant whose later work raised questions about the impact of dementia on creativity and language.

García Márquez’s writing style changed as well, according to neuropsychologist Katya Rascovsky at the University of Pennsylvania, who compared the first 20 pages of the author’s most famous book, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” with the first 20 pages of “Until August.” Of the first book, she says, “It’s like how many words can you put into a sentence, you know? And it’s like the perfect word.” His new novel is simpler, she found: shorter sentences, less complex words, and more word repetitions.

From the very start, there’s a difference, she said. The opening sentence of “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” translated from its original Spanish, reads: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” The opening of “Until August,” in contrast: “She returned to the island on Friday, August 16, on the three o’clock ferry.”

Murdoch’s writing also flattened towards the end, according to Garrard. For example, her final novel has a character who is writing a book about a philosopher. “Murdoch, being a philosopher herself, would have used that as an opportunity to write about the work of that philosopher,” said Garrard. But she didn’t; she just said the character was writing a book. Garrard also pointed out that the novel employed a less sophisticated vocabulary and had some basic inconsistencies, alongside many simplifications.

As with García Márquez’s last book, critics were harsh on Murdoch’s “Jackson’s Dilemma.” Novelist and literary critic Hugo Barnacle wrote in The Independent that it “never begins to make the remotest kind of sense.”

Garrard’s close analysis of Murdoch caught the eye of Janet Cohen Sherman, clinical director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychology Assessment Center and associate professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School. “I was intrigued by the fact that he was looking to see if he could see changes through the course of her writing,” she said.

Sherman and her colleagues have been researching ways to distinguish normal cognitive aging from mild cognitive impairment. (It’s worth noting here that not all people with mild cognitive impairment will go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease.) They’ve been working on a test that considers the ability to process information: Volunteers were asked to repeat sentences that were read to them, one at a time. The sentences were all the same length, but varied in their complexity. “What you’re doing when you’re listening to somebody, even a sentence, is you’re actively processing that information,” she said. Notably, Sherman added, “if you can’t process the information well, you’re going to struggle to repeat the sentence correctly.”

Ambiguous sentences, no matter the length, proved to be problems for some people with mild cognitive impairment. “If you hear a sentence like ‘The electrician repaired his equipment,’” Sherman says, “it could be that the electrician repaired his own equipment. Or maybe he repaired somebody else’s equipment.” But non-ambiguous sentences such as “The babysitter emptied the bottle and prepared the formula” were easy to repeat back.

Sherman and her colleagues also found that in people with mild cognitive impairment, semantics (the meaning of language) and memory are independent — meaning someone with mild cognitive impairment trying to tell a story could struggle for the right word or phrase but might easily remember an image or a feeling. Or they may have the words ready but not remember the details of a storyline.

Oddly enough, García Márquez himself once described the loss of semantic memory in an exquisitely accurate way, Rascovsky said. At one point in “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” people in the fictional town were hit by a plague of insomnia that resulted in memory loss that very closely paralleled what Rascovsky sees in some of her patients with frontotemporal lobe dementia. “The most devastating symptom of it was a loss of the names and meaning of things,” she said.

“Remarkably,” she and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco wrote in a paper in Brain, “García Márquez created a striking literary depiction of collective semantic dementia before the syndrome was recognized in neurology.”

The townspeople first lost their earliest memories (the opposite of the usual sequence in Alzheimer’s disease). Then they lost the names and meanings of things – what’s called representational knowledge.

They then started writing notes and attaching them to things: “This is the cow. She must be milked every morning so that she will produce milk, and the milk must be boiled in order to be mixed with coffee to make coffee and milk.”

“Remarkably, García Márquez created a striking literary depiction of collective semantic dementia before the syndrome was recognized in neurology.”

García Márquez evidently had some insight into his own situation. His sons wrote in the preface to “Until August” that their father’s late-in-life dementia was “a source of desperate frustration for him.”

In “Until August,” Rascovsky detected clear signs that the author was struggling. “What made me a little bit sad,” she said, “wasn’t necessarily the simplicity of the story or the characters, but the loss of the sensory experience.” In earlier works, an orange wasn’t simply an orange. García Márquez would provide lush descriptions of its color, its aroma, and the childhood memories it evoked. Not so in his final book.

“When you think about the dissolution of semantic networks,” Rascovsky said, it makes sense “that he would have more difficulty coming up with those concepts and linking them together.”

In the end, Rascovsky said the novel is still “much better than any of us could ever do. But it is not what we’re used to for García Márquez.”

Joanne Silberner writes about global health, mental health, medical research, and climate change. Her work has appeared on NPR and in STAT, Discover, Global Health Now, and the BMJ, among other publications.