Why Parents Are Turning to a Controversial Treatment for Food Allergies

For families with food allergies, micro-managing daily life to avoid accidentally consuming the wrong food can be a huge burden. They scour labels. They avoid restaurants. They ban their kids from birthday parties, or refuse to enter sports stadiums, worrying that peanut shells littering the ground could trigger life-ending anaphylaxis.

The resulting angst has driven some families and physicians to try a therapy that has done well in early studies but has unclear long-term effects and is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The controversial treatment is called oral immunotherapy (OIT). Conceptually, the method works like allergy shots, which for 100 years have reliably treated pollen and other environmental allergies by desensitizing the immune response to these triggers. Instead of injecting allergens through the skin, OIT involves consuming a bit of the forbidden food each day, at gradually increasing doses, so the immune system can learn to put up less of a fight.

Over the past decade, the number of OIT providers has grown from just a handful of doctors nationwide to a small, influential cohort of more than a hundred today. Thousands of food allergy patients who have tried oral immunotherapy in the United States and abroad swear by the treatment, often calling the results life-changing. And with an FDA decision expected by early 2020 for Aimmune Therapeutics’ “peanut capsules,” OIT could soon go mainstream.

But at the moment, allergists remain deeply divided over the treatment, which doesn’t work for everyone and carries uncertain risks. In contrast, the traditional approach — avoidance of the trigger food — achieves safety for the vast majority of individuals. In fact, someone with a food allergy has a greater chance of being murdered than dying from an allergic reaction. And yet that fact belies the hidden stress and fear that grips many of the estimated 32 million Americans with food allergies. For them, the possibility of a life-ending reaction looms large, and many are eager to see the FDA approve a drug that advocates say could put those fears to rest.

But with many researchers dismissing the science as thin and the treatment unnecessary, the schism over oral immunotherapy — among both physicians and food allergy families — may not easily resolve. “This is a very weird field,” said allergist Kari Nadeau of Stanford University School of Medicine. “I’ve been in oncology. I’ve been in autoimmune disease. And just over the past 13 years I’ve been in allergy.” There are lot of different physicians with varying levels of training, Nadeau said. “It’s a little strange to have such a divergent climate.”

Though OIT is relatively new, the science behind desensitization therapy dates back more than a century, when the term “allergy” had barely entered the medical vocabulary. In 1905, a German doctor described treating “milk idiosyncrasy” in infants by feeding incrementally increasing drops of milk. Three years later, a London physician reported giving daily doses of egg to calm a teen boy’s “egg poisoning.” By 1940, clinicians had published a total of nine papers describing the use of similar methods to treat dozens of people with allergies to milk, wheat, egg, orange, tomato, and cocoa.

In the mid-1960s, scientists discovered the molecular culprit: immune-system antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE). Each IgE recognizes a specific allergen — ragweed, say, or peanut. When the allergen gloms on, IgE travels to other immune cells, leading them to unleash histamine and other chemicals that set off an allergic reaction in the nose, lungs, throat, or skin.

Beyond these isolated advances, food allergy research got little attention for decades. This was, in part, due to the low prevalence rate. As recently as the early 1980s, less than 1 percent of people in the United States were thought to have a food allergy. “For a long time, the easy answer was just to avoid the food if you were allergic,” said Christina Ciaccio, a pediatric allergist at the University of Chicago Medicine who has consulted and helped run studies for companies developing peanut allergy treatments.

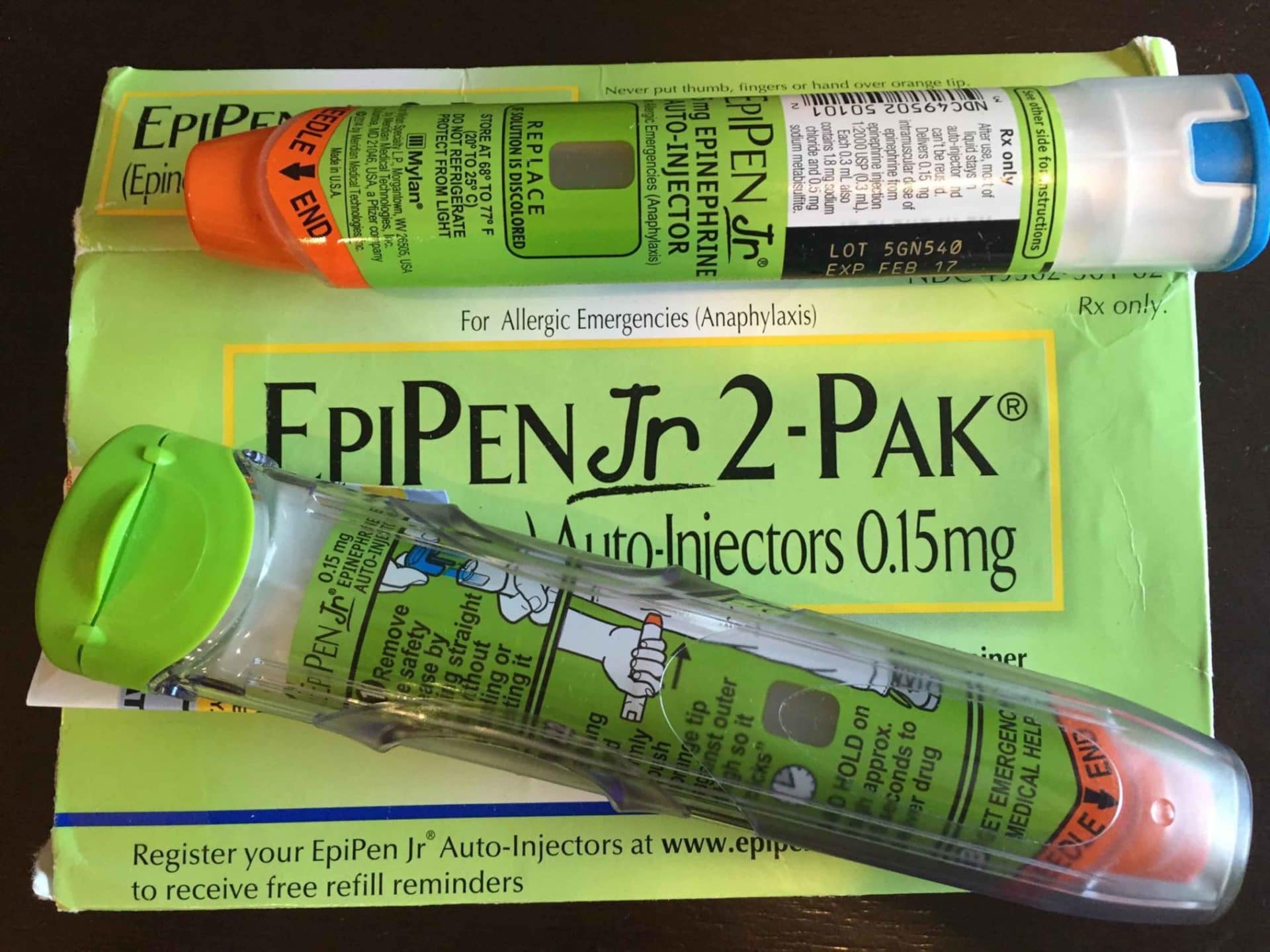

If a reaction did escalate to something more serious, such as full-body hives, throat tightness or trouble breathing, a shot of epinephrine — FDA approved as an auto-injector under the name EpiPen in 1987 — could start to bring relief within minutes. As manufacturing practices changed, Ciaccio said, people started eating more processed foods, and it became increasingly difficult to avoid accidental allergen exposures.

In the late 1980s, initial reports of anaphylactic deaths due to peanuts trickled into the medical literature. In 1992, Denver physicians published a small study in which they treated food allergy patients with skin injections, the approach routinely used for environmental allergens. But the study came to a halt when a formulation error caused a subject in the placebo group to die of anaphylaxis. “That slowed food allergy research for over a decade,” said Ciaccio.

While research stagnated, media stories brought the terror of food allergies into the public consciousness. In 1995, The Wall Street Journal ran the headline “Peanut Allergies Have Put Sufferers on Constant Alert.” Later that year, a British daily tabloid newspaper published a story titled “Nut Allergy Girl’s Terror; Girl Almost Dies from Peanut Allergy.”

In the years that followed, for reasons not well understood, food allergies became more common among U.S. children. Between 1997 and 2008, peanut allergies more than tripled. In 2002, as part of the first state guidelines for managing food allergies in schools, Massachusetts called for peanut-free lunch tables. In a span of about 15 years, peanut allergies had risen from a virtually unknown medical condition to what some might call a public health emergency. Today, food allergies affect 8 percent of kids in the U.S. and more than 10 percent of adults.

In 2005, five research centers received a National Institutes of Health grant to form a consortium to conduct basic research toward developing food allergy treatments, and to run clinical trials to test them. “We were scared to do peanut,” said A. Wesley Burks, a pediatric allergist at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and one of the consortium’s lead investigators. Evidence suggests that the vast majority of life-ending food allergic reactions are caused by peanuts or tree nuts.

So as a proof of concept, the consortium’s first oral immunotherapy studies were done with egg. Burks and colleagues conducted a study showing that daily doses of powdered egg white could help people with egg allergy. The method was not a cure. But when the study ended, most participants could tolerate enough egg protein to withstand accidental exposures. In other words, they became bite-proof.

The team then enrolled 39 people in a peanut OIT study using a similar protocol. Those who made it past the initial day consumed store-bought peanut flour — which was pre-measured and sterilized in the lab, then mixed at home into applesauce or pudding or other foods. Dosing started at 50 milligrams and went up 25 milligrams every two weeks. (A few participants had to start at a lower dose and had their increases adjusted accordingly.) Once participants could tolerate 300 milligrams of peanut protein — a little more than one peanut — they began a maintenance phase, steadily increasing their daily OIT dose up to 1800 mg over the next few years.

Nearly a quarter of the original participants ended up withdrawing from the study. Four dropped out because of allergic reactions to the therapy, and gastrointestinal or asthma symptoms. The rest withdrew for other reasons, including transportation issues, parental anxiety, and failure to perform home dosing. But among the 29 participants who finished, 27 successfully passed an oral food challenge with 3.9 grams of peanut protein (about 16 peanuts).

As that initial wave of OIT publications came out, a smattering of private-practice allergists saw an opportunity. They recognized the principles and basic procedures as similar to the allergy shots they routinely administered for airborne antigens. “Any trained allergist would know how to recognize and respond to a reaction,” said Richard Wasserman of Allergy Partners of North Texas. Whether triggered by peanut or pollen, “an allergic reaction is an allergic reaction.”

Chatting with an El Paso colleague who was among the nation’s first allergists to administer private-practice OIT, Wasserman was inspired to develop protocols for his own clinic. Wasserman started treating patients in July 2009 and he and the colleague presented their early OIT experiences in a 15-minute oral poster session at a national immunology meeting a few years later.

“The room was overflowing out the door,” Wasserman recalled. His results were eye-opening and would soon be backed up by published studies. Among individuals who try OIT, about 80 percent become bite-proof.

In such reports of preliminary results, many parents saw a potential escape from daily struggles characterized by fear, isolation, and invisibility.

Shea Tritt discovered her son’s peanut allergy when he was 13 months old. Moments after licking peanut butter off her finger, he broke out in hives, his eyes and face swelled, and his tongue got “so big he couldn’t close his mouth,” she said. From that point, “I was just so petrified of reliving that moment that I just cut off anything new,” said Tritt, a gymnastics coach in Abingdon, Virginia. Her son has never tasted an orange. “I think he kinda learned, this is what I eat, and we stayed in that really small box.”

Alicia Bales’ son is allergic to dairy, egg, some tree nuts, and some seeds. She worries about an allergic reaction, she said, but her son’s condition has affected their family in other ways, too. Last Thanksgiving, she made a batch of her grandmother’s special egg noodles with her daughter. Her son, Ethan, wanted to play with the dough. “I couldn’t let him,” said Bales. Since Ethan’s diagnosis, some foods now signal danger rather than safety, illness instead of nourishment, fear rather than comfort, Bales explained. “There’s a source of love from my past that I can’t pass on to my son.”

Families dealing with food allergies also report feeling misunderstood because people tend to lump their life-threatening condition in with a slew of other diets, health concerns, and ethical reasons for restricting certain foods. To help others understand, food allergy patients may stress that they have a “life-threatening” food allergy, Ciaccio said. “These individuals then get unfairly called out for hyperbolizing.”

Sometimes the most painful misunderstandings occur within extended families. “They’re navigating aunts and uncles, sometimes even grandparents, who don’t get it — or they get it and choose not to respect the guidelines. And so that’s another source of potential anxiety,” said Tamara Hubbard, a licensed counselor in the Chicago area who works with food allergy families and maintains a website that includes a directory of nationwide food allergy counselors.

Bales often has to remind her father-in-law about her son’s allergies, sometimes multiple times a day — explaining that dairy is found in ice cream and many baked goods, and often in chocolate. She doesn’t blame him, she said, because he didn’t grow up around food allergies. When her son first got diagnosed, Bales said, she felt as though he was playing at the edge of a cliff: “No one could see the edge except for me.”

For some, oral immunotherapy offers a sense of control. Parents want “to do something about it right now,” Bales said — even when a treatment carries a high risk of unpleasant side effects.

They hear stories and read medical reports about success with oral immunotherapy and “then they start questioning their allergist or physician: Why can’t I take it?” said Thomas Casale, chief medical advisor for operations at Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), a non-profit that helped launch Aimmune.

The answer differs vastly, depending on the physician. Some insist that OIT is still experimental and needs further study to ensure it works consistently and safely. Others contend they have enough experience treating environmental allergens to configure an approach for desensitization to foods. “Those are the two different arguments, Casale said. “There’s merit with both.”

Over the years, these two camps have grown more vocal. In 2010, researchers in the NIH-funded consortium published a commentary titled “Peanut Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) is Not Ready for Clinical Use.” On multiple occasions consortium investigators and Wasserman have taken the stage at national meetings, debating OIT’s pros and cons.

Because food allergy rates have risen dramatically in just a few decades, the divide is in part generational. “I think some people are guarding the old,” said Nadeau, who directs the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University, which has helped conduct trials of food allergy products being developed by Aimmune and DBV Technologies.

Yet OIT does carry risks. An analysis of 12 clinical trials involving Aimmune capsules or store-bought peanut flour found that people on treatment were three times as likely to go into anaphylaxis compared to those on placebo or avoidance. Some experts interpret these findings, published in The Lancet in April, to suggest OIT is more dangerous than avoiding the food. “It’s one thing to say you’re willing to take risks for a treatment that’s going to offer a cure or complete resolution of the disease,” said Corinne Keet, a pediatric allergist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “But, right now, it’s pretty clear that for most people, at least in the short term, oral immunotherapy doesn’t lead to a cure. It leads to a temporary desensitization that still carries with it a risk of ongoing reactions.”

Other doctors point to a tradeoff. When consuming a “food you’re allergic to, you’re going to have some side effects along the way. We know that. Ninety-five percent of people have side effects,” said Nadeau. But “at the end of the game, if you reach that endpoint, you can start eating food and not be worried about an accidental ingestion.”

Although oral immunotherapy can cause more frequent allergic reactions, Keet said, some families may prefer the predictability over the rarer surprise reactions that happen with avoidance.

Many experts do not consider OIT medically necessary, and very few allergists offer it. The therapy is not yet FDA approved, and has no insurance billing code, said Brian Schroer, who directs allergy and immunology at Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio. Some allergists who offer OIT have billed it as related procedures such as an oral food challenge or a drug/venom desensitization procedure.

Plus, based on a recent analysis by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, it remains unclear if OIT is cost-effective compared with avoidance. “That sort of creates the ‘haves’ versus the ‘have nots,’” said Stacey Sturner, a Chicago food allergy mom whose son completed peanut OIT as a 5-year-old in 2017. Not surprisingly, the “haves” tend to be higher-income families. “OIT has ignored large segments of the patient population who have food allergy — particularly those who are poorer or ethnic minorities,” said Keet, who sees many low-income families.

Beyond cost, there’s also time and emotional burden. A treatment that requires strict compliance and many clinic visits is a significant undertaking, “especially with two working parents and multiple kids in the house,” said Edwin Kim, a father of two food-allergic children who works as an allergist-immunologist at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Such considerations can add to the frustration many families face when they hear about OIT. On the one hand, the treatment offers hope. But for some, it is inconvenient or even inaccessible. And it doesn’t work for everyone.

But on social media, these drawbacks are sometimes overlooked. Using the #OITWorks hashtag, some families post photos of smiling kids with OIT completion certificates and bags of peanuts, or eating birthday cake for the first time. Sturner, who started the Facebook group Food Allergy Treatment Talk, said that these voices have gotten louder over time. “That loudness really turned off a lot of people,” she said, “because it felt like shouting.”

Some parents say that doctors and journalists unwittingly fuel the shouting when they use terms like “graduation” and “failure” to describe OIT outcomes. Jaelithe Judy’s son started peanut OIT two years ago at age 13 but had to stop six months later after he was diagnosed with an OIT-triggered inflammatory disease called eosinophilic esophagitis. “I make a point myself never to say that my son ‘failed’ OIT,” said the St. Louis, Missouri, mother. Rather, she frames it as the treatment failing him. Judy said she is not alone on this point. Other families that have not benefitted from the treatment also “find this ‘failure’ language troubling and discouraging to their kids.”

Much rarer than OIT successes are food allergy deaths, which also get shared heavily on Facebook and Twitter. This creates “a false illusion of extreme circumstances,” said David Stukus, a pediatric allergist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, who joined Twitter in 2013 to fight misconceptions by disseminating evidence-based information. “People read a headline and now they think that their risk has changed.”

If there were a true balance of stories, Stukus said, for each tragic death that occurs and every story shared, “we would literally have a million other stories demonstrating that someone who has peanut allergy went to school that day, went to a ballpark, or flew on an airline without any problems at all.”

Still, food allergy sufferers can find themselves in dangerous situations if needed medication isn’t available. Since last year, EpiPens have been in short supply and are not always carried by airlines — something advocates are now pushing to change.

With rising pharmaceutical interest in developing food allergy products — two of which are heading toward an FDA decision — Kim worries that a single catastrophe with off-label OIT could set back the field.

In this promotional video posted by the Alabama Allergy & Asthma Center in February, doctors and patients extoll the virtues of oral immunotherapy.

The number of providers in the United States who currently offer off-label oral immunotherapy is estimated to be around 2 percent of board-certified allergists. It’s not easy for clinics to offer a highly individualized treatment that requires considerable time, clinical space, and nursing support, Schroer said. An even bigger obstacle, he noted, is the need to produce food-based products “to essentially pharmaceutical-grade levels.” Most allergists are waiting for an FDA-approved food allergy treatment before offering the therapy in their clinics. And in the case of peanut OIT, years ago leading experts believed that securing FDA approval would require measuring peanut flour into standardized capsules so each holds precise amounts of peanut protein. Aimmune Therapeutics launched in 2011 with that mission.

“The allergists who offered OIT early on were the pioneers, who had to blaze their own trails. Aimmune is working to lay the railroad and make the journey much easier and more reliable for everyone involved,” said Alison Marquiss, a former spokesperson for the Bay Area company.

Last November the New England Journal of Medicine published results of a clinical trial of AR101, Aimmune’s investigational peanut-containing drug. According to a company press release, it is the largest phase 3 peanut allergy oral immunotherapy trial to date, with 551 participants at 66 sites in North America and Europe. (Outside of research, private practice allergists in the United States have treated more than 7,800 patients with commercial food products.)

At the end of the Aimmune study, about two-thirds of the treated group were able to tolerate peanut protein equivalent to a dose of about two peanuts. Based on those results, the company submitted a licensing application. The FDA has said it will review the application in September and make a decision by January 2020. France-based DBV Technologies is developing a different type of immunotherapy called Viaskin Peanut, which delivers peanut proteins through a skin patch, and is headed for FDA review.

Outside of clinical trials, OIT has generally only been offered by private practice allergists. But as more data have come out, academic centers have begun to explore the possibility of offering the therapy as a service to patients. Some are already doing so.

“Especially as a public institution, we have the responsibility to translate what we’ve learned from trials to best practices,” said allergist Rita Kachru of the University of California, Los Angeles, which has served as a site for DBV and Aimmune trials.

Her team still considers the treatment investigational. “We are just starting to understand the risks, the benefits, the efficacy,” Kachru said.

“If we’re writing a novel,” she added, “we’re maybe at chapter 2. But I think we’re getting a better understanding, definitely more than a few years ago.”

At any given moment, OIT conversation on Food Allergy Treatment Talk, the Facebook group Sturner started, might highlight successes, discuss challenges, or raise questions. “It’s complicated. Because the human immune system is complicated. So are our emotions,” wrote Sturner on a Friday in March when a discussion about the risks and benefits of OIT became heated. “Read the threads. Absorb the info. Do your research. Most importantly, don’t panic.”

Esther Landhuis is a California-based science journalist who writes about biomedicine and STEM diversity. Her stories have appeared in Scientific American, NPR, Nature, Quanta, and Science News for Students, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I would like to add if you do not surely have an insurance policy or perhaps you do not belong to any group insurance, you could possibly well reap the benefits of seeking the help of a health agent. Self-employed or people having medical conditions normally seek the help of any health insurance brokerage. Thanks for your article.

Thank you Dr. Landhuis for taking the time to dig thru all of this. I am not sure how many other families did you get a chance to speak with but I am glad we spoke and a snippet of Anurag’s journey made it to your article. Since we spoke, we have passed a full peanut challenge (75 peanuts) and are on weekly maintenance. We have come a great distance considering he had massive wheezing attacks after someone opened a bag of peanuts 20 feet away from him, just from the dust. As always, we are open to discuss our journey and maybe hlp some other families who are in our shoes.

I must ask, has anyone considered that addressing the Microbiome of children and adults before trying this method might reveal an inability in the gut to process different foods. Consider that children do not play and eat in the dirt any longer, they are bathed with germ killing soaps and in my experience once they have a normal array of good bacteria in the gut and on the skin the health improves. Pin worms cannot even survive in children the gut is so clean. Probiotics that actually reach the gut and are not destroyed in the stomach is my first suggestion. Oh, whatever happened to the doctor who said “let me see your tongue?” A clean tongue may reveal the gut is working properly.

These articles about “safely introducing foods to babies” makes me laugh. Doctors are not at all concerned about “introducing vaccines”, which all contain toxic and neurotoxic ingredients that have been known to cause everything from cancer to death.

Ingestion takes into account a child’s natural defenses. Injection bypasses those natural defenses, including the blood-brain barrier, which is how aluminum and other neurotoxins find their way into the brain causing neurological damage.

Create the disease with vaccines, then create a vaccine for the disease created by vaccines. What a great business model!

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321467.php

https://www.ny.com/1964/09/19/peanut-oil-used-in-a-new-vaccine.html

The Peanut Allergy Vaccine

There’s now a vaccine for peanut allergies—the potentially life-threatening ailment actually caused by vaccines.

https://www.naturalblaze.com/2018/04/the-peanut-allergy-vaccine.html

Isn’t that called Homeopathy?

I know this works because I was born with an egg allergy. Rather than stop eating eggs which as a child I had rashes all over my face and body. I decided to eat 1 egg per month, let it cause me the rash but let it work through my body by drinking water. I did this for about 2 years. Today I can safely eat eggs or any food with eggs without having massive rashes or breakouts. If my itching get a bit annoying I take an antihistamine and then I’m fine. I’m allergic to blue cheese and Brie as well, but since I breakout in welts and get diarrhea it’s a bit harder to control. No, I’m not lactose intolerant since I drink milk and eat cheese all the time.

When I was around 35, I worked at HMSA and had a great dental plan. So much so, my dentist wanted to change almost all my crowns. He was the old style amalgam guy, so I got a lot of Mercury poisons. This caused me to get double vision and an allergic reaction to almost everything (leaky gut). My Allergist gave me a homeopathic type therapy, where I took drops with minute amounts of 80% of my allergens. I was cured of most of my allergies, only my seafood allergy existed, which I could deal with. Fast forward to today, My dog had crazy allergies to everything due to vaccinosis. I was desperate and tried an Immune corrector supplement called Transfer factor Plus. I took it too, since my immune system was almost non-existent due to the mercury poison. Guess What, my dog is back to normal and I can now eat seafood. Transfer Factor is a godsend.

It makes me wonder if food allergies are the product of parents not being exposed enough to certain foods that cause the allergies.

This protocol is nothing new. I grew up in the 60’s and as babies and children, we ate everything. My mom let us try little bits of every food. She believed a varied, healthy diet was the best thing for kids. Food allergies were very rare back then. When I had kids of my own, I let them sample all the foods we grown ups ate…only because I didn’t want them to be picky eaters.

Neither one of my children had any kind of food allergy then OR now.

My daughter fed her daughter the same way, she is now 10 and has no food allergies of any kind. I believe the hysteria over food allergies caused more problems than it solved. Instead of exposing children to a varied, healthy diet at an early age, parents’ paranoia just made it worse. I’m not saying to let kids glom down a tablespoon of peanut butter every day, but letting them try new foods in moderation makes sense.

I had a fairly bad allergy to cats from age 18-about 23/24. I would visit my sister, I liked cats, and would weez, get rash on my neck, eyes water, I wold have trouble breathing and driving home. I would still visit off/on, it did seem to get better over time with baby steps. Then when I was about 24/25 my roommates wanted to get a cat. I agreed, they kept the cat out of my room. I had some trouble, but by then I had improved over time. Gradually my alleargy improved more to the point where it was about 80-90% gone. Took many years. Ironically 1 year after my roommates and I went our separate ways, they called me and asked if I wanted the cat. I had her for 13 more years, loved that cat so much, and my allergies disappeared and my wife and I hvae had cats since (been 25 years). I firmly believe you can gradually get rid of almost any allergy with the right treatment and exposure.

Back in the 1940’s, my mother took me to an allergist for my hay fever and hives. We definitely knew I was allergic to chocolate, strawberries, and some seafood. After testing, he told her that it would be easier to tell her what I wasn’t allergic to. He recommended this exact treatment. I could eat anything, just in small quantities. Lo and behold, my allergies went away.

Allergy shots are not a reliable treatment at all!

I’ve had two courses of treatment. First for a couple of years. The second for about 5 years. Both with minimal reduction in symptoms and that benefit decreased rapidly after discontinuing. So even with insurance, I’ve been out of pocket thousands of dollars and lost time. You have to wait 1/2 hour after the injection to see if you have an adverse reaction. Yes, I’ve had those too.

Further, other than being able to tell you that the immune response and immunoglobulin is involved, the doctors do not have a good understanding of why or how it works–when it does work. Further, there is no treatment for food allergies/sensitivities. You just have to avoid them. The only thing they can “treat” is airborne allergens; dust, animal dander, pollen, mold, yeasts. Or you can move out of state to where your pollens don’t occur or are driven to by wind. Good luck, because you may have to move again later.

Testing involves making scratches on your back and applying a liquid containing potential allergens. “Therapy” follows by injecting you with increasing amounts and concentrations of the identified allergens over time. You wait around to see if there’s an adverse reaction. If so, you get fast acting antihistamine, and epinephrine if it’s life threatening. The shots usually sting, often requiring application of an ice pack on the injection sites to reduce burning sensation.

Yeah, you can “try it” if you’ve got the resources (time, insurance, money, and access to clinic).

Your best bet is avoidance of the irritating substance, followed by using antihistamines if exposed (or best proactively if you think you will be exposed), and then epinephrine injection(s) followed by ER admission if your reaction is severe/life threatening. It also helps if you are not exposed to extensive air pollution. Yeah, good luck with that one too.

Old school antihistamines (e.g., Benedryl/diphenhydramine HCl) act quickly (20 min) and last 4-6 hours; may cause drowsiness, especially with alcohol. Second generation antihistamines (e.g., Claratin, Zyrtec) take about an hour to start being effective and last up to 24 hours, and typically do not cause drowsiness.

My son is currently going through this program and will be eating his first peanut by the end of the month.

It is life changing. We lived in constant fear. People don’t understand. His teacher handed him a Twixt for Halloween. That could have put him in the hospital.

Hard to understand how this seemingly comprehensive article could not mention the LEAP study (New England Journal of Medicine), LEAP-on study, the work of Dr. Gideon Lack (Kings College, London) and the “Bamba” story – Lack’s observation of a real life situation in which children in two communities – very closely linked through genetics, culture and cuisine – had vastly differing incidence of peanut allergy.

From a very early age, virtually all children in the low-allergy community snacked on “Bamba” peanut flavored puffs. (peanut version of Cheetos, cheese puffs, etc)

Here’s a link to the NPR story…..

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/02/23/388450621/feeding-babies-foods-with-peanuts-appears-to-prevent-allergies

Since I AM pre-1980 in My Allergy & Asthma life of 45 years,,, I CAN SAY! When EVER the Medical Fields SAY they can ReIntroduce SMALLER Dosage Therapies,,,, THEY HAVE NEVER REALLY WORKED! It’s JUST that THE WORLD FORGOT the CONSEQUENCES of Experimenting AGAIN! PLUS….

It IS MY Experience that NEW ROUNDS of WHERE the FOOD Industry,,, TRIES to GET AWAY with ADDING Levels of such Allergens INTO Products!!! INCLUDING “EPI-PENS” and FLONASE and NOW also Loradine! In which up to 50% of the Solution (or Other Ingredient) IS LACTOSE!

I have NEVER come Across a NUT with/and/or ALSO Asthma,,, THAT ISN’T also at least Sensitive to MILK! And I DON’T mean just an Upset Tummy… I mean a REAL Anaphylaxsis Allergy!!! Which in MY LIFE has Always BEGGED the Question….

WHO are the “STUDIES” REALLY based on????

Fabulous article and wonderful, thoughtful comments (nice change from most Comment threads).

My son has a very severe but not life threatening peanut allergy that his mother discovered by accident as in the article. It’s enough for an EpiPen or its competitor (thank God) Auvi-Q.

I’ll definitely be investigating all the paths to possibly alleviating this that commenters and the article mentioned.

Thank you to all who took the time to comment.

Avoidance is one way forward, but “treatment” is the way chose to go. given that we HAD a laundry list, there are only so many things one can avoid before it comes back to haunt you.

“In the years that followed, for reasons not well understood, food allergies became more common among U.S. children.”

Actually, the reasons are well understood. Check out this podcast by Science Vs that goes through how a scientist figured out what happened

https://gimletmedia.com/shows/science-vs/2ohd7e/peanuts-public-enemy-no-1

“In 1987, when EpiPens came out, there’s an increase in food allergies.” So, are EpiPens to blame for allergies? I think the answer is yes because parents upon hearing the “allergy/allergies/allergic reaction” freaked out and bought those EpiPens. You know what? People who grew up prior to the 1990s, had 0, that’s “zero” food allergies! Why? We ate more NATURAL foods than processed foods back then. And also because most of these pregnant mothers were either picky eaters or didn’t eat any peanuts before their pregnancy causing an autoimmune rejection response to anything that was avoided prior to those 9-10 months, therefore causing the child to born with such a preventable allergic “disease.” I believe OIT would help if allergic food products are taken a little at a time and maybe also depend on how the allergy developed. I never had allergies until after I went to an annual summer vacation to Canada and came back to the US with food poisoning. Afterwards, I, all of a sudden, became allergic to shrimp. Now, living about 20 years with this shrimp allergy, I found out that if I drank large amounts of water after eating shrimp the allergic reaction never came up at all.

Bryan, my own experience does not line up with your theory that maternal dietary avoidance causes preventable allergic disease. My wife has always been a peanut lover, and continued to routinely eat peanut products while pregnant with all of our children. Yet, one of my daughters experienced moderate allergic reactions (dramatically swollen face and arms, no anaphylaxis) to peanut butter when she was a baby. No change in peanut consumption for mom, but one out of four of our kids developed an allergy. Thankfully, my daughter seems to have outgrown her allergy with time (perhaps aided by a form of environmental immunotherapy, given that her siblings have continued to eat peanut products and there are likely trace amounts of peanut on most surfaces in our home).

Nice anecdote… Of course, it’s all nonsensical babbling and one person’s experience – but don’t let that stop you from claiming it’s all THE ONLY TRUTH.

My grandmother was allergic to eggs. My other grandmother was allergic to aspirin. Both of them ate healthy unprocessed food. I had friends with food allergies growing up (in the 70’s and 80’s). What you are claiming is survivor bias. They didn’t survive childhood so you didn’t know them. There is no doubt processed foods are bad and antibiotics cause a host of problems. There is no correlation to EPI pens other than they have saved lives.

You state food allergies didn’t exist prior to growing up in the 1990’s. Incorrect. I had a severe reaction as a teenager in 1986 to a very natural food, cantaloupe. It was a food I had eaten regularly and in large quantities until one day it caused the entire inside of my mouth and some of my throat to swell. My food allergy cannot be from a lack of exposure if one day I could eat the food and the next I couldn’t.

An infection of parasitic worms (hookworms, whipworms) is known to have a regulatory effect on the immune system that can ameliorate many autoimmune disorders, including allergies.

Do a search on “hygiene hypothesis” and “helminthic therapy” for more information.

I had asthma very bad when I was a child. I am 65 now and at the time there wasn’t the treatments they have now so very often I was near death. I grew up in Southern California in an agricultural area and I was allergic to nearly everything. When I was 17 we moved to Colorado where the air was dryer and less pollen. It was in Colorado that my mother got the idea to start sprinkling tiny amounts of bee pollen from the area we lived in, on my food. She gradually increased the amount and it wasn’t long before I no longer had to take the shots and had no signs of food or any other kinds of allergies.

The internet has made the Snake Oil Salesman the Doctor of the 21st Century.

My son was born with a “light” allergy to peanuts, breaking out in hives following the eating of peanuts. We found that smooth peanut butter didn’t give him, unlike his reaction to chunky peanuts (which contain actual peanuts). Today he’s in his 20’s and appears to have no reactions to any peanuts. Not every child is the same, and not everyone has the same reaction.

AR101 is just fat free peanut flour, and nothing else. Something that can be bought at any grocery store for a few bucks, and yet pushed forward by Aimmune with the complicity of the FDA, and once approved it will be sold for thousands of dollars.

That is, yet another FDA validated scam!

Great article with lots of good information.

Unfortunately, I don’t like how the focus of almost every food allergy treatment is almost always OIT and the two FDA food allergy treatments that are in the pipeline.

Another treatment option that works for both environmental AND food allergies that can get people to bite-proof has been available for 50 years in the US and is a safer, less invasive version of OIT in the form of liquid-antigen multi-allergen SLIT. Over 250,000 people have been treated safely and effectively with SLIT at one clinic and now another one has opened on the East coast. This version has essentially no risk of serious reactions or anaphylaxis and people can safely do it at home without the need to be at the doctor’s office frequently.

Dr. Kim, who was mentioned in the study is a big proponent of the faster dosing version of SLIT and can most likely attest to its efficacy and usefulness.

Unfortunately, it’s not sensational like OIT because it takes time to change anything that doesn’t want to change and SLIT is a long term (1-3.5 yrs for buildup) option. Although there are plenty of studies that show it’s effectiveness if you know how to read and interpret the data.

Why are studies going after the more aggressive, riskier option when there’s a safer, more lifestyle-friendly option? Sadly, most families have little to no information about SLIT and most allergists don’t ever mention it as an option. Why? That’s a question to ask. When you do question the main research allergists, they give bad answers that are easily refutable if they talked to anyone using the treatment in private practice.

If you want to help people with environmental allergies, food allergies, FPIES, early introduction, low-income individuals, rural area families, etc…this form of SLIT could easily be an option that would help them all.

An MD referred me to this recently: There’s a new and natural method available in Switzerland. It has extremely high success rates and usually only takes 2 treatments that last about 10 minutes. The method is called EPI, short for “Extraction of Pathological Information”. Plus, there are medical doctors who already support this actively…

It is apparently especially effective for all allergies and food intolerances.

They have videos on http://www.hannesjacob.ch that show the studies they have made (you must enable the English subtitles since the videos are in French). So far, I found 1 Clinical study report in English: http://www.hannesjacob.ch/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/EPI-Extraction-of-Pathological-Information-Clinical-study-report-Christian-Bouillaguet-M.D.-2018.01.30.pdf

This definitely seems worth a try…