It seemed like a great idea. We were two American journalists visiting London and had a dinner party to attend. Why travel underground on the Tube when we could rent a couple of bicycles and see the city? But somehow it all went wrong.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, author M.R. O’Connor shares a story that didn’t make it into her latest book “Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World,” (St. Martin’s Press.)

We rode our bikes past Westminster Bridge, Big Ben, and Buckingham Palace, then headed south toward Pimlico, where we were expected for dinner. My friend Tom decided to take a scenic route, following the River Thames’ northern bank. At a critical intersection, his phone’s turn-by-turn GPS directions gave instructions that seemed counterintuitive, but we followed them, became totally lost, and arrived two hours late at our destination, rumpled and humiliated.

The irony of our tardiness was lost on no one. I was in London to attend a conference held by the Royal Institute of Navigation on the biology of animal navigation. What mechanisms allow sea turtles, whales, and migratory birds find their way across thousands of miles with unerring precision? Tom and I had perfectly illustrated the gaping divide between humans and the animal kingdom when it comes to orientation and navigation.

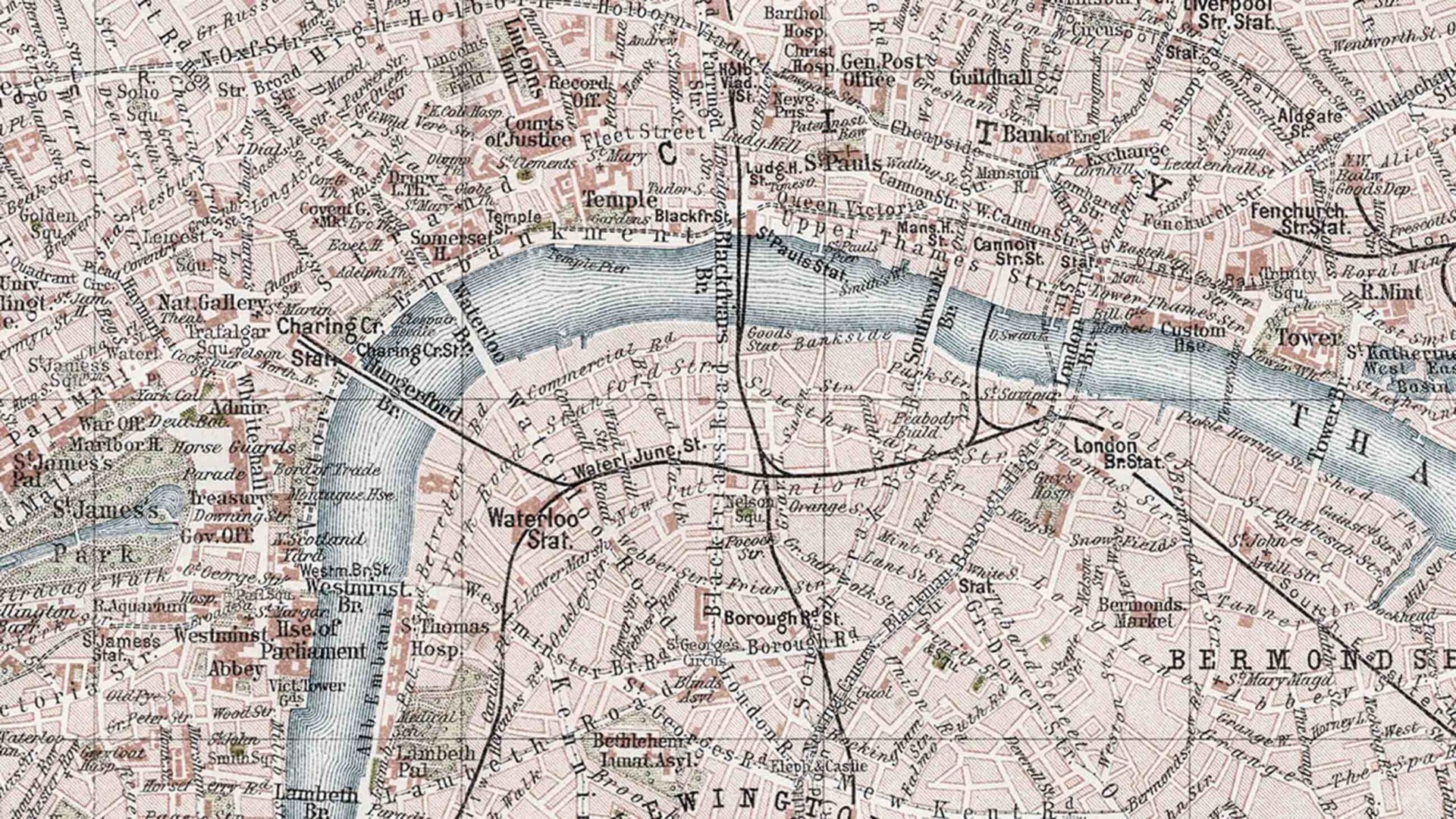

Humans are uniquely capable of becoming lost, so over time we’ve had to create a variety of strategies for finding our way. For one thing, our brains have evolved incredibly developed and large hippocampi, the neural locus of wayfinding and episodic memory, than would be predicted for other closely related species, which allows us to employ memory in the task of navigating. Additionally, we have long used diverse cultural practices for navigating, from environmental cues like the sun and stars to oral storytelling as mnemonic devices for recalling topographic information. In the Western world, the most dominant of these practices has historically been the map — once drawn by hand and now rendered by GPS devices.

So why is it that our maps — digital or otherwise — so often get us lost? For one thing, they’re usually used for exploring unfamiliar places. Many indigenous navigators, in contrast, practice their skills across large but generally known areas; even if the individual does not have direct experience of a place, they will likely have heard descriptions of it, some of which are passed down generationally. For Westerners, the combination of a lack of local knowledge and unquestioned faith in the power of a map can be disastrous, particularly when we forgo our own perception, instincts, and problem-solving skills. Far from home and familiar reference points, Tom and I followed our GPS’s directions, compounding one bad decision after another, even though we knew Pimlico was south.

People seem to have an astonishing ability to believe their GPS is always right, even when such belief defies logic. In 2016, for instance, an American tourist arrived in Iceland and put the address of his hotel, which he knew was 40 minutes away in Reykjavik, into his rental car’s GPS device. He then drove six hours to a small village in the north of the country, not knowing he had inadvertently added an extra “r” to the name of the road. Along the way, he passed signs indicating Reykjavik was in the opposite direction but his faith in his GPS eclipsed what he could see with his own eyes.

It could also be that our unshakeable trust in GPS has historical roots that go deeper than the technology itself (which has only been on the mass market for a couple of decades). In his book “Masons, Tricksters, and Cartographers,” David Turnbull, an Australian scholar, investigates how maps came to be so embedded in modern consciousness, to the degree that we fail to consider other ways of accumulating knowledge.

“We are largely unconscious of the centrality of maps in contemporary Western life precisely because they are so ubiquitous, so profoundly constitutive of our thinking and culture,” he writes. “We are bombarded by maps in our newspapers, on our televisions, in our books, and in our getting around the modern world. The cartographic trope is all pervasive.”

Turnbull locates the origins of this phenomenon in the cartographic revolution around 1600 in Europe. At that time, maps began to be seen as emblematic of scientific knowledge, and in exchange scientific theories were conceived as maplike. The culmination of this process, according to Turnbull, came in 18th-century France when “state, science, and cartography became so strongly intermeshed that in effect they coproduced one another.” The result of this historical process is the conviction that “maps are a mimetic reflection of external objective space.”

The truth is more complex. Maps are far from culturally universal, and they are far from objective. Different cultures have produced different ways of building knowledge, particularly about space. For instance, in the Kalahari Desert, the Hai||om San people are expert hunters and trackers, capable of finding their way across vast distances, yet do not use a map. Anthropologist Thomas Widlok has found that it is language — the Hai||om San’s use of spatial description in conversation — that constantly reinforces their orientation skills. They use geocentric coordinates to describe space, and also engage in what Widlok calls topographical gossip, constantly sharing information about places, travels and the landscape that allow them to fix their location.

Maps represent a point of view, and the map reader brings subjective ideas, knowledge, and experience to the act of interpreting them. And that’s when maps can often seem to betray us. Years ago, I set off in a car from the capital of Mozambique, driving south with the intention of crossing the border into South Africa. I felt completely confident about my route because I had a small map in my glove compartment. But as night fell, I discovered that the “road” on the map I was following had become a sandy track meandering through an elephant preserve. Soon this sand track was just one of hundreds crossing each other maze-like through grassland, and my car became stuck, unable to go forward or backward. I resigned myself to sleeping on the roof before I was rescued in the middle of the night by a passing LandCruiser.

Had I simply been paying attention to the landscape around me, rather than focused on the infallibility of my map, I would have likely noticed how poor the roads were gradually becoming, even though they looked like highways on the piece of paper. What might I have done differently? Perhaps to have remembered that, as Turnbull points out, maps “are not the only way of knowing the world or assembling knowledge.”

I might have stopped to ask a local for directions.

M.R. O’Connor, a 2016-17 Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT, writes about the politics and ethics of science, technology, and conservation. She is the author of, most recently, “Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I relied on old style maps when there was no GPS on celphones yet. When the GPS started to be in use, I still checked the map and used my GPS as I went along. If the GPS map is not updated, I can end up in a one-way street. Having consulted my map first, common sense acts up when the GPS seems to be bringing me to an uncertain way.

Now, I rely mostly on GPS since maps are not so common and they tend to be outdated. However, common sense is not be ignored.

For me & my parents the lack of knowing that their commercial timeshare was in North myrtle beach has slipped us up a couple times with onstar even the mcdonalds app was a ledging that their was one when in fact that was south of there

When we lived in Alaska we would always rely primarily on visual observation of the landscape and its land marks for our way finding, particularly hiking, biking or boating in an area new to us. This isn’t to say that we didn’t use/rely on GPS or topographical maps; we carried both with us most of the time, along with a Personal Locator Beacon (so someone else could find us in an emergency) and of course we also carried bear spray and a firearm, which was to give us a reasonable chance of finding our way passed an aggressive bear or mother moose One year while fishing in Prince William Sound we learned an important lesson in way finding. As we motored our skiff out of the cove in which our cabin was located and into the main passage about a quarter mile away, I took note of the landscape eyes forward, but coming back in the afternoon when attempting to navigate from the passage back to the cove no entrance looked familiar, which is when we realized that we failed to look with our eyes rearward when we left the cove and entered the passage earlier that morning. The human head and brain is set up to look forward as the body is set up to move foward.

It is not intuitively obvious or physically natural to turn around to see where you’ve come from in order to complete the mental map for the returning. Metaphysically this points to one of our major failings as human beings, which is the failure to see where we’ve been in order to best move ahead. That said, we did eventually find our way back to the cove and cabin after two or three wrong entrances. The experience shook our self-confidence in our self-reliant way-finding to the point that whenever we were in new marine territory we would always enter the camp/cabin location in our GPS before heading out.

Just yesterday I said to my wife as we were driving in search of a piece of undeveloped property, “I think it will be down around this next curve.” She promptly pulled out her phone and asked what’s-her-name to give us directions, and then couldn’t understand why I was upset about it. Don’t hand off responsibility for where I am and where I am going to an algorithm. I’m hyper-aware of what’s going on around me when I’m searching – sunlight angle, time of day and year, what roads we’ve passed, signs, rise and fall of the land. And if/when your phone fails, I’ll be able to find my way. My wife, on the other hand, would be still be staring at her phone, wondering what to do, now…

“People seem to have an astonishing ability to believe their GPS is always right, even when such belief defies logic.”

I have prosopagnosia, so I have an excuse: I once arrived in Dallas/Ft Worth, decided on a whim to drive to Denver (Colorado) and hired a car. Half way to Denver (West Texas, another Denver apparently) I drove into a class 4 tornado.

This article highlights the ever-growing importance of reconciling scientific knowledge with ecological knowledge (Common Sense!).

I can get lost with or without a GPS. It’s just a knack I have.

I am reading more and more of these articles about people being flat-out stupid. Put your phone down and use your brain. But you knew you were going the wrong way and still did it is the problem it has nothing to do with maps or GPS and has to do with people being lazy and stupid

Humans innately have the same ability as animals, it is just that most never have to use their senses to figure out how to navigate the spaces we occupy. We also tend to move around a lot, whereas animals inhabit a defined area- including migration paths- which they become familiar with out of necessity.

I learned at an early age to be aware of my surroundings and to orient my self to the landscape, no matter where I am. I wander deep into the forest, sans GPS, and always know where I am via standardized USGS maps and a compass, which I rarely need. It’s a matter how of learning how to be in tune with abilities we already have. Look around you, not down at your device. And then there will be the day when GPS units are all off because of solar activity- A very real scenario that has NOAA keeping a vigilant eye on space weather.

GPS is a useful tool when one has no idea, but I will always check mapquest and scope out the route before I rely on GPS. Once I start MY PREFERRED route, GPS can catch up. I don’t trust it to give me the most common sense route. It has put me onto a highway and off within one exit (try crossing several lanes of traffic in 1/4 mile on a busy highway) when a street would have provided a much easier route. My rule is to know before I go.

What a wonderful article. So if the author can answerme this : What happens to our intuition in an age such as ours? What do I have to read in order to find out?

Thank you

HI John, I would definitely start by reading my new book Wayfinding :) The short answer is: I don’t think we have a chance to cultivate intuition if we always reach for a device first. Best, Maura