GPS Is Vulnerable. New Technology May Be Required.

In September 2025, a Widerøe Airlines flight was trying to land in Vardø, Norway, which sits in the country’s far eastern arm, some 40 miles from the Russian coast. The cloud deck was low, and so was visibility. In such gray situations, pilots use GPS technology to help them land on a runway and not the side of a mountain.

But on this day, GPS systems weren’t working correctly, the airwaves jammed with signals that prevented airplanes from accessing navigation information. The Widerøe flight had taken off during one of Russia’s frequent wargames, in which the country’s military simulates conflict as a preparation exercise. This one involved an imaginary war with a country. It was nicknamed Zapad-2025 — translating to “West-2025” — and was happening just across the fjord from Vardø. According to European officials, GPS interference was frequent in the runup to the exercise. Russian forces, they suspected, were using GPS-signal-smashing technology, a tactic used in non-pretend conflict, too. (Russia has denied some allegations of GPS interference in the past.)

Without that guidance from space, and with the cloudy weather, the Widerøe plane had to abort its landing and continue down the coast away from Russia, to Båtsfjord, a fishing village.

The part of Norway in which this interruption occurred is called Finnmark. GPS disruption there is near-constant; problems linked to Russian interference have increased since the invasion of Ukraine.

It’s one of the starkest geographic examples of how vulnerable GPS technology is. But such disturbances happen at a lower level all over the globe. The world’s militaries (including that of the United States) are big culprits, breaking out devices that can confuse or disrupt drones, missiles, and aircraft. But the equipment required to interfere with GPS at a less-than-military level is cheap and accessible and affects other aspects of life: Truck drivers, for instance, use it to look like they’ve delivered cargo on time. Players use it to fool augmented-reality games.

“Sooner or later, we’re gonna see bad things happening here. So we need to armor up for it before it happens.”

Given all this disruption, more U.S. institutions, from the Department of Defense to the Department of Transportation to the Federal Aviation Administration, are making moves toward alternatives and complements for GPS, though perhaps imperfectly. And the existing system has been undergoing a huge modernization program, introducing better-encrypted signals for military users, more varieties of signals for civilians, and higher-power signals for both to the tune of at least $22 billion. The military’s 2025 budget additionally requested $1.5 billion for more resilient “position, navigation, and timing” programs. Other departments have invested smaller amounts. In October 2025, for instance, the Department of Transportation awarded $5 million total to five companies to develop and demonstrate technologies complementary to GPS.

The update’s goals are to make the system more accurate, and harder to mess with. But as threats increase in frequency and sophistication, more work is necessary. “Sooner or later, we’re gonna see bad things happening here,” said John Langer, a GPS expert at the Aerospace Corporation, a nonprofit research organization. “So we need to armor up for it before it happens.”

GPS is the invisible spine of society, in more ways than most people realize. It became central quickly after the satellite system, built in the 1970s for the military, was optimized for civilians. “Part of what makes GPS so successful is that it’s ubiquitous and it’s inexpensive,” said Langer.

Losing GPS would mean losing a lot more than Google Maps. The technology is integrated into everything from lights that turn on at sunset to dating apps that match users nearby. Its signals also undergird the electrical grid, cell networks, banking, defense technology, and the movements of robots used in industries like agriculture.

The U.S. government currently has 31 GPS satellites in orbit around Earth, and three other governments have their own systems: Russia made one called GLONASS, China created BeiDou, and the European Union built Galileo; all four systems’ data is available to the international community.

“Part of what makes GPS so successful is that it’s ubiquitous and it’s inexpensive.”

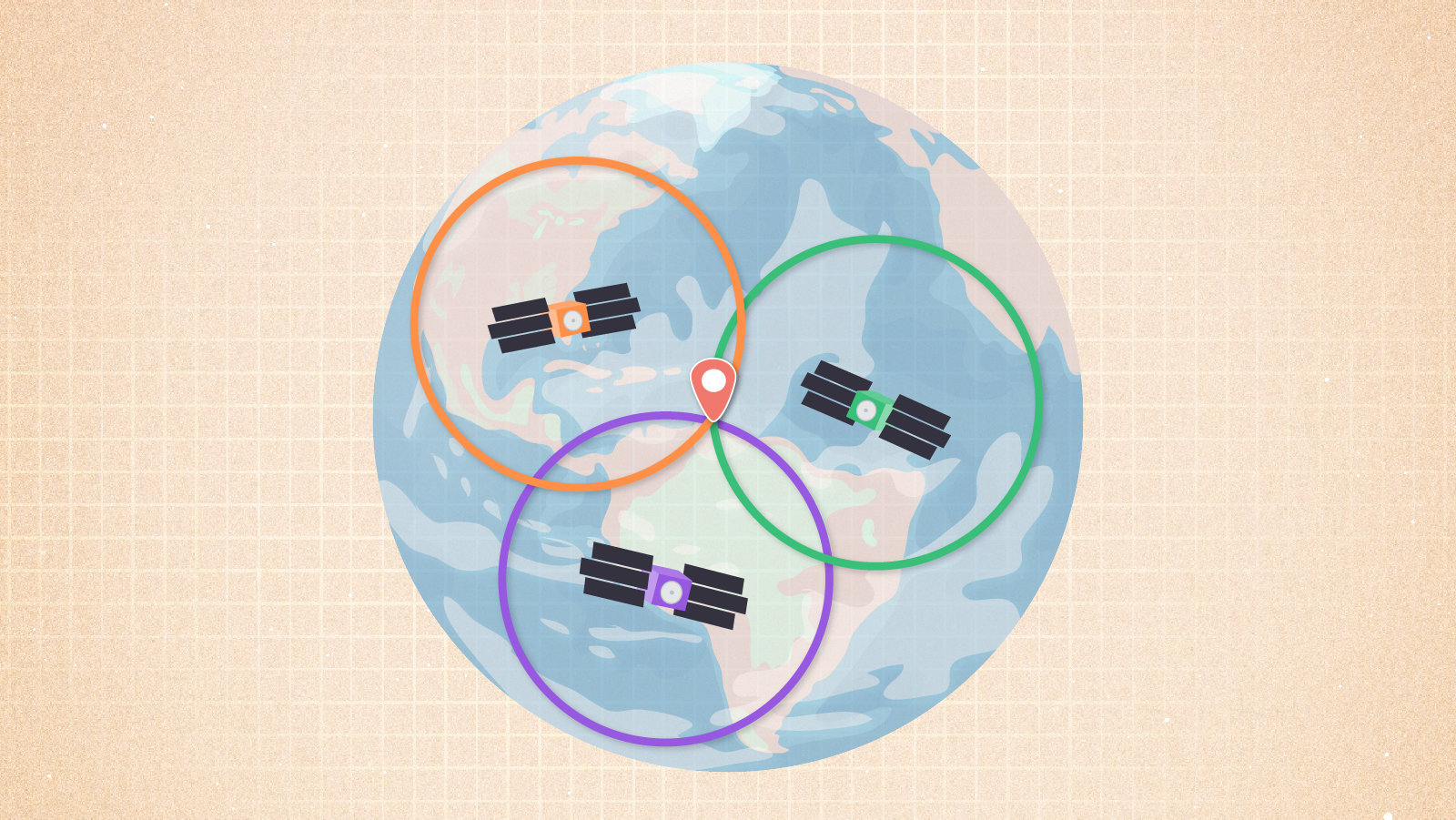

GPS works in a deceptively simple way: Each satellite carries an atomic clock aboard. It broadcasts that clock’s time toward Earth. That signal alone is what’s useful to energy infrastructure and financial transactions. But to get position information, a receiver — in a phone or other device — simply has to pick up signals from at least four satellites. It knows what time those signals were sent, where the satellites were when they sent them, and how long it took the signals to arrive. Through fancy triangulation, the phone (or guided missile) then computes its own location.

Or at least that’s the idea. GPS can be jammed, meaning that someone broadcasts a signal much stronger than that of GPS (which has had to travel across thousands of miles of space, and grows weaker with every meter), drowning the real signal in noise. It can also be spoofed, meaning someone sends out a fake signal that looks just like a GPS blip but indicates an incorrect location or time.

Threats like these were always a possibility — and those who built GPS knew about that problem from the beginning, said Todd Walter, director of the Stanford GPS Lab. “Around 2000 is when people got a little more serious about it,” he said. Hardware and software became cheaper, lowering the barrier to swamping or faking signals.

Problems ticked up when the augmented reality game Pokémon GO came online, in 2016. The game required people to travel to places in real life to win. Turns out, not all of them actually wanted to. “All of a sudden, everyone was interested in spoofing,” said Walter.

Pokémon GO cheaters used low-power devices close to the ground, and so didn’t affect cruising aircraft like Widerøe’s. The game made cheating high-tech and furthered methods and technology for signal scrambling, making it available to non-experts, Walter said. At the same time, spoofing arose in conflict zones, where drone and missile attacks are often guided by GPS. Don’t want to get hit by one? Fool its navigation system. “So now people say, ‘Well, we need to protect ourselves from that,’” said Walter. “And so then you see a huge increase in very powerful jamming and spoofing.”

In Norway, officials have noted that GPS disruptions, while most commonly affecting flights thousands of feet in the air, can also cause issues for police cars, ambulances, and ships. According to Espen Slette, director of the spectrum department at the Norwegian Communications Authority (known as Nkom), the agency has detected GPS jammers near hospitals, which could force life-saving helicopters to redirect to a more distant facility. Nkom has also clocked disruptions that affect agriculture and construction operations, while emergency responders have warned about how problems might home in on emergency beacon devices, like the satellite SOS buttons many people carry in the backcountry or aboard boats. The police’s chief of staff in Finnmark encouraged anyone venturing out to, old-school, carry a map and compass.

“It’s hard to grasp the full effect this has on society,” Slette wrote in an email.

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Such widespread disruptions are not isolated to the Russia-adjacent Arctic. There are hotspots in Myanmar, most likely associated with drone warfare in the area; on the Black Sea, publicly associated with Russia, which has denied some cases of GPS interference; and in southern Texas, potentially from drug cartels near the border. A report from OpsGroup, a membership organization for international aviation personnel, found a marked increase in spoofing in 2024. “By January 2024, an average of 300 flights a day were being spoofed,” the report said. “By August 2024, this had grown to around 1500 flights per day.” From July 15 to Aug. 15, 2024, 41,000 flights total experienced spoofing. (While in the U.S., it’s generally illegal for civilians to jam or spoof signals, military-led disruptions during conflict are considered a legitimate and legal use-case.)

The uptick indicates that there’s no going back to a world without disruption hotspots. And that, combined with humans’ dependence on GPS, is why scientists and engineers are working on ways to shore up the system — and develop backchannels so a single-point failure doesn’t come to bite anyone, in conflict or in peacetime.

“There are many ways to mitigate GPS disruptions,” Slette wrote in an email. He suggests setting up devices to use signals from all four international constellations, and to install better receivers and antennas. That’s easier for militaries or infrastructure companies, and hard for people who are just buying the latest model of cell phone and have no control over its innards. But existing backups can tell a given device that something fishy may be up. Planes have inertial navigation systems, which mostly use motion-sensing devices to get an independent measurement; phones do too, and they can also check their data against cell towers, to see if something is off in their GPS signal.

But the U.S. government is worried enough about GPS issues that, across civilian and military agencies, research and development for more robust and resilient systems is ramping up. In March, for instance, the Federal Communications Commission launched a proceeding on GPS alternatives, exploring tools that could be used in addition to or instead of traditional GPS.

The game Pokémon GO required people to travel to places in real life to win. Turns out, not all of them actually wanted to. “All of a sudden, everyone was interested in spoofing.”

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, and the Defense Innovation Unit, meanwhile, are investigating how quantum sensors might help with position, timing, and navigation. The United States’ military branches are also working on their alternative position, navigation, and timing capabilities, and their innovation arms like the Space Force’s SpaceWerx organization are running challenges to support alternative technologies. The Department of Defense acknowledges challenges to GPS and the consequent need to diversify the ways it gets position, navigation, and timing information, noting that it is pursuing the integration of alternative capabilities, according to a statement that public affairs officer Chelsea Dietlin requested be attributed to a Pentagon spokesperson. It is also looking toward working with commercial companies.

Even the Department of Transportation has a strategic plan that includes promoting technologies complementary to GPS. (Undark reached out multiple times to the Department of Transportation to request comment but did not receive a response.) A statement that FAA media relations specialist Cassandra Nolan requested be attributed to an agency spokesperson noted that the FAA is working on a system to detect GPS interference, and that it is working with the Department of Defense on navigation signals and antennas that are more resilient. In addition, the statement noted, the FAA already has “a layered aircraft tracking system that incorporates multiple technologies to guard against threats to Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS).”

But the newer efforts across government may not be as connected as they could be, according to Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, a nonprofit advocacy group that largely comprises companies working in the GPS-problem space. For one, he said, efforts to bolster military and civilian systems have a fairly strict line between them. And neither has been as effective as he’d advocate: On the military side, plentiful programs exist, but they may not be working together. “It’s not clear if there is any coordination or synergies between the projects or how much senior leader support there is for comprehensive solution sets,” Goward wrote in an email.

On the civil side, Congress mandated in 2018 that a backup to GPS be established, but only experimental systems exist so far. There also have been efforts to repeal the law, with the disputed rationale that funding a single system isn’t feasible and there are better paths toward resilience. Goward contended that the government has hoped the private sector will come up with a usable solution, saving the government from creating one itself.

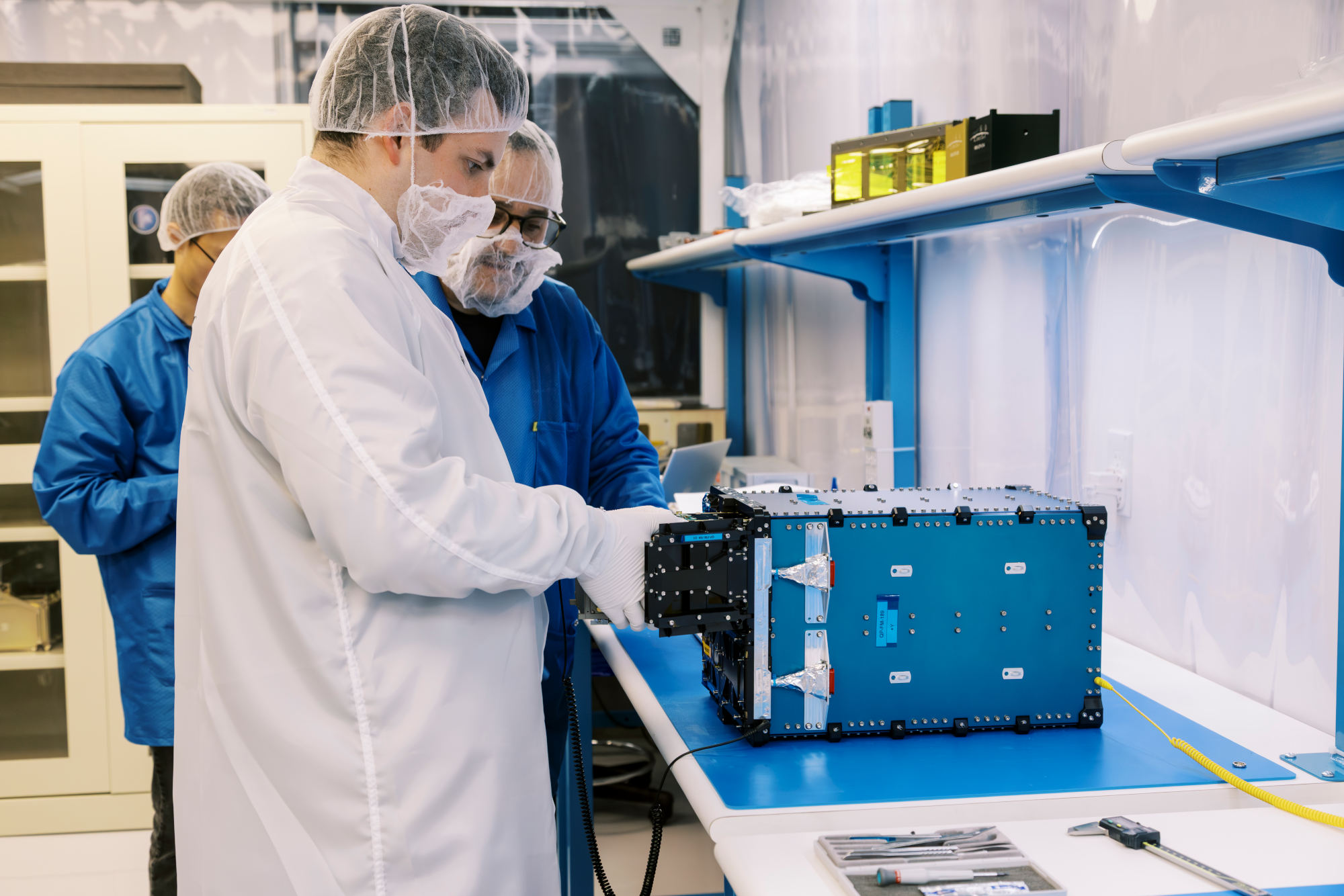

And companies are coming to cash in on that desire, offering their solutions to both government agencies and other industries. “Our founding hypothesis was ‘let’s take 50 years of lessons learned but throw out the rulebook and do a clean-sheet design of a new GPS system incorporating a couple of fundamentals,’” said Patrick Shannon, CEO of one such company, called TrustPoint. The company, which has hired scientific and engineering experts in signal processing and space, aims to have a fleet of small satellites orbiting much closer to Earth than the current GPS constellation, and transmitting at a higher frequency.

TrustPoint’s satellites, a few of which have already gone to orbit, also send out an encrypted signal — something harder to spoof. With traditional GPS, only the military gets encrypted signals.

Many Russian jamming systems, he said, work tens of kilometers from their ground zero (their ground zero usually being a truck with a generator aboard). But with TrustPoint’s higher-frequency signals, the effectiveness of the jammer goes down by three times, and the circle of influence becomes 10 times smaller, shrinking even more if the receivers use a special kind of antenna that the U.S. government recently approved.

Messing with signals becomes less feasible, given those changes. “They would need exorbitant numbers of systems, exorbitant numbers of people, and a ton of cash to pull that off,” said Shannon.

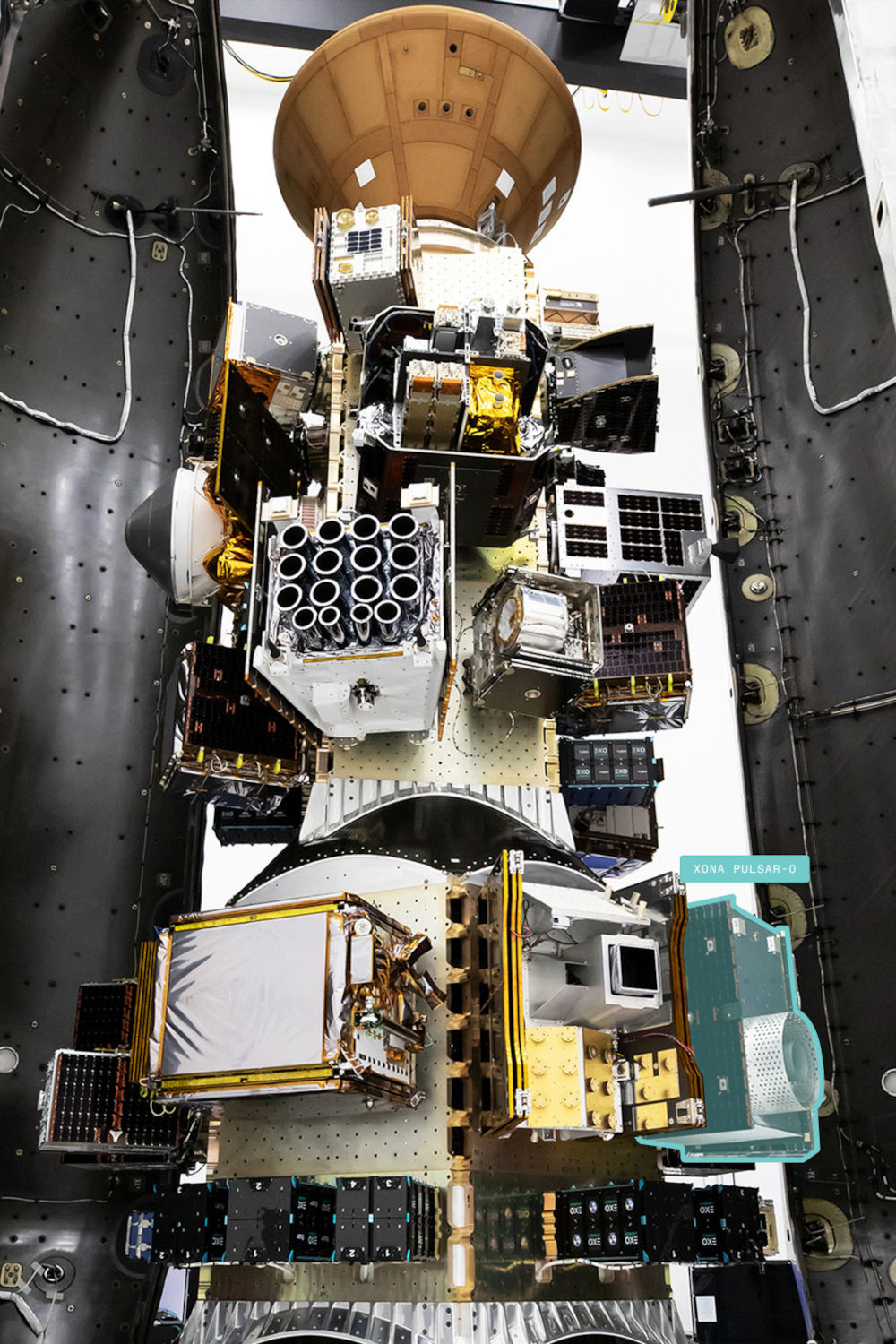

So far, TrustPoint has launched three spacecraft, and has gotten five federal contracts in 2024 and 2025, totaling around $8.3 million, with organizations like the Air Force, Space Force, and the Navy.

Another company, called Xona Space Systems, is also putting satellites in low-Earth orbit, and has worked with both the Canadian and U.S. governments. The company plans to broadcast signals 100 times stronger than GPS, giving users two-centimeter precision, and making jamming more difficult. The signal also includes a watermark — a kind of authentication that, at least for now, protects against spoofing. They have launched one satellite that’s being tested by people in industries like agriculture, construction, and mining.

TrustPoint’s technology may offer novel defense against the dark GPS arts, but Xona, whose founders met while students at the Stanford GPS Lab, may have an edge anyway: Its signals are compatible with current infrastructure, so no one has to buy a new device. They just have to update their software. “We are not building receivers ourselves,” said Max Eunice, head of marketing and communications. Instead, they’re relying on the billions of earthly devices that already themselves rely on GPS.

Other solutions, like one called SuperGPS, stay closer to the ground. They use radio transmitters on Earth to do the same things GPS satellites do in space. The setup, as demonstrated by scientists at the Delft University of Technology and VU University in the Netherlands, involves scattering radio transmitters around an area or using those already in place. Each transmitter is synchronized to an atomic clock, which sends the time to transmitters via fiber optic cable, which may already be in a place due to existing communications infrastructure. Receivers can collect signals scattered across a wide range of radio frequencies, making it more difficult to jam or spoof them. The team published a proof of concept in a 2022 Nature paper and is working on a second iteration called SuperGPS2.

Tom Powell, another GPS expert at the Aerospace Corporation, said that looking at alternatives and augmentations like these is important — even though GPS recently underwent the 25-year modernization effort, making its own signals more robust to vulnerabilities. “Now that we have delivered, or nearly completely delivered, this modernization, is there a better way to do it in face of the current realities?” he said. He and other GPS experts don’t have answers yet. “We’re just asking questions right now.”

“They would need exorbitant numbers of systems, exorbitant numbers of people, and a ton of cash to pull that off.”

Walter, the director of the Stanford GPS Lab, thinks that whatever a better path looks like, it will likely still include the old-school, original system. “There’s nothing that really does replace GPS,” he said. “I see articles saying ‘post-GPS World’ and so forth. But really, GPS, I think, will always be there.”

People will, and should, strengthen it, Walter added, but that bolstering is going to be piecemeal — efforts may work in a particular region, or they cover some of GPS’s roles (such as providing accurate time) but not others, or they may back up navigation but not be as accurate. They may also cost money. “GPS is free, so that makes it almost impossible to compete with,” he said.

GPS is also straightforward, said Powell. “As satellites go, they’re pretty simple,” he said. They point at Earth, and they transmit signals that tell what time it is. From that, humans get to live in an interconnected, chronologically propriocepted world. Figuring out how to keep it that way, though, is proving a little more complicated.

Your posts always remind me why I love being part of this community 🚀