Weed Regulation is Foundering. For Answers, Look to the Labs

On the Friday before Thanksgiving last year, the white dome of the Oklahoma State Capitol building stood etched against a bright blue sky. Summer Parker, her partner Charles Hrabina, and his 14-year-old daughter had driven to Oklahoma City from their home near Tulsa the day before and arrived early to prepare for a meeting. They crossed the ornate rotunda and entered an impressive conference room flanked by a wall of windows interspersed with dark wooden columns.

“We intentionally reserved this room,” Parker said as she walked in, pulling a wheeled trolley full of documents and other materials. “It’s important that we be taken seriously.”

The couple stood out against the usual stream of suits on government business. Parker wore a smart sweater dress, her gray-blonde hair twisted into dreadlocks. Hrabina, also sporting locs, had arrived in a forest-green three-piece suit with wide white pinstripes, punctuated by a burgundy hat, shirt, and shoes. Parker bustled about setting up, adding a handful of mints to each table — breath fresheners for the many marijuana smokers among the expected attendees.

Parker and Hrabina had arranged to meet with state regulators, marijuana users, and industry representatives on behalf of Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma, an organization they founded to improve the safety of medicinal marijuana. The couple said they were galvanized into activism when, after enduring a series of unexplained health issues, they arranged tests of some of the products they were using and discovered some were tainted with pesticides and toxic mold.

Summer Parker (right) and Charles Hrabina (left) in front of the Oklahoma State Capitol building in November 2024. Parker and Hrabina had arranged to meet with state regulators, marijuana users, and industry representatives on behalf of Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma, an organization they founded to improve the safety of medicinal marijuana.

Visual: Teresa Carr for Undark

Since then, Parker and Hrabina report testing approximately 200 marijuana products from dispensaries across the state, with nearly one in five failing for pesticides. In separate tests Jeffery Havard, who runs the Oklahoma City lab Havard Industries, LLC, tested 20 off-the-shelf marijuana joints and found that most were tainted with mold, and two with salmonella. He also found that labels overstated the amount of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the primary psychoactive component in marijuana, by an average of 72 percent.

Those issues are not unique to Oklahoma.

Ten years ago, medical marijuana was only legal in about half of U.S. states, and recreational use was outlawed in most of the country. Today, although marijuana remains illegal at the federal level, most states have legalized some use of the drug, setting off a green rush that, according to the data platform Statista, is predicted to bring in nearly $47 billion in revenue this year.

But in the absence of regulations or guidance from the federal government, states are struggling to oversee the flood of new businesses and products. Although experts told Undark that illicit marijuana remains the bigger safety hazard, across the country, independent tests have documented rampant problems with the legal products on dispensary shelves, including overstated THC levels as well as amounts of pesticides, mold, and heavy metals that exceed state limits.

Whistleblower reports and interviews with industry insiders show how some producers seek out lenient testing labs to examine their product. Some labs, in turn, may see a boost in business if they inflate THC values and greenlight contaminated products — a pattern corroborated by Undark’s own analysis of testing data obtained through state open records laws.

More potent products sell better, said Mike Graves, a one-time major Oklahoma grower who has tangled with Parker and Hrabina. In an interview with Undark, Graves acknowledged shopping around for favorable labs: “I’d roll a joint,” he said, and would “send it out to three different companies.” He would then use whichever company returned the highest THC level to provide the required testing certification for his products.

The industry’s problem, Graves said, is lax oversight of bad labs.

Now people across the country — including activists like Parker and Hrabina, as well as some producers and lab managers — are calling attention to the system’s failures. They’re pushing for reforms that, they say, will reduce the incentives and opportunities to cheat. And after years of playing catch-up, regulators in states such as Oregon and Oklahoma are finally developing the scientific infrastructure necessary to keep better tabs on product quality.

“I’d roll a joint,” Mike Graves said, and would “send it out to three different companies.” He would then use whichever company returned the highest THC level.

For Parker, marijuana is medicine. She has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a group of often painful, inherited disorders that affect the body’s connective tissues. She said marijuana helped her overcome an addiction to opioids, while also assuaging her chronic pain. “If it wasn’t for medical cannabis,” she said, “I would not be alive.”

People deserve to know what’s in their medicine, said Parker, but absent stricter oversight they must operate on blind faith. “We’ve been forced to believe that everything is as it should be — by the regulatory agency, by the brands, by the labs, by everybody,” she said.

“In fact,” Parker added, “they’re failing us.”

The corrugated metal building of Hometown Cultivation in Springfield, Oregon, stands in stark contrast to the lush hills of the surrounding Willamette Valley. But inside, the 22,000-square-foot windowless space is teeming with verdant growth.

Hometown is an indoor organic farm that grows approximately 24 strains of cannabis. (Technically, “cannabis” is the general term for the dried leaves, flowers, stems, and seeds, while “marijuana” refers specifically to products or plant parts containing more than 0.3 percent THC. But, in practice, the two terms are often used interchangeably.) Kerry Bennett, the farm owner, is tall and fit, a former Marine with black tattoos peeking out from one cuff of his company sweatshirt. Most days, he’s joined by Samwise, a stout black lab with a graying muzzle, who keeps lazy watch over the farm from the office couch.

Entering the grow area requires passing through a shower of pressured air designed to blast off any hitchhiking insects, spores, or pathogens. While contamination can happen anywhere along the journey from seed to shelf, one of the most obvious places is where the plants are grown.

During a visit to the farm in April, Bennett led the way through a series of rooms in the cavernous warehouse, tracing the lifecycle of cannabis from the bushy mother plants that yield cuttings (only female plants produce the THC-rich buds) to the final stage, when the leaves have yellowed and the plump buds are encased in crystalline trichomes that determine the strain’s flavor, potency, and effects. The entire cycle takes about five months.

“They call it a ‘weed’ because it grows like a weed,” said Bennett. The fast-growing cannabis plant is what’s known as a hyperaccumulator: It greedily sucks pesticides, heavy metals, and other toxins from the environment. The plant is sometimes used to clean up environmental waste; scientists planted industrial hemp, a type of cannabis, to remove radioactive material from farmland in the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Other contaminants can sneak their way onto the plant. Yeast and mold flourish when marijuana is grown, processed, or stored in humid environments without sufficient air circulation. Toxic chemicals can also get introduced during processing or packaging.

In Oregon, as in many other states, an overcrowded market means that cannabis growers operate on razor-thin margins, so they may do whatever it takes to get crops to market, said Bennett. That might entail spraying with pesticides — including some that aren’t regulated by the state — to control aphids, mites, or fungal diseases, or using kelp, a type of seaweed that is an effective fertilizer but that may contain heavy metals absorbed from the ocean.

“By the time we actually harvest, on any particular harvest, we have four-and-a-half to five months’ worth of expenses that have already been paid,” said Bennett, who schedules plantings so that a crop ripens every couple of weeks. What happens when there’s a risk a crop could fail? “It puts pressure on me to consider cheating, because I’m not so profitable that I can afford to lose even one.”

Market forces also compel growers to produce cannabis with higher levels of THC, as, on average, each additional percentage point translates to a higher sales price, according to a recent technical report by the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission. A pound of marijuana flower (the dry, smokable buds) that’s 25 percent THC sells for an average of $2,060 — $500 more than a 20-percent product. That price difference provides an incentive to fudge the numbers: The OLCC’s tests found that nearly three-quarters of marijuana flower purchased from retailers contained less THC than on the label.

Since Bennett established Hometown in the spring of 2024, he says several competitors have gone out of business or switched to selling to the illicit market. With extensive experience managing farms and other businesses, he runs a lean operation. Still, it can be a struggle for growers to make an honest go of it. “I’m in a 15-year-old used Toyota truck. I shop at thrift stores,” said Bennett. “I would be making a lot more money as an employee elsewhere than owning this.”

A pound of marijuana flower (the dry, smokable buds) that’s 25 percent THC sells for an average of $2,060 — $500 more than a 20-percent product. That price difference provides an incentive to fudge the numbers.

The upshot is that producers often harvest contaminated crops — and face substantial pressure to get them to market anyway, with as high a THC level as they can get.

From Bennett’s perspective, many of those quality issues stem from inexperienced players drawn by the promise of easy money. “Legalization began going across the U.S. and entities were investing, and there was this ‘build it and they will come’ mindset,” he said. But many people didn’t understand what they were getting into. “There’s a huge knowledge and skill and experience gap in cultivation,” he said. “There’s a lot of ignorance — and I don’t say that in a bad way — with state regulators on ‘Hey, how do we actually manage this?’”

Over the last decade, as more states have legalized marijuana, the responsibility of ensuring clean, safe products fell to regulatory agencies that had little to no experience with cannabis and lacked guidance from the federal government.

Most did not have the equipment and staff to test cannabis products themselves, and they were unwilling or unable create that technical infrastructure. “Early on, state-run laboratories were hesitant to get involved because of the federal illegality of cannabis and a concern about other federal funding they had,” said Gillian Schauer, executive director of the Cannabis Regulators Association, or CANNRA, a nonpartisan association of government agencies that regulate cannabis.

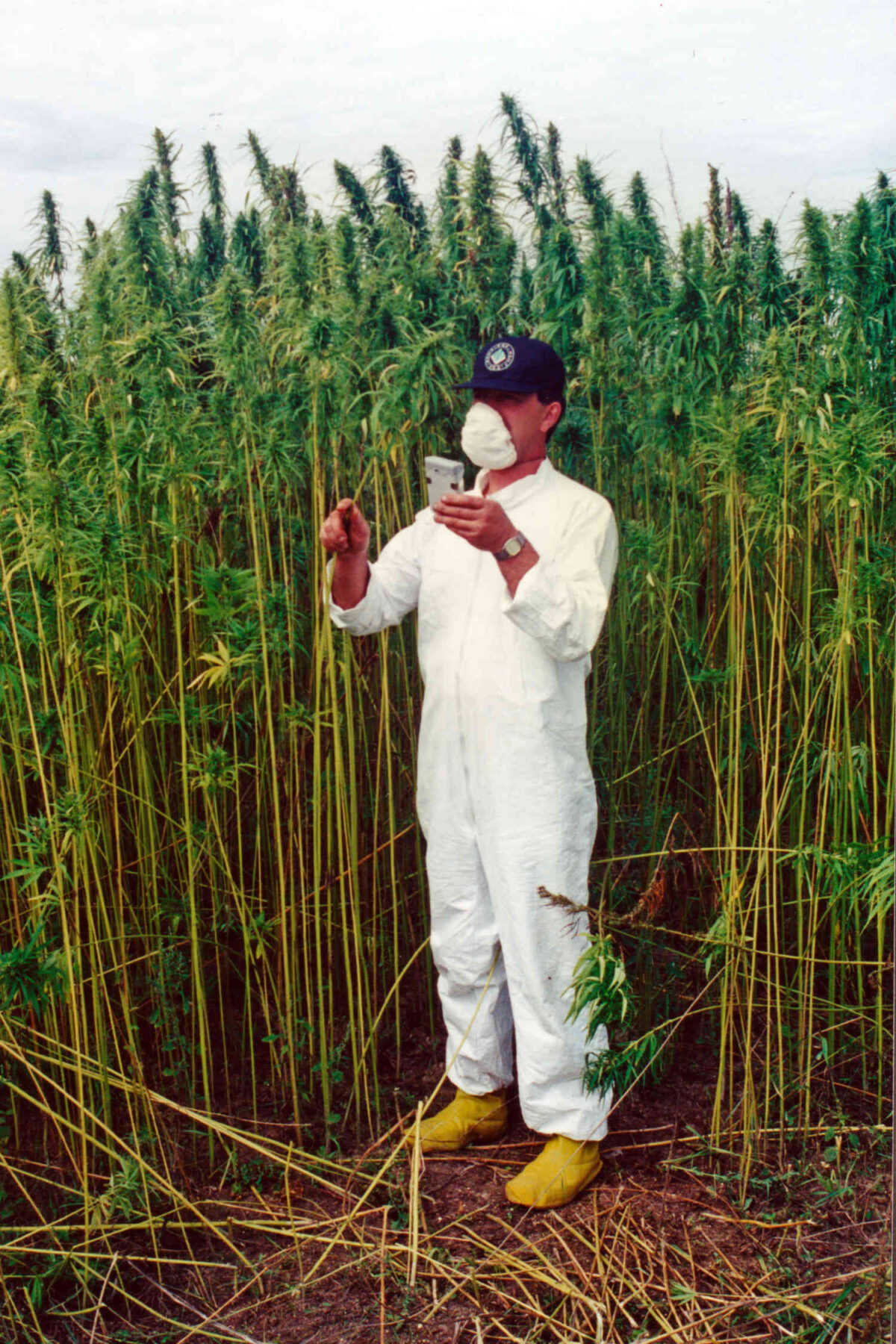

A Ukrainian scientist measures radiation levels in a hemp field near Chernobyl in the late 1990s. The plant was found to remove radioactive material from farmland contaminated by the 1986 nuclear accident.

Visual: Vyacheslav Dushenkov

Instead, they turned to private laboratories to do the work of examining and certifying products before they reached the market.

While specific standards vary, the overwhelming majority of states now require independent labs, licensed by the state, to test batches of marijuana or final products for purity and potency. For each batch tested, the lab issues a certificate of analysis (CoA) with contaminant testing results and details about the product’s chemical composition. Products that fail may be remediated — moldy cannabis might be treated with ultraviolet light to kill the microbes, for example — or destroyed.

The fatal flaw in this system is that cannabis labs are paid by the producers, which creates a financial incentive for labs to falsify results, said Josh Swider, an analytical chemist who runs Infinite Chemical Analysis Labs, which tests cannabis in California and Michigan. “For third-party testing labs, passing or failing a sample should never be in our interest,” he said. “As in, if it fails, it fails.” But cannabis testing labs face pressure to keep their clients happy with clean CoAs and high THC numbers, said Swider.

When Swider opened his first lab in San Diego about a decade ago, lab fraud wasn’t much of a problem, he said. Now, he knows of few honest labs that are still in business. Once a lab does a favor for a producer, they can’t really say no to doing another and things just snowball, said Swider. “More or less, you just look the other way, and you put things on the shelf; no one loses money.”

“The only people really suffering, he added, “are the consumers.”

Through open records requests, Undark obtained cannabis testing data from several states. An analysis of that data provides additional evidence that producers are shopping for labs willing to inflate THC levels and pass contaminated products.

The picture is especially stark in Oregon, where Undark received data spanning January 2018 to January 2023. Although the data shows that THC levels have generally risen over time, one Oregon testing lab, denoted in state records as Lab 129701, stands out for reporting significantly higher THC levels than other state-licensed labs.

In 2019, the lab was responsible for testing less than 2 percent of the state’s total samples. But in early 2020, producers began shifting more business to that lab. For most of 2022, it was running more tests than any other lab in the state.

Harvesters seemed to benefit: More than four in five licensed growers that switched to lab 129701 saw an increase in their average THC results.

By linking unique information from CoAs to product listings in the state data, Undark was able to identify lab 129701 as a now-closed location of PREE Laboratories, a testing company based in Corvallis. That lab and a second PREE facility are among four businesses currently facing the loss of their state license. According to reporting in the Portland Business Journal, lab employees were caught doctoring samples with a cannabinoid concentrate known as kief, which raises the potency of cannabis. Bradley Johnson, who was promoted to manager of the remaining PREE lab in May, conceded that someone spiked samples. “We’ve rectified the situation,” he said, “and have since moved on.”

He’d like to see the state take over THC testing. “Potency is definitely the driving force of the cannabis world,” said Johnson. Everything would run smoother if independent labs were only responsible for contaminant testing, he said. “We wouldn’t have clients hounding us constantly.”

Undark’s analysis of data from Massachusetts suggests that producers there shop for labs that are lenient with contaminant testing. In testing data reported to the state between April 2021 and December 2024, some labs failed products for yeast and mold contamination at a far lower rate than others.

Undark’s analysis shows that labs that failed few products gained market share at the expense of those with lower — and likely more realistic — passing rates. In the spring of 2023, for example, the lab Massachusetts identified as “Lab S” was testing 1 percent of all samples in the state data and reporting far lower contaminant rates than most of its competitors; by the fall of 2024, Lab S was testing more than one-third of samples in the state.

Undark identified Lab S as Assured Testing Laboratories, LLC, which in early July had its license suspended by the Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission for “failing to accurately report Total Yeast and Mold test results.” Assured founder and CEO Dimitrios Pelekoudas denied the charges, and the company has filed for an injunction to lift the suspension in court

“We run a very tight ship,” said Pelekoudas, who says his lab complied with all regulations. One reason his lab may show lower failure rates than others, he said, is that they’ve advised their grower clients on how to reduce yeast and mold. “Realistically, as people fail over time, they typically either will sink or swim and improve their practices,” he told Undark.

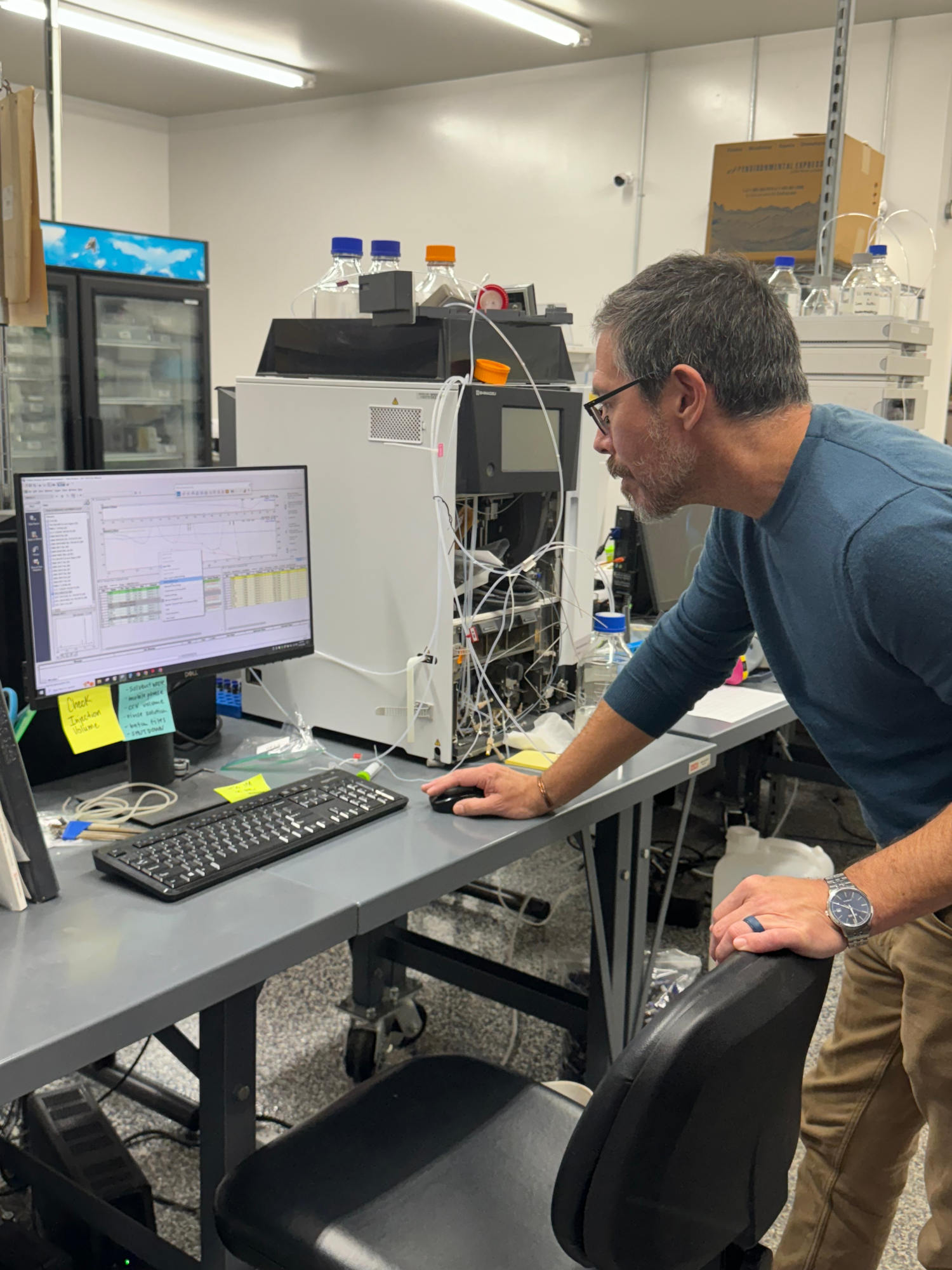

Sarah Cameron, who runs Scissortail Laboratories in Oklahoma City with her husband, Ian Cameron, spoke about industry problems at the Patients for Safe Access meeting in Oklahoma last fall.

The fatal flaw in this system is that cannabis labs are paid by the producers, which creates a financial incentive for labs to falsify results.

After decades of helping run labs for others, the couple cashed out their retirement accounts to start their own business when the state legalized medical marijuana in 2018. But the realities of working in a crowded, cutthroat market soon set in. “We found out pretty quickly that most of the industry doesn’t particularly care if they’re producing quality products or safe products,” Sarah Cameron told the group. “They just want to get that product out the door to make a sale.”

Frustrated by the lack of quality control, the couple agreed to test products for Parker and Hrabina, the activists who organized the meeting at the Oklahoma State Capitol, at no cost. Cameron said that she thinks of the testing as a public service: “I’m just thankful that we’re able to at least warn people that this particular product may not be safe for you to consume.”

Cameron is not alone in raising an alarm. She and other lab owners across the country are calling attention to the corruption in their industry. More oversight, they say, will make it possible for honest companies to stay in business.

At Scissortail later that afternoon, Cameron pointed out that labs aren’t always the bad guys. In Oklahoma, where producers submit their own products for testing, unscrupulous companies can tamper with samples to get a desired CoA, then use that certificate to sell lower-THC or dirty products. One way to discourage that form of cheating, Cameron said, is to require batches of product be locked away during testing. “Otherwise, there’s no way to prove that the product you’re getting is the product that is tested.”

Some testing issues stem from plain ineptness, said Ian Cameron. He recalled testing a cannabis-infused drink from a producer who, based on THC results from another lab, was having to add more THC than expected to reach the desired potency. But the other lab seemingly wasn’t proficient at measuring THC in liquids, Cameron said. Scissortail’s tests revealed that the drink contained a massive 700-milligram dose of THC, rather than the 100 milligrams it was marketed as.

But in other cases, Sarah Cameron said, she believes labs are clearly falsifying results for producers. In Oklahoma, as in many states, changing, inconsistently enforced regulations as well as tight profit margins have created an environment where people will cheat to survive. “We’ve had threats against us because we’ve failed someone for pesticides,” she said. “They’re like ‘I need this to pass so I can make payroll. It has to pass.’”

Havard, another Oklahoma City lab owner, said he has faced pressure to put his thumb on the scale when measuring THC. “We’ve had people ask us before if they could pay for higher numbers because they could do that at other places,” he said. Or people have gone to other labs where they know they can get higher potency numbers. “And that’s ended up costing us a lot of business.”

“We’ve had people ask us before if they could pay for higher numbers because they could do that at other places.”

People running labs in other states have similar stories.

The arrangement puts labs in a no-win situation, said Patrick Trujillo, director of the cannabis testing lab ChemHistory in Milwaukie, Oregon. “It’s unfortunate because the governments require these tests to occur, and they pretty much force us into a position as the police, essentially,” he said. But following the rules often means losing a client, he said. “They’re just going to go to another lab who will do exactly what they want, even if they charge double the price.”

The industry is so rife with corruption that all the players feel intense pressure to go along or at least keep quiet, said cannabis grower Trent Hancock, who says he had to shut down his farm in Oregon for refusing to cheat. Hancock has faced death threats, he said, as well as economic retaliation for speaking up about contaminants and THC inflation. “The market’s so hard,” he said, “that, say if you’re a farm, and you talk about this, your scores are going to drop, because the lab has that much power.”

It’s unclear what effect contaminated products are having on consumers’ health. But experts say there’s reason for concern. Decades of food safety research has shown that pesticides, heavy metals, and microbes can have serious health effects.

Still, in the absence of much research on cannabis contaminants, there’s still little direct evidence on the risks posed to cannabis users. At this point, scientists don’t even know the level of the contaminants users are exposed to, said Maxwell Leung, a toxicologist at Arizona State University who researches cannabis and health. “It’s a really challenging scientific question to quantify the amount of cannabis people use,” he said, and then estimate “the concentration of the contaminant” they encounter.

State regulations for cannabis, which vary widely, are for the most part based on those for other agricultural products. But unlike an apple, which can be rinsed of surface contaminants, marijuana typically isn’t washed before consumption, and it’s often smoked like a cigarette or heated into an inhalable vapor.

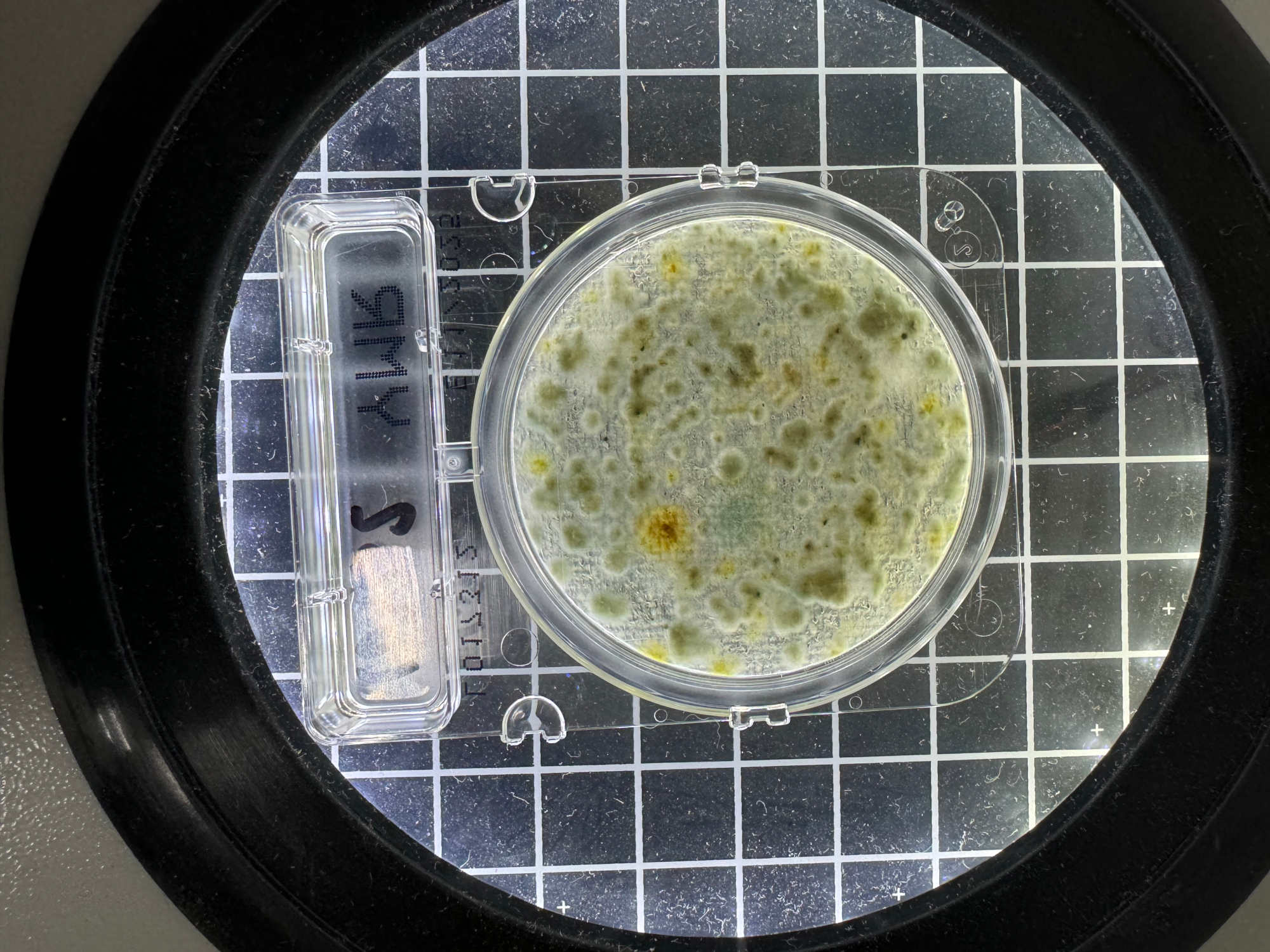

The flowers, or buds, of a cannabis strain called crema d’uva, shown after harvesting at Hometown Cultivation. The plant is covered in trichomes – tiny, translucent, hair-like structures that contain cannabinoids and other compounds which determine the strain’s flavor, potency, and effects.

Visual: Kerry Bennett

Unfortunately, there’s a paucity of research on the toxicity of inhaled contaminants, said Mahmoud ElSohly, a pharmaceutics professor who directs the Marijuana Project at the University of Mississippi. ElSohly and other experts, though, say there’s reason to be concerned. The body generally absorbs chemicals more readily from the lungs than the gastrointestinal tract, said ElSohly. “The flower, the plant material, is intended for inhalation and therefore is supposed to be pretty much sterile,” he said, noting that the university irradiates marijuana intended for research to make sure that it’s contaminant-free.

The little research available suggests that contaminants such as mold are most worrisome for people with compromised immune systems, according to Leung. “If those microbes get into the system and cause a secondary opportunistic infection, that can be very dangerous,” he said.

Leung is also concerned about the potential for pesticides and heavy metals to damage the nervous system, especially in people who use cannabis to ease symptoms for neurological conditions. For example, surveys have found that 25 percent to 37 percent of Parkinson’s patients use cannabis to reduce symptoms such as tremor, stiffness, and pain. But research suggests that organophosphate pesticides, which are common contaminants in cannabis, may be linked to the onset or faster progression of Parkinson’s disease.

Some cannabis users assert that tainted products have harmed their health.

Summer Parker, the Oklahoma patient activist, said that she was hospitalized four times in the fall of 2022 and spring of 2023 for episodes of fainting and stroke-like symptoms. Her partner, Charles Hrabina, also wound up in the hospital after his occasional migraines suddenly became unrelenting and he lost feeling in one side of his face. Frustratingly, they said, it felt like their doctors couldn’t pinpoint the cause of their symptoms.

At the time, the couple worked in marijuana sales, both promoting and using products from Graves Farms in Ardmore, Oklahoma, a large marijuana grow operation. On a tip from a colleague, they had products they were using tested at an independent lab, and were horrified to discover the tests showed they contained several pesticides associated with neurotoxicity — one pre-roll contained 65 times the allowable amount of the insecticide permethrin — as well as Aspergillus niger, a type of mold.

Parker and Hrabina blame the contaminated marijuana for making them sick, and medical records show that a doctor treating Hrabina identified exposure to pesticides and other chemicals as a possible culprit. After switching to another brand, Parker said her symptoms improved; Hrabina regained the majority of feeling in his face and his migraines lessened. Hrabina is angry that he could have inadvertently hurt others. “I poisoned myself. I poisoned my girlfriend. I probably poisoned 10,000 other people,” he said. “I was a good salesman.”

“We’ve had threats against us because we’ve failed someone for pesticides,” Sarah Cameron said. “They’re like ‘I need this to pass so I can make payroll. It has to pass.’”

Graves Farms’ owner Mike Graves, for his part, told Undark he does not use pesticides on his cannabis crop. The real problem, he said, is inaccurate lab testing. According to detailed documents Graves provided to Undark, he sent identical samples of products to six testing labs and got back wildly different results. One joint, for example, failed for pesticides at one lab, failed for microbes at another, and passed at three other labs. And potency was all over the map, with results for a concentrated oil ranging from 55.6 to 73.4 percent THC.

(Graves cut off dealings with Parker and Hrabina in May 2023, and they are currently involved in a legal dispute over money Graves says he is owed for products, and that the couple claim they are entitled to as compensation for unpaid commissions. The case is scheduled to be heard in district court later this summer.)

In the last two years, the Oklahoma Medical Marijuana Authority, or OMMA, has issued two separate recalls involving numerous Graves products, and in August 2024 the regulator suspended his processor’s license for “failing to meet state testing requirements and other violations endangering public health and safety” — an action that Graves has appealed.

For now, Graves said, the protracted legal fight with OMMA has put him out of business.

The lack of federal regulations or guidance, and the federal illegality of cannabis, puts states in a tough situation, because they each must create their own testing infrastructure, said CANNRA’s Gillian Schauer. “Usually, we would have federal agencies that would be involved in helping to set standards and develop methods and identify ingredients that needed to be tested for,” she said. “And the federal agencies are not doing any of that.”

The problem common to most states is that regulators — and the legislatures that fund them — haven’t put enough resources into overseeing their licensed testing labs, said Swider of Infinite Chemical Analysis Labs. “In my opinion, lab enforcement is the most important thing,” he said, noting that regulatory agencies should be doing more off-the-shelf testing and unannounced audits of licensed labs. “Because if you fix the lab problem, you kind of fix the rest of it.”

The solution is a state reference lab, said Schauer. Those facilities don’t have the capacity to check all cannabis products for potency or contaminants that could harm consumers. But they can help oversee the industry through inspections or spot-checks of products.

More states are opening such facilities, but coverage remains patchy: Of the 42 states that regulate marijuana, as of April 2025, only 16 have some form of state testing lab, or plan to open one in the next year, according to data from CANNRA. A few states have had state cannabis reference labs for five or more years, Schauer said. “But for the most part,” she said, “this is a very new trend that is an attempt to be responsive to the changing landscape on the ground.”

Even states with a long history of cannabis use have sometimes struggled to get testing infrastructure in place.

In 1973, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana. Voters there went on to approve cannabis for medical use in 1998, and for recreational adult use in 2014. Until adult use was legalized, what is now the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission was focused on alcohol, said Amanda Borup, director of policy, health, and education at the OLCC. “We had a whole new industry, basically, to regulate, but it looks very different, because with alcohol, it’s been around and been legal since prohibition,” said Borup. “And the federal government’s involved in that.”

By 2013, the state legislature had legalized medical marijuana dispensaries and had established some minimal testing requirements, said Borup, and people were starting to open businesses in lab testing. Soon after, when the state legalized recreational marijuana, it began licensing labs.

It’s at that point that the state made a crucial mistake, said Trent Hancock, the former Oregon grower. Like virtually all the states that followed, Oregon opted to license independent labs that would be paid by producers rather than the state. Some of the lobbyists who helped write the new regulations represented both producers and testing labs, said Hancock. “So, the labs got what they wanted, which is very high-volume testing,” he said. “And then the cannabis companies got what they wanted, because they’re the client of the lab.”

The green rush was on, and the resulting surplus of cannabis businesses has not only driven down prices, said Oregon cannabis industry attorney Vince Sliwoski, but also has overwhelmed the OLCC. Still, said Sliwoski, things are improving; among other changes, the state legislature has limited the number of new licenses for cannabis businesses and the OLCC has corrected “leadership deficiencies,” he said: “I feel like they’re a little bit more on track than they ever have been.”

“Usually, we would have federal agencies that would be involved in helping to set standards and develop methods and identify ingredients that needed to be tested for. And the federal agencies are not doing any of that.”

Last September, the agency sent notices to eight of the states’ 11 licensed testing labs, with four (including two locations of PREE Laboratories) facing shutdown for allegedly spiking samples with kief, the high-THC concentrate, and the remaining labs facing fines or license suspension for less serious allegations. While the more minor cases have been resolved, the others are still pending in court.

Around the same time, Oregon finally got its long-anticipated state lab up and running in Wilsonville, an industrial city south of Portland. The large lab, which is part of the state agricultural department, is light and airy, with three long rows of lab benches and several side rooms filled with gleaming new equipment. During a visit in April, a chemist was doing exploratory testing to see what pesticides producers may be using outside the 59 that the state currently screens for.

The new lab has two missions, said David Standiford, the laboratory compliance coordinator for the OLCC. One is to help the OLCC keep closer tabs on the market by supporting secret shopper tests, lab audits, and pesticide evaluation. All of that, in theory, will make it harder for labs to fudge their numbers. The other goal is to act as a resource for commercial labs to troubleshoot problems or improve their accuracy.

Milwaukie, Oregon lab ChemHistory was one of the four labs called out for smaller infractions. In an email, the director Patrick Trujillo characterized the errors as minor and noted that the company had paid a hefty fine and implemented safeguards to keep it from happening again.

For Trujillo, who has been pushing the OLCC for stronger oversight since 2016, the crackdown is long overdue, he told Undark: “I welcome it.”

For others, the state’s actions may be too little, too late. In early July, the cannabis testing company Green Leaf Lab, which has several California locations, shuttered its only Oregon lab. Announcing the closure on LinkedIn, Green Leaf founder and CEO Rowshan Reordan wrote: “It comes in response to sustained industry pressure to produce fraudulent test results, combined with a lack of regulatory oversight and enforcement in Oregon.”

Oklahoma is also working on reforms. Adria Berry, the executive director of the Oklahoma Medical Marijuana Authority, agreed that the lack of comprehensive state monitoring has created an opportunity for labs to cheat. But OMMA is only seven years old and had to set up a testing program from scratch, she said. Like every state that has legalized cannabis, Oklahoma has had to create its own way. “For the expectation for us to be able to snap our fingers and do it as quickly as people have expected,” she said, “it’s just not as realistic in government.”

Although they are a few months behind schedule, OMMA is set to soon being operating a state testing lab. According to chief science officer Lee Rhoades, the new lab has a goal of testing 400 so-called reserve samples per month — duplicate samples that labs are required to set aside — and then comparing the results with whatever the lab reported. The agency will also have labs test identical real-world samples obtained from growers and producers in order to evaluate accuracy and variability between labs. And, finally, OMMA plans to test around 500 products purchased from dispensaries annually — a large-scale, state-backed version of the off-the-shelf testing that Parker and her collaborators at Scissortail Laboratories and other testing companies have done for the last two years.

Of the 42 states that regulate marijuana, as of April 2025, only 16 have some form of state testing lab, or plan to open one in the next year.

“I’m anticipating a change in the landscape once we’re out there doing what we need to be doing,” said Rhoades, who thinks that many lab owners will welcome the stricter oversight.

But for many people advocating for safer marijuana in Oklahoma, the process is unnecessarily bureaucratic and slow. Recently, state legislators killed a proposal to expand the list of pesticides that labs must test for from 13 to 60. Ian Cameron, who sat on the committee that set thresholds for the initial list in 2019, said that he’s disappointed: “Nobody thought that it would sit kind of idle and on the books for as long as it has without having an update.”

However, first state labs need to get better at their job, said Cameron. “Until all labs in the state can correctly detect and quantify pesticides on the current list,” he said, “extending the existing pesticide list only lends to a false sense of security for patients.”

Frustrated by what he views as a lack of action by OMMA, Havard has done some low-cost testing for Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma and also plans to put out additional reports on tests of retail products. He doesn’t place much faith in the new state lab, or in the regulator’s ability to crack down on bad actors. “If they’re not doing it, somebody has to call it out in order to try to correct what’s happening in our industry,” he said.

Maryland’s experience shows how regulators can work effectively with the industry. Passing rates for yeast and molds were too good to be true, said Lori Dodson, a senior adviser to the Maryland Cannabis Administration. When regulators proposed requiring a more accurate testing method, she said, members of the industry pushed back, concerned that failure rates would skyrocket for those who were not willing to cheat. Regulators began to wonder if they had set an unreasonable standard for growers to meet — and if, by creating a more lenient standard, they would actually get more honest results from labs. “So, we did something crazy,” said Dodson: The agency not only mandated use of the more accurate test, but also temporarily set the limit for yeast and mold 10 times higher. At the same time, she said, they kept tabs on toxic molds — most species are not hazardous to humans — and any reports of adverse health events.

The more lenient standard did not appear to harm consumers. And even though the allowable level of total yeast and mold was so much higher, the rate of fails actually increased. Labs, it seemed, were willing to flag the more egregious offenders once they didn’t feel like everything was going to fail.

The higher failure rate could stem, at least in part, from the required change in testing methods, said Dodson. But, another reason, she said, is that while still protecting public safety, the higher threshold may have removed the incentive to cheat. “It gave the labs the opportunity to be honest.”

Since first discovering contaminants in marijuana two years ago, Summer Parker and Charles Hrabina have tested nearly 300 off-the-shelf products, including, in addition to marijuana, the papers, wraps, and cones used to smoke cannabis; low-THC products derived from hemp; and a few cigars. So far, according to Parker, their tests have identified 13 pesticides at levels that exceed state maximums, plus others that the state doesn’t currently regulate, and excess amounts of heavy metals arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury.

Summer regularly posts test results on the Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma Facebook page and the couple drop off reports on failing products at state legislators’ offices. About a dozen or more active members of their group continue to meet with policymakers, and Parker recently started hosting a podcast on WTHC radio, an internet station for medical marijuana users.

Two longtime cannabis activists, Ron “Reefer Ron” Welchel (left) and John “Old School” Frasure (right), attend the November meeting at the Oklahoma State Capitol. Both veterans, the men are also members of Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma. About a dozen or more active members of the group continue to meet with policymakers.

Visual: Teresa Carr for Undark

Over the last two years, the couple have devoted themselves full-time to their activism. To help cover their expenses, they say they’ve dipped into savings, and Hrabina has sold property as well as his 1969 Chevrolet Camaro.

One of the couple’s main goals is to make producers realize that they are not selling weed like back in the black-market days, said Parker. “We’re going into a licensed medical facility to purchase a medicinal product,” she said. “And until these growers and processors treat it like it’s medicine and not just a cash crop, I don’t think we’ll clean up all the problems.”

Like many experts, Arizona State University toxicologist Max Leung would like to see nationwide safety standards for cannabis, as well as funding for research to inform those regulations.

Leung co-authored a 2022 analysis showing that current regulations aren’t consistent — flower and extracts that would fail for contaminants in one state would pass in others — and don’t always make sense. The researchers found, for example, that about one-quarter of regulated contaminants are herbicides, even though “weed control was not known to be a key concern in cannabis production.”

Even with those gaps, Leung wrote in an email, regulated marijuana is far safer than illicit products that aren’t purchased through licensed dispensaries. In addition to lab testing, which does catch many problems, state regulations create standards for growth and production and require inspections at different points in the system. Still, he and others argue, people buying legal cannabis should be able to have the same expectations of consumer protection than they would for other goods. Leung is most concerned about people who use marijuana to address health concerns like cancer and Parkinson’s. With any other medication, patients can expect it meets strict standards, whether they buy it in Maine or California, said Leung. “But that’s not the case when it comes to cannabis.”

“What people like Summer and Charles are able to do is put a human face on things and helps us understand we need to expedite for the consumer, move as rapidly as we can to get where we need to be.”

Parker and Hrabina have “played a very big role” in calling attention to the problems with marijuana in Oklahoma and pushing for reform, said Rhoades, the OMMA chief science officer. In a January interview, he said he’s wanted to do the kind of testing they have been doing for a while, but until the state lab opens, he lacks the resources. “I was really kind of hoping that our laboratory could guide us to what’s really happening here in Oklahoma.”

“What people like Summer and Charles are able to do is put a human face on things and helps us understand we need to expedite for the consumer, move as rapidly as we can to get where we need to be,” said Rhoades.

Scissortail operations manager Sarah Cameron said that Patients for Safe Access of Oklahoma is having a positive effect on the industry. Recently, a client came into the lab who didn’t realize that Scissortail worked with the group, said Cameron. “He just brought it up and said, ‘There’s no point in doing it wrong now because Summer’s out here testing these products.’”

Paula Rowińska and Aleszu Bajak contributed reporting.

This story was supported in part by the

This story was supported in part by the