The Scientist Pot Farmer: On the Hunt for Safe Cannabis Agriculture

The smell feels illicit even though it’s not: a pleasant blend of pine, cedar, and skunk. It hangs in the air of a refurbished brick warehouse in downtown Spokane, permeating each drafty room. One of the only residents on this early January evening is ODO Oil, a company that processes cannabis oil, but there are big dreams of a sprawling cannabis business district with recreational shops and kitchens baking pot-infused treats. Upstairs, 60 rundown hotel rooms may eventually be converted to pot-friendly condos. For now, the main floor is mostly empty, save for a few televisions in the storefront windows broadcasting a CNN rerun about cannabis onto the snowy, empty streets outside.

I’m visiting ODO with Alan Schreiber, a scientist who plans to do business here. The company’s lab director, Steve Lee, is telling us about the history of the building, but Schreiber promptly interrupts. “I want to see my product. I just want to talk about what’s going on,” he says.

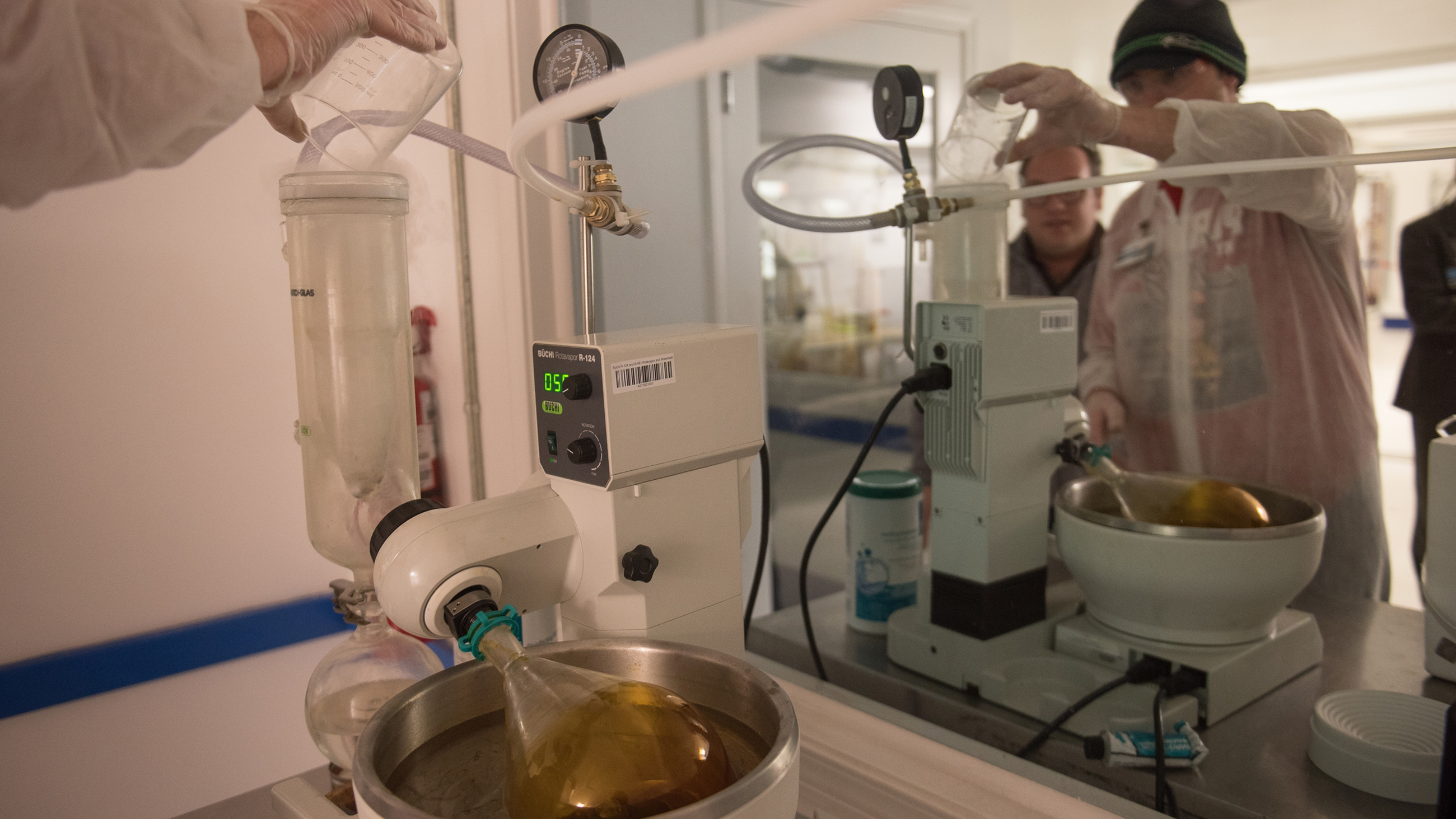

“Absolutely,” Lee says. He guides us downstairs to the main processing room. It’s loud and hot and filled with $1-million-worth of extraction machines, which wrest the oil from dried, ground cannabis plants. The extraction concentrates the compounds that give pot its oomph — dozens of chemicals called cannabinoids, which include tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the main psychoactive ingredient. A guy in Tyvek coveralls and protective gloves pulls a lever to spritz a first-run of raw oil into a clear plastic cup. If we’re being charitable, the oil looks like melting caramel gelato; if not, it’d easily be mistaken for the contents of a baby’s diaper.

We make our way to a secondary processing room, quieter and cooler, where the oil is filtered and spun until it has the deep viscous clarity of buckwheat honey. Lee holds up a Mason jar of the stuff, estimated at $18,000 wholesale. He explains that in order to land on store shelves as inhalable cartridges, or as an ingredient in cookies, candy or other edible goods, the oil must go through state-mandated safety and quality tests from a third-party lab to assure that it’s free of contaminants such as bacteria, mold, and remaining solvents. The labs also determine the potency.

Schreiber, a former academic entomologist and pesticide toxicologist who is now essentially a hired gun in agricultural pest control, then turns to me. “I’m going to make a statement, and he’s going to agree with it or not agree with it, or maybe counter it,” he says, nodding at Lee. “He doesn’t have to test that for pesticide residues.”

Lee agrees. “Currently in Washington State there is no mandate that we have to test for pesticides,” he says.

Like all agricultural products, cannabis attracts pests and disease, from spider mites to aphids to powdery mildew. But while growers in Washington — which voted to legalize the plant for recreational use in 2012 — consider cannabis a crop worth protecting from these destructive forces, the federal government, at least for now, still calls it a Schedule I drug — the same level as heroin and LSD, and technically more dangerous than cocaine, methamphetamine, and prescription painkillers. This week, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration suggested in a memo that it is considering whether or not to reschedule marijuana, although the agency has resisted doing so numerous times since the drug’s Schedule I classification was set in 1970.

Pesticides are also regulated at the federal level through a law called the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, which is administered by the Environmental Protection Agency. Among other things, pesticide companies must register their products with the EPA, and they must provide data — which may come from the company itself or from independent labs — that documents how well each product works, and whether there is any potential toxicity to people or the environment. Not everyone agrees that this safety data, or the EPA’s understanding of it, is sufficient, but the agency ostensibly considers all the evidence and decides whether the product should be allowed for sale and how it should be labeled.

That label you see on a can of Raid, for example, is a legally binding document explaining how and where it can be used. Organic pesticides, such as those derived from certain plants or bacteria, follow a similar path to registration, which is often quicker and requires less data compared to conventional pesticides.

Under normal circumstances, then, farmers who want to use pesticides on a crop simply look up which products are allowed on that crop for that particular pest. The USDA and state agencies may also require farmers to keep records of what they use, as well as when and how much.

But the EPA hasn’t approved any pesticides for cannabis. This has left Washington and other states with legalized cannabis in the awkward and unprecedented position of trying to provide pesticide guidance to its growers without breaking federal law.

So far the solutions have been piecemeal, and regulators are dealing with a veritable Wild West. Some growers are sneaking in illegal — and sometimes dangerous — pesticides at levels grossly exceeding what is allowed on other crops. While there’s no evidence of an effect on people’s health in Washington, industry experts say there is reason for concern — and the misuse poses a risk not only to cannabis consumers, but also to the workers applying the pesticides.

Earlier this year, Washington fined two growers and suspended cannabis licenses of two more for illegal pesticide use, though the state didn’t recall any products because the framework to do so had not yet been created. Pesticides may be safe at the right levels, but even Schreiber — who describes himself as very comfortable with these chemicals — finds the possibility of overuse “an unacceptable risk.” And no one knows for sure which pesticides would be best and safest to use on the plants because virtually no one has done the research.

This makes the distribution of cannabis oil particularly troubling. There is strong evidence to suggest that the extraction process concentrates not only cannabinoids, but also many pesticides. In 2014 in Oregon, researchers found residues of unapproved pesticides on products that were already on dispensary shelves, including cannabis extracts with levels of carbaryl, a pesticide approved for fruits and vegetables, at 415 parts per million (tolerance for blueberries is just three parts per million). In 2015, the Denver Department of Environmental Health, suspecting illegal pesticide use, quarantined 100,000 cannabis plants. Most of the plants were clean, but some had traces of pesticides including myclobutanil, a fungicide for powdery mildew.

Myclobutanil is approved for edible crops, but it’s not for smoking. When it’s exposed to fire — like the flicker of a lighter against a joint — it can break down into hydrogen cyanide, an agent used in chemical weapons.

On the other side of the room, a table holds around 40 more plastic cups of partially-refined cannabis oil. Somewhere in that collection is a sample that belongs to Schreiber — a test run from his latest research endeavor, a cannabis farm. He aims, among other things, to sort out the best pesticides for cannabis, and to help get them registered, which could mean less abuse and overuse.

Few scientists in the state are in the position to do this sort of work, but Schreiber, a consummate agricultural researcher who says he voted against cannabis legalization, seems uniquely suited to the task. But he’s also coming to recognize that this isn’t — at least not now — an ordinary crop. It’s one that is both badly in need of sound science, and one likely to make its earliest producers, and possibly Schreiber himself, very, very rich.

Lee reaches for two white buckets tucked in a corner, which collectively hold several gallons of additional raw oil. “Here, hold this with your hand,” he says to Schreiber. “Guaranteed, whatever thing you’ve wanted your whole life — if you could find a way to pawn that at close to wholesale value, you could have one. That’s like one of those cartoon bags of money with a dollar sign on it.”

Schreiber, whose gray hair is cropped military short and whose black-rimmed glasses are attached to a yellow neoprene strap that hangs down the back of his professorial tweed jacket, takes a bucket in each hand.

He looks up and asks: “Will you take a picture of me?”

Cannabis is nothing new in Washington. In 1998, a voter initiative on medical use gave patients a legal defense against prosecution, as long as they had a doctor’s note and kept no more than a 60-day supply. But that initiative had no regulatory framework, and so the industry existed in a swirl of gray and black markets with no oversight from the Washington Department of Health, the Washington Department of Agriculture, or any other agency that would normally oversee medicine or crops. From there, the industry continued to grow across the state’s expansive and lush landscape, particularly after the Obama Administration, in 2009, announced that the federal government wouldn’t go after medical cannabis.

The next year, Washington extended authorization rights to advanced registered nurse practitioners and naturopaths, who were bolder with their authorizations than doctors. In 2011, the state allowed cannabis patients to pool their resources into collective gardens, which expanded the murky market even more.

In 2012, Washington voters legalized recreational cannabis through Initiative 502, one of the first states to do so along with Colorado (today, four states and Washington DC have legal recreational and medical cannabis, while 19 more allow medical only). This time, the state planned to regulate the new market from the start, and eventually bring the gray medical market under essentially the same rules — a cautious and controversial process that is still underway. But because of the federal drug scheduling, the state had to figure out this system from scratch. Other countries with decriminalized cannabis — which differs from legalization in that it only does away with criminal penalties for having small amounts of the stuff, rather than making it fully legal to use and produce — such as Spain or the Netherlands, didn’t even provide a workable model because they don’t have large-scale commercial operations.

Regulatory responsibility for recreational cannabis fell to the Liquor Control Board, including managing business licenses and enforcing penalties. In July 2015, the name changed to the Liquor and Cannabis Board. (“We lost ‘control’,” jokes Randy Simmons, the board’s former deputy director.) The LCB has plenty of experience with this sort of regulation — it’s the same role it serves overseeing more than 16,000 state liquor licenses. The board also set up an intricate system to track cannabis as it moves from fields to processors to shops.

But the LCB has no experience monitoring production. For liquor and beer, that’s the responsibility of the federal government. The EPA decides which pesticides can be safely used on ingredients such as hops and barley, for example, while the US Department of Agriculture helps protect fields from invasive pests and certifies organic farming.

“The cannabis industry is new to us,” says Rick Garza, the current LCB director. “Things like pesticide use is new to us.”

Since I-502 went into effect in 2014, the LCB has licensed 1,191 cannabis companies, including growers, processors, and retailers. Hundreds more are pending. Out of the LCB’s 310 employees, about 41 are dedicated solely to the cannabis industry, but one-third work in the enforcement unit and can carry out inspections for liquor and cannabis alike. For cannabis, these inspections are limited to checking growers’ shelves for pesticide containers, though if there is a complaint they may test the plants for residues.

While the EPA doesn’t endorse any pesticide for cannabis, the Washington State Department of Agriculture cobbled together its own list of 320 products that technically, if not officially, may be used. For example, pesticides labeled for food crops grown under the same conditions as cannabis, but which don’t limit use to a specific crop. But the key ingredients in most of these products are low-risk, such as cinnamon oil or soap — relatively safe because of their low toxicity, but also relatively useless for the same reason. Growers won’t likely turn to low-risk products for bad infestations or outbreaks.

Meanwhile, the state tasked its department of health to make new rules for medical cannabis. The result was a list of 13 illegal pesticides that growers are most likely to abuse. By July 1, 2016 all medical-grade cannabis in the state will be regulated under I-502 and must pass mandatory residue tests for these 13 products (the tests will also check for two classes of common pesticides on the state’s approved list to be sure these are within allowable limits). Cannabis that passes the test can display a certification logo; cannabis that doesn’t will be destroyed.

So far, the LCB hasn’t set a date to extend these rules to the recreational market, which already accounts for an estimated 35 percent of the cannabis trade in Washington (medical makes up 37 percent; the rest is gray market). The LCB says it was afraid that expanding pesticide rules so soon would strangle the industry, because the tests are expensive and few labs in the state are able to perform them. “We decided to err on the side of caution and not add new regulatory burden on the recreational side,” says Jodi Davison, the supervisor for the LCB’s Marijuana Examiner Program.

The EPA declined repeated requests for an interview or to provide comment for this story, and the agency has been relatively quiet on cannabis in general. One exception is a May 2015 letter the agency wrote to the Colorado Department of Agriculture granting states with legalized cannabis permission to apply for a “special local needs” registration to allow an additional use of an already registered pesticide. Farmers with uncontrollable pests who have tried labeled pesticides to no avail can ask their state’s department of agriculture to identify potential alternatives and check whether the EPA has any concerns against that product.

In order to get approval, the state must prove there is a unique need for the pesticide and provide data showing that it’s safe to use on similar crops or in equivalent settings. The state may also generate more data to support their cause, such as showing the pesticide works against the specific pest for the intended crop. If the EPA decides this data is satisfactory, they may give the state permission to issue the registration to use the pesticide on this crop. This license is only valid in the state that applied for it, although other states with similar needs can piggyback on the original request.

State regulators cite the letter from the EPA as a significant step, but not everyone is thrilled. The watchdog nonprofit Beyond Pesticides, which supports the use of least-toxic pesticides when necessary, sent a letter to the Colorado Department of Agriculture in July 2015 saying that the state and the EPA will break federal law by issuing the registrations for cannabis. The organization is known to sue when regulators don’t heed its warnings.

There are other obstacles, too. These special licenses typically require cooperation both from the companies that own the chemicals and independent researchers who can test them, a role that often falls to agricultural departments at universities. Most universities, though, aren’t willing to work with cannabis because they’re afraid to risk their federal funding.

The state legislature did introduce a bill granting research licenses, which would allow collaboration among scientists at Washington State University and the University of Washington, although the governor recently vetoed it along with 26 other bills because of a budget crisis. It’s possible the research bill will come back, but even if it eventually passes, the schools might not participate. UW says it has no provisions for cannabis research other than very specific cases that were already approved by the federal government, although the policy may shift to match the “rapidly changing” legal landscape. And WSU, which does far more agricultural research, won’t get involved “until there is reconciliation of both federal and state law on the legality of this crop.”

While the government takes baby steps toward a solution and universities shy away from pot agriculture research altogether, Schreiber — a former EPA pesticide analyst and assistant professor at WSU, where he worked in an environmental quality lab for five years — wants to fill in the gaps. For the past 18 years, he has studied pesticides on small test plots on his 100-acre independent farm in southern Washington, conducting research for numerous big-name agricultural clients such as Bayer, DuPont, and Monsanto. He also does research for agricultural groups and smaller companies that make biological-based pesticides. He farms, too, and sells organic produce at local markets and Whole Foods. He also runs Washington’s blueberry and asparagus commissions — organizations that advocate for farmers and promote their crops — and he is the administrator for the state’s commission on pesticide registration.

Schreiber is now running pesticide safety workshops for pot farmers and he’s trying, controversially, to launch a cannabis commission to help further the interests of pot farmers. And on a separate plot of land, far from his test plots of blueberries and onions, he’s also growing cannabis.

“My whole life, I was groomed to be in this position,” he says. “I go into situations where sometimes the university or USDA has given up — they have pest problems they can’t solve. I get called in, then clean up and fix it.”

The morning after our visit to ODO Oil, a fog blankets the landscape as Schreiber’s red pickup weaves down Interstate 90 and then highway 395 from Spokane toward Pasco. We’ll make a brief stop at his primary farm before heading to the “cannabis campus,” the collective where Schreiber’s research and growing site for Paladin, the name he’s given to his cannabis research company, is located. The name comes from a group of legendary knights that served Charlemagne’s court, though Schreiber prefers a more modern reference: Paladin was also a free agent in the western TV series “Have Gun, Will Travel,” which first aired in 1957.

“His fast gun for hire heeds the calling wind,” the show’s theme song went. “A soldier of fortune is a man called Paladin.”

Schreiber had to keep the farms separate in part because his original operation is in Franklin County, which saw strong opposition among voters to legalization in the state. The county currently has a moratorium on growing or selling cannabis, and Schreiber makes clear on our drive that he voted against legalization of cannabis in Washington himself. He’s not adamantly against cannabis, he says, but it was never really his thing and his clients tend to have a conservative streak (he describes his own politics as “militant moderate”).

But I-502 passed anyway, and not long after, growers began calling him for pest-control advice.

He recalls one farmer who called him and asked how to control mites. When Schreiber asked for more details, like what crop the farmer was growing — key information for controlling the pests — the farmer balked before admitting he had a legal medical marijuana crop. “I said ‘What are you using,’ and he said ‘Imidacloprid’” — a neonicotinoid, an insecticide that is a synthetic version of nicotine and that the EPA recently confirmed is harmful to bees. “And I said ‘Imidacloprid? That doesn’t work on mites. Where’d you get that?’ And he says he was given it by someone in the industry, they sell it to him by the teaspoonful. He puts it on every morning and it’s not working.”

Many advocates tout pot as a miracle drug for ailments from multiple sclerosis to chronic pain to childhood seizures. The science isn’t settled on how well it works in every case, but the fact is that people who are already sick — sometimes very sick — use it as medicine. Unknown pesticide levels with unknown health effects are especially dicey for this vulnerable population, which is why the state health department plans to require testing on medical cannabis in July.

The farmer who called Schreiber about his mite problem uses his medical cannabis operation to treat family members, including a grandson who, according to the farmer, is a veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“That really shook me,” Schreiber says. “This gentleman has a crop that is legal for him to grow, he has a pest problem, and he’s using the wrong product. He is probably putting on more than he should. But nobody is available for that guy to turn to, to tell him the right thing to use, how to use it, when to use it. This guy has no one to turn to — all the traditional places he might go aren’t available to him.”

The farmer confirmed Schreiber’s account for me, but he asked that his name, along with the location of his indoor operation, be withheld for fear of reprisals from his anti-cannabis neighbors and the local government. Although his medical grow is currently legal, he will have to switch his license under I-502 by July 1 to comply with the new laws — but in a cannabis Catch-22, he is also in a county with a moratorium on I-502 grows. He had much to say about Schreiber. “He’s saving lives! That’s the man,” the farmer said. “That’s our hero.”

Along a narrow stretch of highway in south-central Washington, roughly 60 miles north of the Oregon border, we arrive at a towering privacy fence topped with video cameras and barbed wire. Schreiber punches a code into a keypad; a wide automatic gate opens and the truck crunches into a snow-covered parking lot. Schreiber parks by a golf cart and asks the woman who’s driving it if we can see his plot — one of several in a large commercial collective.

She hands us security badges, leads us to a locked gate, and swings it open. Inside is a snowy plot around half the size of a football field, with two locked storage sheds — one for cannabis and the other for surveillance equipment — and a pile of trash bags with thick, woody cannabis stems peeking out like bundles of kindling. The woman unlocks the cannabis shed. We sign our names on a state-mandated log and step in.

Inside are dozens of large black trash bags in stacks, some that reach over our heads. Schreiber unties one, revealing aromatic dried buds and leaves. He digs out a slip of paper printed with the variety (“Kush”), an identification number, and a QR code, part of the state’s tracking system. This is his first cannabis harvest, which he grew last summer — a pilot experiment to test the efficacy of various fertilizers.

Schreiber didn’t initially plan to sell the cannabis, but that was before he realized how much he could grow on his small plot, and how much the crop could be worth. This harvest came from just 7,000 square feet of the enclosure, and he estimates that the shed holds around 1,107 pounds of dried cannabis. The offers he’s received for selling it range from $450 to $800 a pound. “You know, I am not interested that much in being a grower,” he says, looking at the mountain of trash bags. “I want to do research on this.

“We had no idea that there was this much product in here,” he adds. “We were not prepared for what we were getting out of here.”

In a typical test on a conventional crop, a company will contract Schreiber about their desire to use an off-label or experimental pesticide — one the company and Schreiber both have permits to test, but isn’t available for sale. These pesticides have already been tested for human and environmental toxicity; Schreiber’s job is to see whether they work on the crop without damaging it. If the pesticide passes the tests, the company will petition the EPA to label it for the crop, and farmers will be able to use it legally.

Schreiber mimics how a farmer would use the pesticides, but in miniature: Rather than spraying 125 acres of potatoes, for example, he may use just a third of an acre, and he’ll use smaller versions of whatever application equipment a farmer would usually use. An experimental boom sprayer — a long wand attached to the back of a tractor that mists liquid pesticide through several nozzles — may stretch across a single row of crops rather than five, or a pivot sprayer that’s normally at least hundreds of feet long, may be shrunk to eleven feet. Or, Schreiber may walk through the test field with a backpack sprayer, squirting a pesticide on individual plants.

At a minimum, different sections of the test plot get a standard pesticide, the test pesticide, and a control. Various iterations of the experiment may include changes in the timing of the application, or pesticides diluted with varying amounts of water. The goal to see which treatment works best. If the pesticide is supposed to protect potatoes from aphids, for example, Schreiber will flip over a few leaves from each plant — leaves from the middle, rather than the older ones at the bottom or the younger ones at the top, as an aphid, like a tiny plant-sucking Goldilocks, prefers leaves that are just right — to count how many survived.

He’ll look for discoloration, to see if the pesticide interacted with sunlight to burn the leaves, and make sure the chemical did not curl, stunt or otherwise misshape them; check to be sure the potatoes aren’t larger or smaller than they should be; and measure the overall yield of the plot.

Following a similar protocol, Schreiber plans to start his first large-scale tests of cannabis pesticides this summer, but he faces a conundrum: Even when working with potatoes or blueberries, Schreiber’s test crops must be destroyed when his experiments are complete, because the pesticides aren’t yet registered for use on that crop and cannot be sold for human consumption.

This formula changes for cannabis, mostly because of the wildly different economics.

Legal sales of recreational cannabis in Washington State alone currently amount to $2.8 million every day, which continues to rise. In all of 2015, total sales were $260 million. That figure had already more than doubled from July 2015 to February of this year.

Schreiber was floored when he crunched the numbers coming out of his own enterprise. When he launched Paladin, he assumed most of his potential earnings would come from his expertise. “When I jumped into all of this, I had no idea the economic value,” he says. “I said, I’m not going to do production, I’m going to do research. You can make more money in research.”

Take potatoes, for example. According to Schreiber, the potatoes alone are worth $5,000 to $7,000 an acre. Research on that same plot is worth $20,000 to $25,000.

But an acre of cannabis is worth millions, and just how many plants Schreiber might need to get accurate data is unknown.

“For the cannabis plant, to the extent to which things are being applied very precisely, we would expect that you probably would be okay with a much smaller dimension,” says Angus Murphy, chair of the Department of Plant Science and Landscape Architecture at the University of Maryland, who has been contemplating how his group would handle similar research if asked by Maryland’s medical cannabis industry. “I don’t think we have the scientific evidence to say what that [dimension] would be, because it also has to do with the application method.”

For Schreiber, these uncertainties affect how he will conduct his pesticide tests. And he isn’t the only one struggling with the economic incentives: The value of cannabis is the very reason why some growers are tempted to use illegal pesticides. Even if a grower doesn’t want to go this route, the equation changes when an unexpected swarm of aphids or a bloom of mold attacks their crop — the motivation is to save it no matter what. To do otherwise would be like taking a blowtorch to mounds of hundred-dollar bills.

These economic pressures snake through the industry. Take, for example, the 14 third-party labs that the state has approved for cannabis testing — the labs that test plants and products like the oils from ODO in Spokane. Some labs may be cheating. Last year, a data scientist named James MacRae, who worked with the pharmaceutical industry for over 20 years and now does consulting for the state on cannabis, started crunching the public data from the labs. He found that some are far friendlier to the industry than others, declaring surprisingly high levels of THC potency, for example, or passing every single sample for mold, which MacRae says is extremely unlikely. Pot with high THC fetches a higher price on the market, while contaminated samples have to be destroyed.

The results have MacRae and others concerned. “As more people come into the market and begin using the products it has — if they’re using them thinking they’re safe, and they’re not, people will get hurt,” he says. “And people could die. It’s a little bombastic, but statistically that tends to happen when you’re willy-nilly selling mold-filled dope.”

The LCB knows about MacRae’s work, though it’s tight-lipped about the potential policy impact. “We’re aware of the tests and we’re aware of some of the concerns with the labs,” says Brian Smith, the LCB communications director. “We’re not saying at this point what we intend to do or are doing with the labs.” Even before MacRae went public, the board hired an outside lab called RJ Lee Group to oversee the cannabis-testing labs. But five of the six cannabis labs that responded to my interview request said that while RJ Lee did initially check their credentials, equipment, and protocols — and conducts annual inspections — no one regularly stops by to see the labs in action or to spot-check their work, nor are they legally required to do so. A representative from RJ Lee declined to comment for this story.

Although it’s possible that some of these labs won’t be able to afford the expensive equipment needed to test for pesticide residues, which cost from $250,000 to $500,000 new, it’s very likely that at least some will take on pesticide testing once its required on medical cannabis. The cheating may continue, too. “There absolutely will be [inconsistencies]. I can promise you that,” says Matt Haskin, CEO of the lab CannaSafe Analytics. “Laboratories that are doing poor work will be rewarded by the market. That’s the unfortunate situation that we have.”

The evening after we visit Schreiber’s farms, we make a long drive north to a Seattle suburb for the 2nd Annual Washington Cannabis Summit. The next morning, the meeting slowly comes to order in SeaTac’s Crowne Plaza top-floor ballroom. Forks scrape plates and glasses clink as participants, whose dress ranges from business attire to tie-dye, finish their breakfast. Although the tables are set for 250, the room is only about two-thirds full as attendees filter in and out. I overhear a tall man sporting a suit, cowboy boots, and a ponytail tell a friend that he’s taking a quick trip to the smoking area, a cannabis-friendly tent in the parking lot.

Last year, Schreiber spoke at the inaugural cannabis summit at this same hotel. His talk followed a keynote by Tommy Chong of the “Cheech and Chong” film comedies. Schreiber opened his talk by telling the crowd: “You aren’t my people. This is not my world.” To which someone in the audience shouted: “I’ll be your people!”

“It was unlike any conference I’ve ever been to,” Schreiber says. “People were just whooping and hollering at everything.”

This year seems no different. A young woman gives a speech. She’s a mother of three, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and, she says, a cannabis advocate. She grows her own in her backyard as medicine for her son, who has several behavioral problems as well as autism. “I helped that woman,” Schreiber leans over and tells me. “She was doing an amazing job, but she got russet mites.”

More panels come and go, with growers, lawyers, and the mayor of the only town in the country with a government-owned retail cannabis store. Two women give impassioned talks on hemp. “Those are the Hemp Sisters,” says Schreiber. There are more whoops and hollers.

At one point, a tall man wearing jeans and a thin silver hoop earring sneaks to our table and crouches by Schreiber’s seat to hand him a card. When the panel breaks, the two men hover in the corner of the ballroom, yelling over the din of the crowd.

The guy with the earring is Jeff Pinkham, global vice president for regulatory affairs for the soil, fertilizer and pest-control giant Scotts Miracle-Gro.

“So, you’re at Scott’s,” Schreiber says. “What do you want?”

“It’s simple,” Pinkham replies. “We want to bring safe, effective pesticides that the growers can use.”

It turns out that a new Scott’s subsidiary, General Hydroponics, plans to apply for one of the EPA’s special local needs licenses to market pesticides for cannabis. It’s perhaps the first major company that will do so.

“What do you have?” Schreiber asks, referring to the pesticides the company is considering that may be eligible for a special local needs application.

“Right now, we’re going to keep that sort of to ourselves, with apologies, because we don’t want anybody to get ahead of us,” Pinkham says. He later says that the company will only pursue registering organic pesticides for now.

The summit organizers get on the microphone to try to wrangle the crowd back to their seats for the next panel, while Schreiber tries to figure out what pesticides Pinkham’s company is considering for the special local needs registration.

Schreiber asks Pinkham if his company has access to pyrethrin, referring to a common organic pesticide derived from crushed chrysanthemums, and azadirachtin, which comes from neem tree seeds.

Pinkham sighs. “Forgive me, we just really, from a proprietary standpoint — once we submit I’ll call you up and tell you.”

The meeting wraps up in the early evening and the audience heads to the hotel lobby for a cocktail hour. Schreiber pops in and out of different circles, saying hello and shaking hands until the crowd funnels into another ballroom for dinner. The lights are low and a DJ spills ambient music over an empty dance floor. Schreiber sits at a back table near the buffet. As the seats fill up, he and an acquaintance argue whether the term “stoner” is pejorative. The acquaintance says yes. Schreiber is unsure.

A man takes a seat next to them. When he’s introduced to Schreiber, he says: “This is the guy I was bitching about!”

The table erupts in laughter. Apparently there is a dispute over whether Schreiber owes the man, the treasurer for a statewide cannabis organization, money for a pesticide safety workshop he underwrote. Pretty soon, Schreiber is telling the table funny stories about the accountant who does the books for Paladin – a biker who loves motorcycles and froufrou cocktails. He moves the conversation to taxes, indoor versus outdoor cannabis farms, and his research company.

The treasurer slaps his hand on the table and says: “I like you.”

Perhaps Schreiber is among his people after all.

Note: Steve Lee, the lab director for ODO Oil, left the firm after reporting for this story was completed.

The story has been updated to correctly identify the federal agency charged with drug scheduling. It is the Drug Enforcement Administration, not the Drug Enforcement Agency.

Brooke Borel is a New York-based science journalist and a contributing editor at Popular Science magazine. Her work has also appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, BuzzFeed News, Slate, and PBS’s NOVA Next, among other publications. She is a 2016 Cissy Patterson Fellow at the Alicia Patterson Foundation.